Q: My youngest boy won’t eat meat. He claims that he’s “allergic.” Is there a fix for this that will work fast enough to get him over it before the neighbors find out?

Vivian Black, Amarillo

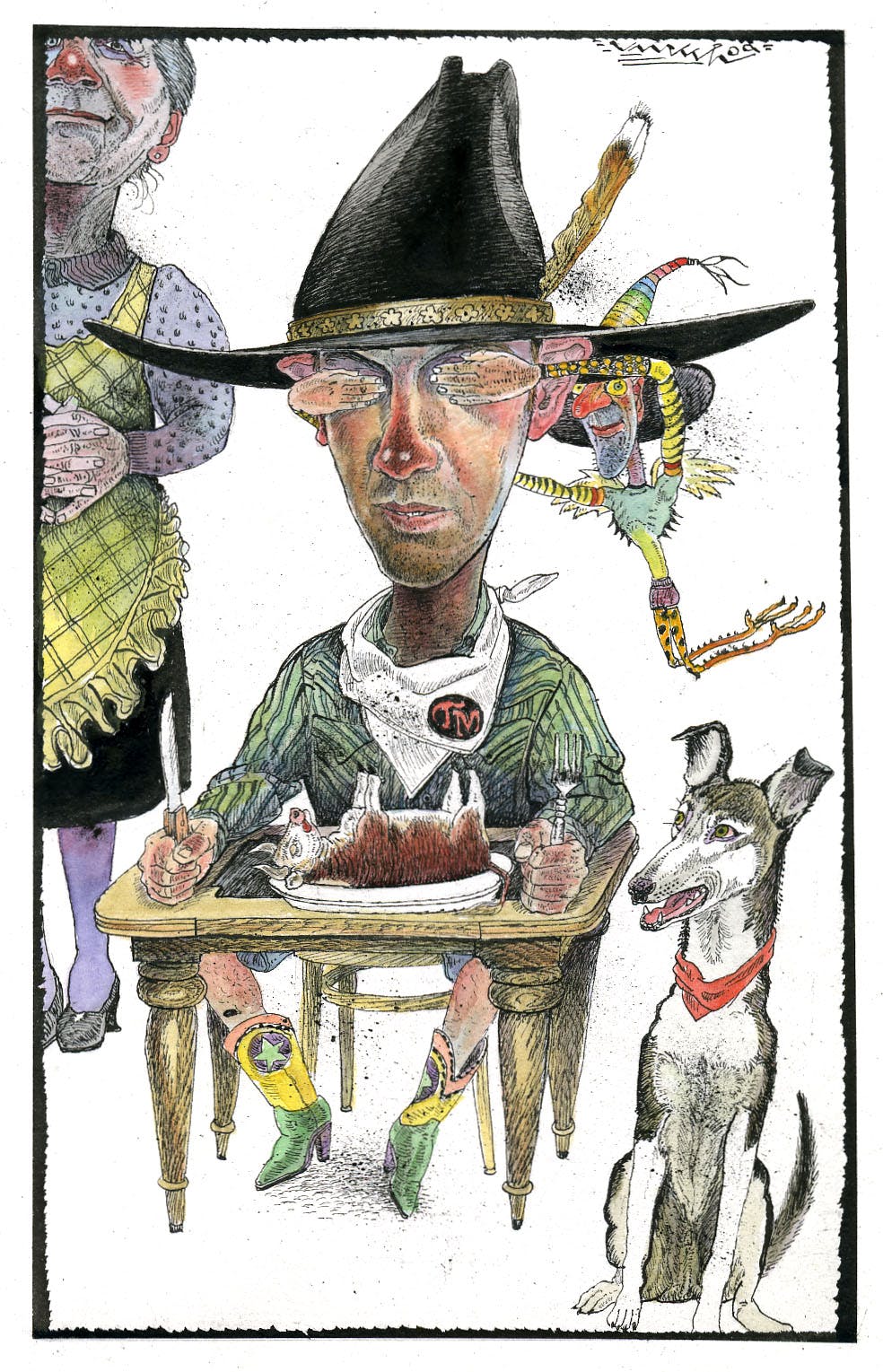

A: Appetites seem to have undergone a dramatic shift since the times when a young Texanist could be found free-ranging the streets of Temple like a hungry hound, sniffing out backyard cookouts in search of char-grilled delectables. It was common back then for a boy’s diet to consist almost entirely of meat and meat products: steaks, ribs, hams, roasts, beef patties, pork chops, sausage links, bacon, bologna, jerky, and headcheese. And Slim Jims. During this golden age of protein intake, the Texanist’s main allergies were primarily to disgusting green vegetables. Over time he became more adventurous, and his palate began to admit all manner of interesting edibles, plant matter included. Today, there are few things he will not put in his mouth: He stands before you a voracious omnivore who lives mostly free of the allergic reactions that once haunted his own mother at mealtime. Detestable brussels sprouts are the only real exception. The Texanist and brussels sprouts do not now, nor will they ever, mix. In addition to causing him great displeasure and a severely contorted face, he is certain they will also bring about a swollen tongue, a body-wide rash, a very bad case of the vapors, and, ultimately, his certain demise. As for your vexatious little vegetarian’s taking on more-carnivorous ways overnight, even if there existed a magic pill, which there does not (the Texanist looked), you probably couldn’t get him to swallow it either. Fortunately these things tend to work themselves out over time. If you must hurry things along, remind him ad nauseam that the surest route to growing up as big and strong and mildly hypertensive as the Texanist is to eat meat. Quite a bit of it.

Q: I was just in a famous hotel bar in the city that claims to be the oldest in Texas. Great watering hole, if I could just get over one thing: When asking the bartender for the nightly happy hour special, he responded that they had $2 domestics. I thought this was great news when I noticed a variety of Shiners sitting there waiting for me. I ordered an icy-cold one, but then was told that Shiner is not a domestic. When did Shiner move out of the great state of Texas? Shouldn’t the bars around the state know that it’s a beer from home and, therefore, a domestic? Am I wrong in believing that Shiner, and any other beer made in Texas, should be known as a domestic beer? If a place doesn’t consider a Texas beer a domestic beer, should I leave that bar?

Donnie P., Dallas

A: Many are the keen-of-mind soft-liquor aficionados who have experienced the same belly-souring reaction as you did after stumbling upon similar situations. This problem is rooted in standard but flawed industry lingo, rather than any screwed-up understanding of geographical boundaries. While it is indeed counterfactual—and pretty dang annoying—to encounter the claim that a product is imported when its very name indicates that it is produced in the state of Texas, this should not be cause for a great tizzy fit. In the Texanist’s mind, as well as his midsection, there’s fancy beer and there’s regular beer. The fancy stuff is often brewed in foreign localities and will sometimes find its way to a larger audience by way of importation, while regular brew comes from places like Milwaukee, St. Louis, and Golden, among other domestic brew towns. Shiner, as you indicate, comes from Shiner, here in Texas, and while it isn’t imported, it can be considered somewhat fancy and will often fall into that price category and therefore be listed under the menu heading “Imported.” Miscategorization? Technically. Confusing? Sort of. Cause to prematurely eject oneself from an otherwise comfy bar stool? The Texanist doesn’t think so. (Editors’ note: The Texanist’s background in the economics of the beer trade, while extensive, is at the same time as lopsided as his physique, with his experience coming more from the demand side of the bar than the supply side.)

Q: In this era of “globalization,” I am wondering how Texas and Texans can help maintain the “Texas identity.”

Mary Arnold, Austin

A: “Globalization,” in this era, the past era, or any future eras, has never scared the Texanist. And neither should you fear any dilution of the attributes that make Texas “Texas” and Texans “Texans.” As long as the citizenry of the Lone Star State continues to consume the “water,” in which there is believed to be “something,” the “Texas identity” should remain intact and safe.

Q: According to my wife, I snore. Having woke myself up a few times, I believe her. It’s gotten so bad that we don’t even sleep in the same room together most nights. For the sake of our marriage, what can I do?

Billy Shelby, Creedmoor

A: Many shingles scribbled with many billings have hung from the eaves of the Texanist’s many workplaces. Yet it is your misfortune that not a one of them ever read, “The Texanist: World-Famous Practitioner of the Healing Arts, Specializing in Maladies of the Ear, Nose, Throat, and Marriage.” And in truth, this is no medical matter. You, sir, are in the market for a miracle worker, and sadly these do not exist. As a young and still-impressionable man, the Texanist learned this the hard way, when certain promises relating to the improvement of his golf swing were made by a “miracle worker” in a now-defunct sports medicine institute in Nuevo Laredo. Twelve excruciating hours and one stomach-pumping later, he concluded that (a) miracles do not exist, (b) liquified donkey hoof should not be ingested, and (c) there is no shame in being a duffer. In lieu of a miracle, Billy Shelby of Creedmoor, let the Texanist advise you thusly: Get thee online and purchase every snake oil you can find that purports to cure log-sawing. Spare no expense! (But do not, under any circumstances, actually drink these foul potions.) Next, call thee an otolaryngologist’s office. Make multiple appointments. By appearing to attack your nocturnal boisterousness from multiple angles at once, you not only increase your chances of actually finding a remedy (which you never will in a million years) but at the same time slip into the mind of your missus the notion that you are putting forth a good effort toward solving the problem. She will appreciate your attempts and then be more inclined to withstand the nightly rafter rattling and floorboard shaking. Sweet dreams.