“The true balance of life and art, the saving of the human mind as well as the theatre, lies in what has long been known as tragicomedy, for humor and pathos, tears and laughter are, in the highest expression of human character and achievement, inseparable.”

So wrote the great New Yorker humorist James Thurber, whose own brand of comedy, superficially whimsical, roiled just under the surface with dark and treacherous psychological undercurrents.

The same could be said, though in reverse, of Carol Burnett’s “The Family” sketches, those ten-minute vignettes of thwarted dreams, familial aggression (always passive at first, before all Southern graces invariably fall by the wayside) and ancient, unresolvable grudges set in the lower middle class, bourbon-breathed San Antonio of Burnett’s Depression Era childhood.

Burnett has said that Eunice Higgins, the aggrieved daughter of perpetually glum, martyr-complex mother Thelma Harper (Vicki Lawrence) and wife of dullard hardware store owner Ed (Harvey Korman), was her favorite character from the entire run of her 1970s variety show.

Which is as it should be, as those sketches stand the test of time as painfully hilarious exceptions to the often-corny rule of seventies TV, a rare enough feat on its own. But they are even better than that. To my mind, “The Family” sketches are legitimate works of art: Tennessee Williams, not quite parodied, but mercifully lavished with the pressure-valve release of laughter; darker, though equally poignant Shelby Foote playlets, again, slathered with a ladle full of laughs mostly absent from Foote’s work; or even a (slightly) less tragic and far more humorous Madame Bovary set in South Texas.

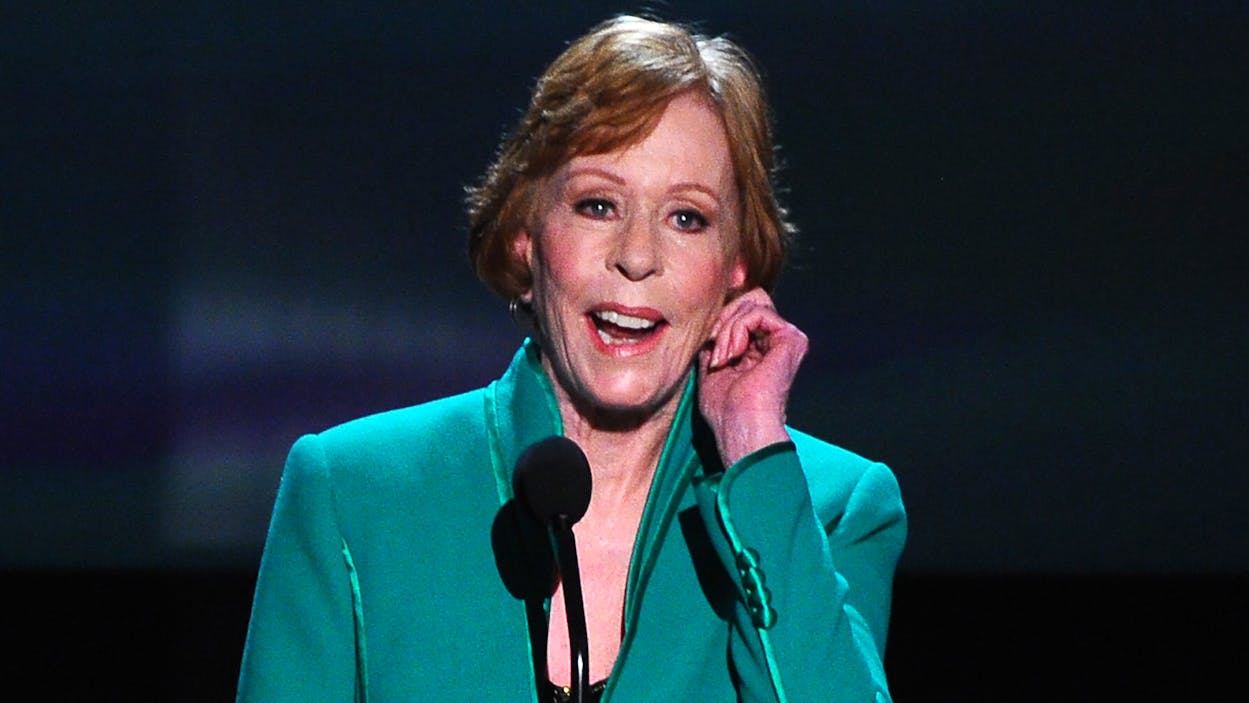

As the crowning achievement of her glory days as a dominant force on 1970s TV, Burnett’s portrayal of Eunice played no small part in Saturday’s Screen Actors Guild Lifetime Achievement Award, one presented to her by reigning queens of comedy Tina Fey and Amy Poehler, and one Burnett accepted while wearing a pair of fluffy house shoes.

Space doesn’t allow here for a full appreciation of Burnett’s work as a singer, dancer, actor, and comedian, even if you look solely at her work on the eleven seasons of her eponymous variety show. It’s best to confine it to her favorite recurring sketch and her favorite character: Eunice Higgins and “The Family,” and to further restrict that to one of the sketch’s finest installments.

Sorry! has it all. A nasty little game like this Parker Brothers special seems to have been calculated to bring out the worst in its players, but it certainly brought out the best in Lawrence, Korman, and especially Burnett.

Here we see Eunice’s misplaced, inevitably-crushed optimism (“I think mama is mellowing these days!”); her gushy nostalgia for good times that never existed and her unshared zest for life (“You remember how we used to sit for hours and play Sorry?”); her mercurial shifts between glee, rage, and tears; the daggers she shoots with her eyes towards mama’s many acts of barely passive aggression, the little touch to her hair after she finally boils over in a disagreement (“IT WAS A SEV-ENNNNNN!”) over who rolled what on the dice.

Perhaps only Julia Louis-Dreyfus is Burnett’s equal as a master of facial expression and body language. Watch Burnett’s suppressed eye-rolls, her flaring nostrils, her tight, whitened lips, her folded arms: in an age of hams, Burnett never overacted. Her performances remained just on the right side of mugging, even when her character was raging. Around the 13-minute mark we see her ability to hold it together under the extreme duress of Vicki Lawrence’s fearsome improv skills: watch Burnett struggle to retain composure after Lawrence strays from the script with lines like: “I think somebody blew your pilot light out.” After collecting herself for a few beats and stifling a giggle by exhaling “Ohhhh boy!” as Lawrence looks on in full, glowering, hands-on-hips bulldog mode, Burnett manages a spot-on riposte.

But then nothing, not even Burnett, could withstand Lawrence’s response: watch the wave of emotions that passes over her face as Lawrence hollers, “You’ve got splinters in the windmills of your mind,” and “You’re playin’ hockey with a warped puck.” And finally, after all that, we see another abrupt shift in Burnett’s key: after ten minutes of barely contained rage and airing of generations-old resentments, capped by a mighty struggle to hold it together under Lawrence’s impromptu shenanigans, a lucky roll of the dice transforms Eunice into a pralines-moonlight-and-magnolias Southern belle again, and life, and the game of Sorry!, goes on.

Mostly unseen (though not always), though apparent to those who can read between the lines, the sketches are shot through with themes of alcoholism drawn from Burnett’s childhood. Only functional drunkards are as mercurial as these characters, apt as they are to go from maudlin to enraged, sugar-sweet to snake venom-mean, at the tumble of a pair of dice.

Burnett did not write these sketches, but they were brought to life through her shared experiences with staff writers Dick Clair and Jenny McMahon, both also survivors of challenging upbringings. In Clair and McMahon’s original draft, Burnett was to play the mother, and the sketches were to be set in the generic Midwest. On reading the scripts, memories of her childhood on West Commerce Street in San Antonio kept boiling to the surface: she related far more to Eunice than Thelma or Ed, and she conceived of Clair and McMahon’s memories as variations of her own upbringing as a child of alcoholics: Texans who dreamed of Hollywood stardom. She would play Eunice, and though she was 16 years younger, Lawrence would play her mother. As Lawrence reminisced last year:

[Clair and McMahon] both came from dysfunctional families, [and] they wrote this beautiful homage to their crazy families and intended for Carol to be Mama. When she saw the final draft of the sketch, she said, “I want to be Eunice” — very upsetting to the writers. Then she said, “I think Vicki would be great as Mama” — doubly upsetting to the writers. Then we got to the rehearsal hall and she said, “You guys, I think we need to do it Southern.” Well, the first time the writers saw us do it, they got up and walked out. … They said, “You’ve ruined it.”

Neither McMahon nor Clair were from the South, yet they both believed that setting giving these characters twangs would alienate Dixie audiences. Burnett won out, and the skits went on as she envisioned them. Nowhere were they more popular than below the Mason-Dixon line, which then as ever, was a region starved for warts-and-all portrayals. (As a Texas/ Southern kid, the only non-cartoonish network TV alternative I had was reruns of Mayberry RFD; clever, but idealized, and far removed from the dysfunction of my own childhood.)

“Oh, I loved Carol Burnett,” a rural Texas cousin told me. “This town is a lot more like Peyton Place than Mayberry. We have so many secretisms. That’s one reason I moved out of town and out to the country.”

Who among us— Texan kids in the city a generation or two removed from small towns or the country—couldn’t relate? Burnett, Lawrence, and Korman’s drama lived right on the edge of my own memory, in the stories my ancestors chuckled over ruefully. On my mother’s side of the family, three of my four great-grandparents were heavy drinkers. There was my great-grandfather, the sea captain/ship’s pilot from Beaumont. “He was so drunk at one dinner I threw a glass of ice water in his face,” my grandmother told me only this week. She was a teenager at the time. “The family was mortified, but I just had to do it.” On the other side, there was my grandfather’s mother, a cowgirl from Granbury, who once abruptly took extended leave from a family gathering to the point where a search party had to be organized. She was found, eventually, sulking under the bed, nursing her grievances and a bottle of sour mash. Such scenes seem now to me like outtakes from “The Family.”

And then there was the set design and the wardrobe, so close to the reality of Texas even 35 years ago. Around 1980, when I was 10, my uncle Joseph Lomax took me to visit his mother’s few surviving relatives in Clarksville, a once-proud, now-withering county seat a few miles south of the Red River, not far from Paris. I slept on the couch at a house near the courthouse square, and I felt like I had stepped on to the set of “The Family.”

There were the 1930s appliances and the Victorian house with the wraparound porch. Here was the bouquet of floral prints, as both wallpaper and on the dresses adorning the buxom matrons, most of whom also sported blue-rinsed hair, some of it full-on grape soda colored. I still remember Uncle Joseph’s cackle when I asked him in all seriousness why my aunties and cousins had purple hair. It was confusing to find what I thought a punk influence among such fancy ladies who lived so close to Oklahoma and so far from London.

After that trip, I really got Burnett’s “The Family.” I’d been to the time and place that produced Burnett’s sketches, though I believe that you really don’t need such a study aid to appreciate them today. If you can laugh, or cry, or both at the same time, you will still enjoy these sketches.

And that’s why I think they stand as lasting works of art even now. Paraphrasing Steve Earle, Carol Burnett is the funniest Texan who ever lived, and I’ll stand on Bill Hicks’s, Mike Judge’s, or Ron White’s coffee table in my cowboy boots and tell him so.

Or as Tina Fey put it the other night, “The point is, Carol is better than all of us. We’re going to give her a prize for it.”