The most unlikely star at the 2015 Sundance Film Festival? Former Eagle Pass mayor Chad Foster, who was best-known for his opposition to the federal border fence. Flawlessly bilingual and beloved in both Eagle Pass and Piedras Negras, Foster lies at the center of Bill and Turner Ross’s Western, a movie that’s less about immigration politics as it is a dying way of life: one centered around the cultural ideal and economic artery of shared borders. The documentary, which won a “Special Jury Award for Verite Filmmaking” at Sundance, now screens at the SXSW Film Festival in Austin, as well as New Directors/New Films in New York next week.

“Have you tried to talk Chad Foster into running for president?,” an audience member at Sundance asked, not knowing that Foster died of cancer at the age of 63, in July, 2012. This detail is absent from the film due to the Ross brothers’ naturalistic style. Aside from a brief identification of Foster and the film’s other main character, cattle broker/importer Martín Wall, Western shows and almost never tells, layering impressions and emotion more than information. Like the brothers’ previous two films, 45365 (about their hometown of Sidney, Ohio) and Tchopuitoulas (about New Orleans), it’s a portrait of an America that’s little-seen, from the corrido-singing cowboys on Wall’s ranch to Foster’s church attendance.

“We want to give a handshake to a situation that’s usually a headbutt,” says Turner Ross. When the brothers first arrived in Eagle Pass, the cartel activity in Ciudad Acuña hadn’t touched Piedras Negras, but soon enough, the violence hits. Foster and Wall’s conviction that there’s no reason to panic is not easily shaken—“Oh, you drank this coffee too?” Foster says to a Spanish-speaking, Mexican-American cattleman who is now scared to go to Mexico—but when USDA veterinarians are banned from crossing over, Wall is temporarily left without a business (and can’t help invoking Lonesome Dove as he surveys his empty pens).

SXSW is a familiar spot for the Ross brothers: 45365 won the Grand Jury Prize for Best Documentary Feature at the 2009 festival, and Tchopuitoulas premiered there in 2012. Western was their first film to be showed at Sundance. “SXSW launched us,” says Turner. “It’s still a little odd how they picked our little movie out of a very big pile, but once upon a time they did. Returning to SXSW with a Texas movie is a very positive thing.”

Jason Cohen: What was the movie you thought you wanted to make, before you actually got to Eagle Pass?

Turner Ross: The generic idea was to see what the modern frontier looks like. To base our thematic ideas on what a nonfiction Western would be: the archetypes and landscapes we’ve come to know, or think we know. To immerse ourselves in it and see what the reality is.

JC: Did you travel all along the border, or to other states?

Turner: We did. We thought we knew what kind of visual landscape we wanted. That ended up being either the New Mexico border or the Texas Rio Grande border. When we arrived in Eagle Pass and you see these intertwined communities facing each other, literally going back and forth over the bridge, the setting is there, the context is there. As I started to dig a little bit deeper, I realized the backstory of the place—the stories of Chad Foster fighting against the border wall. He invited us to come down and see what it was. We stayed for thirteen months.

JC: Has it ever happened to you quite like that before, where you felt like you hit the jackpot with a character?

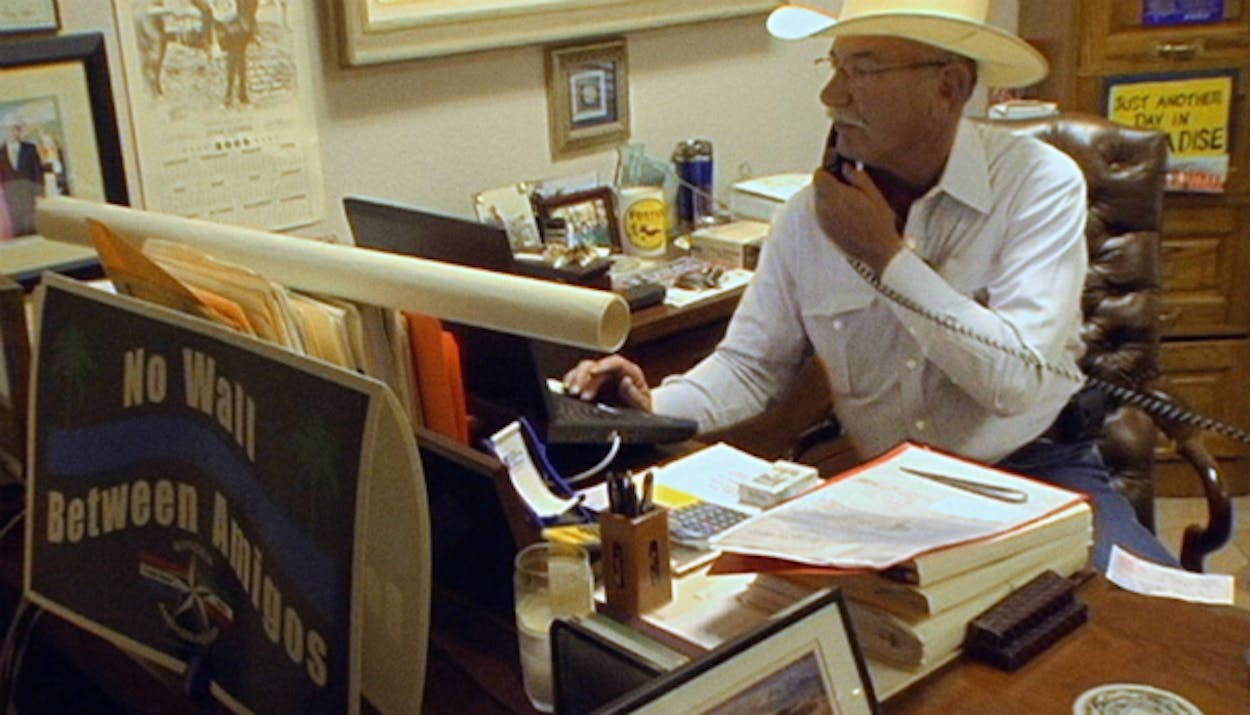

Bill Ross: I think that’s happened to varying degrees on each of the films. Certainly, when you walk into Chad’s office, and he looks the way he does, and talks the way he does, yeah, lightbulbs go off in your head. You’re immediately feeling like you’re in Tommy Lee Jones’s office.

JC: At Sundance you also said, “We found John Wayne.” He and Martín Wall couldn’t have fit into your themes more naturally, compared to what you might find in a more politically oriented “border movie.

Turner: The things that we wanted were there, so we knew to look for them. We weren’t going to make a “border film”; we were going with an entirely different impetus. Creative and thematic ideas, rather than journalistic or sociological ones. We’re not going out to save the day, we’re going out to capture the times and place that we’re a part of.

JC: Once you meet people, how long do you wait before you actually start shooting?

Turner: There’s no waiting. A lot of times we go into the situation filming, and that breaks down that wall pretty quickly.

Bill: We filmed our first conversation with Chad.

Turner: We introduce ourselves, we say, here’s who we are, here is what we do, and here is why we’re here doing that. And then we start doing it. If someone’s not amenable to it, you get that out of the way right away. And maybe it does take time to get to that place where it’s just happening naturally, and you seem not to exist in that space. But we build that while we’re filming.

JC: The film eschews exposition; only Chad, Martín, and Martín’s daughter Brylyn are even formally identified. Were you never tempted to throw in a little bit of narration or explanatory text?

Bill: When we think about these films, we just want them to be, existing. When you dream, you don’t have subtitles, and you don’t have cards that tell you which direction you want to go. It’s just imagery, and sometimes it doesn’t make sense, and then a little bit later on it might. I would much rather be allowed to look around myself and try to find meaning on my own. I think it’s a much more rewarding experience.

JC: Did you consider a postscript about Chad’s death?

Bill: We always treat it as, we can only talk with regards to the time that we were there.

Turner: If there’s more to your story, then why is your story ending? We weren’t there while the stories were going on before, and at a certain point we leave.

JC: That approach won you a “Special Jury Award for Verite Filmmaking” at Sundance. What does that word mean to you?

Turner: You want to know the best thing that happened at Sundance? The award was awesome and the recognition is so amazing, but soulfully, spiritually, professionally, the best thing that happened was, [the late documentary filmmaker] Les Blank’s wife and collaborator [Chris Simon], came to the premiere, and a few days later we got an email from her telling us how much she liked the film. And at the very end of it she said, “I think he really would have enjoyed this. Thank you for keeping the spirit of verite alive.” So if that’s what that means, then we are thrilled to be associated with that.

Bill: It’s not a word we use daily.

JC: There’s always something epistemological about the term. It’s still the “truth” through your camera, and your presence in a place.

Turner: There will never be an answer to that debate. It’s always gonna be a personal truth.

(Turner and Bill Ross. Photo by Jess Pinkham)

JC: I got the impression a few people at Sundance walked out because they couldn’t deal with some of the graphic realities of ranching and the rodeo. You guys are from Ohio. Was that aspect of rural life new to you as well?

Turner: That was a new deal, yeah.

Bill: When we first showed up on Martín’s ranch, he didn’t quite know what to make of us. He actually took Turner out shopping, so he’d look more appropriate.

Turner: He did not like what I had going on. We went and got some proper jeans, pearl-button shirts, and boots. And a nice hat for the warm weather. I was better embraced after that.

Bill: For some reason I got a pass on that whole deal.

JC: The film is full of characters you might have developed further if you wanted to, but one of them particularly stands out: the floppy-hatted, informal border sentry who spends his time watching and patrolling the Rio Grande.

Turner: He has a great story all his own, but for us, in terms of the filmic language of what we’re doing, he seemed to speak for something a lot more if he didn’t necessarily speak. He’s the watcher. It’s very much a facet of who he is and what he is. He’s also very, very, very unique. Dob Cunningham is his name. Former old school border patrol agent who just—he never quit. We weren’t the first ones to get to him.

(In fact, Cunningham, below, was the subject of Pamela Colloff’s April, 2001 Texas Monthly article, “The Battle for the Border.”).

JC: I know the movie speaks for itself and you tried to come in without preconceptions, but how did you feel about the place after thirteen months there.

Turner: Well, in two ways—in a mythological aesthetic movie way, and in a very personal humanistic political way—it’s not black hat/white hat. It is a very liminal, grey, cultural area, which is just so rich, and it’s so strange to see it divided in such a way. It’s no longer a simply local, neighborly thing, it’s something bigger than those towns, bigger than the individuals. You take these huge political issues and you don’t see the way of life, the cultural space, the families and business, this very complicated historical relationship. There is no good guy or bad guy, just a whole lot of people dealing with circumstance, hoping that what they think of as their way of life continues. It gave us a real eye into that.

Bill: My takeaway is about the same. It just gave me an understanding of how it was down there, and not what we read and hear every day. One of Chad’s favorite things to say was, “the only thing a wall was going to do was make somebody in Missouri sleep better at night.” It was really beautiful to see the harmony of that culture, and to see it pulled apart while we were there was difficult.

JC: It also must have been bittersweet, to see Chad get such a reaction at Sundance and not be there.

Turner: It wasn’t lost on him that he had some star appeal. He wanted to be a movie star just like everybody else. I spoke to him right before he died, and I think he had a pretty good idea of what we were doing. I hope he would have been proud. One thing I know for sure, if he was around, we wouldn’t get a lot of talking done.

Bill: I kept envisioning him walking down the street [at Sundance]. He would have blown everyone away.

Turner: Yeah. A real mustachioed, smoking, talking, tall-ass cowboy in a ten-gallon hat. He was the real deal.