On November 25, 1848, a young, illiterate slave claiming to be free walked into a Houston courthouse to sue the man who owned her. The woman’s odds, it would have seemed, were not good.

The new state of Texas allowed slavery, and one in four households in Houston owned African Americans. The judge in the case was a slave owner, as was the foreman of the jury. Even the woman’s Houston lawyer came from a slave-owning family in Virginia and would, when Texas seceded from the Union twelve years later, serve in the Confederate House of Representatives.

She was 26 years old, five feet five and 130 pounds, “a good looking, sprightly girl,” as one witness put it, with freckles and light-colored skin—“yellow,” in the parlance of the day. As she sat in that small courtroom and looked around at the men—the one who owned her, the one trying to free her, the twelve on the jury about to judge her—she probably thought about a lot of things. Her two young sons, for example, who would surely be separated from her and sold if she lost. She doubtless reflected on her mother, who, last she knew, was somewhere outside Nashville. She might have recalled her long, hard journey from Tennessee to Louisiana to Texas.

But one notion certainly never entered her mind, and that was the idea that, 168 years later, in her great-great-great-great-great-great-grandchildren’s time, not far from the spot where she now sat, this same city would turn her life, which had all the elements of classic human drama—love, death, bondage, the ache to be free—into a stirring work of words and music, an opera, named after her, Emeline, a slave desperate to be free. But that is exactly what happened.

In March 2003 Mark Davidson went searching for a good story. Davidson, a history buff, had been elected judge of the Eleventh District Court of Harris County more than a decade earlier, and in 1995 the president of the Houston Bar Association asked him to write some articles on local legal history for the Houston Lawyer. Davidson agreed and went to one of the six warehouses where county court documents were stored, a building in the Fifth Ward with no air-conditioning but abundant rats and roaches. He opened one of the hundreds of boxes, but when he lifted out the files, they crumpled into confetti. Davidson realized these documents were the last frontier of Texas history, so he went to the district clerk, Charles Bacarisse, and suggested they come up with a way to preserve them. Bacarisse, himself a history buff, agreed. They eventually gathered all the materials in one place, the five floors of the old downtown jail.

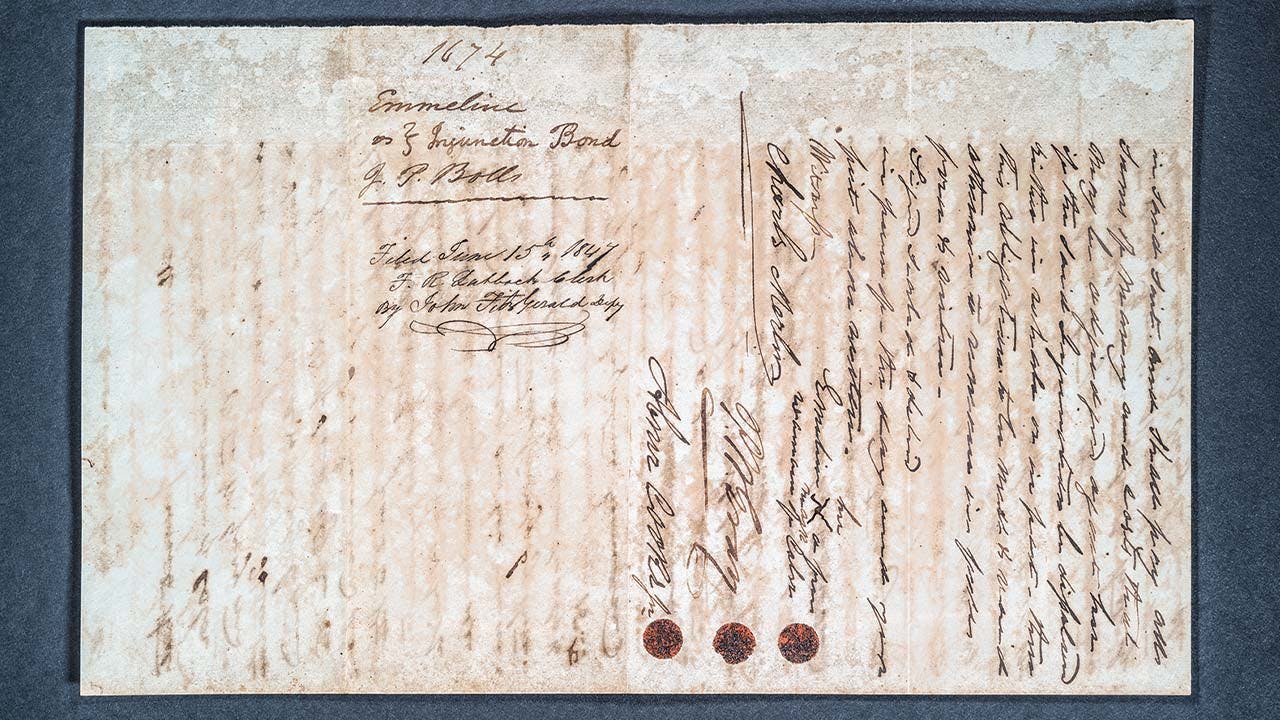

Eight years later, Davidson was exploring the archive and pulled out the biggest file he saw. The paper was brown and had plenty of holes and torn edges, but most of it was intact. The case was titled Emeline, a free woman of color v. Jesse P. Bolls. Davidson began reading the ornate, flowing handwriting and saw that Emeline’s attorney had been Peter Gray, the founder of Houston’s Baker Botts, one of the oldest law firms in the state. Davidson noticed the X the plaintiff had used to sign her name. The case file was full of petitions and interrogatories that themselves held facts about the lives of Emeline, her mother, and their owners in three different states. Davidson turned to the verdict and was stunned by what he saw.

Emeline’s story, like that of many slaves, begins with a concupiscent plantation owner. In 1811 or 1812, some ten years before Emeline was born, a young Louisiana planter named Donelson Caffery began fornicating with her mother, Rhoda. Caffery, in his mid-twenties, was from Nashville, which was co-founded by his grandfather. Caffery’s aunt married Andrew Jackson. In 1808 Caffery left Nashville and went south to the newly opened territory that would soon become the state of Louisiana and bought a plantation in the south-central part of the state on Bayou Teche; he also became a partner in a sugar plantation in nearby Attakapas with a Philadelphia merchant named Washington Jackson.

Jackson was Rhoda’s owner and a man who would eventually control a variety of interests, including a trading company in New Orleans and a schooner to ship his goods. Jackson and Caffery were part of an unofficial club of area planters that included John Murphy, from North Carolina, and Thomas Martin, from Nashville, who bought land next to Jackson and Caffery’s and soon became friends with them. They were all excited about their prospects. “There is no business in this country like farming,” Caffery wrote to his uncle Andrew Jackson in 1810. “An industrious man with a few negroes may soon make a fortune.”

In 1816 Caffery announced his engagement to Murphy’s daughter, Lydia. But he had a problem: he had fathered three children with Rhoda—George, Margaret, and Matilda—all of whom, Caffery’s partner said, looked a lot like their father. Caffery went to his friend for help. “He became anxious to do something for them,” Jackson later testified, “and direct their removal to a free state with a view to their becoming free.” Jackson offered to take them to Philadelphia, where, by Pennsylvania law, they would be emancipated after having lived there for six months. Caffery paid Jackson $1,000 for Rhoda and their three children, and the merchant took the four to New Orleans and then on a ship to the “Cradle of Liberty.”

Caffery reckoned Rhoda could find work as a laundress in Philadelphia, and for a time she worked for Jackson’s sister. But she couldn’t get enough steady employment to take care of her family, so Caffery arranged for her and the kids to be sent to the plantation of his friend Martin, near Nashville. Rhoda was to be a servant, not a slave, Jackson later said, and when the children were old enough, they were to learn trades, an arrangement Martin was in full agreement with: “Thomas Martin was an intimate and confidential friend of Caffery.” By 1817 Rhoda and her children—who Jackson said had spent more than six months in Philadelphia—were living on the Martin plantation called Locust Grove.

In the spring of 1822, Rhoda gave birth to Emeline, whose father was, in all likelihood, a white man. She later gave birth to daughters Lucy and Julia. The Martins were members of the Tennessee aristocracy, and Rhoda and her children would have seen many members of the upper class come through Locust Grove, including one man who would change the course of Texas history and possibly Emeline’s as well: Sam Houston. On a snowy January night in 1829, Houston, then the governor of Tennessee, arrived with his new bride, Eliza Allen, to spend the night. The next morning, before getting back on the road, Houston had a snowball fight with the Martin children.

Nine years later, one of those children, Eliza Martin, became Emeline’s owner. How this could have happened, since Thomas Martin had been so supportive of the free status of Rhoda and her children, is one of several mysteries in Emeline’s case. The record does show that Martin died in 1835 and didn’t leave a will, and when the chancery court listed Martin’s property three years later, Emeline, now sixteen and valued at $650, was the property of Eliza, and Rhoda and her other children were owned by Eliza’s brother William Martin. By then Caffery had died too, and Jackson had moved to New Orleans, where he was buying and selling cotton. No one was around to speak up for Rhoda, Emeline, and their family.

In 1839 Eliza married John Seip, who soon purchased a plantation in Rapides Parish, Louisiana. The couple moved there, taking Emeline. She wasn’t the only free Negro coerced into working the sugar and cotton plantations of the area; Solomon Northup, whose harrowing account of being forced into slavery would become the book 12 Years a Slave, was sold to a man in the same parish around that time. Over the next few years Emeline would bear two children of her own, James and William.

Her time in Louisiana came to an abrupt end in 1846, when the Seips sent Emeline and her sons with an overseer to Houston to sell them. The overseer transported the small family west, and a few days before Christmas, Emeline, William, and James had a new owner, a farmer named Jesse P. Bolls. But in her new home, Emeline hatched an audacious plan. She would sue for her freedom.

In an even more audacious move, Emeline got the best lawyer in town. Peter Gray was young—at 29, he was only a few years older than his client. He had come to Texas in 1838, when it was still a republic; his father, the Virginia lawyer William Fairfax Gray, was already here, having helped negotiate a loan to the government that paid for the army. The Grays settled in Houston, where Texas president Mirabeau B. Lamar made Gray the first district attorney of Harris County. Father taught son the law, and when William died, in 1841, Sam Houston appointed 22-year-old Peter to take his place as DA. Peter was also elected to the first Legislature, in 1846, where he wrote the Practice Act, the state’s first rules of civil procedure.

On May 4, 1847, Gray filed suit on Emeline’s behalf, claiming that Bolls “with force and arms assaulted” her and “took, imprisoned, and restrained her and her children of their liberty.” Emeline asked for $500. She signed the pleading with an X. Six weeks later Gray, the expert on the new state’s civil procedure, filed an injunction to prevent Bolls from taking Emeline outside the county and selling her into slavery again. The petition noted that Emeline’s sister Lucy Thompson, who had earned her freedom and was living in New Orleans, had come to Houston and was helping her by consulting with the lawyers. Judge C. W. Buckley granted the injunction.

Both sides built their cases, sending out interrogatories. Gray sent them to witnesses in Tennessee and Louisiana who had known Emeline when she was growing up on the Martin plantation, including Washington Jackson in New Orleans and Jackson’s sister in Philadelphia. Several supported Emeline’s claims. Jackson swore that both Caffery and Martin understood that Rhoda and her children were to stay free while they worked for him. “The service of Rhoda was to be a free and sufficient compensation for her and the children’s support, until the latter should be of ages proper to be put at to learn trades,” he testified, adding, “I am confident that [Caffery] could not in any way . . . have been induced to sell Rhoda and her children as slaves. He was a kind, honorable, and honest man.”

Bolls’s lawyers found witnesses to support his property claims, such as Robert Chappell, of Washington County, who said he’d seen Emeline in Houston in late 1846 and “Emeline said to me that she was willing to be sold . . . she induced me to believe that Beckham [the overseer] had come honestly by her.” Eliza’s sister Susan Flint said Rhoda “was held by my father as a slave” and that Emeline “belonged to my father, and my sister received her as part of her share of my father’s estate.”

The case finally went to trial on November 25, 1848. There is no transcript of the proceedings, but Gray did ask the court for a jury charge: that if its members believed Rhoda was sent to Philadelphia to be free, that she was free, and that if they believed Emeline was Rhoda’s daughter, then she too should be considered free. The jury, it seems, followed this logic, coming back the same day with a verdict. “We, the jury, find for the plaintiff Emeline that she and her children are free as claimed by her and assess her damages at one dollar.”

Davidson had never heard Emeline’s story—it hadn’t been written about in the newspapers of the day. No one knew about it at Baker Botts, the firm that Gray had founded, either. “We have two histories written about Baker Botts,” says Bill Kroger, who’s been at the firm since 1989, “and numerous lawyers have written stories about cases they’ve done. But nobody mentioned Emeline.” The firm donated $5,000 to help preserve the case file, and the project helped spur other initiatives to preserve county history.

Researchers found additional cases that were similar to Emeline’s, including that of Nelly Norris—a woman with two children who had been enslaved in Tennessee and later freed but then enslaved again—who went to court for her freedom in Harris County in 1838 and won. One of her lawyers was William Fairfax Gray, Peter’s father. That same year in Houston, Sally Vince sued her owner, Allen Vince, and won when the judge ruled that her previous owner had set her free. In Moore v. Minerva, from 1856, a slave freed in Ohio had come with her former owner to Texas. After he died, she was forced back into slavery by the administrator of his estate, who said that Texas’s law prohibiting free Negroes from immigrating meant she remained a slave. The state Supreme Court ruled in her favor, declaring that she was still free. In the 1850 case of Gess v. Lubbock, a female slave had had a child with her owner, who later signed a document emancipating her. After he died, his nephew claimed her as his slave through inheritance. She lost, but on appeal before the state Supreme Court, she was awarded a new trial—and won.

“The courts of pre–Civil War Texas, especially the Supreme Court, were extremely favorable to people of color,” says Davidson. That view is echoed by other historians and political scientists, such as A. E. Keir Nash, who wrote in 1971 of the court’s “remarkable antebellum tradition of fair treatment of blacks.” But Gonzaga law professor Jason Gillmer, who is working on a book about Texas courts and slavery, cautions about seeing too much honor in these court decisions. “A lot of these cases came about because of a will,” he says. “This is about property rights, whether a person can free someone who is his property. If a man can’t do with his property what he sees fit, that would be government tyranny at its worst. These cases are a complicated mix of property rights, white supremacy, and individual exceptions, where juries came to a decision that reflected local circumstances. Maybe members of the community got to know the slave and saw her as an individual.”

In 2004 the Houston Chronicle published a series of stories on Davidson, the preservation project, and Emeline; Davidson’s own story was published the next year in the Houston Lawyer. Emeline’s tale eventually reached Andrea White, the wife of former mayor Bill White. She relayed it to her friend Sandra Bernhard, who founded the Houston Grand Opera’s community outreach program, which turns Houston stories into operas and performs them at various places in the community. Bernhard was interested in telling Emeline’s story and asked White to write it. White, who had written children’s books, volunteered to do a version of Emeline’s story. She went to Davidson, who gave her a copy of the court file; she also read other stories on Emeline, including Davidson’s.

One thing he had focused on was the mystery of Emeline’s jury. For every case before and after hers, the jury had been drawn from a pool of 36 men. However, the 12 members of her jury, Davidson wrote, had been seemingly handpicked and included important local figures like Andrew Briscoe, a former judge, and Joseph Harris, whose uncle was the namesake of the county. Davidson says that in all his research he’s never seen a special jury seated like that. Gray was a powerful, well-known man, the former DA and the representative to the Texas Legislature from the county. “The only two people who could have appointed this special jury were the judge and the district clerk,” says Davidson. “Would they have done it for Peter Gray? They would have probably done a lot of things for Peter Gray.” White was also fascinated by Emeline’s jury. “The only thing I could figure out is the judge and Gray worked together to do that,” she says.

When White finished her book, in 2014, she gave it to Bernhard, and the HGO reached out to Richard Husseini, a tax partner at Baker Botts and an opera lover, about underwriting an opera. The firm agreed. Meanwhile, Kroger had been doing further research on his own at Baker Botts, helping to solve another puzzle: why Emeline and her children had been sent to Texas in the first place. Kroger found a 1943 article by Andrew Muir titled “The Free Negro in Harris County,” in which he wrote about Emeline’s case—but also, in a surprising footnote, her mother’s. It turned out that in April 1844 Rhoda had sued the Martin family in Davidson County, Tennessee, on behalf of her and her children, claiming that, since she had been a free woman of color back in 1816 in Philadelphia, she and her children should be free then. The trial was held in 1846, and on September 21, Rhoda and her children won, with the court declaring, “The plaintiffs are free persons of colour and not slaves of the defendant.” That, Kroger concluded, was why the Seips unloaded Emeline and her kids in Texas: they were afraid they would lose them if they stayed in Louisiana.

Emeline’s story was so much grander now—the timeless fight for freedom heightened by a mother’s influence on a daughter and a father’s on a son. Everyone who heard it was transfixed, and it was as if the city of Houston was coming together—lawyers, historians, journalists, the wife of a former mayor, the local opera company—to tell it.

What would an opera about a Texas slave suing for her freedom sound like? Banjo and violin? Gospel choir? Hip-hop string quartet? What Wings They Were: The Case of Emeline is not a period piece or a hybrid. It’s an actual opera, with contemporary melodies and dramatic voices, the kind you’d see onstage in Paris or Rome. Emeline is a chamber opera, a small-scale production. In fact, the only instrument is a piano. The music was written by John Cornelius II, an associate professor at Prairie View A&M University. He is a large man who looks like he’d sing baritone; he has written opera and chamber music before as well as song cycles—both music and words. His writing partner was Janine Joseph, a young poet and professor who got her Ph.D. in literature and creative writing from the University of Houston.

Like everyone else trying to tell Emeline’s story, the two didn’t have a lot of source material, so they began with her mark. “What struck me was her X,” says Joseph. “That’s where I started.” She wrote the prologue and the first two sections of the opera and sent the words to Cornelius:

I sign my name not Emeline

but with an X

because I am now not free.

The music of Emeline is emotional and dramatic, over the top, flitting up and down over jarring piano chords and melodies while the characters sing with all the Sturm und Drang we expect from opera singers. “The challenge with doing a historical piece,” says Cornelius, “is you have to do research and know the subject, but research can be boring. What’s it about? What do they care about? What are their motivations? What do they want, what do they need?” Gwendolyn Alfred plays Emeline, and her voice is warm and high, sweet but full of sadness. Sometimes she sounds like a bird trying to break free, her powerful notes descending and then taking off again. Christopher Besch plays Gray, and his beard resembles the DA’s. Besch’s voice is impossibly deep, quavering with angst and booming with lawyerly outrage:

Gentlemen of the jury

who here dares call

this free woman of color

anything but free?

Brian Yeakley plays a composite of Bolls, Seip, and a shadowy presence called the Figure, who represents society and the “peculiar institution” of slavery.

The opera will debut April 30 at the Ensemble Theater. On May 3 and 4 it will be performed at a Harris County courthouse, near the spot where Emeline sat to be judged in 1848, and later at various middle schools and high schools. Emeline is a stirring form of community outreach, a way to get Houstonians to engage with their history in a creative way, to reach back into the past and witness a story that needs to be told.

But it won’t solve the two biggest mysteries of Emeline’s story. First, what happened to her after she won her freedom? She almost certainly left town. Free blacks were forbidden to live in Harris County unless they had permission from the Legislature. And even though most local constables ignored the law and a handful of free blacks were known to live quietly in Houston, it’s safe to assume that after Emeline’s experience in Texas, she wanted to get out. Maybe she went to New Orleans, where Lucy lived, or back to Tennessee. Unfortunately, she didn’t have a given last name, and “Emeline” was popular for both black and white girls, so it’s almost impossible to track her down.

The other riddle we’ll probably never answer is how such a powerless woman got such a powerful man to be her lawyer. Kroger thinks Washington Jackson may have played a role. Jackson saw himself as a champion of both mother and daughter, having taken Rhoda and her children to Philadelphia and testifying in Emeline’s case. Jackson knew all of Emeline’s witnesses and would have known how to guide Gray in finding them; indeed, it seems he was active in putting her case together. In one of Bolls’s interrogatories, his lawyer asks James Kirkman, Jackson’s nephew, “Did not Washington Jackson . . . say to you that he wished you to give testimony?” Kroger speculates further that Jackson, who was a well-connected businessman living in New Orleans, would have known Gray or known that he was one of the best lawyers in Houston—and that he may have accompanied Lucy to Houston.

Or maybe, Davidson suggests, it was Sam Houston who got Gray the gig. Houston certainly knew the former DA and also knew the trial judge, C. W. Buckley, who had been Houston’s attorney in his 1839 suit against Mirabeau Lamar for destroying furniture Houston had left behind at the president’s mansion. Houston probably knew all the prominent residents in the city that bore his name, which at the time had only 4,500 people and no more than twenty lawyers. And of course he had known Thomas Martin and maybe even come across Emeline or Rhoda that day in 1829 at Locust Grove.

It’s hard to say exactly what was the motivation for Gray, who was certainly no abolitionist. “I think Peter was trying to live up to his father’s reputation,” says Kroger, “and do the right thing. Also, he was trying to establish a state where the rule of law governed.”

There are no such puzzles when we look at Emeline, whose reasons couldn’t be more obvious and whose courage is, to this day, electrifying. “It’s hard to imagine that kind of struggle in 2016,” says the opera’s director, Eileen Morris. “Emeline was willing to sacrifice everything for her freedom.”

- More About:

- Texas History

- Music

- Longreads

- Houston