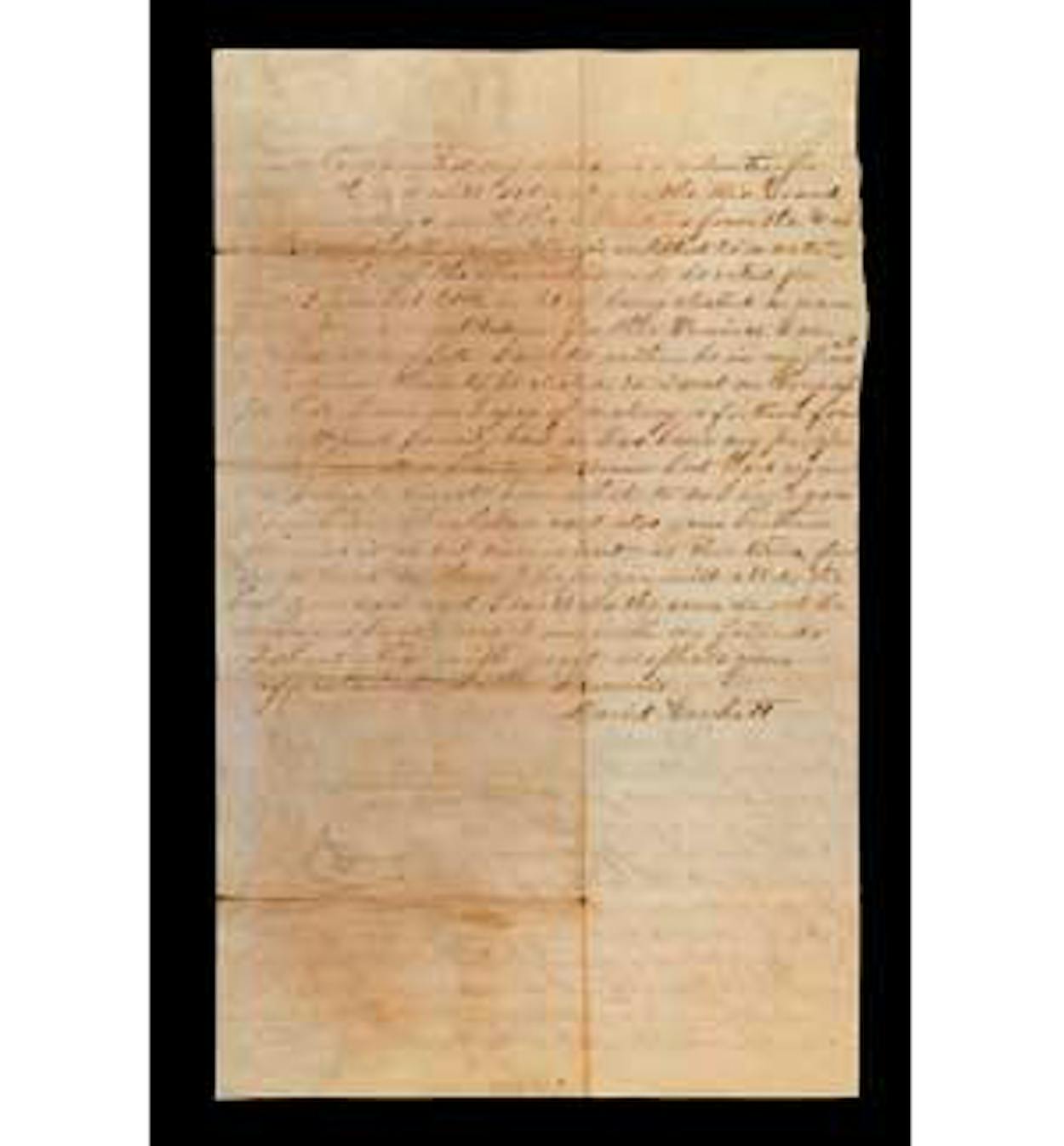

On January 9, 1836, Davy Crockett sat down to write a letter to his daughter Margaret and her husband, Wiley Flowers. During Crockett’s three terms in the United States Congress, he had written numerous letters and even published an autobiography, A Narrative of the Life of David Crockett of the State of Tennessee. But after being voted out of office in 1834, he had seldom bothered to write anything at all. Having only recently arrived in Texas, however, he was spilling over with enthusiasm for the country and for the life he thought he could have here. The extravagantly friendly reception he had received in Nacogdoches had left him almost giddy; he wrote to his daughter and son-in-law back in Tennessee because he wanted them to know that he was not just a defeated congressman with few prospects but a famous and popular personage with real opportunities in a new land: “I must say as to what I have seen of Texas it is the garden spot of the world the best land and best prospect for health I ever saw is here and I do believe it is a fortune to any man to come here.”

On January 9, 1836, Davy Crockett sat down to write a letter to his daughter Margaret and her husband, Wiley Flowers. During Crockett’s three terms in the United States Congress, he had written numerous letters and even published an autobiography, A Narrative of the Life of David Crockett of the State of Tennessee. But after being voted out of office in 1834, he had seldom bothered to write anything at all. Having only recently arrived in Texas, however, he was spilling over with enthusiasm for the country and for the life he thought he could have here. The extravagantly friendly reception he had received in Nacogdoches had left him almost giddy; he wrote to his daughter and son-in-law back in Tennessee because he wanted them to know that he was not just a defeated congressman with few prospects but a famous and popular personage with real opportunities in a new land: “I must say as to what I have seen of Texas it is the garden spot of the world the best land and best prospect for health I ever saw is here and I do believe it is a fortune to any man to come here.”

Because of that phrase describing Texas as “the garden spot of the world,” this letter, the last that Crockett ever wrote, has been quoted in nearly every history of the Texas Revolution, from scholarly tomes to grade-school textbooks; in every biography of Crockett; and in most accounts of the Battle of the Alamo, where he met his death less than two months later. But anyone who checks the notes and sources of these books discovers that the authority for this letter is simply that it has been quoted in previous books or articles. None of the historians, textbook writers, or biographers had ever seen the letter themselves. In David Crockett: The Man and the Legend, which is still the standard biography even though it was published 52 years ago, James Atkins Shackford wrote that the letter was in the hands of J. D. Pate, of Martin, Tennessee. Not only was this fact never verified, but Mr. Pate has never been found.

Assertions on such slight authority are barely more than rumors, so scholars long ago accepted that the letter had probably been destroyed somehow, another bit of history lost forever. Then, last September, in an elaborate ceremony at the Bob Bullock Texas State History Museum, in Austin, Governor Rick Perry announced that Crockett’s famous epistle had reappeared. What’s more, the Texas Historical Commission planned to purchase it, pending authentication, for $550,000.

Perry’s announcement was met with groans among the small but intense community of Texana collectors and dealers, Alamo enthusiasts, amateur and professional Texas historians, and grown men still fixated on Davy Crockett. To begin with, the letter’s seller, Ray Simpson III, was the grandson of William Ray Simpson. The elder Simpson was a cagey, slightly stuffy gentleman who in his youth had been a minor acolyte of Ezra Pound’s and who, in 1962, founded the Simpson Galleries, in Houston. His shop, then on Main Street a few blocks west of downtown, was home to a fascinating hodgepodge of antiques, fine art, silver, jewelry, books, and manuscripts. But it was also the source of some of the fraudulent documents in a seventies forgery scandal over printed matter from the era of the Texas Revolution. Simpson denied knowing that the materials he sold had been forged, but not everyone was convinced.

William’s son, Ray Simpson II, joined him in the business in the early seventies. According to Ray II, in 1986 a man claiming to be one of Crockett’s great-great-grandsons visited the galleries with a shoe box containing two letters written by his famous ancestor. Unfortunately, the Simpsons did not retain any supporting documents showing the man’s name, the exact date of the purchase, or the amount paid for the two letters. One letter was addressed to Crockett’s publisher; William sent it to be auctioned by Butterfield & Butterfield (now Bonhams and Butterfields) in California. The second was the “garden spot of the world” letter; William decided not to sell it right away. As Ray II remembers it, his father kept the famous letter in his office, even though the room was overflowing with books, letters, papers of all description, files, and bric-a-brac. William was splitting time between Houston and Florida in those days, and during one of his absences, his secretary took it upon herself to clean up his office. After that, no one could find the Crockett letter.

William died in 2001. In 2007 the gallery moved several miles west of its Main Street location. While cleaning out his father’s office, Ray II found a folder in a pile of old magazines on top of a filing cabinet. In the folder, between some plastic sheets, was the long-lost letter. That was a happy moment. Ray II turned the letter over to his son, Ray III, who now runs the gallery. Ray III immediately went into action.

Over the years, he had sold some historic Texas paintings to John Nau, an intellectually inclined Budweiser distributor from Houston who was appointed to the Texas Historical Commission in 1993, elected chair of the commission in 1995, reappointed as chair in 1999, and reappointed again in 2003. Ray III contacted Nau about the letter, and Nau decided that the commission ought to move quickly to buy it before it was offered in an open auction. With the governor’s encouragement, Nau called an emergency session of the commission’s executive committee on August 28, 2007. He told the committee that whereas bids at an open auction would begin around $250,000 and probably rise to $750,000, or even $1 million, Ray III was now offering the letter for $550,000 and was willing to give back $60,000, making the total cost to the State of Texas only $490,000. The commission happened to be sitting on $823,000, authorized by the Legislature for a special artifact fund, that needed to be spent by August 31, just three days away. Whatever money the commission failed to spend would be rescinded. After hearing Nau’s presentation, the committee voted unanimously to purchase the Crockett letter.

Anyone who knew about collecting historical documents had to be skeptical. There had been William Simpson’s unfortunate sales of forgeries in the past, and now here was this document appearing out of thin air, supposedly obtained from an unknown and untraceable seller more than twenty years ago. But when doubts began to appear in newspaper stories, Ray III was indignant. “I am very positive that this is the original Davy Crockett letter,” he told the Austin American-Statesman. The historical commission initially took a similar position. “I am 99.9 percent sure this is the real letter,” said senior communications specialist Debbi Head. Three days later, the commission retracted this statement, explaining that Head’s comments were a “misstatement.”

At the time of this writing, the commission is awaiting the results of forensic tests that will determine whether the ink and paper together could date to 1836. If these tests are positive, and I believe they will be, then the document will go to handwriting experts to determine if the hand is Crockett’s. But the commission can tell its experts to go home, since a slight bit of sleuthing can prove beyond a doubt what this letter really is. It’s neither genuine nor a forgery. It’s a copy made in the years after the original letter was written. In Crockett’s day, it was common for family documents with either real or sentimental value to be copied by hand for various family members. Crockett rarely wrote letters to any of his six children. It’s not surprising that when he finally did, copies were made.

There are probably no outright villains in the story of how the State of Texas came to believe that this reproduction was the real thing, but there certainly aren’t any heroes. It’s regrettable that Ray III didn’t conduct the proper research himself before offering the letter for sale. As a third-generation dealer, he should have known why such research was necessary. We can blame the historical commission’s lack of skepticism on the confluence of a dealer who knew how to maximize value, state officials in a hurry to be gullible, and a pile of money waiting to be spent.

The proof that this letter is a copy lies in its provenance, which can be traced conclusively to one of Crockett’s granddaughters. First, there are actually two different letters, generally similar but different nonetheless, that purport to be the one Crockett wrote on January 9, 1836. The first, which I’ll call the Texas Letter, is the one the commission is examining. The second, the Tennessee Letter, is in the special collections of the library of the University of Tennessee.

Let’s look at the Tennessee Letter first. Unfortunately, the actual document is not in the library. What the University of Tennessee has is not a manuscript at all but a photocopy that was donated to the library in the fifties or sixties by Stanley J. Folmsbee, a history professor at the school. The location of the original is unknown. This is the version of the letter quoted in Shackford’s 1956 biography of Crockett. Its wording is fairly close to the text of the Texas Letter, but the spelling is dramatically different. “Son” is spelled “sone,” and “opportunity” is spelled “opertunity,” to mention only two examples. This document is one of three things: a photocopy of the original letter, a photocopy of a copy of the original letter, or a photocopy of a forgery. I think we can exclude the last possibility. Why would anyone forge a document, never offer it for sale, and donate a photocopy to a library? If this is a photocopy of the original letter, then that only emphasizes that the Texas Letter is a copy. The Texas Letter’s copyist simply cleaned up some of the original’s spelling errors. If the Tennessee Letter is a photocopy of a copy of the original, then it doesn’t have much relevance to the Texas Letter and is of interest only to historians who might choose to ponder the significance of the slight differences in wording.

The provenance of the Texas Letter is much clearer. Crockett’s second wife, Elizabeth, along with two of her children by him, moved to Texas in 1852. They settled on land deeded to them by the state legislature near Granbury, southwest of Fort Worth. Several years after that Colonel John H. Traylor, who would later serve as a state senator and the mayor of Dallas, met Crockett’s son Robert and cultivated enough of a friendship with him and the other Crocketts in the area that the family loaned Traylor several family documents to use in writing a biography of Davy Crockett.

Traylor’s book was never published. But on June 1, 1913, as the town of Acton was preparing to unveil a statue of Elizabeth Crockett, the Dallas News published an unsigned story that quoted Crockett’s letter in full, citing Traylor’s manuscript as the source. The wording of this letter is identical to that of the letter the commission is now considering. Traylor had evidently used the letter in his biography. The article clearly states that the letter he consulted was a copy: “As an evidence that [Davy] was fairly well educated, I here insert the copy of a letter he wrote to his daughter Margaret” (emphasis mine). The paper quotes Traylor as saying that the copy was then in the possession of Crockett’s granddaughter, a Mrs. Martha M. Parks, of Granbury.

The Texas Letter was quoted in full again in “A Critical Study of the Siege of the Alamo and of the Personnel of Its Defenders,” a paper by Amelia Williams published in the Southwestern Historical Quarterly, in October 1933. Williams, however, merely quotes the letter as it appeared in the Dallas News story and repeats that it’s owned by Mrs. Parks.

Years later, a woman named Mrs. Sides bought an unopened trunk at an estate sale in Granbury. Inside she found a number of Crockett family documents, including the copy of the famous last letter. Again, the text was identical to what had appeared in the Dallas News. Sides took the letter to the Log Cabin Village, a museum in Fort Worth, where she solicited the help of a staffer named Bettie Regester, who arranged for the letter’s consignment with W.M. Morrison Books and Publishing, in Waco. The letter was sold in 1975 for $3,000.

Nothing is known about Mrs. Sides other than her last name. Regester is deceased, as is W. M. Morrison. Morrison’s daughter-in-law told me that his records from that sale have been lost, so it’s impossible to discover who bought the letter in 1975. Fortunately though, Regester kept photocopies of all the letters that Mrs. Sides brought to her.

In 1979 or 1980, a man named Darby Kurtin, whose wife, Terri, is a direct descendant of Davy Crockett’s, was doing genealogical research at the Log Cabin Village. Regester made Kurtin a copy of her copy of the Crockett letter. The text of Kurtin’s copy is identical to the text quoted in the Dallas News in 1913, and in appearance the letter is obviously the same as the one now under consideration by the historical commission.

It’s clear, then, that the document Colonel Traylor quoted in his book and described as “the copy” of the original letter was the same one that Martha Parks, of Granbury, owned; the same one that Mrs. Sides purchased at an estate sale and brought to Bettie Regester; the same one that W. M. Morrison sold on Mrs. Sides’s behalf in 1975 for $3,000; the same one that Regester copied for Darby Kurtin in 1979 or 1980; the same one that a mystery Crockett descendant brought to William Simpson in 1986; and the same one that Ray Simpson III is now offering to the State of Texas as the original letter. It’s not.

And what of the original? Anyone who owned that letter and knew what it was would have come forward after hearing that Texas was willing to pay $550,000 for it. Since no one has, the letter could be lost, pressed between the leaves of a book, or locked in some forgotten trunk in an attic. But more likely, it disappeared long ago, burned or crumpled to dust or tossed out in a pile of rubbish. Which means that the Texas Letter does have value, after all. Copy though it is, it turns out to be the best source for the text of Davy Crockett’s last letter. And Texas should buy it for, oh, maybe $10,000, perhaps $20,000, but certainly not half a million.