J.D. Salinger fled the Manhattan literary scene for a hillside cottage in Cornish, New Hampshire, and was more or less never heard from again. Howard Hughes spent many of his waning years holed up in the penthouse of Las Vegas’s Desert Inn, refusing public comment and shunning public appearances. Thomas Pynchon, America’s most successfully private artist since Emily Dickinson, has managed to go six decades without having so much as a clear picture taken of him. But in the era of social media and digital surveillance, such seclusion is increasingly difficult to maintain, so these days, anyone can go to YouTube and watch Terrence Malick dance.

In the video, Malick—the 73-year-old director of Badlands, The Thin Red Line, The Tree of Life, and the forthcoming Song to Song—is at the Broken Spoke in Austin, the city he has called home for most of his life. The San Antonio–based band Two Tons of Steel is playing at full locomotive tilt on the honky-tonk’s stage, and we watch as Malick—bearded, balding, and smiling softly—shuffles along in his best approximation of the two-step. Malick, who in high school was known as the Dancing Bear, more for his husky frame than his nimble feet, looks unaware that anyone is filming him. He is holding hands with his wife, Alexandra, who goes by Ecky, and together they slowly circle the dance floor. The video is mundane in nearly every way—twelve seconds of poorly lit, slightly jittery, low-resolution footage that shows an older couple dancing happily but unremarkably. But within a day of surfacing, in late 2012, the video, “Terrence Dances,” was reposted and written about by the Huffington Post, Vulture, Slate, and IndieWire. To date, it has been watched more than 33,000 times.

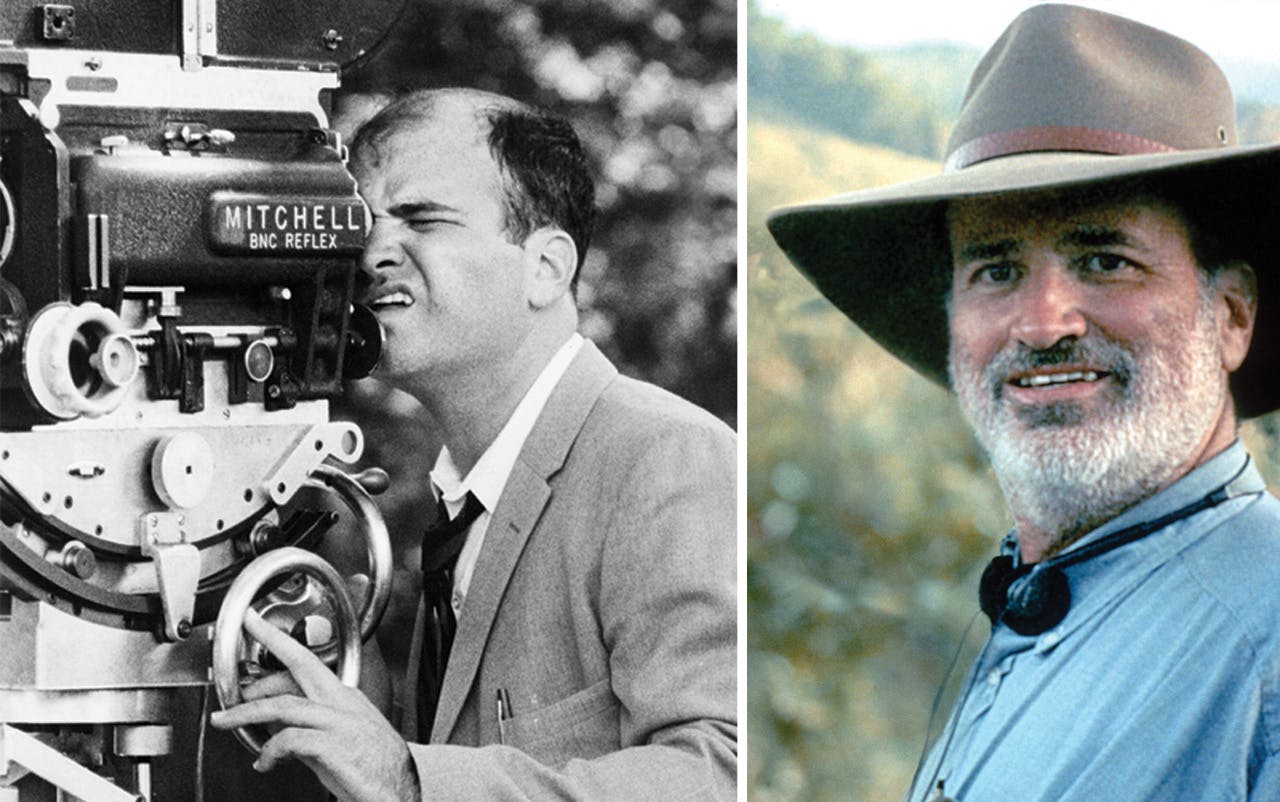

That a certain segment of the internet would be so hungry for even a fleeting glimpse of Malick is not surprising. The director is as famous for his closely guarded privacy as his output. He has not given an on-the-record interview in nearly four decades. From 1978, when Paramount released Malick’s second film, the Panhandle-set Days of Heaven, until 1998, when his World War II epic, The Thin Red Line, premiered, Malick more or less vanished. Rumors circulated around Hollywood that he was living in a garage, that he was teaching philosophy at the Sorbonne, that he was working as a hairdresser. Even as he returned to filmmaking, was nominated for Oscars, won the Cannes Film Festival’s Palm d’Or, and doubled down on his experimental style (cinephiles will never stop debating his decision to punctuate a fifties Texas family drama with CGI dinosaurs in The Tree of Life), Malick continued to maintain his silence.

In Austin, though, Malick has always been a little less enigmatic. “If you work at Vulcan Video, if you went to high school with him, then he’s Terry, he’s not this reclusive guy,” director Richard Linklater, who first met Malick almost 25 years ago, told me. Still, Linklater said, “there’s always a bit of mystery with Terry. He’s kind of everywhere and nowhere.”

Starting in September 2011, Malick seemed almost omnipresent around town, working on a new film that would be known for years only as Project V. At the city’s major outdoor music festivals—Austin City Limits and Fun Fun Fun Fest—Malick could be seen darting through the crowds, a camera crew in tow, movie stars such as Christian Bale walking briskly beside him. His crew popped up at a Texas-Baylor football game, engaging in a stealth shoot until the giant scoreboard monitor captured Natalie Portman in the crowd. The director himself was spotted on the balcony of the Violet Crown Cinema, laughing with Ryan Gosling and Cate Blanchett. At the Volstead Lounge, he drank tequila and ate tacos with his filmmaking team.

Fans armed with iPhones did not let these occurrences go undocumented. A man who has been so elusive that the gossip website TMZ dubbed him a Hollywood Bigfoot was now working consistently, almost predictably, in public. “Terry went from being one of the least-photographed directors in the world to what seemed like the most,” Malick’s longtime producer Sarah Green said. “But I honestly don’t think he thought about that too much. It was the only way this movie could be made.”

On March 10, Song to Song, the movie that Project V became, will have its world premiere at Austin’s Paramount Theatre as part of the South by Southwest Film Festival. (It will be released nationwide on March 17.) The film stars Gosling, Portman, Rooney Mara, and Michael Fassbender, and, according to the promotional materials, it is a “modern love story set against the Austin, Texas, music scene,” in which “two entangled couples chase success through a rock ‘n’ roll landscape of seduction and betrayal.”

That makes Song to Song sound far more conventional than it will almost certainly be, since Malick has increasingly distilled plot and dialogue down to their trace elements and assembled his collage-like films from captured moments of spontaneity—whether an uninhibited laugh from an actor, the intrusion of a butterfly into the frame, or a breeze rustling the leaves of an oak. Why Malick decided to make a film set in his adopted hometown, why he chose to document Austin’s music festivals, why he made a rock and roll movie after a career-long preference for Romantic-era classical composers and European church music, and what all of this means to him personally—these are questions that Malick will not answer.

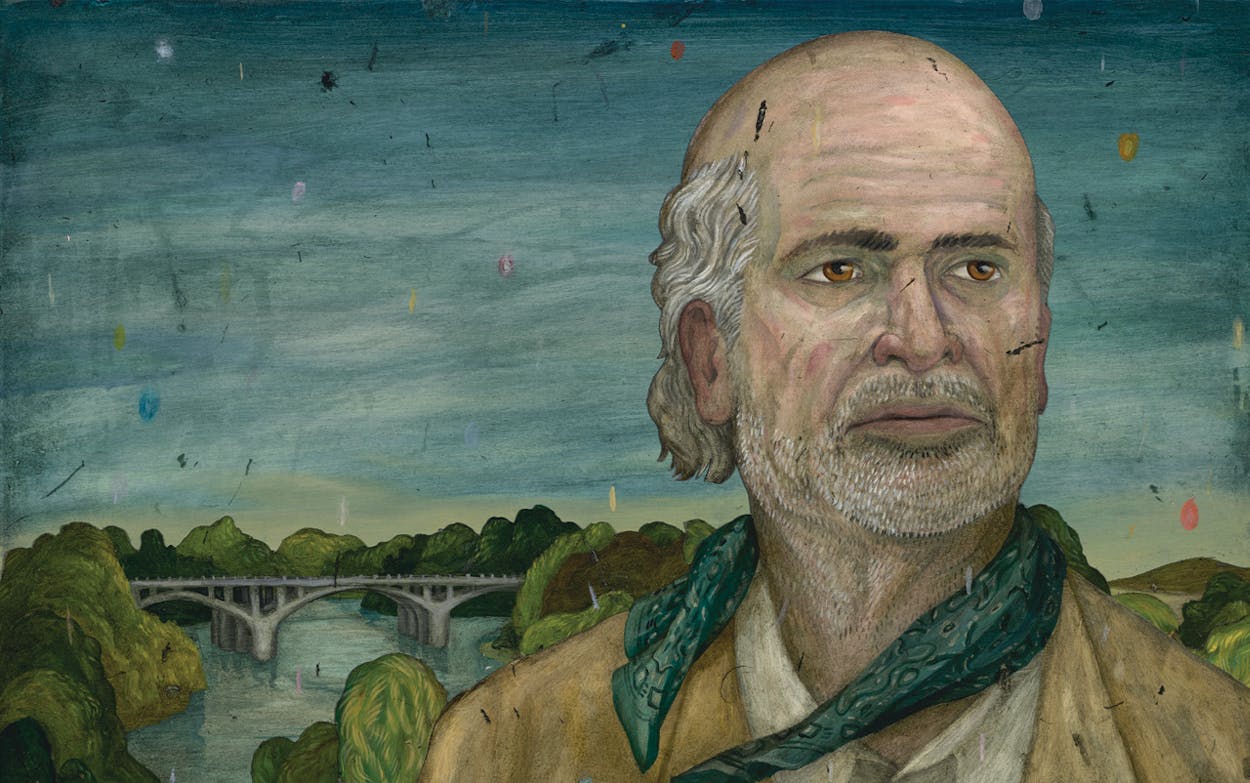

In his last published interview, in 1979, Malick gave a sense of how he saw his city back then. “It was in Austin that I had the idea for Days of Heaven,” he said to the Paris daily Le Monde. “I found myself alone for a summer in the town I had left as a high school student. There were those green, undulating hills, and this very beautiful river, the Colorado. The place is inspired and inspiring.”

St. Stephen’s Episcopal School, where Malick arrived as a boarding student in the late summer of 1955, sits on a 370-acre former goat ranch in the cedar-scrub-covered hills west of downtown. Back in those days, the school had a “frontier feeling,” remembered Jim Romberg, a high school friend of Malick’s. The road in was serpentine and remote, the surrounding area was undeveloped, and the school’s property teemed with natural diversity. Students would scamper down to the Gulch, where bald cypress and sycamore trees formed a towering canopy over a cascading brook, and attend chapel on the Balcones Escarpment in a building made from limestone quarried on campus. “Nature was all around us, and you felt a kind of isolation out there,” Romberg said. “Terry appreciated that.”

Malick was born in Illinois in 1943 and spent his boyhood mostly in Waco and Bartlesville, Oklahoma, the eldest of three brothers. His mother, Irene, was a homemaker who had grown up on a farm near Chicago; his father, Emil, was the son of Assyrian Christians from Urmia, in what is now modern-day Iran, and staked out a career as an executive with the Phillips Petroleum Company. Emil was aggressively accomplished, a multi-patent-holding geologist who played professional-level church organ and served as a choir director, and he pushed the young Malick to succeed on all fronts from an early age. (A Waco Tribune-Herald news brief from 1952 noted that “eight-year-old Terry” had “surprised his classmates at Lake Waco Elementary School by presenting a 43-page paper on planets.”) But Emil could be a stern taskmaster, and he and Malick often butted heads. “They had some conflicts over the years,” Jim Lynch, a close friend of Malick’s since high school, told me. “That’s one reason Terry came to St. Stephen’s.”

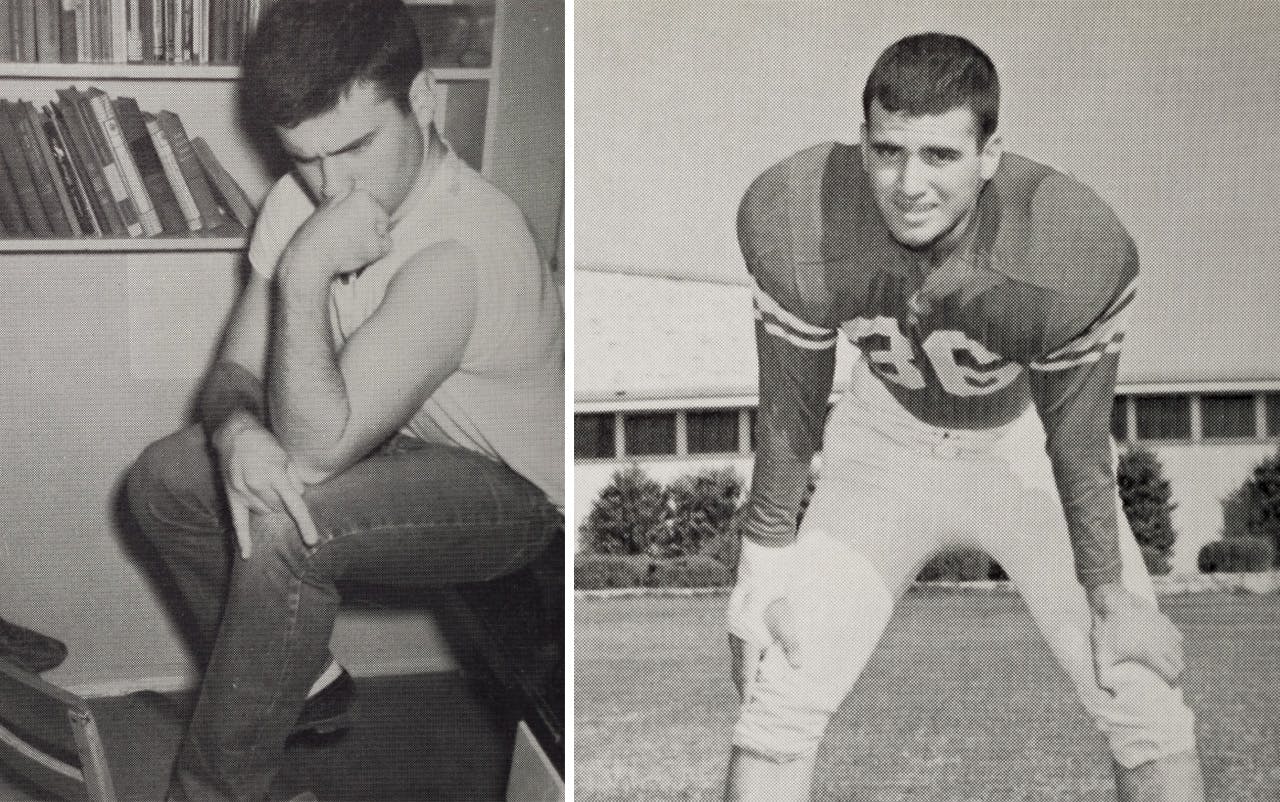

St. Stephen’s is known as the Hill, both for its steep topography and its aspiration to be an enlightened beacon (as in the biblical “city on a hill”), and Malick thrived in a culture that emphasized spirituality, intellectualism, and rugged individualism. “When I first got there, it was made known that he was the local genius,” Lynch told me. Malick had the highest standing in the class his junior and senior years, served in student leadership positions like dorm council, played forward on the basketball team, and, with Romberg, co-captained the football team, playing both offensive and defensive tackle, an accomplishment of which he’s still proud. (“He says that in football he was ‘the sixty-minute man,’ ” Linklater told me. “Ecky says that the only time he boasts is when he talks about his high school athletic prowess.”)

None of Malick’s peers—or, it would seem, Malick—had any inkling that he would stake out a career as a filmmaker, but he was already exploring many of the ideas that would animate his work. Students at St. Stephen’s went to chapel twice a day, and the spiritual education there was both rigorous and open-minded, with The Catcher in the Rye taught alongside more traditional religious texts in the school’s Christian ethics class. “It was religious in a broad humanities sense,” Lynch said, a conception that Malick embraced. “Terry doesn’t like anything sectarian or dogmatic,” Lynch added. “His grounding is more in a philosophical sense of wonder.”

Malick was also immersed in the arts. He was an active member of the drama club. He and Lynch would listen to classical music recordings in the dorm, then challenge each other to identify compositions from a few notes of a whistled melody. (Malick had a special affinity for Modest Mussorgsky’s Pictures at an Exhibition and Camille Saint-Saëns’s Carnival of the Animals.) Malick participated in off-campus outings led by an English teacher named Bob Pickett to see foreign films by the likes of Ingmar Bergman and François Truffaut at the University of Texas or at the old Varsity Theater, on the corner of Guadalupe and West Twenty-fourth streets. “We would go to Pickett’s apartment afterward and talk about the significance,” Romberg said. “Terry was very involved in that.”

But for all Malick’s top-flight achievement and immersion in high art, he was also one of the guys. He played bridge with the older students after dinner, pulled pranks—Romberg remembers conspiring with Malick to trap armadillos and put them in other students’ rooms—and poked fun at his own “local genius” reputation. On his senior yearbook page, the future director strikes the seated pose of Auguste Rodin’s sculpture The Thinker, his chin resting pensively on his left hand. His right hand, lying against his knee, is surreptitiously giving the sign of the horns.

Malick’s path from St. Stephen’s to his emergence as one of the most talked-about directors in seventies Hollywood was a rapid ascent, but it had the qualities of a meandering quest for adventure. Upon graduation, Malick and a high school classmate decided that they’d spend their summer harvesting wheat in North Texas, where the prep-school boys worked alongside hardened seasonal laborers who, Malick would later say, “lived on the margins of crime, fed by elusive hopes.” The next summer, Malick, now a philosophy student at Harvard University, lived with Lynch and his family in Midland and got a job digging the foundation of a skyscraper downtown, operating a jackhammer and regaling his hosts with stories of the tough construction workers he met at the site.

After Harvard and a Rhodes Scholarship at Oxford University, Malick began experimenting with more-white-collar careers. He worked for a short time as a globe-trotting magazine journalist, interviewing Haitian dictator “Papa Doc” Duvalier and spending four months in Bolivia reporting for the New Yorker on the trial of the French philosopher Régis Debray, who had been accused of supporting Che Guevara and his Marxist revolutionary forces. (Malick never completed the piece.) Then there was a year as a philosophy lecturer at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, during which Malick concluded that he “didn’t have the sort of edge” required to be a good teacher. And finally, he moved to Hollywood, where he studied at the American Film Institute and quickly became an in-demand screenwriter, working on an early version of Dirty Harry, writing the script for the forgotten Paul Newman–Lee Marvin western Pocket Money, and making powerful friends like Bonnie and Clyde director Arthur Penn and AFI founder George Stevens Jr.

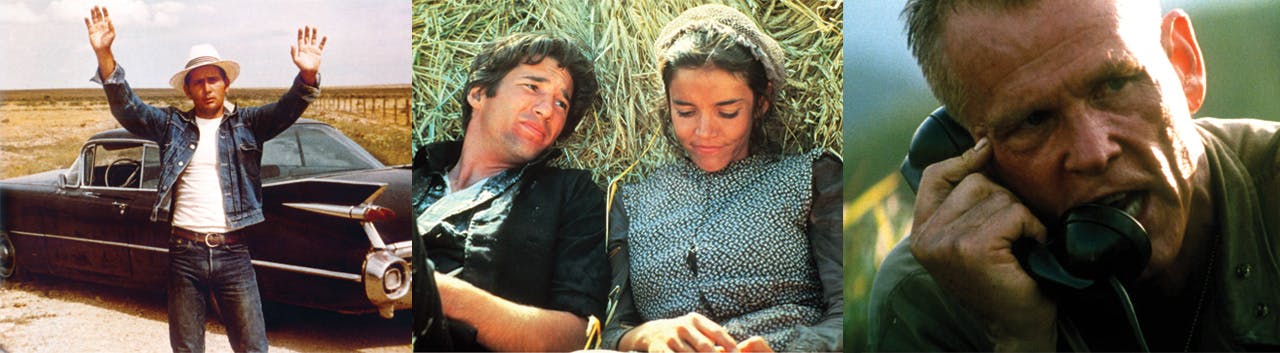

But Malick wanted to make his own film, and he found a story he wanted to tell in the late-fifties murder spree of Charles Starkweather. Though Malick had never directed a feature, he insisted on total freedom and had few qualms about scrapping the production schedule when he became inspired to shoot a different scene or location, exasperating many in the crew. But when Badlands, starring Martin Sheen and Sissy Spacek, opened at the New York Film Festival in 1973, Malick became an instant sensation. The New York Times critic Vincent Canby called it a “cool, sometimes brilliant, always ferociously American film” and wrote that the 29-year-old Malick had “immense talent.” (The Times also reported that getting Malick to talk about Badlands was “about as easy as getting Garbo to gab.”)

Soon, Malick began production on his follow-up, Days of Heaven, a tragic love story starring Richard Gere, Sam Shepard, and Brooke Adams set in the North Texas wheat fields where Malick had worked after high school. Badlands hadn’t been an easy shoot, but on Days of Heaven, Malick’s unorthodox approach had the crew on the brink of mutiny, and when the film finally came out, in 1978, the reviews were decidedly mixed, sometimes within the same review. “It is full of elegant and striking photography; and it is an intolerably artsy, artificial film,” wrote Harold C. Schonberg in the New York Times.

Days of Heaven won an Academy Award for best cinematography, and it is now widely regarded as a masterpiece. (Roger Ebert, delighting in the stunning magic-hour photography and the poetic tone, would judge it “one of the most beautiful films ever made.”) But the experience of making the film had been so grueling for Malick that, according to Badlands producer Ed Pressman, “he just didn’t want to direct anymore.” The year after Days of Heaven premiered, Malick abandoned production on his next project, a wildly ambitious movie called Qasida that he’d hoped would tell the story of the evolution of Earth and the cosmos, and informed friends and colleagues that he was relocating full-time to Paris.

In the final shot of Days of Heaven, two teenage girls walk down a railroad track, ambling toward an uncertain future. The “Aquarium” movement of Saint-Saëns’s Carnival of the Animals, the composition Malick loved as a student at St. Stephen’s, has been swelling in the background. One of the girls, the film’s streetwise narrator, begins to speak in a voice-over. “This girl, she didn’t know where she was going or what she was going to do,” the narrator says. “Maybe she’d meet up with a character. I was hoping things would work out for her.”

There is only one publicly available recording of Malick’s voice. Around halfway through Badlands, he makes the single on-screen cameo of his career, engaging in a brief, tense exchange with Kit Carruthers, the Charles Starkweather–like killer played by Martin Sheen. Malick speaks in a slow, soft, higher-pitched drawl. He is unfailingly polite, a little retiring, and warm without being chummy. Malick has one of those voices that lends itself to imitation—broad and regional and distinctive—and when I spoke with his friends and colleagues, I heard several versions of it. They all sounded like the Malick we see in Badlands.

Malick’s friends describe him as a generous and humble man with a capacious intellect and a child’s insatiable curiosity. He likes going deep on birding, cosmological events, and the interconnectedness of the natural world. (“You’ll be talking to him about butterflies in the Barton Creek watershed, and then he’ll start talking about the soil and all the soil insects,” said filmmaker Laura Dunn.) He enjoys discussing the fundamental questions that drive religious and philosophical inquiry and has a deep knowledge of the Bible. (Lynch remembers that after seeing Mel Gibson’s The Passion of the Christ, Malick—a fluent French speaker, with conversational German and Spanish—mentioned that he understood the film’s spoken Aramaic, because he’d grown up hearing it from his paternal grandparents.) And yet, as in high school, Malick can be just as down-to-earth as high-minded. He’ll show up for lunch at an unfussy cafe wearing a bright Hawaiian shirt and talk about football or gush about pop-culture schlock like the genetically-modified-shark movie Deep Blue Sea or drop a quote from Ben Stiller’s Zoolander. (After hearing that Malick was a fan, Stiller made an in-character happy-birthday video for the director.)

“He’ll make these wild associations that really surprise me,” said Ed Pressman’s son, Sam, a director and producer who fondly remembers Thanksgiving dinners with Malick at the property Ecky once owned on Lake Austin. “You’ll hear him say something like, ‘I just heard this Jason Derulo song, “Talk Dirty.” I haven’t heard a love song like this before.’ And you’ll think to yourself, ‘That’s so weird, that’s such a shitty pop song.’ And then you’ll listen to it again and you’ll hear this Turkish lick, and you’ll say, ‘Actually, that seemingly innocuous pop song has something really cool to it.’ ”

Malick has always been more reticent about self-disclosure. Lynch told me he only learned about Malick’s divorce from his first wife, Jill Jakes, when he called Malick’s house after a short period in which they hadn’t spoken. Jakes picked up the phone and, when Lynch asked for Malick, she said, “That marriage didn’t work out.” Corresponding with Malick during the director’s time in Paris, Lynch puzzled over whether the “Michèle” that Malick kept referring to in his letters was a woman with whom Malick was romantically involved or a male friend, since Lynch thought the name could be either female or male and Malick had failed to give any context. (Michèle turned out to be Michèle Morette, who would become Malick’s second wife.)

Malick is even more buttoned-up about his work. He politely shrugs off compliments about his films—which, in the old Hollywood style, he calls “pictures”—seemingly agonizing over flaws, missed opportunities, and bad memories of the production. “I’ll mention something like, ‘Hey, I heard there were some seventy-millimeter prints of Days of Heaven. And he’ll say, ‘Oh, gosh, when that opened, I was out of the country,’ ” Linklater said. “I think talking about his work takes him back emotionally.”

Laura Dunn, whom Malick recruited to direct The Unforeseen, a documentary about Austin’s development boom and the pollution of Barton Springs, told me that Malick finds it difficult to watch movies from start to finish. “He’s the kind of artist who seems almost tormented by his need to keep working on something,” she said. “If he’s sitting in a dark room, watching a movie all the way through, he’s restless because he’ll still be editing one of his own movies, or he’ll think about all the things he did that he regrets and wants to go back and change.”

Malick’s self-imposed exile in Paris was, in fact, not long. By the early eighties, he and Morette were splitting their time between the French capital and Austin (the couple married in Williamson County in July 1985), and Malick began to appear on the growing Central Texas film scene. Linklater remembers first seeing Malick in November 1987, when the older director showed up at Austin’s Laguna Gloria art museum for a screening that Linklater had organized of Robert Bresson’s Au Hasard Balthazar, a film inspired by Fyodor Dostoevsky’s The Idiot that explores the seven deadly sins. “He hadn’t been gone from cinema that long, so it wasn’t like what it became,” Linklater said. “It was more like Terrence Malick’s here!”

By the early nineties, Malick was looking to engage with the local film community in a more active way, and he began to recruit young, unproven talents to take on major projects—even if they’d never harbored such ambitions themselves. In 1993, Malick started playing in a weekly faculty pickup basketball game at St. Stephen’s, and he struck up a friendship with an English teacher named Joe Conway, bonding over their shared admiration for the Southern gothic stories of Flannery O’Connor. After attending a one-act play that Conway had written for St. Stephen’s students, Malick approached the teacher and encouraged him to consider tackling a screenplay. Malick and Ed Pressman had recently formed a production company, and Conway remembers they were looking for “brand-new screenwriters who hadn’t been corrupted by Hollywood.”

Malick supplied the source material: a transcript of a boy calling in to a runaway hotline with stories about his abusive father and the younger brother he had left behind at home. (Malick had been the volunteer who’d fielded the call, Conway told me. “It was an experience that really touched him. It’s got to be heartbreaking to sit there in the middle of the night listening to these kids.”) After years in development, Conway’s screenplay became Undertow, a 2004 film produced by Malick and Pressman and directed by David Gordon Green.

Not long after meeting Conway, Malick reached out to James Magnuson, the director of UT’s Michener Center for Writers, with an idea to enlist students in writing Texas-set screenplays based on works of classic literature. The project inaugurated a period in which, UT film professor Tom Schatz told me, Malick was “in his own kind of low-key, below-the-radar way, very supportive of the Michener Center and the writing programs at RTF,” the university’s radio-television-film college. Two of the Michener Center scripts, The Marfa Lights and Red Wing, both written by Kathleen Orillion and based on novellas by the French writer George Sand, ended up going into development, and Malick worked to shepherd them both to the screen. (The Marfa Lights was never made, but Malick’s stepson Will Wallace ended up directing Red Wing in 2013.)

Malick also looked to young Austin filmmakers to capture the shifting landscape of their city. Dunn had just gotten her master’s degree in fine arts from UT when Malick approached her, in late 2002, to see if she’d be interested in making The Unforeseen. Malick urged Dunn to go beyond a journalistic account of the more-than-decade-long fight between developers and environmental activists over Barton Springs. “Terry would talk about the springs as a kind of reflecting pool of changes in Austin,” Dunn said. “I think he was alarmed. There was a sense that something was at stake. He told me to take Barton Springs as that which God gave us and look at what we were doing to it.” Dunn’s finished film offers an elegiac look at Austin as a clear-streamed, laid-back, sadly fallen Eden, with tower cranes rising, the water growing murkier, and the poet Wendell Berry intoning, “What had been foreseen was the coming of the stranger with money. All that had been before had been destroyed.”

By this time Malick was deepening his own roots in the city. He and Morette split in the mid-nineties, and not long after, Malick reconnected with his eventual third wife, Ecky, a St. Stephen’s alumna from Beaumont with whom he’d been friendly in high school. (“Ecky was bright, incredibly energetic, and very popular,” Romberg remembered.) A few years after marrying, Malick and Ecky bought a home in West Lake Hills, a fifteen-minute drive from the front gate of St. Stephen’s, and the significance of the purchase was not lost on them. As Lynch told me: “Ecky likes to comment that she and Terry are like a couple of homing pigeons.”

Auditorium Shores, on the edge of Lady Bird Lake, lies ten miles downriver from Malick’s high school alma mater, in full view of the glass-and-steel high-rises glistening downtown, not one of which was standing when Malick first arrived in Austin six decades ago. And in a smartphone video shot on those lakeside grounds by a YouTube user in late 2012, we can see Malick working.

When the footage begins, he’s offscreen, likely standing in the wings of a temporary stage erected for Fun Fun Fun Fest, watching as Val Kilmer, at a microphone, in front of several thousand people, unleashes a chaotic performance. The Atlanta punk-rock band the Black Lips is assembled around Kilmer, but the actor pays them little heed as he announces, “Rock and roll is dead!” The three-time Oscar-winning cinematographer Emmanuel Lubezki, who has worked on Malick’s past five features, holds a camera and pushes in close to Kilmer’s face. Shouts of “F— you, Val Kilmer!” break out among the crowd, who came to see the Black Lips play music. Rooney Mara, holding a guitar, looks confused. Soon, Kilmer will appear to slice into an amplifier with a chain saw and will saw off clumps of his hair with a massive knife. But before the madness kicks into high gear, we see Malick duck into the frame. He’s there in front of us for two seconds, offering a few words to someone. And then he retreats.

When Malick began shooting Song to Song, Austinites weren’t quite sure what to think. “Over the summer of 2012, all my friends could talk about was how Malick was making a new film,” Peyton Stackhouse, a then-Austin-based actress who worked on Song to Song, told me. “You would hear people asking, ‘Why is he shooting a movie again? Didn’t he just shoot a movie?’ ” A prolific Malick seemed almost an oxymoron.

The public shoots at Auditorium Shores and neighboring Zilker Park were, in fact, just a small part of what Malick was capturing around the city. Patti Smith dropped by one of Malick’s sets, playing herself in a small role. Malick filmed a scene with Benicio del Toro that he’d originally conceived for the actor to perform in a Che Guevara biopic. At a mansion overlooking the Colorado River, Malick staged a nighttime party scene that sounds as Dionysian as Malick’s famous shots of swaying trees and shimmering tidal flats are biblically inspired. “There were thirty scantily-clad partygoers, ravers with these beautiful fluorescent batons, an infinity pool, and two big Afro-Cuban brothers pounding out salsa-ish beats on giant drums,” the actor Clifton Collins Jr., who has had roles in Malick’s past two films, told me. “Michael Fassbender is there dancing with Benicio. Natalie Portman is sashaying by herself. It was so easy for all of us to fall into the rhythms of what was going on, and that spirit was created by Terry.”

Austin-based luminaries dropped by—either to make a cameo or just to hang. When St. Stephen’s teacher and screenwriter Conway visited the Song to Song set, he found himself blown away by Fassbender’s manic, gonzo intensity, and remarked on it to Malick. “You want to talk wild,” Malick told him, “then you should have seen Robert Plant when he was out here yesterday.”

Whether any of this will accurately capture the Austin music scene as it exists in 2017 is a question moviegoers will have to answer for themselves. Most of the musicians credited in the film are not from Austin, and many people who watched Malick and his cast and crew shoot at the city’s major music festivals aren’t from here either. (A cynic would say that these facts accurately capture the Austin music scene in 2017.) Sarah Green, the producer, told me that Malick attended festivals like Austin City Limits as a fan before he filmed them. But if the city’s most famous “recluse” were routinely dropping by the Mohawk and the Continental Club, one might expect YouTube to be full of many more twelve-second videos, with titles like “Terrence watches a set” and “Terrence gets a beer at the bar.”

Malick takes years to finish his films, hiring teams of editors to put together different cuts, and finding and discarding entire story lines during the post-production process. In the final cut of The Tree of Life, Malick resolves the drama at the center of the film by having his young protagonist’s family move away from his boyhood home. There’s a bittersweet sense of a chapter closing and an uncertain future lying ahead. But in an earlier, unreleased version of the film, the story of the protagonist, Jack, ends not with his family’s departure from Waco but on a more triumphant note: he arrives as a boarding student at St. Stephen’s. It doesn’t take a deep familiarity with Malick’s life story to see the parallels between the family in the film and Malick’s own. Jack bridles under the discipline of his stern, accomplished, and ultimately loving father. He worships his angelic mother. He and his two younger brothers turn to each other for support. The film is framed around the premature death of the middle brother. (Malick’s brother Larry took his own life as a young man.)

In the unused ending, Jack leaves behind his tumultuous relationship with his father and finds a new kind of family. We see him walk past St. Stephen’s limestone chapel, the highest point on campus, those “green, undulating hills” standing in the background. “Jack is just enraptured,” said Conway, who has seen the cut. “He’s having this intellectual and spiritual awakening. If you take Jack as in any way reflecting Terry, well, St. Stephen’s is where he found a community that he embraced and that embraced him.”

Malick’s silence has always seemed, in part, a way to resist such a reading. When Lynch mentioned to Malick that he saw the director’s last three features—The Tree of Life, To the Wonder, and Knight of Cups—as an “autobiographical trilogy,” Malick took umbrage. “He didn’t like me labeling them that way,” Lynch said. “He didn’t want people thinking that he was just making movies about himself. He was making movies about broader issues.” Malick might very well say the same of Song to Song, but nevertheless, it’s tempting to see his latest work as an extension of that discarded Tree of Life ending—the aging director offering a raucous love letter to the city that offered him inspiration as a boy and has sustained him ever since.

- More About:

- Film & TV

- Longreads

- Terrence Malick

- Austin