Q: I know that in the rodeo sport of team roping, one of the team members is known as a header and the other is a heeler, and while those positions are pretty self-explanatory, I’m wondering what qualities might make a cowboy better suited for one over the other. Is one a better roper than the other? How do they decide who will rope which end?

Shirley Hart, New Haven, Connecticut

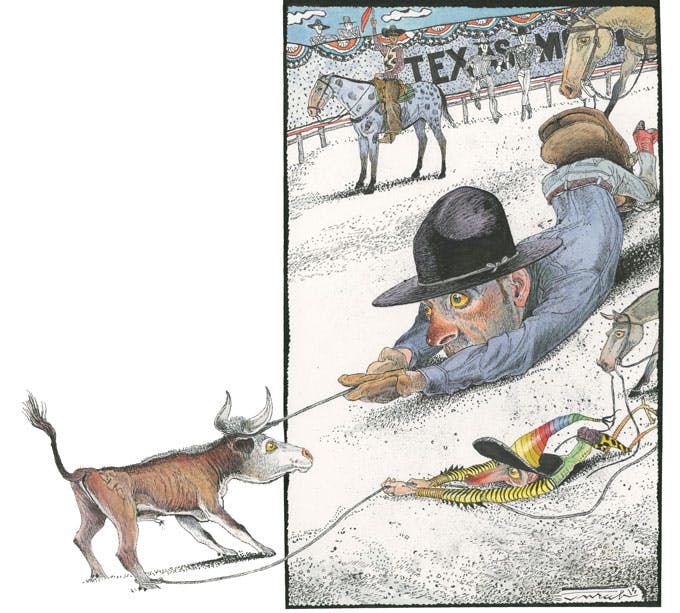

A: The Texanist is duly impressed. It is not every day that he receives a missive from up north in which the correspondent displays such familiarity with the particulars of our official state sport. He suspects that you are a displaced Texan. Unfortunately, the sad fact is, as such, you are likely to possess more knowledge of the ins and outs of a rodeo’s roping events than many folks who actually reside here, since more and more of them are displaced Connecticuters or Californians or natives of some other bland and citified place where the cowboy is an exotic and unknown creature. So let’s start with a little down-and-dirty primer. To begin with, team roping is the only real team event in rodeo. It goes like this: A steer is released into the arena, and two cowboys (cowgirls can also participate), starting out on either side of the chute from which the wily critter has been launched, give frantic chase. The header moves out first, from the steer’s rear left side, and attempts to rope the speeding animal about the horns or head. When the header’s lasso meets its intended target successfully, the rope is dallied (wrapped around the saddle horn), and he and his horse then give the steer’s front end a tug to the left, which, ideally, turns the alarmed beast enough that the heeler, who has been following along closely, can toss his lasso, with the intention of catching both hind legs and then dallying his rope. After both ropers are successful, they face the steer and put their horses in reverse, pulling the ropes taught. When the ropes are free of slack, the clock stops. Done right, all this exciting rodeo action goes down in a fraction of the time it took you to read this long-winded description. As far as unique physical or mental qualities that distinguish the header from the heeler, the Texanist does not believe there are any. However, Kirk Bray, president of the U.S. Team Roping Championships, out of Stephenville, suggests that the relationship between the two positions is akin to that of a quarterback and his wide receiver, with the header being the one who sets up and initiates the play and the heeler the one who runs across the goal line and spikes the steer in a victory dance. Okay, fine, so the heeler might be a little flashier, but the point is that neither one is a golfer. You follow? They both have to be good rope handlers and good horsemen, with exceptional hand-eye coordination and a fair amount of intestinal fortitude.

Q: My wife and I have recently started to go camping with some fellow Texans. We always end up in Oklahoma state parks, because alcohol isn’t allowed in any of the Texas state parks that we have been to. We would rather not leave the state of Texas. So are there any state parks here that would allow us to have a couple of beers by the campfire?

Name Withheld, Fort Worth

A: The closest the Texanist has ever come to making camp in Oklahoma was in the late eighties, when he accompanied some college buddies to Eisenhower State Park, on the Texas side of Lake Texoma, the aptly named Red River reservoir that we share with our neighbors to the north. This was a long time ago, but he seems to recall knocking back a few cold ones before dozing off for the night—which is to say, the Texanist may have, in his wild youth, violated the rules. Visiting our beautiful state parks makes for a fun getaway, but such adventures usually entail a host of sometimes fun-dampening regulations, such as the prohibitions against fireworks, metal detectors, and skinny-dipping. That trifecta right there cancels out one of the Texanist’s favorite activities (which he will leave to your imagination). However, as with most laws, it all comes down to interpretation. The ordinance pertaining to the consumption of alcohol is classified under “Rules of Conduct: Alcoholic Beverages” in the State Park Operational Rules. It declares that it is an offense for any person to “consume or display an alcoholic beverage in a public place.” But go to the section of the rule book known as “Definitions,” and you’ll find that a “public place” is characterized as “any place to which the public or a substantial group of the public has access.” The Texanist is not a lawyer, of course, but it is his professional opinion that there is enough leeway in that definition (you do have a tent, don’t you?) to render it wholly unnecessary for you and your friends to continue your laborious forays into the semi-wilds of the Sooner State. In fact, it turns out that you have likely misinterpreted the park rules in both states. According to Oklahoma state park bylaws, alcohol consumption is allowed only if the alcohol content of the beverage does not surpass 3.2 percent. Even your bootlegged Lone Star exceeds that.

Q: I am not a native Texan, but I did reside in the great Lone Star State for ten years when I was younger. I’m also married to a Texan. My question is, When, if ever, is it appropriate for outsiders to use the term “redneck”? I believe that the word is celebrated in Ray Wylie Hubbard’s revered song from the seventies, but my question remains: Is it usable by an outsider? Also, do you have any information about the origins and history of the term?

Christie Dufault, San Francisco, California

A: The dictionary tells us that “redneck” can signify either “a white member of the Southern rural laboring class” or “a person whose behavior and opinions are similar to those attributed to rednecks” and further informs us that both usages are “disparaging.” Sounds to the Texanist like the dictionary was written by a couple of tight-asses who need to spend more time away from their cubicles. It’s true that the word, which originated in the 1830’s to refer to the poor whites who worked the fields in the days before sunscreen, once carried a strong whiff of denigration (and perhaps moonshine). Nowadays, however, it is often employed as a term of endearment, or even a marketing strategy (how else to explain the existence of Duck Dynasty?). Like many other initially offensive terms, it has been partially reclaimed, an occurrence that this magazine noted in an August 1974 cover story about rednecks by the late, great Larry L. King, which contained the following observation: “One born a ’Neck of the true plastic-Jesus and pink-rubber-haircurlers-in-the-supermarket variety can no more shuck his key condition than may the Baptist who, once saved, becomes doctrinarily incapable of talking his way into Hell.” Mr. King, it must be said, was a bit of a redneck himself, and since many rednecks don’t like to be reminded of the intractability of their own condition by those with more attractive conditions, the Texanist would discourage you from using the word publicly. Unless you are, as seems unlikely, a redneck.

The Texanist’s Little-Known Fact of the Month: Dead Man’s Hole—a spooky, 150-foot-deep naturally formed hole in the Hill Country limestone, which you get to by heading east on FM 2147 from U.S. 281 and then south on County Road 401 (past that lonely old windmill), then turning left onto a creepy dead-end gravel road—is named for the seventeen or so Civil War–era Union sympathizers (and at least one foe of some area freedmen) said to have been deposited there.