Q: My thirteen-year-old daughter recently spent a weekend at a friend’s parents’ ranch in North Texas. While she was there, she called to ask if she could go horseback riding. I said yes, of course. But she told me that permission had to be granted in the form of a waiver that her friend’s parents would email to me and that I had to sign and fax it back before she could go out. I did all of that, but I’ve never heard of such a thing. Have you? Is this yet another product of our overly protective, overly litigious society?

Name Withheld

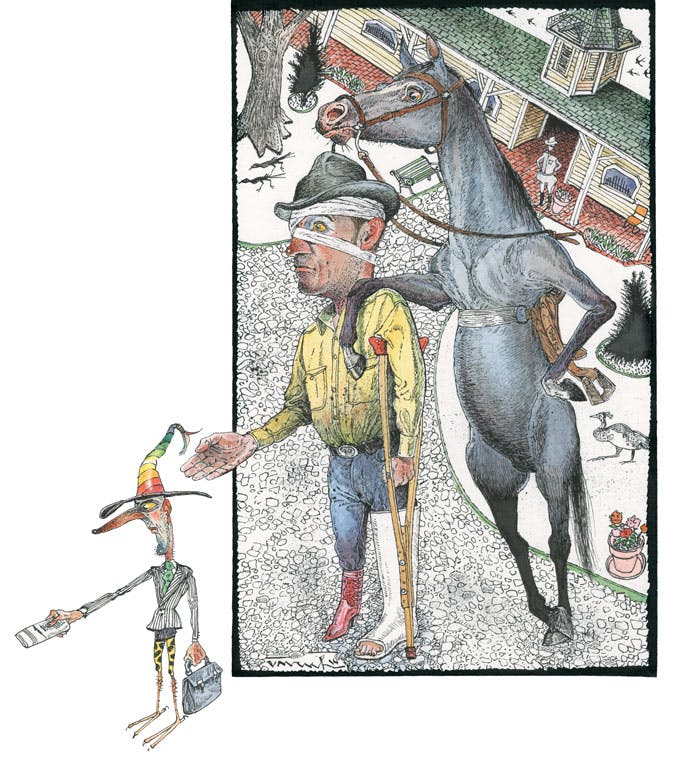

A: The Texanist does his best not to sign anything except the backs of checks, autographs, and the occasional petition in support of a statue commemorating famed San Antonio trash-barrel player George “Bongo Joe” Coleman. Thankfully, he has never been presented with a waiver like the one you describe, the basic purpose of which is to make it legally explicit that the participant in a particular leisure activity—in this case, horseback riding—is aware of the dangers associated with said activity and accepts and assumes those risks. Perhaps this is because most of the Texanist’s horse-owning friends understand that he possesses a well-calibrated sense of his own equestrian abilities. On no fewer than two occasions that he can recall, for example, he has found himself suddenly relieved of his position atop a borrowed steed. In neither case did he feel this was anyone’s fault but his own. The first was due to a simple misunderstanding between the Texanist and his mount, and the second may have resulted from one too many afternoon highballs.

Your daughter’s friend’s parents seem to be a bit less trusting than these pals of the Texanist’s, which raises a question: Just what sort of snorting, rank beast do they intend to set your daughter on top of? Sure, Hurricane may look like a docile giant, but wait until a butterfly lands on the tip of his nose and he’s gripped with a flash of panic and your daughter is thrown clear across the Red River and the only way you can think to pay for the surgeries to repair her leg is to lawyer up and sue for damages. Well, the truth is that even if they hadn’t asked you to sign a permission slip, Hurricane’s owners would likely still be protected from liability. You see, in 1995 the wise and horse-savvy folks at the Capitol saw fit to protect horse owners from such lawsuits by way of the Texas Equine Activity Limitation of Liability Act, which was amended in 2011 and is now known as the Texas Farm Animal Limitation of Liability Act. The Texanist is not a licensed ambulance chaser, but if he were one, he would avoid cases involving borrowed horses that wound or kill. The act makes it clear that because of the “inherent risk” of horseback riding and the “propensity” of a horse to “behave in ways that may result in personal injury or death to a person on or around it,” a horse owner who acts reasonably and responsibly can’t be held liable for anyone’s personal injury or death. Your daughter’s friend’s parents seem to have added a layer of protection on top of this, which is, as the owners of Hurricane, their prerogative and not, in this day and age, completely unheard of.

Q: Just how many generations can a Texan go back? If my family showed up on Ben Milam’s grant, where would that leave me?

Madeline S., Austin

A: Texas roots are a great point of pride for many of our native-born brethren and sistren, though it must be said that the actual depth measurements are sometimes exaggerated. The Texanist once shared a domino table with an enthusiastic and slightly inebriated old boy who claimed to trace his origins in the state to the Archaic period cave painters of the Lower Pecos River. “You think them good marks I used to get in art class were an accident?” he boasted. “My memaw always said it was because we was descended from the cave people in West Texas and have innate natural abilities.”

For serious genealogists, such as the ones with the Texas State Genealogical Society, a group that, among other things, doles out certificates verifying the precise profundity of one’s roots, the proof is in the family pudding. To qualify for a prized Pioneer Certificate, one must be able to show an obvious trail of pudding that goes all the way back to what they call a “qualifying person.” Each generation of forebears must be verified with references to official documents, such as vital records, probate records, and census records.

Once the various generations—for our purposes, a generation equals twenty years—are identified, the math should require no more than ten of your fingers. Let’s say you (first generation) were born in 1970, and your parents (second generation) in 1950, and your grandparents (third generation) in 1930, and your great-grandparents (fourth generation) in 1910, and your great-great-grandparents (fifth generation) in 1890, and your great-great-great-grandparents (sixth generation) in 1870, and your great-great-great-great-grandparents (seventh generation) in 1850, and your great-great-great-great-great-grandparents (eighth generation) in 1830, and your great-great-great-great-great-great-grandparents, the ones who arrived with the Milam colony, in 1810: that would make you a ninth-generation Texan, or thereabouts. Congratulations.

Q: In the sixties my husband and I were introduced to Furr’s chess pie, having never eaten anything like it before. We loved it, and since leaving Lubbock I have tried to find a similar recipe. Any suggestions?

Judi Keith, Las Cruces, New Mexico

A: The Texanist has nothing against Furr’s Fresh Buffet or its chess pie, but he must confess to you that he’s never had the pleasure of sampling the dessert you describe. Honestly, he isn’t sure that he’s ever set foot in a Furr’s. You see, the Texanist has always been a Luby’s man, his cafeteria preferences having been learned from his parents, whose post-church dining option of choice was the Town and Country mall Luby’s. The Texanist was especially keen on Luby’s famous chocolate ice box pie, though after his dad would explain that the tall, fluffy whipped-cream topping was made out of “calf slobber,” he would become decidedly less keen on it and often surrender the slice half-eaten. The Texanist’s father was a good man but not above tricking his own children out of their desserts.

The Texanist has digressed and is sorry. Despite his own personal cafeteria loyalties, he knows of no reason not to pass along some pie intel that he obtained by telephoning Furr’s HQ, in Plano. The woman he reached declined to release the actual recipe for Furr’s butter chess pie (despite his many attempts to persuade her with sweet talk), but she did offer the following recipe, from Food.com, a recipe she described as being “similar.”

Ingredients:

1 cup butter

1 cup sugar

3 egg yolks

1 egg white

3 tablespoons water

1 teaspoon vanilla

0 cups calf slobber

Directions:

1. Cream butter and sugar as if for cake batter.

2. Add egg yolks and egg white and beat until foamy; add water and vanilla, again beating until well mixed.

3. Pour the mixture into a 9-inch unbaked pie shell and bake at 350°F for anywhere from 35 minutes to 1 hour. Test with a knife. When it comes out clean, the pie is done.

If this doesn’t pass custard muster, there are always either of the two Furr’s locations in Albuquerque, just 225 miles to your north.

The Texanist’s Little-Known Fact of the Month: A 1,000-pound beef cow, after it has been slaughtered, bled, and relieved of its head, hide, hooves, heart, lungs, and other internal organs and viscera, will be converted into about 430 pounds of brisket, steak, roast, ribs, hamburger, stew meat, and other retail cuts.