The kid was a full-blown sports prodigy almost from the time he could walk. He was driving golf balls at the age of two, beating adults when he was ten. In youth baseball he hit so many home runs that the league installed a twelve-foot net over the fence. He responded by clearing it, once even breaking a window in a nearby house. When he was in seventh grade, he could stand on the 50-yard line, take a crow hop, and throw a football through the goalposts. He was descended from a long line of ferocious competitors—boxers and football players and drag-boat racers and cockfighters and scratch golfers and people who hated to lose even a friendly card game with their own children. Over the generations that fierce desire to win had been distilled repeatedly, reduced to a powerful concentrate that ran in the kid’s veins like an electric current. In high school he was a two-sport athlete: a spectacular, record-setting quarterback and an All-District shortstop who hit .416. As a nineteen-year-old redshirt freshman at Texas A&M, he set the world on fire, electrifying college football fans with his speed and swagger on the way to winning the Heisman Trophy. The kid never stopped moving. If he wasn’t on the field, he was hunting and fishing in the forests and creeks of the Hill Country, where his parents lived, or the lakes and piney woods of East Texas, where his family has deep roots. And even then he hated to lose, had to catch more fish and bag more bucks than anyone. The kid was wired in every possible way to need to win, no matter the game, no matter the opponent. But on the evening of August 4, 2013, he was facing the possibility of a major, soul-crushing defeat.

It was the night before Texas A&M’s fall training camp, and several hours earlier, the news had broken that the NCAA was reportedly investigating the kid for getting paid during the off-season to sign memorabilia, a violation of the league’s amateurism rules. Instead of strolling into camp the next day as a conquering hero, he would arrive under a cloud of doubt, with questions swirling about whether he would even get to play. As he practiced that week, the storm of negative publicity just got worse, as allegations from various anonymous sources rolled through the Internet and denunciations rained down on him from all sides.

For anyone paying attention, the moment had a distinct sense of déjà vu. One year earlier, when the kid was still unknown, he had hit what had seemed at the time like his lowest point. It was the early morning of June 29, 2012, and he was sitting in a College Station jail cell, having been arrested for fighting and booked for disorderly conduct, failing to properly identify himself, and carrying phony driver’s licenses. The arresting officer’s report identified him as Johnathan Paul Manziel. Age: 19. Height: 6”1’. Weight: 195. It also noted that his breath smelled of alcohol and that “his speech was slurred when he spoke.” The mug shot showed him looking grim, glassy-eyed, shirtless, and obviously very unhappy.

For Johnny Manziel, “the incident,” as his family and coaches called the 2012 arrest, had marked the end of a long, slow slide into a dark place. It had begun when he’d been redshirted in his first year at Texas A&M, meaning he could practice with the football team but not play in games. Though redshirting is common enough, for a kid as desperate to play and win as Manziel was, it was a minor disaster. He hated riding the bench; through fall practices he felt adrift, without purpose. When his redshirt season ended and he joined the team’s official roster, in the spring of 2012, he seemed to have lost the spark that had made him so good in the first place. He played worse, in his own estimation, than he’d ever played in his life. It seemed impossible that he could land the starting quarterback job, especially after a mediocre performance in the intrasquad Maroon and White Spring Football Game. Jameill Showers, a cannon-armed sophomore from Killeen, would likely be A&M’s quarterback that fall, and Manziel would sit, miserable and aimless, all that competitive juice turning sour in his veins. As spring gave way to summer, he fell even further into a funk, fighting with his family and, as he puts it, “just being too wild of a college kid.” And then came the arrest. The week that followed was full of urgent meetings with his coaches and parents to discuss his future and news in the local press about how Manziel had blown his chance to ever be A&M’s starting quarterback. He became deeply discouraged, telling his mother that if this was what college football was all about, he wasn’t even sure he wanted to do it anymore.

But fate had other plans. Just over five months after the incident, a dapper, bright-eyed Manziel, known to the nation and to vast numbers of sports fans worldwide as Johnny Football (and to many online as the more emphatic Johnny F—ing Football, or JFF), stood on a stage at the Best Buy Theater, in New York City, and became a legend: the first college freshman in history to win the Heisman Trophy. In that time he had emerged from the obscurity of the Texas Hill Country—unheralded, unhyped, and underrated—to exhilarate the nation with a frantic, improvisational style of play that sometimes seemed as if it belonged more in a video game than on the gridiron. In the Southeastern Conference, America’s toughest football conference, he set the all-time record for total offense, breaking 2010 Heisman winner Cam Newton’s record in two fewer games. He broke the legendary Archie Manning’s 43-year-old SEC record for offense in a single game. He and his insurgent Aggies shocked the world by beating national champion Alabama. And in case there were still doubters—with Manziel, there are always doubters—a month later, at the Cotton Bowl Classic, he engineered the wholesale destruction of a very good, eleventh-ranked Oklahoma football team. His team, which many had predicted would struggle that year, finished 11-2, ranked fifth.

But Manziel did more than just send 350,000 living Aggies into paroxysms of joy with his victories on the field. His Heisman season unfolded at a time when deep currents of change were running through Aggieland itself. A number of years before his arrival at Texas A&M, the university had launched a major campaign to finally make the public understand that it was no longer the same old narrowly regional school that labored in the eternal shadow of the University of Texas but the diverse, highly ranked global research university it had quietly become. In fact, its 2011 decision to join the SEC was in large part an attempt to refashion its image as a national university. The pitch had been working: applications since 2003 had nearly doubled. Still, old feelings and stereotypes lingered.

Then along came the kid. Perhaps the most amazing thing he did last fall—and what may turn out to be his most lasting contribution to the Aggies—was to allow Texas A&M to finally emerge, as if from a chrysalis, with a fully formed new identity. It is hard to pinpoint exactly when it happened. For some it was the Alabama game. For others it was the nationally televised stomping of its former Big 12 rival and tormentor Oklahoma. But it happened. Ask any Aggie. With an enormous whoosh that you could feel in the farthest reaches of Aggieland, those old burdens were suddenly cut loose: the chip on the shoulder about UT; the Big 12 and all its baggage; the old idea that A&M would never be anything more than a dull regional school. The signs at Kyle Field saying “This is SEC Country” suddenly seemed less like parting shots at UT than beacons of a new age.

“It was amazing to experience it,” says vice chancellor of marketing and communications Steve Moore. “Everything was bigger, the ocean was wider, the sky was higher.”

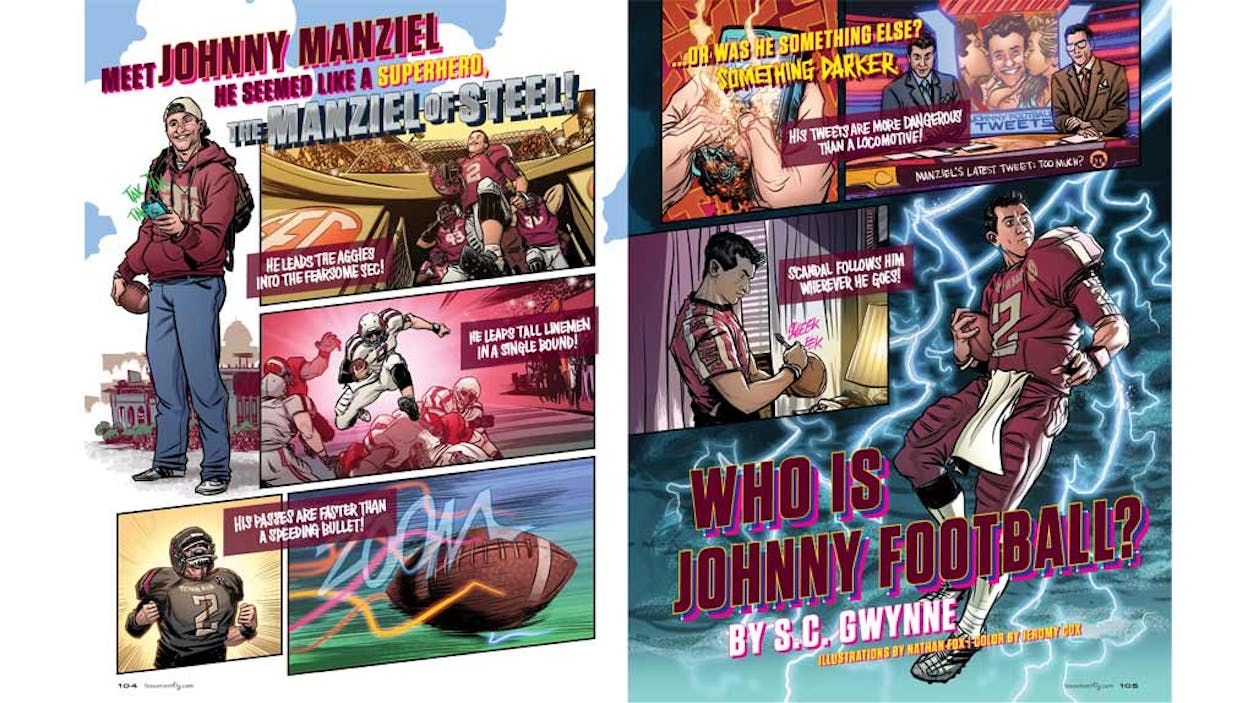

But not necessarily for Johnny Manziel. For the kid, who had become instantly famous and who was not shy about enjoying the fruits of his gigantic, Bieber-like celebrity, the sky began closing in on him as soon as he won the Heisman. In the months since then, he has lived in a world of constant controversy, much of it of his own making. No college athlete has ever achieved quite the level of fame that Manziel has, and no Heisman winner has ever lived in as relentless a media environment. Everything he does is examined and found wanting. It has appeared, at times, as if Manziel, like an immature superhero, possesses a special power he does not yet know how to use. He sends a careless Tweet and blows up his entire month. On online message boards and comment threads, vast numbers of critics—many of them fans of rival schools, it should be noted—wait eagerly for the great football star to fall dramatically to earth. And on August 4, they seemed to get what they were waiting for.

It will likely take months, if not years, to sort out the impact—to say nothing of the facts—of Manziel’s alleged actions. But this much is clear: his greatest strength is perfectly intertwined with his greatest weakness. Everything he touches, bad or good, goes uncontrollably viral. On the football field, he cannot be stopped, and off the field, the stories and pictures and rumors about him that spread throughout our hyped-up, 24/7, crazy-making news cycle cannot be stopped either. One year ago, he was unknown; today he is a kind of mythical creature. It makes you wonder, What planet did this kid come from?

Johnny’s grandfather Paul Manziel is telling me one of his favorite stories. I’m at a Manziel family dinner at the splendid lake house of Johnny’s uncle and aunt Harley and Bridgette Hooper, who own the nicest clothing store in Tyler. It’s one of five vacation homes belonging to Johnny’s relatives, all in close proximity on Lake Tyler—a sort of Manziel compound, complete with decks and docks and boats and fancy boathouses. As Paul tells it, sometime in the forties, his father, Bobby Manziel, the family patriarch, was locked in a business negotiation over oil leases with none other than Harry F. Sinclair, the founder of Sinclair Oil and one of the richest oilmen in America. Both men were tough negotiators, and neither would give in. Finally, Bobby said that he would agree to the deal only if Sinclair threw in the ring on his finger, an enormous chunk of gold inset with a gigantic diamond. Sinclair thought for a moment, then took the ring off his finger and rolled it across the table to Bobby. The deal was done. With a flourish, Big Paul—as he is called to differentiate him from Johnny’s father, Paul—takes that same ring off his finger and hands it to me. It is staggeringly large and beautiful.

It is also a perfect introduction to the extended, close-knit, Lebanese American family that constitutes the genetic and cultural origins of Johnny Football. Though Johnny gained his first fame playing football for Kerrville’s Tivy High, his roots are really in Tyler, where being a Manziel means something very special indeed. Bobby, whom he resembles, came to America from Lebanon at the age of five and rose to become one of the most successful and wealthy oilmen in East Texas. He owned banks, hotels, newspapers, and other real estate; was an accomplished pilot and skywriter; lived in a mansion with servants; and had a farm with its own runway. Known for his signature trench coat, fedora, and ever-present cigar, he was a major force in the oil business. His discoveries include the Hawkins Field, at one time the second-largest producer in the United States. His wells eventually produced more than a billion barrels of oil. His children, including Johnny’s grandfather Big Paul, were driven to school by chauffeured limousine. The Manziels entertained celebrities, from Senator Lyndon B. Johnson and Congressman John F. Kennedy to Governor Allan Shivers and comedian and fellow Lebanese American Danny Thomas.

Bobby had been a dazzling athlete too, a small, wiry, blazingly fast kid who played quarterback in high school in Fort Smith, Arkansas. He was also a serious boxer, so quick that in spite of his size he was hired as a lightweight sparring partner for heavyweight champions Jess Willard and Jack Dempsey, who liked his raw speed. Dempsey—the world heavyweight champion from 1919 to 1926, known as Uncle Jack in the family—would become Bobby’s lifelong business partner in oil and other investments. One of their better-known ventures was the 20,000-seat indoor arena in Tyler called the Oil Palace, which was eventually finished (on a slightly smaller scale) by Bobby’s oldest son. After Bobby’s death, his wife, known by the family as Mama Dot, who was as driven and as talented as her husband, took over the business and expanded it, drilling fifty new oil wells a year.

A 1930s family photo showing (from left) Bobby Manziel (Johnny’s great-grandfather), Mary Manziel (Bobby’s mother), an unknown man, Gloria Manziel, and former world heavyweight champ Jack Dempsey, who sparred with Bobby, became his business partner, and was known in the family as Uncle Jack.

A 1930s family photo showing (from left) Bobby Manziel (Johnny’s great-grandfather), Mary Manziel (Bobby’s mother), an unknown man, Gloria Manziel, and former world heavyweight champ Jack Dempsey, who sparred with Bobby, became his business partner, and was known in the family as Uncle Jack.

The next generation of Manziels were not only wealthy but just as competitive as their parents. Big Paul was a Golden Gloves boxing champion. He raced anything he could get his hands on, mostly cars and boats. He set a Mississippi state record on the Southern drag-boat circuit and won a national boat-racing championship in Oklahoma. Then there were the roosters. Big Paul and his brother Bobby Jr. loved cockfighting, a blood sport that was still legal at the time. They raised roosters on their own spacious ranches in Tyler and traveled all over the world to fight them and bet on them. Big Paul’s then-wife, Pat—Johnny’s grandmother—loved going to the fights. She too was athletic and played to win, especially when going against her nephews and nieces and even her own children, including Johnny’s father. “There was a lot of racing,” she told me. “We would race from the gate to the boathouse. I would beat them every time. We’d have races on Jet Skis, to see who could jump the highest wave. Or who could stay up longest on water skis. I never let them win, and when they did win, it really ticked me off.” Pat would later make a deal with Johnny’s entire Little League team: $20 for every home run they hit. She once paid out $80 in a single day, most of it to her grandson.

The competitive gene continued to work its way down. Johnny’s father grew up racing boats and cars with Big Paul. He played golf in high school; won a scholarship to Midwestern State University, in Wichita Falls; and is a scratch golfer today. He and Johnny’s mother, Michelle, who also played varsity golf, at Robert E. Lee High School in Tyler, have a closet full of amateur tournament trophies.

Johnny, three generations removed from his lightning-fisted, bantam-weight great-grandfather, turned out to be the most competitive Manziel of all. When he was young, his step-grandfather on his mother’s side, Jerry Loggins, who owns the oldest restaurant in Tyler, would pick him up after elementary school and take him fishing or golfing. No matter what the activity was, says Loggins, it was always a contest. “If I caught more fish than Johnny did, he would get very quiet, and when we got home, he would go to his room, and you wouldn’t see him. He just doesn’t like losing, at anything. Ever.”

When Johnny was in seventh grade, his parents moved from Tyler to Kerrville. It was a deliberate move away from the family enclave. “We love the family, but we needed to get away,” says Michelle. “In some ways it was too easy. I just wanted our kids to be treated as kids and not have that Manziel name over their heads. In Tyler it means you own a lot of property and have oil interests. Nobody in Kerrville knew about any of that, and we thought that was a good thing. We liked the idea of a fresh start.”

Kerrville also offered them business opportunities, which they needed. Though Big Paul and Pat were wealthy, they insisted that their kids make it on their own, with no financial assistance. Thus Johnny’s parents are, in the words of his uncle Harley Hooper, who owns a clothing store in College Station in addition to the one in Tyler, “entirely self-made. They have worked their butts off.” They are affluent but not rich, as they have sometimes been portrayed. Paul’s main line of work has been selling cars; today he is the general manager of a Honda dealership in Longview. Michelle sells real estate and also works in Hooper’s College Station store. In Tyler, they had built and sold houses as a side business. The opportunity to build houses in the booming Hill Country led them to Kerrville, which was how Johnny ended up at Tivy High School.

To many people, Manziel’s Heisman season seemed to come out of nowhere. These people, it must be said, did not live in the Hill Country or neighboring San Antonio near the end of the past decade. Those who did got their first look at Manziel’s abilities on the night of September 26, 2008, when the Fighting Antlers of Tivy High took on the Chargers of Boerne-Champion High. Manziel was a sophomore who had recently won the varsity quarterback job. The Chargers were undefeated, ranked fifth in the region, and had held their previous opponents to 13 points or less per game. To the amazement of the crowd, the slender, five-foot-ten-inch Manziel ripped through Boerne-Champion’s defense as though it did not exist. He threw for 232 yards and three touchdowns and rushed for another 143 yards in a 50–20 rout. In the third quarter he cut loose on a 69-yard touchdown run, only to have it called back by penalties that moved his team back 20 yards. On the next play he sprinted 89 yards for a touchdown.

Though he soon piled up record numbers—the likes of which had never been seen at Tivy High—and as a junior led his team to the state 4A semifinals, it was in his senior year that his performance went from merely phenomenal to otherworldly. That season he personally accounted for 5,276 yards of total offense and 75 touchdowns. He averaged 440 yards per game. He was third in the nation in total offense. He was named a Parade All-American and the National High School Coaches Association Senior Athlete of the Year. He put up these numbers even though in six blowout wins he barely played in the second half. He also did it with a team that, compared with many of its opponents, was almost ludicrously undersized, fielding 180-pound linemen against players who routinely outweighed them by 50 or more pounds.

Nowhere was Tivy’s size and talent disadvantage more apparent than in its games against 5A powerhouses Madison High, from San Antonio, and Steele High, from Cibolo, teams that were loaded with Division I–bound players. Against the area’s number-one-ranked Madison, Manziel, running Tivy’s trademark wide-open spread offense, put up even more-astonishing numbers than usual, completing 41 of a state-record 75 attempts for 503 yards and 4 touchdowns in a 39–34 victory. The following week Tivy took on eventual 5A state champion Steele, which featured All-American, All-State, and All-District players and one of the nation’s top running backs, Malcolm Brown (now a starter for the University of Texas). Before a screaming, delirious hometown crowd in Kerrville, Manziel dueled Brown, while Tivy’s undersized team played, as one of the players put it, “out of their shoes.” Brown lived up to the All-American hype, running for 354 yards and 4 touchdowns. Manziel, meanwhile, had one of the best nights in his career, throwing for 423 yards and 6 touchdowns and rushing for 129 yards and another 2 touchdowns in a thrilling 54–45 victory.

But perhaps Manziel’s greatest achievement as a senior came in two heartbreaking losses—Tivy’s only ones that year—to Lake Travis High School, one of the top high school football teams in the nation, which was in the middle of its unprecedented run of five straight 4A state championships. In two epic battles, Manziel and Tivy scored more points than any team had ever scored on Travis during its run, losing 37–33 in a non-district game and 48–42 in the state playoffs. The latter was Manziel’s heroic, bittersweet farewell to Tivy High. “We played against tremendous odds through Johnny’s whole career at Tivy,” says Julius “Juju” Scott, who was the offensive coordinator for Tivy during Manziel’s years there. “People think he played a miraculous game against Alabama, but in Kerrville I saw him do that with a lot less talent around him. Nobody scored that many points on Travis. Beating the Steele Knights? Come on. They’ve got sixteen Division I players. We had one. It shouldn’t be close.”

How did Manziel and his fellow Antlers pull this off? He was a singularly talented quarterback, of course, but the team’s success was also due, more than a little, to love and brotherhood. At weekly devotionals, the entire team, with several coaches, would pack into one room at a local church and shut the door. Though the meetings were optional, everyone attended. “At the beginning of the meeting, they would show a highlight video of the week before,” says Manziel, “and after that, anybody could say anything, and it would never, ever get brought out of that room. Sometimes I would tell a funny story, make people laugh. Sometimes I would come up and have a Bible verse to read—David and Goliath, just whatever it was. Afterward Coach Scott would say a prayer, and then you would hug every person in the room before you left the building, coaches too. There was not a person there that wouldn’t hug any guy on that team. It was awesome. So rare. People wonder why Tivy was so good. We were all brothers. We loved each other.”

As a leader, Manziel could be hard on his teammates, but he had a softer touch when it came to the weaker players. During the team’s final home game, he told Scott that he wanted to make sure that Robert Martinez, a popular senior receiver who had never played, scored a touchdown. Scott approved and put Martinez on the field, and on the next play Manziel deliberately slid down at the 1-yard line to set it up. On the following play he lined up in the shotgun, gave the ball to Martinez, then grabbed him by the jersey and half-carried him into the end zone. Martinez, who was hoisted onto his teammates’ shoulders, was thrilled. After the game, his mother thanked Manziel with tears in her eyes. It is one of Manziel’s best high school memories.

In his three years as a varsity quarterback, Manziel had become a certified Hill Country legend. People drove hundreds of miles to see him. He packed stadiums all over the district. Kerrville would come to an abrupt standstill during every home game. His wild, off-the-cuff plays, often drawn in the dirt or the air by Scott in the moments before the snap, made him a YouTube hero, which drew people from even greater distances. In spite of all this, he managed to lead the normal life of a Kerrville kid. “We were just constantly outdoors,” says Manziel’s close friend Nate Fitch (who would follow him to A&M and later become his personal assistant). “That’s what you do here. Everybody hunts and fishes, and sports occupied the time between.”

Manziel also found time to get into a little trouble. One night he went to Walmart to buy a phone charger. While he was there a security guard smelled alcohol on his breath and called the police, and Manziel was taken to jail. His father, furious at him, refused to pay his fine and even suggested that the judge increase his community service hours from ten to twenty. Paul also sold the new car he had given Johnny on the condition that he stay away from alcohol. In its place he gave his son an old, rattletrap pickup truck to drive to school.

“Johnny Manziel is a red-blooded American young man,” says Scott, with whom Manziel still has a close relationship. “He is not superhuman, he is not a saint, he does not have a halo. He is subject to the temptations everyone else is. But he is a great person. He has a genuine love for his teammates and coaches. I have never spoken to him on the phone when he didn’t end the conversation saying, ‘I love you, Coach.’ He has never not said it.”

Manziel may not have been superhuman, but his statistics very nearly were, and they ought to have guaranteed him a spot on at least one of the two teams he had dreamed about playing for: UT and, later, TCU. But neither school, as it turned out, offered him a scholarship. TCU showed no interest at all; UT considered him for an athletic scholarship, but not as quarterback. Baylor, another school Manziel could envision himself at, did end up offering him a scholarship but also did not want him as a quarterback.

It wasn’t for lack of familiarity. No schools in the country had gotten a better look at Manziel. “After sophomore year I would load him up in the car, and we would go to these camps,” says Michelle. “We went to Baylor junior days, and we went to UT every year. At UT they had already made their selections—here is McCoy’s brother warming up over here, and they had the others over there. We were with the others. Johnny also loved TCU, and we did somersaults for them. We went to their camps; Paul would go talk to Coach [Gary] Patterson. But they never moved.”

“I would go to every camp, and I tried so hard,” Manziel recalls. “We would just bounce around the state, but we never got an offer.” A&M, meanwhile, seemed, in the early going, just as uninterested as TCU and UT. The rap on Manziel was predictable. At six-foot-one, he was too small. He was a running quarterback in a world that favored pocket passers. Nobody seemed to have noticed that, with Tivy’s flyweight offensive line going against the likes of Steele, Lake Travis, and Madison, he’d had no choice but to flee the pocket. “If he stays in the pocket, he gets killed,” Scott said at the time.

It has been widely written that Manziel was a lightly recruited player. That is not true. Though UT and TCU never offered him anything, and A&M demurred, by the summer of 2010 he had received bids from Iowa State, Colorado State, Louisiana Tech, Tulsa, Wyoming, the University of Texas at San Antonio, Rice, Baylor, Stanford, and Oregon. The latter two represented the sort of football programs he was looking for, and they were the cream of the Pac-12. In June he committed to Oregon, one of the best teams in the nation with one of the best coaches. He was ecstatic. It wasn’t a Texas school, as he and his parents had wanted so badly, but it was a great offer. He was going to the Northwest.

Then something happened—a seemingly small shift in the currents of destiny that would change Johnny Manziel’s life as well as the future of Texas A&M. In early September 2010, a highly regarded quarterback from Arizona named Brett Hundley, who had been considering both UCLA and A&M, announced his commitment to UCLA. This was very late in the recruiting game, and it meant, among other things, that A&M suddenly needed another quarterback for its roster. Though Aggie head coach Mike Sherman had shown only lukewarm interest in Manziel before, all that now changed. Spurred by offensive coach Tom Rossley, who had seen Manziel play and believed that he might be the next big thing, Sherman soon made an offer. Manziel, whose heart had always been in Texas, accepted and then made what he says was a “very difficult” phone call to Oregon to “de-commit.”

His debut at A&M fell far short of glorious. In the fall of 2011, the Aggies had an excellent starting quarterback named Ryan Tannehill, who would be a first-round NFL draft pick in the spring. They had a talented backup in Jameill Showers. They were running a pro-style offense that had virtually nothing in common with Tivy’s wide-open, brilliantly improvisational spread. As Manziel puts it, “I was just the kid in the back of the room. They would tell me to go turn the lights on.”

So Manziel was relegated to a role as quarterback on A&M’s “scout team,” where his job was to mimic opponents’ offenses during team scrimmages. A scout quarterback is generally supposed to pass the ball where the defensive coordinator tells him to. On occasion this involves throwing an interception or purposefully botching a play, but Manziel, with his almost feral, fast-twitch reflexes, sometimes failed to do that. “The coach used to get so mad,” Manziel says, laughing. “They would yell, ‘F—ing throw it to the same guy again.’ Whatever. I am not made to throw picks intentionally. I am not going to do that.”

Manziel, as the coaches were discovering, is a polite young man most of the time, but on the field, he is almost outrageously cocky. He always believes he is the best player out there and that no one can beat him. In practice before the Baylor game, he was tasked with mimicking the fleet, elusive Robert Griffin III, an assignment he turned out to be devastatingly good at. “I remember getting frustrated at our defense, because we couldn’t tackle him,” A&M’s former defensive coordinator Tim DeRuyter told a sports blog. “[I was] yelling at our guys, saying, ‘If you can’t tackle this little freshman, how in the world are we going to tackle RG3?’ And then after the game, our guys are like, ‘Coach, I’m telling you, that guy was harder to tackle during the week than RG3 was.’ I think RG3 had about fifty yards against us, running the football. Manziel probably had six hundred during the week.” But Manziel would pay a price for his arrogance. Coaches soon ordered him to remove his special black jersey, which signals the defense not to pulverize the quarterback. “They got sick of chasing me, so they put me in a normal offensive jersey where they could hit me, and they would just pop me so hard,” says Manziel. “They would light me up for a couple of weeks.”

For Manziel, who labored week after week to fit in with a team that he was not really a part of, the world was not a happy place. His future with Sherman, who was running a conservative offense, was gravely in doubt. Many thought he had no future at all. He was stuck; the road that had led him to A&M now appeared to be a dead end.

While Manziel struggled to adapt to his new obscurity, profound changes were under way at Texas A&M. It could be said, in fact, that more than forty years of tinkering with the very nature of the university were finally coming to a crescendo. Since the sixties, when the all-male military school first opened its doors to women and non-military students, A&M had been making a steady ascent in the academic world to become a top research institution. In 1997 it opened a presidential library, and in 2001 it was accepted into the Association of American Universities, the nation’s most prestigious club of research universities and institutions. Last year, the university drew $700 million in outside funding, acquired a law school in Fort Worth, announced a federal contract that will make it one of the major vaccine-producing hubs in the world (generating six thousand jobs and an expected $41 billion over twenty years), and initiated a plan to increase enrollment to 25,000 at its eighth-ranked engineering school, which is already the nation’s third-largest undergraduate program.

Yet throughout much of its growth, the university had remained convinced that it had an identity problem, that too many people still saw it as a hidebound regional school far removed from the wealth, power, and sophistication of its longtime archrival, the University of Texas. Although the public seemed to understand that A&M no longer consisted of just the Corps of Cadets (now only 4 percent of the student body), it had not fully embraced the university’s transformation. Thus, A&M embarked on a major campaign to refashion its image before the larger world. This was no easy task. A&M was already so well defined that it was going to take more than slogans and advertisements to change public opinion.

Hence the university’s dramatic decision to join the Southeastern Conference. (For those interested in tracking the alignments of fate, this took effect on July 1, 2012, the day after Manziel was released from jail.) The move accomplished two things: it uncoupled A&M from UT, and it placed the university on a bigger national stage. The football team, the most powerful marketing tool any major university possesses, would now be playing the best teams in the country, in the most prime television slots. But for many sports fans, posting furiously on hundreds of websites, it was nothing short of a catastrophe. The Aggies were sure to be pounded into paste by a brutal lineup of ranked opponents. There was a sense, moreover, that by withdrawing from the rivalry with UT, A&M had destroyed a cultural tradition. State lawmakers discussed passing legislation to counteract the move. And among the jilted members of the Big 12, A&M was seen as sulky, petulant, and vengeful, unreasonably angry over such perceived offenses as UT’s launch of the Longhorn Network. “The strong message was ‘Why are you messing it up?’ ” says A&M president R. Bowen Loftin, who was the driving force behind the move. “ ‘Why not let things be, because historically, you belong where you are right now?’ ”

But A&M did not want to stay where it belonged. Joining the SEC was a deliberate step away from the university’s past, an outlandish bet that amounted to going all in on its future. “It allowed us to shed the stereotypes that are perpetuated here in Texas and open up the borders of the state, not only to the Southeast but to the rest of the country,” says Jason Cook, A&M’s senior associate athletics director for external affairs (and former vice president for marketing and communications), one of the architects of the conference change. “The move was a manifestation of our growth. It said that we have reached a point where we can stand on our own and be recognized nationally.”

A lot of that, of course, had to do with getting away from UT. When asked recently for a statement about how the move to the SEC had affected relations with the Aggies’ old nemesis, Loftin said simply, “I don’t have to make [that statement] anymore. It’s not relevant to us anymore. That’s the whole point. It’s not an important issue.” In recorded history, no Aggie in any position of authority had ever uttered such words.

And yet the potential for disaster was very real. More than forty years of striving had found its final expression in one highly risky gambit. The Aggie brass appeared confident, talking about the long-term benefits of the move to the SEC, but Loftin, Cook, and many others in College Station—including Chancellor John Sharp and Athletic Director Eric Hyman—were all too aware of what the reaction would be if the football team was humiliated in its new league.

Texas A&M chancellor John Sharp, on whose watch the university left the Big 12 for the SEC, photographed in his office on May 31, 2013.

Texas A&M chancellor John Sharp, on whose watch the university left the Big 12 for the SEC, photographed in his office on May 31, 2013.

Into all this galloping transformation and high-wire marketing came Manziel and new head coach Kevin Sumlin, who was himself a significant symbol of change. In December 2011, after a dismal football season, Sherman had been fired; Sumlin, who took over that same month, was the first African American head football coach in A&M history. And critically for Manziel, he was the designer of a wide-open offense the likes of which the university had never fielded. That fall, Manziel took his first snap as Sumlin’s quarterback, and nine weeks later, nearly 10 million Americans watched A&M beat Alabama on national television. That week everyone in the country, it seemed, was talking about Texas A&M. And for Aggies looking to establish a new identity, that was exactly what the school needed. “What Johnny and the team did was make folks look at us,” Sharp says. “We’re the number one research university in Texas and the Southwest, but nobody was telling the story.”

The importance of Kevin Sumlin in the legend of Johnny Football cannot be overstated. Before becoming the head coach at the University of Houston, Sumlin had excelled as offensive coordinator at A&M, under R. C. Slocum in 2002, and shared the title at Oklahoma, under Bob Stoops in 2006 and 2007. Slocum had given him the job after the team’s third lackluster game that season. “I put Kevin in charge of the offense, and it was like you flipped a switch,” says Slocum, now a special adviser to A&M’s president. “It went immediately from dark to light. They were the same players, but it just looked completely different.” Sumlin’s University of Houston team ran a high-speed, no-huddle spread offense built around a play-making quarterback, an approach the coach took with him to A&M and which seemed tailor-made for Manziel’s skills. “I saw some of the new plays and I just thought, ‘I have done this for four years,’ ” says Manziel. “ ‘I know the terminology, I know the stuff. It’s a little different, but I know it.’ And it was just like a blessing.”

But Manziel, now a redshirt freshman and full member of the team, may have been overly excited. During spring football in 2012, he seemed to be trying too hard, going for a big play every time he had his hands on the ball. For the first time in his life, Manziel, normally a deadly accurate passer, had trouble hitting his targets. “It was like I had the yips or the shanks,” he recalls, referring to problems that afflict golfers. His parents were horrified. “He was just terrible,” says Paul. “He was awful. We didn’t know what was wrong, but I could have made better passes than some of the ones I saw him throw.” A&M’s offensive coordinator, Kliff Kingsbury, now the head coach at Texas Tech, was worried about him too.

“I knew in the spring that he was not focused,” says Kingsbury, who happens to be from New Braunfels and knew all about the Manziel legend. “I remember talking to him, and he was like, ‘Coach, I am not being myself.’ He wasn’t playing very well. And then after spring practice ended, I was on vacation in Cabo when someone emailed me a picture of the famous mug shot with his shirt off, and I was like, ‘Oh my God, here we go.’ ”

But although no one could have possibly guessed it at the time, that mug shot marked the beginning of Manziel’s five-month run to the Heisman. In early July, immediately after he was released from jail, Sumlin sat him down for a long meeting. The message was clear: if Manziel did anything like that again, he was done. “They came down hard on him,” says Michelle. Sumlin gave him a checklist, things he would need to do through the end of the summer and into the season to get back in the good graces of the football team. These included sessions with a counselor and community service, plus extra running and other physical exercises. Partying and drinking beer were, by agreement, strictly off limits.

“Many of those things have not been made public,” says Sumlin. “But that’s a lot of what went into his transformation. The things he had to go through—those are life-changing experiences. Sometimes you need to be at your lowest point for things to hit you in the face.”

Football coach Kevin Sumlin at an August press conference addressing reports of Manziel’s alleged NCAA violation.

Football coach Kevin Sumlin at an August press conference addressing reports of Manziel’s alleged NCAA violation.

The team reconvened on August 3. “He was a different player,” says Kingsbury. “He was on a mission.” Still, that only meant that he was probably—as the media clearly believed—the second-best quarterback on the squad, if not a notch lower than that. And yet that was not even his biggest problem.

As the events of this summer have made abundantly clear, Manziel has a special ability for courting disaster. Over and over again, he finds himself having to scramble out of a jam. This summer’s training camp drama marked the second year in a row that he has gone through fall practice not knowing if he would even be eligible to play. People within the program could be forgiven for thinking, “Haven’t we seen this movie before?”

In 2012 the trouble originated with “the incident.” Though a lawyer hired by his family had managed to defer his court appearance on charges stemming from the June arrest, as training camp began, A&M weighed in with its own disciplinary review. The university does not conduct such reviews for every off-campus student offense, but in the words of Anne Reber, A&M’s dean of student life, “When things hit the newspaper, TV, or radio and it comes to our attention, now you are looking at the university’s reputation per se, and so we look at that and determine whether we need to reach out and touch those students.” On August 6, three days after fall football camp started, Manziel came before a panel called Student Conduct Services, which punished him with a sanction known as conduct probation. This meant, incredibly, that he could not play football that fall. “Johnny called and said, ‘Mom, you are not going to believe this,’ ” recalls Michelle. “ ‘I got conduct probation. I can’t play. I can’t play at all.’ ”

His only hope was an appeal. By university policy, he had five business days to make it. Two days later, Manziel, his parents, and his coaches met to develop a strategy. Sumlin and Kingsbury wrote letters of support. “We were all in this together,” says Michelle. “It was a total team effort.” The appeal was filed with Reber’s office on August 10. Manziel, meanwhile, continued to practice with the team. He was playing well, even though he knew that it could all come to naught. If the sanction stood, his mother told me, they were planning to transfer him to a junior college.

Then Reber handed down her decision: Manziel’s sanction would be modified. He would have to perform twenty additional hours of community service and complete some extra classwork. But he was no longer on probation. Combined with Sumlin’s discipline, this still amounted to a fairly large punishment for a relatively small offense, but none of that mattered. Reber’s decision, which was dated August 14, meant he could play. One day later Sumlin named Manziel Texas A&M’s starting quarterback.

It was an extraordinary move. Manziel had performed poorly in the spring. He had been outplayed by Jameill Showers in the Maroon and White Spring Football Game. He had then gotten himself arrested and nearly been banned from playing football for the season. But Sumlin had somehow seen through all that. He made it clear, moreover, that there was going to be no rotation of quarterbacks. This was not a “we’ll see how it goes” decision. It was Manziel’s team now. “He’s the starter,” declared Sumlin that fall. “He’s going to play.”

Reviewing the chain of events that led to Manziel’s and Texas A&M’s 2012 football season, there is a point when you stop believing in coincidences. It all seems foreordained: how TCU and UT and Baylor passed on him, how A&M would have too but for the defection of a high school quarterback from Arizona. How he turned down a shot at one of the nation’s greatest football programs for a mediocre 7-6 team that was setting up to be dead meat in the SEC. How Mike Sherman, who probably would not have played him, was fired, and how Kevin Sumlin, a dream coach with a dream offense, got the job. How Manziel’s arrest led not to wrack and ruin but to a partnership with that dream coach. How a ruling by a Texas A&M dean saved his football career at the eleventh hour. How, before all this, a physics professor turned university president had had the gumption to finally push through the university’s move to the SEC, without which there would never have been an Alabama game, without which there would never have been a television announcer shouting, “Four-man Alabama rush . . . Got him! Oh, no! They didn’t!! Oh my GRACIOUS!! HOW ABOUT THAT?!?” as Manziel stumbled and fumbled and somehow managed to escape the rush and hang on to the ball and find Ryan Swope in the end zone and bring the entire country to its feet. Manziel and his family believe that what happened was God’s plan. I have not heard a better explanation.

But the Lord giveth and the Lord taketh away. No sooner had Manziel demolished the Sooner secondary at the Cotton Bowl Classic on January 4 and commenced his off-season than the problems started. The weekend after the game, pictures surfaced of Manziel holding a bottle of champagne in a Dallas club and a wad of cash in an Oklahoma casino. Both incidents were fully aboveboard—his parents were with him at the club, and it is legal for eighteen-year-olds to gamble in Oklahoma (Manziel himself had Instagrammed the photo). Nonetheless, the Internet exploded with wild speculation that he was already headed for a fall. It was the first indication of Manziel’s signal ability to attract publicity, much of it negative and based on sketchy, unsourced, or rumor-driven accounts. Partly this is due to the fact that after the Heisman, Manziel became famous in a way that no college athlete had ever been before. Think about it: when Tim Tebow won the award, in 2007, social media was in its infancy. When RG3 won it, in 2011, he was a senior and already on his way to the NFL. Manziel, the only freshman ever to win the Heisman, lives in a different world. Through the instant, globe-spanning magic of Twitter, Instagram, YouTube, Facebook, and the blogosphere, his every public move—and I mean every—is chronicled. As he quickly learned, if he went out to dinner with a girl, people in New York and even Tokyo would know where he was and who he was with before he even left the restaurant.

Anywhere he went in College Station, he was immediately enclosed in a sea of students, all wanting photographs and autographs. When he went out to eat with his family, the sudden influx of fans in the restaurant threatened to disrupt the kitchen’s entire meal service. When he and his friend Mike Evans, a wide receiver, went to the rec center to play a pickup basketball game, they drew a crowd of a thousand. Manziel spent two hours signing and photo op–ing.

Almost overnight, the kid had become one of the most visible celebrities in the country. He went to the Super Bowl, Mardi Gras, the NBA All-Star Game. He hung out with LeBron James (who wanted his photo taken with Johnny Football), Justin Timberlake and Jessica Biel, the Duck Dynasty guys, and various country music stars. He appeared on Letterman and Leno, threw out the first pitch at Rangers and Padres games, and traveled to Toronto to spend time with his favorite musician, Drake, who Manziel says treated him “like family, like a brother.”

Throughout it all there was a steady drumbeat of criticism. Many people simply didn’t approve of Manziel’s behavior. Thanks to his family’s money, he could afford things that most college kids couldn’t, and he was not inclined to deprive himself of, well, anything. His dad bought him a Mercedes C-Class. He sat courtside at basketball games. He partied in Cabo San Lucas with bikini-clad college students. When his family sued some people who were selling Johnny Football merchandise for copyright infringement, he was perceived as greedy. When someone faked a Tweet from him saying a nasty thing about an Ohio State basketball player, the entire Buckeye Nation came down on him.

This summer he was in the news almost every day. The first incident was his own fault. Angry over a parking ticket he had received in College Station, on June 16 he sent a tweet to his 300,000-plus followers that said, without any reference to the ticket, “Bullshit like tonight is a reason why I can’t wait to leave College Station . . . whenever it may be.” Though he immediately deleted the tweet and followed with the penitent “Don’t ever forget that I love A&M, but walk a day in my shoes,” he set off yet another viral round of tongue wagging and obloquy. On July 13 he roared into the news again, this time for not showing up to meetings and training sessions at a quarterback camp in Louisiana run by Archie Manning and his sons. The subtext was the usual one: he had been photographed at a bar the night before with Alabama quarterback A. J. McCarron, thus his critics gleefully concluded that he had been out drinking again. He denied it, saying that he had missed the meetings because his cellphone had died and the alarm hadn’t sounded. The media exploded further when McCarron, in interviews that week, appeared to distance himself from Manziel. Though Peyton Manning defended Manziel and McCarron later tweeted that “people have lost their mind if they think I dissed JM in any way,” the damage had been done. People who believed he was an out-of-control party hound would see more proof when, on July 15, Manziel pleaded guilty to a single charge of failing to properly identify himself in the June 2012 drinking and fighting incident in College Station. Though the charges of disorderly conduct and carrying fake identification were dropped and he was let off with a $2,000 fine and no additional jail time, news of the plea was devoured on sports talk radio and message boards.

What to make of all this? Though a certain segment of the Internet now seems to regard Manziel as an irredeemable villain, when you get right down to it, his drinking and fighting and poor social-media judgment are little more than the work of a defensibly cocky, impulsive twenty-year-old with a maverick streak. It’s the same quality that makes him such a terror on the football field, and it is essentially a hereditary trait. Earlier in the summer, I’d spent an afternoon at his grandmother Pat’s attractive, memorabilia-filled townhome in Tyler. Johnny and two of his friends were out on the lake with Big Paul, messing around in his speed boat, a heavily tricked-out machine with twin supercharged Corvette engines that Manziel’s father estimates has cost Big Paul half a million dollars. As we waited, Pat told me a story about beating her children at a game called Krazy Bee Rummy back in the old days. Suddenly the boys blew in from the garage.

“Well, I can add one to the bucket list,” Manziel said. “I always wanted to go more than one hundred miles an hour in a boat. It was awesome.” His friends Colton and Nate nodded their heads in agreement. “We hit 102,” Manziel continued. “It blew Nate’s contacts out of his eyes.”

In most families, hanging out with one’s grandfather does not entail attempts to set speed records. But these are Manziels. As the boys wolfed down some reheated Chinese food, they talked about the boat ride and their plans to drive to Dallas that night to meet a new roommate of Manziel’s and attend a country music concert. Manziel, as usual, was a package of fast-moving, nervous energy. “I have trouble keeping up with him,” said Nate at one point. “He doesn’t sleep much.” In fact, you don’t have to be around Manziel long to see that he’s hyperactive—he is restless and moves constantly. “He needs to be kept busy,” says his mother. He is also, in both his personal life and on the football field, a fundamentally improvisational person. On some level an immoderate midnight tweet may be the equivalent of a 50-yard run off a busted pass play. It is this unpredictable streak, in fact, that makes him so utterly compelling, both on and off the field.

Which is why the autographs-for-money allegations have at least the ring of truth. Would Manziel do something so ignorant and self-destructive that it could, in the worst-case scenario, implode the Aggies’ season and jeopardize his own future NFL career? Sure. This is Johnny Football we’re talking about. He still hasn’t mastered all his powers, and there’s really no telling what might happen with him, ever. He could beat Alabama again, this time at Kyle Field, on his way to winning a national championship. Or he could miss that game entirely. Who knows?

A fair number of fans are already disposed to view the allegations as yet one more example of the outrageousness of the NCAA’s amateurism rules (see Behind the Lines). A system in which Manziel—who has been worth so much to so many commercial and academic institutions—is not allowed to take a relatively small amount of money for himself in exchange for signing his autograph appears increasingly unfair to a growing number of fans. Could the kid trigger a revolution in college sports? Last year he transformed the image of Texas A&M. This year, what might he do to the NCAA? As the season begins, the question hovering over Johnny F—ing Football is the same question that’s always hovering over Johnny F—ing Football: What the hell is the kid going to do next?