We’re sitting alone in his bus, me and Willie, drinking coffee and sharing a smoke, two geezers talking about how it feels to approach age 65, commiserating about the predictable decline of kidneys, eyesight, knee joints, rotator cuffs, and sexual appetites. We agree that when dealing with life’s vagaries—the hits, misses, insights, and sorrows—attitude is everything. “However you want things to be,” Willie assures me, “create them in your own mind, and they’ll be that way.”

The miles are mapped on his face and crusted in his voice, which seems less melodic by daylight. Willie traveled all day yesterday, Thanksgiving Day, 1997, arriving in Las Vegas from the Bahamas just before show time. When he was in the Bahamas in 1978, I remind him, they threw him in jail for smoking pot and then banished him from the island for life. So they did, Willie recalls with a nod. He was so happy to be free of that damned jail he jumped off a curb and broke his foot. The following night, his foot in a cast, he celebrated again by firing up an Austin Torpedo on the roof of President Jimmy Carter’s White House: “That was an incredible moment, sitting there watching all the lights. I wasn’t aware until then that all roads led to the Capitol, that it was the center of the world.” Also the safest spot in America to smoke a joint, he adds. Willie credits God and the hemp plant for much of his good fortune and openly advocates both at every opportunity. Without encouragement he begins to list the consumer items produced by the lowly plant—shirts, shorts, granola bars, paper products, motor fuel, not to mention extremely enlightening smoke. “Did you realize the first draft of our Constitution was written on hemp paper?” he marvels.

From the window of the bus we can see the afternoon players drifting through the front entrance of the Orleans Hotel and Casino. Though management has reserved a suite for Willie in the hotel, by long habit he sleeps aboard his bus, venturing out only to play golf or make it onstage in time for the first note of “Whiskey River,” his traditional opening number. Willie says that inside his head is a network of communication outlets, that he has a mental tape recorder that starts with “Whiskey River” and lasts two and a half hours—the time needed to complete a concert. He also receives messages from angels and archangels and several bands of broadcast signals, some in languages unknown to the human race.

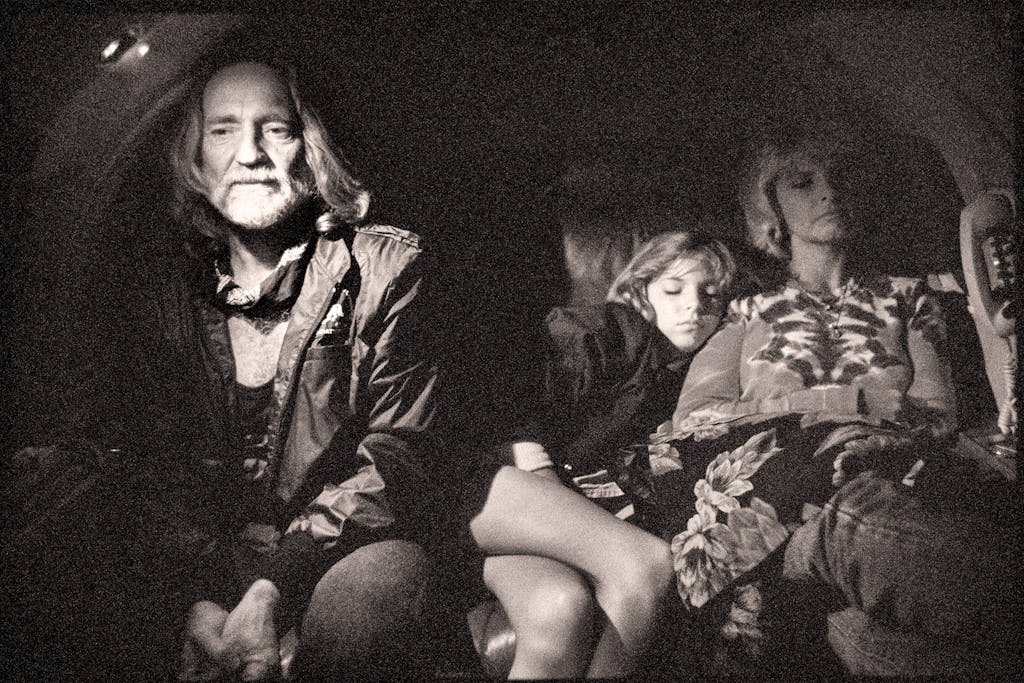

This bus, the Honeysuckle Rose, is Willie’s home, office, and sanctuary, not only on the road but also at Willie World (his compound outside Austin that features a house, a recording studio, a golf course, and a western film set). The bus is the one place he truly feels comfortable. It’s as well equipped as any hotel, with multiple TV sets, a state-of-the-art stereo and sound system, kitchen, toilets, showers, and beds. Willie’s private compartment at the rear is as cozy and as densely packed as a Gypsy’s knapsack. One of Willie’s old aunts once confided to writer-producer Bill Wittliff, “That Willie, he can pack a trailer faster than anyone I ever saw.” On his king-size bed lie three guitars, and surrounding it are Native American paintings, beaded necklaces, and breastplates; a giant American flag; photographs of his two youngest sons, Lukas and Micah (by his fourth and current wife, Annie); a jump rope; some dumbbells; and a speed bag anchored to a swivel above the door. Willie’s elder sister, Bobbie Nelson, and his daughter Lana also travel on the Honeysuckle Rose. Members of the band and crew ride in two additional buses and a truck that make up Willie’s relentless caravan.

“I don’t like to be a hermit, but I’m better off staying out here by myself,” Willie explains, taking a drag and passing the smoke across the table. “El Nino,” a song from his new Christmas album, plays in the background. “Too many temptations. In the old days we’d stay in town after a gig and start drinking and chasing women, and some of the band would end up in jail or divorced. That’s when I started leaving right after a gig, driving all night just to get out of town. If it wasn’t for the bus and this weed, I’d be at the bar right now, doing serious harm to myself.”

For a man who’ll be eligible for Medicare on April 30, Willie appears fit, trim, content, and comfortably weathered, a man who has not only transcended his wounds and scars but also made them part of his act. In his unique American Gothic way, he appears semi-elegant, a country squire in an orange sweatshirt, jeans, and running shoes, his hair neatly braided, his eyes crackling with good humor. He looks ready to run with the hounds. Willie exercises daily, jogging, stretching, jumping rope. He can make the speed bag rattle like a snare drum. A few weeks earlier he went three rounds with former heavyweight Tex Cobb, and he is about to get his brown belt in tae kwon do. Onstage the previous night, without warning, Willie kicked a microphone off a stand higher than his head. This is a regular part of the show, and his audience roared its approval. How many geezers can high-kick like a majorette?

As we talk, Willie squeezes a rubber ball, releasing nervous energy. “I have so much energy that it gets to be a problem,” he says. “I don’t smoke weed to get high; I smoke it to take the edge off, to level out, so I’m not out there like a turkey sticking his head into everything.” Though this natural energy is part of his creative process, it must obey the laws of physics: the action of whiskey, women, music, and life on the road eventually produces the reaction of self-destruction. Anyone who has spent time with Willie knows that he is as tightly wound as he is mellow. Bud Shrake, who helped Willie put together his autobiography, told me, “Willie has a violent temper. He gets so furious his eyes turn black, and he has to leave the room or kill somebody.” In the book Willie tells about a twenty-minute bloody brawl in a parking lot in Phoenix after a concert, some irate husband swinging a Crescent wrench and Willie defending himself with a two-by-four. “Having a temper is like being an alcoholic,” he says. “You always know it’s there.” He has learned to control his temper, or at least modify it. His mantra in the nineties is positive thinking. As he counsels in one his songs: “Remember the good times / They’re smaller in number, and easier to recall.”

Willie has battled his share of ailments—pneumonia four or five times; a collapsed lung that required surgery (he wrote the album Tougher Than Leather in the hospital), followed by a relapse when he ripped out the stitches while on a movie set in Finland; chronic back pain that dates from stacking hay bales as a boy; the usual prostate and bladder problems—but an uncanny survival instinct has enabled him to weather the ravages of time. “I’ve never been healthier,” he assures me. “I’m at the top of my game. I’ve got no domestic problems to speak of, nothing tearing me apart. I’m enjoying life more than ever: Now is the most important time, at least to me. If I start worrying about yesterday or tomorrow, I’ll get cancer and die.”

Watching from the theater wings at the Orleans Hotel, I realize again that Willie and his music are inseparable, that his songs are more than mere fingerprints of life, that they are a field of cosmic energy directing, shaping, and revealing everything he is or has been. Dressed in his stage “costume”—black T-shirt with sleeves and neck cut away, jeans, sneakers, a straw cowboy hat that he quickly exchanges for a headband—Willie is singing one of his legendary cheating songs, “Funny How Time Slips Away.” His tone is generous but accusatory, reflecting the mixed emotions that he was feeling when he wrote it in the late fifties. Though I can’t see her face from where I’m standing, I know that Willie is focusing on some knockout blonde with large breasts seated in the fourth row, singing directly to her. It’s a trick he uses to intensify his concentration onstage.

Willie was just 26 and in the middle of an incredibly hungry and productive period in his life when he wrote “Funny How Time Slips Away.” He wrote it and two other equally memorable classics—“Crazy” and “Night Life”—in the same week, driving in the early morning hours from the Esquire Club on the east side of Houston, where he was playing six nights a week, to the apartment in Pasadena where he lived with his first wife, Martha Jewel Mathews, and their three kids, Lana, Susie, and Billy.

These were his pre-Nashville days, and he was as poor as a Sudanese cat. Living in Houston, Fort Worth, San Diego, California, and a lot of other places, Willie worked by day selling vacuum cleaners or encyclopedias door-to-door and played by night in honky-tonks. He worked as a deejay where he could. Whatever it took to survive, Willie did. He sold all the rights to “Night Life” (including claim of authorship) for a measly $150. “Night Life” is one of the greatest blues numbers of all time and has been recorded by everyone from B. B. King to Aretha Franklin, but Willie gave it away for the equivalent of a month’s rent. He had to use the alias Hugh Nelson the first time he recorded it. He sold “Family Bible” for $50 and tried to sell “Mr. Record Man” for $10. Writers were like painters, Willie believed: An artist sells a creation as soon as it is finished so that he will have enough money to create again.

From his earliest years Willie knew that he was born to play music. Daddy and Mama Nelson, the grandparents who raised Bobbie and Willie after their parents divorced, taught singing and piano, filling their home in Abbott with music. Bobbie had the patience and the discipline to study music—her mastery of Beethoven, Mozart, and Bach is such that friends say she can play concert piano at any hall in the world—but with Willie it was all instinct. He started writing poetry when he was five and got his first guitar at age six, a Stella ordered by his grandparents from a Sears catalog. Within a few weeks he had learned the three chords necessary to play country music—D, A, and G—and begun compiling his own songbook, called Songs by Willie Nelson. Daddy Nelson’s death the following year had a profound effect on Willie. In his autobiography he wrote, “After Daddy Nelson died, I started writing cheating songs.” Heartbreak and betrayal animated all of his early writings.

Influenced by the voices and styles he heard on the radio—the songs of Bob Wills and Ernest Tubb and the voice of Frank Sinatra—Willie charted his destiny. Who could have predicted his amazing success or that he one day would be regarded by many, including me, as the greatest songwriter who ever lived?

“A lot of times when I’m driving alone,” Willie tells me, “and my mind is open and receptive, it will pick up radio waves from somewhere in the universe and a song will start. A line, a phrase. You don’t call up creativity; it’s just there. Like the Bible says, ‘Be still and know that I am.’ ”

“Do you pull over to the curb and make notes or what?”

“I never write it down until the whole thing is in my mind. If I forget a song, it wasn’t worth remembering.”

“But you must think about it.”

“I don’t like to think too much. It’s better coming off the top of your head. Leon Russell had this idea of going into the studio with no songs, just turn on the machine and start writing and singing. You remember winging ‘Main Squeeze Blues’?”

He’s referring to my wedding night in 1976. Phyllis and I had been married earlier that evening in the back room of the Texas Chili Parlor and eventually found ourselves at Soap Creek Saloon, where Willie was playing. On an impulse, I hopped onstage with Willie and began improvising a song that I called “Main Squeeze Blues.” I don’t remember any of it except the title, but the audience seemed to think it was pretty good.

“I see what you mean,” I admit. “When you’re sailing high or when you’re in a hard place worrying about the rent or food for the kids, something kicks in and words start gushing. But where do the melodies come from?”

Willie gives me the look you give a child who asks ridiculous questions. “I snatch them out of the air,” he says patiently. “The air is full of melodies.”

“A lot of times when I’m driving alone,” Willie says, “and my mind is open and receptive, it will pick up radio waves from somewhere in the universe and a song will start.”

Willie’s God-given ability to produce under pressure has delivered some of his best work. “Shotgun Willie,” which turned out to be the title song of his first successful album, was written in a couple of desperate minutes in the bathroom of a New York hotel room, on the back of a sanitary napkin wrapper. The night before he was due in the studio to record Yesterday’s Wine, he popped some pills and wrote the final seven tunes, including “Me and Paul,” celebrating his friendship with his longtime drummer Paul English.

Even in very personal moments, Willie can’t help working on his music. Some years ago, when he was trying to find the words for a father-daughter talk with Susie, Willie asked her to drive him from Austin to Evergreen, Colorado, and along the way he delivered his lecture by writing “It’s Not Supposed to Be That Way.” Willie says, “She was young, trying to grow up, and it occurred to me that it was easier to sing it than say it. She’s driving and I’m writing, singing, and picking, and finally it comes to me: ‘Hey, I’ve got another f—ing song half finished; all I need is a bridge and a steel turnaround!’ ” When the old well ran dry one time, Willie wrote a throwaway called, “I Can’t Write Any More,” immediately followed by a beautiful ballad, “Be My Valentine,” which celebrated the birth of his son Lukas, on Christmas Day, 1988.

The music stopped exactly two years later, when Willie’s eldest son, Billy, hanged himself. Of all the traumas in Willie’s life—the screwings by record and movie producers, an early career crisis so desperate that he lay down on a snow-covered street in Nashville and waited for a car to run him over, his famous battle with the Internal Revenue Service—the only one that really rocked him was Billy’s death. Willie has never talked about it or even acknowledged that it wasn’t accidental. He knows that I also lost a son, so when I ask him how he dealt with Billy’s tragedy, he thinks about the question for a long time, then says in a faraway voice, “You know, Gary, I just kept on. As it happened, we had a six-month gig in Branson, starting New Year’s Eve. I had a legitimate reason to cancel all my dates and go bury myself from reality, which is what I felt like doing. But that old survival instinct cut in. So I went to Branson, cussed the place, and threw myself into my work.”

As a young man, Willie made being broke and desperate into a profitable lifestyle, but he hasn’t written much in recent years. Now that he is rich and famous, he tells me, “I don’t have the leisure to write much anymore.” Maybe that’s true, I think. But it seems equally possible that at this stage of his life, Willie has said it all.

All of Willie’s marriages have been wild and tempestuous, but none quite as crazy as his marriage to Martha. Both of them loved the nightlife and its vicious cycle of drinking, cheating, fighting, and making up. Once, when Martha caught Willie fooling around, she tied him up with the children’s jump rope and beat the hell out of him. Another time she broke a whiskey bottle over his head. “Yeah, marriage to Martha was a running battle,” Willie confesses, recalling that in those days he always carried a gun—it was “part of my uniform.”

Willie’s second marriage, to singer Shirley Collie, was more placid, at least for a while. They were living in Nashville, though Music City wasn’t nearly ready for him. By universal agreement, a hillbilly song had just three chords; Willie’s songs had four or five. The formula for a country lyric involved one catchy line, followed by shallow sentiments of heartbreak and betrayal, rhymed predictably. Nothing in Willie’s songs was predictable. His style was deceptively simple, relaxed, and conversational: “Hello, walls. How’d things go for you today?” If the country music industry was threatened by such originality, country singers weren’t. Faron Young’s cut of “Hello Walls” sold more than two million records. Patsy Cline’s version of “Crazy” eventually won an award as the most played song on jukeboxes ever. Ray Price made “Night Life” his theme song. By the mid-sixties everyone was recording Willie’s songs, but no one was buying his records. Disillusioned, Willie bought a small farm outside Nashville and determined to be a gentleman farmer-songwriter. He smoked a pipe, wore overalls, raised weaner pigs with fellow musician Johnny Bush, and gained thirty pounds on Shirley’s good country cooking. By 1968, however, he was on the road again and life was becoming a living hell. “Shirley was boozing as bad as I was,” Willie says in his book, “and we were all swallowing enough pills to choke Johnny Cash . . .”

The marriage ended when Shirley opened a bill from the maternity ward of a Houston hospital—itemizing the cost of a baby daughter born to Willie Nelson and one Connie Koepke. A year before, the knockout blonde in the fourth row at a club in Cut ’n’ Shoot happened to be that same Connie Koepke. She became wife number three, even before his divorce from wife number two was finalized.

Willie’s marriage to Connie lasted seventeen years, far and away his personal best, but the strain of the road again took its toll. This time, actually, it was a road movie—Honeysuckle Rose—whose theme song, “On the Road Again,” Willie had written in flight on the back of an airline barf bag shortly after signing to do the movie. In the flick, Willie’s character, a musician, has an affair with Amy Irving’s character. At the same time, Willie had a highly publicized romance with the actress. Marriage to Connie flamed out during the filming. “Anything you want to tell me about Amy Irving?” I ask him on the bus. “She was something else,” Willie replies, then after a long pause, adds, “and I’d do it again.”

Willie met his current wife, Annie, on the set of the movie Stagecoach, where she was working as a makeup artist. “They say we marry what we need,” he says. “Kris [Kristofferson] married a lawyer, and I married a makeup girl.” They have been married for nearly ten years, a term that roughly corresponds to Willie’s average time with one wife.

“Marriage gets easier as you get older,” Willie admits. “There are still a lot of temptations out there. Mother Nature has a way of checking our appetites, but the girls still look good. If I stayed around [in a hotel or bar], the same thing would probably happen again.”

The advent of the Armadillo World Headquarters in 1972 was a revelation for all of us—especially Willie, who had just moved back to Texas from Nashville and was more or less retired from the national music scene. “We had been trying to travel all over the world with a seven-piece band and compete with the others,” he remembers, “but it just wasn’t working. I knew I could make a living playing honky-tonks in Texas.” Serendipity, in the form of a hippie hitchhiker, led Willie and the band to the soon-to-be-legendary Armadillo, a onetime National Guard armory that entrepreneur Eddie Wilson had transformed into a dance hall. This was the start of a wonderfully weird convergence of hippies and rednecks that would change music history.

I first met Willie on August 12, 1972, a few hours before his first gig at the Armadillo. Both of us were in our late thirties and relatively new to psychedelics and long hair. A couple of friends and I were in the small office that the Armadillo had set aside for Mad Dog, Inc., a shadowy organization that Bud Shrake and I had founded at roughly that same time. Artist Jim Franklin was decorating a wall of the Mad Dog office with a portrait of a crazed Abe Lincoln when we spotted Willie and the band across the hall. I didn’t recognize him at first. I had been a fan since 1966, when Don Meredith handed me a copy of Willie’s album that was recorded live at Panther Hall: Listening to it over and over that night was one of the most profound experiences of my life. The album cover pictured a straight-looking country singer with short hair and a bad suit. He clutched a guitar, but from his looks it could have easily been a pipe wrench.

Willie was different now. His hair fell almost to his shoulders, and though he was still clean-shaven and passably middle class, he was obviously undergoing a metamorphosis. “I saw a lot of people with long hair that day,” Willie recalls. “People in jeans, T-shirts, sneakers, basically what I grew up wearing. I remember thinking: ‘F— coats and ties! Let’s get comfortable!’ ” The real eye-opener for me came that night. Who in his right mind could have predicted that the same audience that got turned on by B. B. King and Jerry Garcia would also go nuts for Willie Nelson? This Abbott cotton picker had merged blues, rock, and country into something altogether original and evocative.

Success came rapidly after that. His Shotgun Willie album sold more copies in Austin than most of his other albums had sold nationwide. The next album, Phases and Stages, sold even better. Willie decided to hold an annual picnic in the style of Woodstock. He appeared onstage at the first one, in 1973, in cutoffs, sandals, long hair, and a beard. Two years later he had a huge hit with “Blue Eyes Crying in the Rain.” By 1978 his image and reputation were so established he convinced executives at CBS Records that his next album ought to be a collection of standards like “Stardust” and “Moonlight in Vermont.” At first they thought he was crazy, but Willie pointed out that “my audience now is young, college age, and mid-twenties. They’ll think these are new songs.” He was right. Stardust was a pivotal album for country music, opening up a whole new audience. “Willie has always been a prophet, slightly on the edge,” Rick Blackburn, the president of CBS Records Nashville, said later.

The early seventies were also the formative years for Willie’s other “family”—a motley and colorful crew of itinerant musicians, promoters, and roustabouts that Willie has collected along the way. Billy “B. C.” Cooper chauffeured Willie around in a six-cylinder Mercedes before the first bus was purchased and doubled as his bodyguard; he’s one of the last of the original family. “I was just a old used-car salesman,” B. C. told me recently at Willie World, where he now resides in peaceful retirement, “but Willie took a liking to me and told me to follow him, and I been following him ever since.” Larry Gorham was a Hell’s Angel in San Jose before Willie appointed him chief of security. Paul English was a Fort Worth pimp and burglar when Willie asked him to play drums in 1966. Mickey Raphael was a teenage nobody when he cornered Willie outside a Dallas recording studio and applied for a job as the band’s harmonica player. “Follow us, kid,” Willie instructed. Willie’s judgment for new talent is instinctively good, and once discovered, they stay for life.

Backstage at the Orleans, I meet another of Willie’s longtime mates, Phil Grimes, now a Las Vegas developer and real estate executive. In the early seventies he was a freelance reporter for the Associated Press in Austin. “I went out to do a story on Willie,” Phil tells me. “I got on the bus and it was three and a half weeks before I could find my way off.” Looking around, it occurs to me that Willie probably has the last group of geriatric roadies in the business.

Saturday night in Las Vegas, Willie gives the Orleans Hotel audience two and a half hours to remember. He goes from cheating songs and blues to gospel numbers like “Amazing Grace” to a Sinatra-like cover of “Stardust” to a deeply moving rendition of his current philosophical favorite, “Still Is Still Moving to Me.” By the end of the show fans have gone berserk, clapping, rocking, dancing in the aisles, calling his name. “We love you, Willie!” a female voice cries out. Willie has already tossed two headbands to his fans, and now he peels off his sweat-soaked black T-shirt and lobs it to a woman in the fourth row. The Orleans higher-ups are stunned by the reception. They had no idea how Willie would be received—they usually book acts like Phyllis Diller and Eddie Arnold—and immediately sign him for three dates in 1998, including another long Thanksgiving weekend. “It’s not the three straight sellouts that impressed them,” says Scooter Franks, Willie’s traveling concessions manager. “What they care about is the drop—the money that people gamble after the show. We told ’em, ‘Willie is like Sinatra: his people drink a lot of whiskey and they stay to gamble.’ ” Long after his roadies have cleared the stage and loaded the buses for the trip home to Austin, Willie is still signing autographs down front.

There is such a powerful presence about Willie that people sometimes believe he’s a mystic or even a messenger from God, a misinterpretation that he hasn’t always tried to correct. Billy Cooper almost convinced me that Willie has a magical ability to commune with snakes and birds and that he can, with a wave of the hand, convert negative energy to positive. Stage manager Poodie Locke tells of a ferocious gun battle in a parking garage in Birmingham, Alabama, after a concert, with cops squatting in doorjambs and civilians diving for cover. In the teeth of the chaos Willie calmly stepped down from the bus, wearing tennis shoes and cutoffs with two Colt .45 revolvers stuck in the waist, and inquired coolly: “Is there a problem?” In an instant, all guns were holstered and Willie was signing autographs. “He’s got the kind of aura to him that just cools everything out,” Poodie explains.

“There is such a powerful presence about Willie that people sometimes believe he’s a mystic or even a messenger from God, a misinterpretation that he hasn’t always tried to correct.”

Willie believes that his life is a series of circles in which he is continually reincarnated, each version a little better than its predecessor. There is some theological support for this belief. Kimo Alo, one of the magician-priests, or Kahunas, who live on the island of Maui, where Willie has a vacation home, believes that Willie is “an Old King,” reincarnated to draw the native races together. When I ask Willie about the Old King theory, he dismisses it—though I suspect he secretly thinks it’s reasonable. In his autobiography he wrote, “Even as a child, I believed I was born for a purpose. I had never heard the words reincarnation or Karma, but I already believed them and I believed in the spirit world.”

Raised as a staunch Methodist, Willie was taught that if he drank or smoked or went dancing, he was doomed to hellfire. He never bought this doctrine: Willie’s God was always willing to give a guy another chance. An incident in the fifties, when he was teaching Sunday school at the Metropolitan Baptist Church in Fort Worth, reinforced this conviction. His preacher gave him an ultimatum—stop playing in beer joints or stop teaching Sunday school—and Willie quit the church for good, disillusioned with a policy that summarily condemned people like him. He went to the Fort Worth library and started reading books on religion. “Soon as I read about reincarnation,” Willie wrote, “it struck me just the same as if God had sent me a lightning bolt—this was the truth, and I realized I had always known it.” Willie had the good sense to see that it would take many more reincarnations for him to triumph over his lustful urges, but at least he knew he was on the right track. Today, Willie and family worship at the one-room church on Willie World’s western film set, where Red Headed Stranger and a bunch of other movies were shot. Though the church is empty except for some benches and a portrait of Jesus hung by Lana and Bobbie, the music on a Sunday morning will stir the jaded soul.

Willie often jokes that he is “imperfect man,” sent here as an example of how not to live your life. This was the theme of Yesterday’s Wine, his most personal and spiritual album, and arguably his best. Written in the early seventies after a series of personal disasters, including a fire that burned his home in Nashville (Willie managed to save his marijuana stash from the ruins), the album follows a man from birth to death, ending with him watching his own funeral. “Maybe I was imperfect man, writing my own obituary,” Willie tells me during our conversation on the bus, breaking suddenly into song: “There’ll be a mixture of teardrops and flowers / Crying and talking for hours / And how wild that I was / And if I’d listened to them I wouldn’t be there.” The album also includes a passage in which God explains to imperfect man that there is no explanation for the apparent random cruelty of life: “After all, you’re just a man / And it’s not for you to understand.”

Two weeks before Christmas I drop by Bobbie Nelson’s home on the sixth fairway at Pedernales Country Club in Willie World and am surprised to find Willie sitting at the kitchen counter, rolling numbers and listening to a blues album he was recording recently with Riley Osbourn and some other blues players. Bobbie is cooking breakfast—sausage, eggs, biscuits, and gravy. This was supposed to be a one-on-one interview with her, but it turns out to be something else. We sit for a while, sharing a smoke and listening to some great blues.

Pouring us more coffee, Bobbie asks Willie in her soft, sweet voice, “Remember where we first heard the blues?”

“Out in the cotton fields in Abbott,” Willie says. “Somebody would start singing ‘Swing low, sweet chariot’ and somebody else would pick it up.”

Bobbie has faintly romantic memories of the cotton fields, but not Willie. “By the time I was seven or eight,” he says, “I was working the rows for a couple of dollars a day. My desire to escape manual labor started back there in the cotton fields.”

A seven-foot grand and a smaller piano dominate the living room, and I remember reading that Bobbie’s first piano was a toy that she and Willie made out of a pasteboard box. The keyboard was drawn in crayons, and Bobbie sat under a peach tree in the back yard, practicing for hours. For years on long bus trips across the country, she propped a cardboard keyboard in her lap, shut out the world, and followed with her fingers as the works of Mozart or Bach played inside her head.

After a while, Lana stops by. She has brought Willie’s Christmas present. He’s leaving the following day for a couple of months in Maui with Annie and his boys. We all sit around the dining room table, passing heaping platters of biscuits. Bobbie and Lana are the two people closest and dearest to Willie, and they fuss over him like mama hens, tending to his slightest wish. Watching him in the nest of his true family, I realize that the private Willie is not much different from that little boy who grew up in Abbott. He knew that he was special, and so did everyone else.

“I married Bud Fletcher when I was sixteen,” Bobbie says as she refills the gravy bowl. “Bud formed a band called the Texans, with me on piano and Willie on guitar and vocals. Willie was making eight dollars a night, which was very good money for a thirteen-year-old.”

“The forty to fifty dollars a week we took home to Mama Nelson was a fortune back then,” Willie says. “I’d hock my guitar every Monday for twenty dollars, and Bud would get it back out of hock on Friday so the Texans could hit another lick.”

“Of course, Mama didn’t like us playing beer joints.”

Willie laughs, remembering. “She didn’t even want me going on the road. Shadowland was five miles away—in West. But that was the road to her.”

If Willie has learned anything in these 65 years, it’s that Mama Nelson was right. When your life’s the nightlife, all roads are pretty much the same.

- More About:

- Music

- Marijuana

- Longreads

- Willie Nelson

- Bud Shrake

- Bill Wittliff

- Austin