Sometimes on the courthouse square in Archer City it’s easy to feel like the only human creature in town. But on a recent Friday afternoon, the place was packed with sleek Mercedes-Benzes and Lexuses that occupied spots usually empty or taken by a few pickups. The drivers of these cars swarmed the square and loaded boxes of books into trunks and backseats. Trucks hauling rig equipment on trailers slowed and stopped for people crossing the street.

Several hundred outsiders had descended on the town, a tiny ranching community in the northern part of the state, for a huge book auction hosted by Larry McMurtry. He planned to sell 300,000 of the 450,000 books he had brought here since returning to his hometown in the late 1980s.

“Nothing has ever happened like this in Archer City. I’ve never seen this many people parked here,” said McMurtry, 76, the town’s most famous resident and arguably the state’s most famous living author. “I wondered whether it was wise to bring a lot of citified Northerners into the heart of the heat. The books, I think, will make it worth it.”

His books, a handpicked collection sold out of four stores he named Booked Up, defined Archer City for decades. McMurtry opened the first shop in 1987, at a time when his fame soared from the success of Lonesome Dove and Archer City reeled from the collapse of oil prices. During the next ten years, McMurtry bought up vacant storefronts on the square and filled them with hundreds of thousands of books. He dreamed of creating a book town, not unlike Hay-on-Wye, a village in Wales that started with one store and eventually attracted dozens of booksellers. He took out ads in bibliophile magazines. “Miraculous birth!” they read. “Visit the newly born book town of Archer City, Texas, and help the endless migration of good books continue.” A shuttered hotel was renovated and reopened, and the town’s original hospital was turned into a bed and breakfast, both to accommodate the carloads of buyers and McMurtry fans who made the long journey to Archer City.

For those outsiders, the attraction was almost mythic. Brandon Kennedy, who works in the modern and contemporary art department at Heritage Auctions in Dallas, has traveled to McMurtry’s bookstores repeatedly over the last thirteen years. “Driving from a metro area, you witness the city and suburbs going away and then your mental state starts to echo the landscape and you get a clear head to approach what’s around you,” Kennedy said. “That’s what was so great about having these bookstores in town. “

But the book town stalled. Only one other shop opened and it’s gone. The hotel has been for sale for years, and now the bed and breakfast is on the market too. “The Last Book Sale,” as McMurtry billed the auction, appeared to mark the end of his book town experiment. He described the three-day event as the “sensible” thing to do for a man near the end of life with heirs who have no interest in running book stores. “It’s bittersweet,” said Faye Kesey, the widow of the author Ken Kesey who married McMurtry last year. “It’s like anything at the end of life. Kind of like leaving your family behind.”

The sale also leaves Archer City, population 1,834, at a crossroads. “We’re like a lot of small towns struggling, and the only way to hold water is to get outside people coming in,” said Rick Jones, an Archer City councilman. For years, even as the hopes for a book town fizzled, visitors kept coming to McMurtry’s stores and bringing a valuable infusion of tourist dollars.

“Every little bit helps,” said Cliff Byrd, 71, who has lived in town his whole life. “The oil business is gone, most of the wells have dried up. The ranching business is gone. A few ranchers are handing down land through families, but they don’t contribute a lot to the economy. They used to buy vehicles, but there’s no longer a dealership here. I see no new business.”

Matt McLemore, McMurtry’s nephew who was raised in Archer City and now sells ranch land out of an office on the square, added, “The bookstores brought culture that we wouldn’t have had here.”

The auction signifies a palpable loss for Kennedy, who drove the 140 miles from Dallas to witness the sale. “I found myself not wanting to think about the stores that’ll be gone, because you won’t have a chance to revisit them,” he said. “It’s like limbs being cut off from the body.”

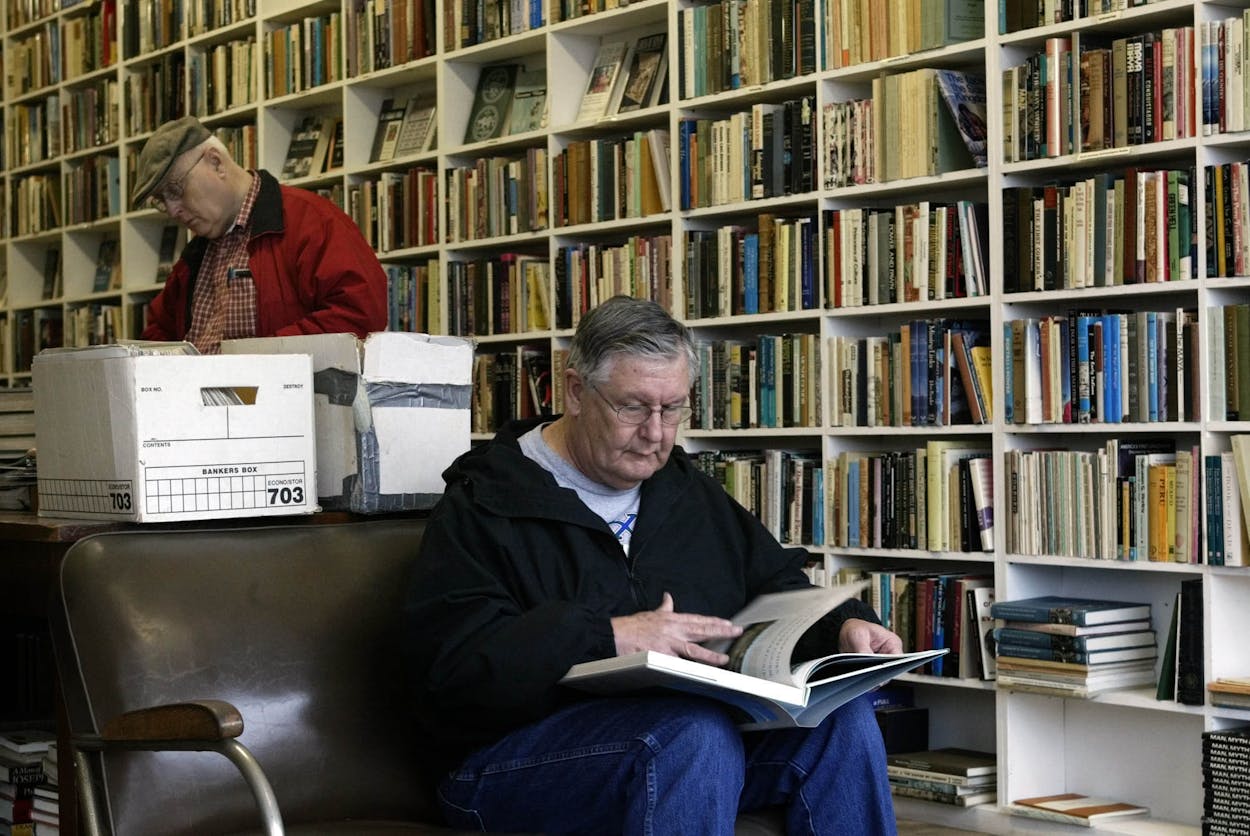

The redemption for McMurtry, and perhaps for the town, is his decision to keep Booked Up No. 1 open indefinitely. During the auction, McMurtry, who made $200,000 from the sale, mostly stayed away from the bidding area. He spent the rest of his time inside the one store that will remain, surrounded by the inventory that won’t leave town, sitting in a chair and talking to the people who came to see him. On Thursday, the day before the auction started, McMurtry sold more out of No. 1 than he ever had, and on Friday, the store was filled again with people browsing. A small gap on a shelf caused a few books to fall sideways, and McMurtry glanced at them. “I don’t like it when books lean,” he said.

By winter, after all the books are shipped to their new owners, McMurtry’s other three stores will sit vacant, and his son will try to sell the buildings. But McMurtry thinks the town will survive in a different form. “It’s got some pretty good antique stores now,” he said. “I think it will become an antique town.”

That’s difficult to imagine because, as famed author Susan Sontag once remarked during a visit to Archer City, the town seemed to be McMurtry’s own theme park. It started in 1971 when the Royal Theater, a cornerstone of the town’s square, was immortalized on a movie poster for The Last Picture Show. The Academy Award winning film, adapted from McMurtry’s novel of the same name, examines the loss of innocence in a fictional Texas ranching town, where the movie theater on the square, the town’s only connection to the outside world, permanently closes. The real Royal Theater in the real Archer City had closed too, after a fire nearly destroyed it.

It was at the Royal, which reopened in 2000, where McMurtry kicked off his book auction with a screening of The Last Picture Show. He shuffled up to the front of the theater and told the people in attendance how the otherwise bleak and depressing story about a dying town ended with moments of redemption. “You’ll see it [at the end of the movie],” McMurtry said. “A reprise of all the characters at their happiest moments.” The book buyers who came here from around the country to leave with loads of McMurtry’s stock, which he spent decades putting together, volume by volume, had come to see that end.

- More About:

- Books

- Larry McMurtry