Q: My very close friend, who is a current Texas resident, constantly gives his home state of Tennessee credit for the “birth of Texas.” Tennessee played a part, of course, but I’d like to rightsize his claim. Sam Houston wasn’t even a native of the Volunteer State; he was Virginia-born. Our great state is the spawn of many nations (six flags), and that doesn’t even include the Native American tribes that called this land home. What is it that keeps this Tennessean bragging and carrying on?

Marty B., Austin

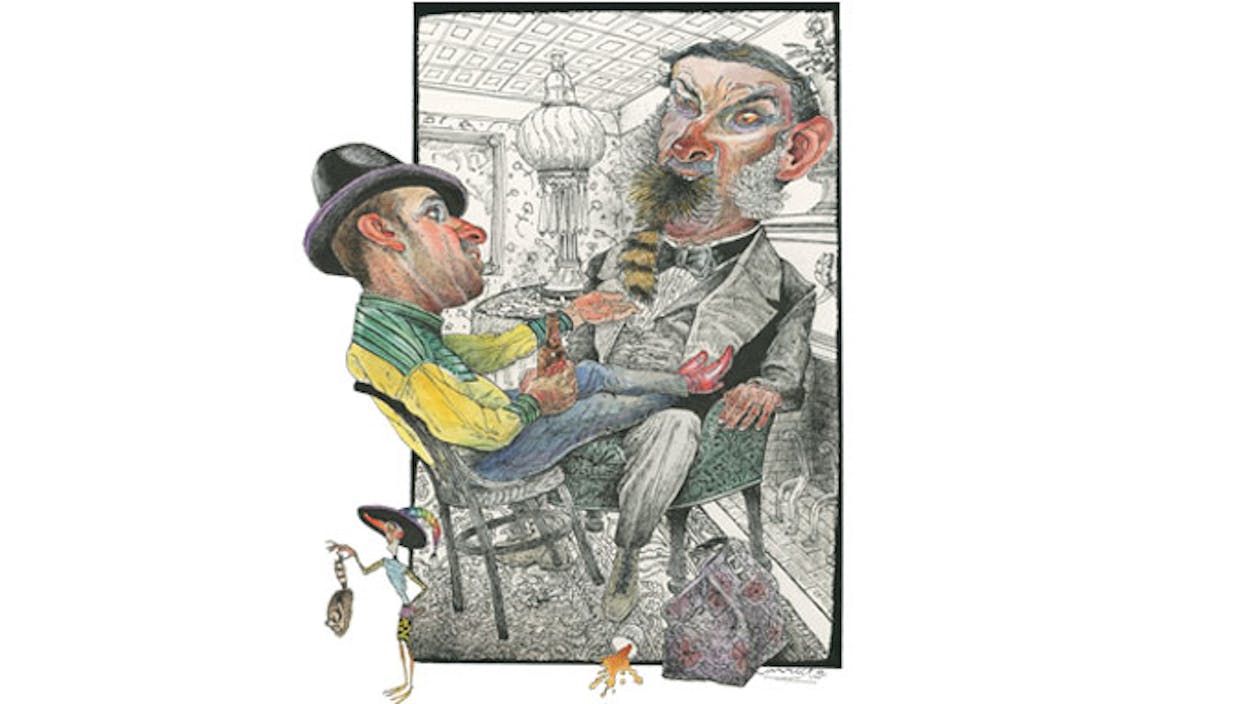

A: Your letter has reminded the Texanist of an invitation he once came across while perusing the “General Laws of the State of Texas Passed at the Regular Session of the Thirtieth Legislature, 1907.” In the spring of that year, via a joint resolution passed by its General Assembly, the State of Tennessee, in one of the largest doses of flowered-up braggadocio the Texanist has ever come across, summoned dispersed Tennesseans to Nashville for “Tennessee Home-coming Week”: “Whereas the State of Tennessee stands preeminent as the mother State of the great Southwest, having furnished the States of Texas, Arkansas, and Missouri with their ‘bone and sinew,’ [yada, yada] glorious memory of Tennessee [yada, yada] those sons and daughters who peopled their lands with Crocketts and Houstons . . .” Sheesh! The Texanist, imagining your friend spouting forth similarly from a perch on your living room coffee table after having imbibed beyond his capacity, feels your pain. Yes, Tennessee and Texas are inextricably linked. This is an indisputable fact of history with which everybody is already familiar. Why your Tennessean friend feels the need to give his home state full credit for Texas’s existence is as beyond the Texanist as it is you. Tennesseans, as we all know and as you acknowledge, played an important role. But, as you point out, so did many, many other non-Tennesseans. Your friend has gone too far. Does he also credit Tennessee for the birth of Willie Nelson because he happened to have worked in Nashville for a short period? Rather than advising you to quiet your friend with his own coonskin, the Texanist would like to invite the two of you down to the Menger Bar so that we can, preferably in the magniloquent parlance of that Tennessee homecoming invitation, hash this out further.

Q: I live in Philadelphia but was in Austin recently visiting my daughter. She lives in a tiny apartment with a girlfriend, so we went out for almost every meal. We also went out for drinks after dinner a few times. What’s the deal with Topo Chico? Is it a Texas thing? I’d never even seen it before, much less tasted it, but it seemed to be everywhere. Before my trip was over, I was craving it. Now I’m back in Pennsylvania and can’t find it.

Pauline Legg, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

A: Topo Chico, for the yet to be initiated, is a sparkling mineral water known for its exceptionally powerful effervescence. It is also thought by some to possess curative qualities, and there is even a legend that has this very elixir relieving an Aztec princess of a terrible illness. Bottled since 1895 at its source at the base of Cerro del Topo Chico, a small mountain located in the Mexican state of Nuevo León, the magical and refreshing H2O has been available in Texas since 1987. Nowadays its distribution includes most all of the United States, including Pennsylvania. The Texanist has been a Topo convert for a long time. The office fridge is always stocked with it, and he is thankful that he is allowed to enjoy it gratis, which he does throughout the day. He likes it plain, in the bottle or from a glass. With or without ice. Or, lately, in his margaritas or Mexican martinis. Or, especially, in his Chilton cocktails. Or just mixed with fresh juice. Or, like the Austin hipsters, as a side to his morning coffees. Or, on particularly rough mornings, as a splash in the face. It’s really good water.

Q: I practically grew up on Possum Kingdom Lake, going there with my parents as a child and on weekends with friends during high school and college. Now I take my own family on occasion. What a beautiful place it is. But I’ve always wondered where the lake got its weird name. Do you know?

Brian Belsen, Dallas

A: Your fondness for this peculiarly named North Texas body of water is understandable. Possum Kingdom Reservoir, a.k.a. Possum Kingdom Lake, or just PK, is a scenic beauty indeed. The Texanist has great memories of his time on Belton Lake, where he did a fair amount of adventuring during his high school days. More straightforwardly than is the case with Possum Kingdom, Belton Lake takes its name from nearby Belton. Such were the good times spent out on that reservoir that the Texanist once considered writing a memoir of the period. But he only ever got as far as a title: “Goodbye to a River of Malt Duck.” Alas, you have come in search of information about a different lake. In 1905, decades before the portion of the mighty Brazos River that runs through Palo Pinto County was impounded, in 1941, a Russian Jew named Ike Sablosky moved from Philadelphia (or maybe Indianapolis) to Mineral Wells in order to “take” the town’s famous waters, hoping to relieve a chronic stomach malady. Sablosky, who was apparently cured of his ailment in a short ten days, stuck around, eventually making a name for himself in the area’s fur trade. As the story goes, his most fruitful trappers hailed from the very valley where the river was to be dammed, and that further, Sablosky would greet these fellas each time he saw them with a hearty “Well, here come the boys from Possum Kingdom.” As strange a thing as that was to say to somebody, area folk must have liked the ring of it, because when the time came, years later, to name their new body of water, they decided on Possum Kingdom Reservoir.

Q: My husband owns a 1948 Chevrolet pickup. It is considerably rustier than when my then-future husband drove it, in the early seventies, from Brownwood to Mullin to pick me up for dates. The fact that it had no gas gauge resulted in many a night of arriving home on foot in the wee hours and being greeted by my irate father on the front porch. Since then, the truck has sat on our small farm awaiting that far-off day of restoration. My question to you is, should I make my husband get rid of the eyesore? Or should I allow him to keep his fantasy of one day driving down the road in a gleaming new old Chevy pickup truck?

Shawn Loudermilk, Early

A: Somewhere beneath the Texanist’s crusty exterior, believe it or not, lies a romantic of the old school. As such, it is very clear to him that as far as your husband is concerned, this truck is much more than the rusty, dilapidated, yellow jacket–infested heap it appears to be. For him it is emblematic of those times when a 25-mile trip out to Mullin in a two-decade-old truck with no AC and no radio to pick up his sweetheart for a little courting was no big deal. Remember, y’all would pack a blanket and head out toward your favorite spot to run out of gas. From the bed of the old Chevy y’all would stare up at a star-filled sky and dream about one day getting a place up the road in Early and settling down. Yes, those were the days. So while you may see a broken-down old truck littering your property, the Texanist is sure that your husband sees something altogether different, namely the Loudermilks’ more salady days. Therefore, the Texanist must recommend a full restoration. With a little elbow grease, the truck can be up and running (out of gas) in no time.

The Texanist’s Little-Known Fact of the Month: The memorably bombastic voice of iconic cartoon rooster Foghorn J. Leghorn was based on the speaking style of fictional senator Beauregard Claghorn, an outlandish character who appeared on the popular forties radio broadcast The Fred Allen Show and whose own voice was based on a real-life Texas rancher with whom Senator Claghorn’s creator once hitched a ride.