Q: Where are you from?

A: The Texanist hails from Temple, as most readers of this column are already aware, so fond is he of colorful references to his birth and breeding. Yet such nuggets (cotton-eyed Joe lessons at Bonham Middle School, junior cotillion at the Knights of Columbus hall, homecoming mums at dear ol’ THS, and so forth) have, until now, offered but tiny glimpses of the place and times that made the Texanist who he is today. Individually they are like little lengths of funny Central Texas thread; woven together in their multitude, they form the very cloth from which the man himself was cut, the backdrop from which he was unfurled.

So let this spot now get its due. Having come about as a railroad town full of weary train travelers and wild ruffians, Temple was known in earlier times by such unvarnished monikers as Mudville, Ratsville, and Tanglefoot, the former place-names attributable to an abundance of mud and vermin, the latter to the fact that, as a historical marker in the center of town explains, “the combination of muddy streets and liquor made walking rather difficult at times.” As true today as it was back then. It has been the Texanist’s experience that, in addition to mud, there are substances that, when combined with liquor, will make walking, or even standing upright, quite impossible. Eventually, the town fathers tried the more attractive-sounding Prairie Queen, which must not have gone over very well from the get-go: “My fellow Prairie Queens . . .” The Texanist has at times wondered how the Fightin’ Highnesses of Prairie Queen High would have fared out on the gridiron. Ultimately, in honor of Bernard Moore Temple, the chief engineer of Gulf, Colorado, and Santa Fe Railway, the town was officially dubbed Temple in 1881.

And so it was from these illustrious beginnings that Temple began to take the shape that would someday shape the Texanist. His grandparents put down stakes and in 1923 brought forth his dad, a famous son (making the Texanist, in his mind at least, a famous grandson) who would go to college in Austin; fight Nazis in Italy; get a law degree from UT on the GI Bill; marry a “sweet-smellin’ West Texas gal,” as he would refer to the Texanist’s archangelic Abilene-born mother; and move home to become a respected lawyer before being elected mayor in 1976. The Texanist holds no hope of ever coming across a man so upright and at the same time so seldom uptight. Once, in a speech dedicating the Railroad and Heritage Museum, which is housed in the beautiful old Santa Fe Depot, he told a story about returning from the war. As the troop train approached Temple, he made his way up to the engine and was curtly informed that he didn’t belong there. Insistent, he explained to the engineer from where and just how truly far away he had come and that it was his intention to be the one blowing the train’s whistle when they entered town. The engineer acquiesced and the whistle blew, letting the folks that day know that Bill Courtney had made it home. After his death, in 1998, it was decided that a new Texas State Veterans Home would be built in Temple and named in his honor. He would be 87 this month.

The Texanist has digressed, but he always liked this story.

Las Cruces, the street on which he grew up, T-boned into Midway Drive, which at one time served as the edge of town. Beyond Midway there was a little shack of a firecracker stand that hummed with the talk of boys and the sorties of dratted yellow jackets. Beyond that was old man Wendland’s wooded property, where via innocent trespass one found fishing, frog gigging, and varmint trapping. Even with the danger of the oft-rumored “assful of rock salt” delivered compliments of a crazed, double-barrel-toting landowner, it was a veritable boyhood Shangri-la. And there was Bird Creek too, named for Texas Ranger captain John Bird, who lost his life in an obscure 1839 Indian battle on the stream, summarized preposterously in a local historical marker the Texanist well recalls: “With only 34 Texas Rangers he met 240 Indians at this point and routed them.”

The Texanist has digressed yet again, but he likes bits of local mythology like this. They provide the grist that is milled in the imaginations of young Texas boys.

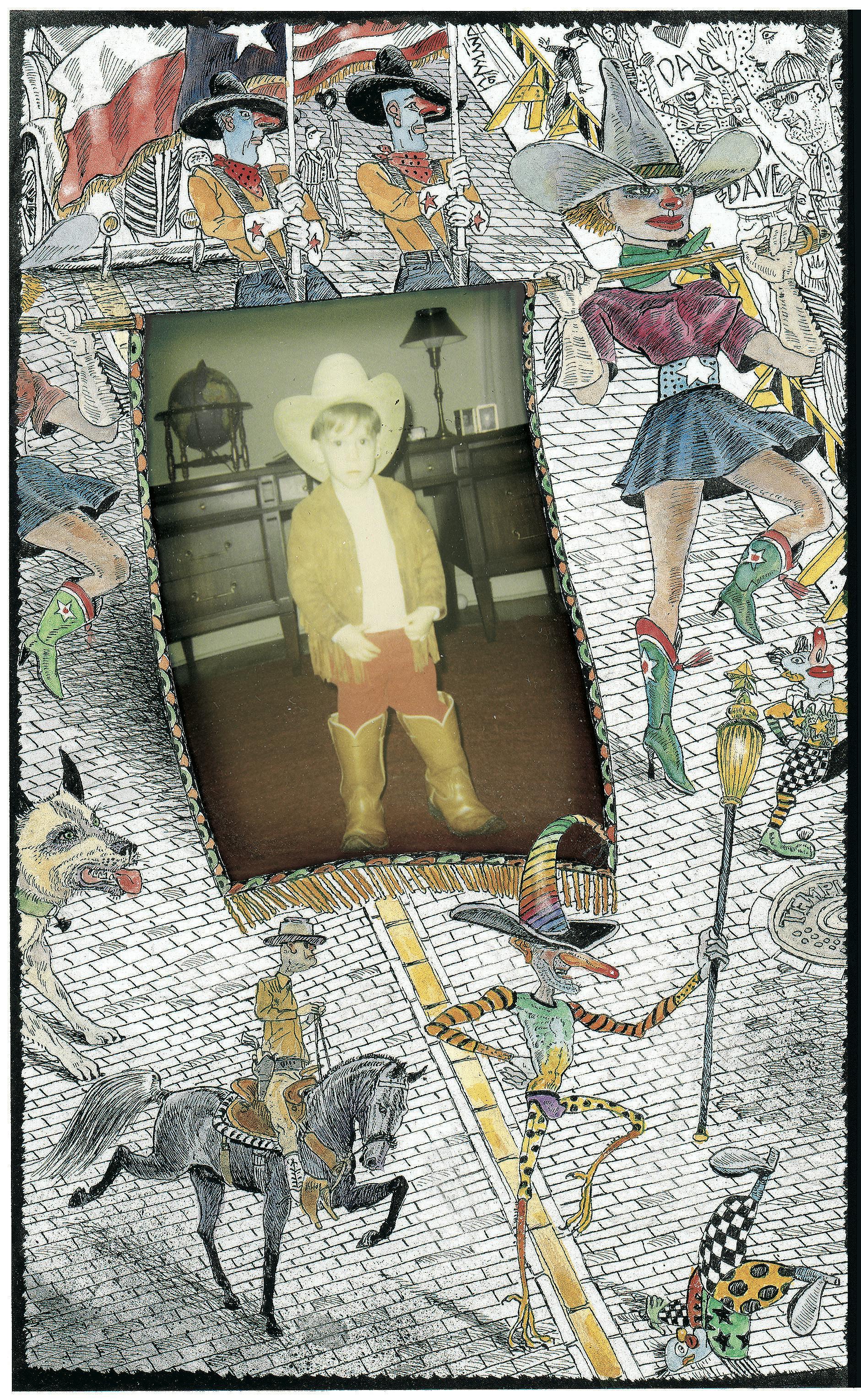

What the Texanist feels sure of is that Temple is the source of whatever authority he now claims as a purveyor of fine advice. It was where he acquired the great storehouse of info regarding Texan endeavors and ethical practices from which he draws for these monthly pages; where he was taught to dance, spit, win, lose, drive a truck, ride a horse, throw spear grass, clear mesquite, relieve a raccoon of his pelt, and keep one eye peeled for drunk boys from Rogers; where, through trial and error, he was familiarized with the ins and outs of pitching woo; where, under the good guidance of his parents, he undertook to memorize the precise location of the thin and at times invisible line separating good behavior from bad; where he learned to sit up straight, say “yes, sir” and “no, ma’am,” look a person in the eye, and never, under any circumstance, moon a city-league basketball referee. In short, Temple is not only where the Texanist is from, it is the raw material from which he was made. Even now, 26 years removed, when he peers down to find that his feet have once again become entangled in a shin-deep hole of thick black mud (real or metaphoric), rather than unleashing a cannonade of profanities, he just grins and thinks happily to himself, “Home again, home again, jiggety-jog.”