Bernie Sanders has never been a member of the Green Party, but you wouldn’t know it from listening to the folks at its convention this weekend in Houston. The party to the Democrats’ left met on the second floor of the University of Houston’s student center to nominate Massachusetts activist and doctor Jill Stein as its presidential candidate—but Sanders came up a lot in the process.

As political conventions go, it wasn’t exactly the DNC or the RNC. The set-up was nice: lots of tall windows, comfortable chairs, just a staircase away from a Panda Express-McDonald’s-Chick-Fil-A combo, but it wasn’t a basketball arena. Expecting that it should be, though—or at least expecting that legitimacy in American politics is determined by the ability to rent a basketball arena for your nominating convention—is one of the things that makes Greens bristle.

The Green Party hasn’t been relevant in American politics in a long time, but the party believes that Sanders—who, again, isn’t a member of the party, has endorsed Hillary Clinton, and has urged his supporters not to vote for the Greens—might change the math on that. Sanders’s campaign was the furthest left a major American candidate for president has run in at least a generation, and crowds responded to it in a markedly different way than they did, say, to the tepidly progressive campaigns of Dennis Kucinich in the mid-aughts. His race against Clinton shook the Democratic Party to its core, and resulted in a platform packed with Sanders’s goals—but it also left thousands and thousands of his most ardent supporters heartbroken as they watched him endorse his opponent at the Democratic National Convention.

Many of those supporters will dust themselves off, follow his lead, and vote for Clinton in November, but not all of them. And that makes the Green Party interesting to watch for the first time in more than a decade.

Back in 2000, of course, the Greens mattered quite a bit. They had nominated Ralph Nader, and his campaign—which came into existence as many Americans felt that the differences between a two-term vice president and the son of the sitting president’s successor were negligible—struck a chord with more Americans than a third-party candidate had in modern times. The Greens pulled 2.8 million votes that year, Al Gore won the popular vote, George W. Bush won the electoral college. Democrats blamed Nader, 9/11 happened, we invaded Iraq, and roughly 2.7 million of those people who voted Green in 2000 decided that maybe it wouldn’t be such a great idea to do that again in 2004 and 2008. A relative comeback year for the party in 2012 saw them nominate Stein for the first time, and she tripled the party’s success from 2008’s numbers—but still secured fewer than half a million votes.

So here was the big question at the Green Party Convention in 2016: does this party matter? Jill Stein won’t win the presidency, but nobody in Houston this weekend believed that she would. (When Wikileaks founder Julian Assange addressed the convention remotely from London, he had to add a “No, I’m serious,” after he said that Jill Stein might become president, citing Brexit as proof that the unexpected can happen.) Outsiders are extremely hot in 2016, though, and many of Stein’s supporters are folks who have a Bernie Sanders t-shirt or five in their dresser. The line in 2000 was that there wasn’t enough difference between Bush or Gore to warrant voting for either of them. You didn’t hear that echoed about Clinton and Trump—the unique nature of the Republican candidate would make that line hard for even the most passionate Greens (or Sanders supporters) to swallow. But for the Greens, the fact that two candidates with low approval ratings, but decades-long careers in the public eye are the major party options is an injustice.

The argument for why the Greens exist is also the rationale the party’s supporters use for why it’s going to have a big year. “We have an election year crisis that’s unfolding in several different ways,” says Scott McLarty, the party’s media director. “The Republican party has been essentially taken over by its most extreme and hysterical factions. We have a candidate this year who might be the worst in historical memory. Then we have a candidate who considers herself above the law,” he said, referring to the fact that the FBI declined to indict Clinton over her use of a private email server.

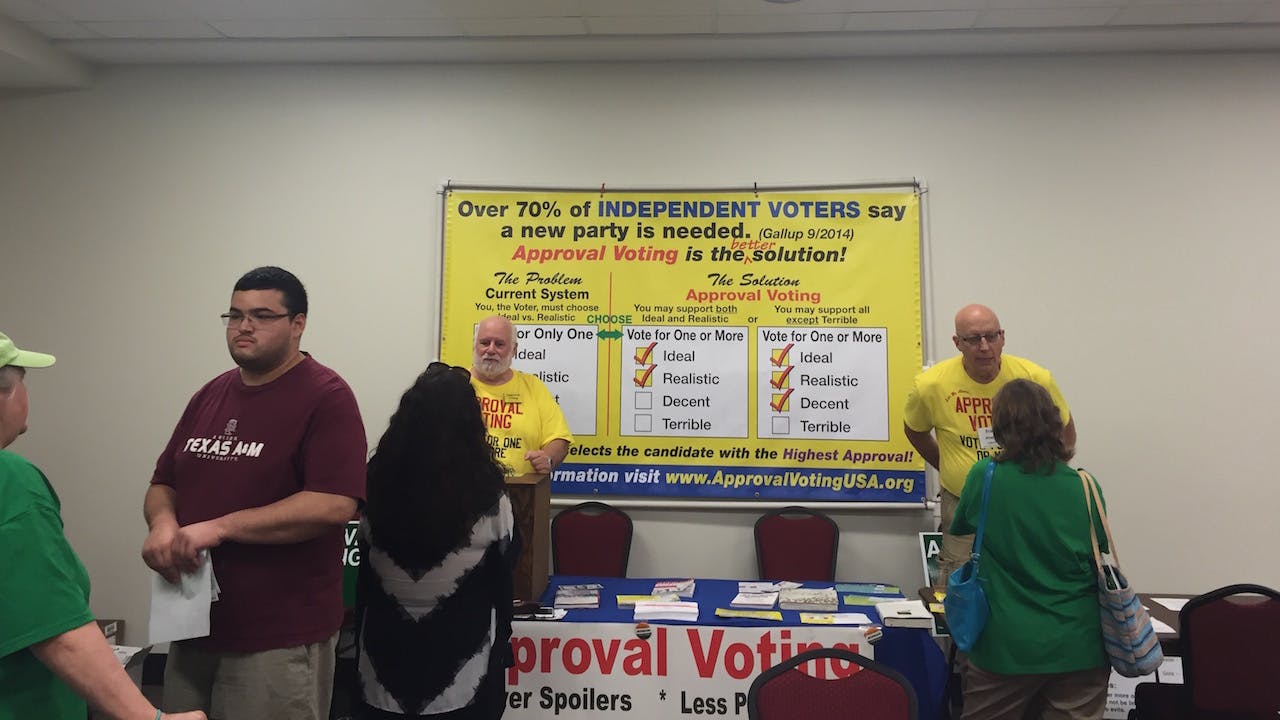

“We need more options” is a popular sentiment. Americans like having a lot of choices, anyway—there are currently 28 varieties of Mountain Dew distributed in the U.S.—and McLarty’s argument resonates with those looking for more. People at the convention were arguing not just that we should have more choices, but looking at how that might actually work. For example, there were conversations about “approval voting,” where voters would check off all acceptable candidates on a ballot, and whoever received the most approval votes would win. That’s just one of the ways that the Greens see that alternative parties could exist in a country that’s very rarely elected anyone who isn’t a Democrat or a Republican (or their predecessor parties) to high office.

And they have their eyes on positions outside of the Oval Office too. Presidential campaigns get the national headlines, but one way that the Greens matter in 2016 is that they give a training ground to candidates for local and state races. Most of them—maybe all of them—are going to lose those races. (The Greens have won a handful of seats in a handful of statehouses—in Maine, Arkansas, and California—and on city councils in small towns and cities, plus a few years in the mayor’s office in Richmond, California, but the list of electoral victories is short.) And though McLarty’s dreams of success are tempered—”If Jill were to get more than 5 percent on election day, that would qualify the 2020 Green Party nominee for very generous matching funds from the Federal Elections Commission”—the candidates running as Greens around the country have even more open-ended ideas about what that means to them.

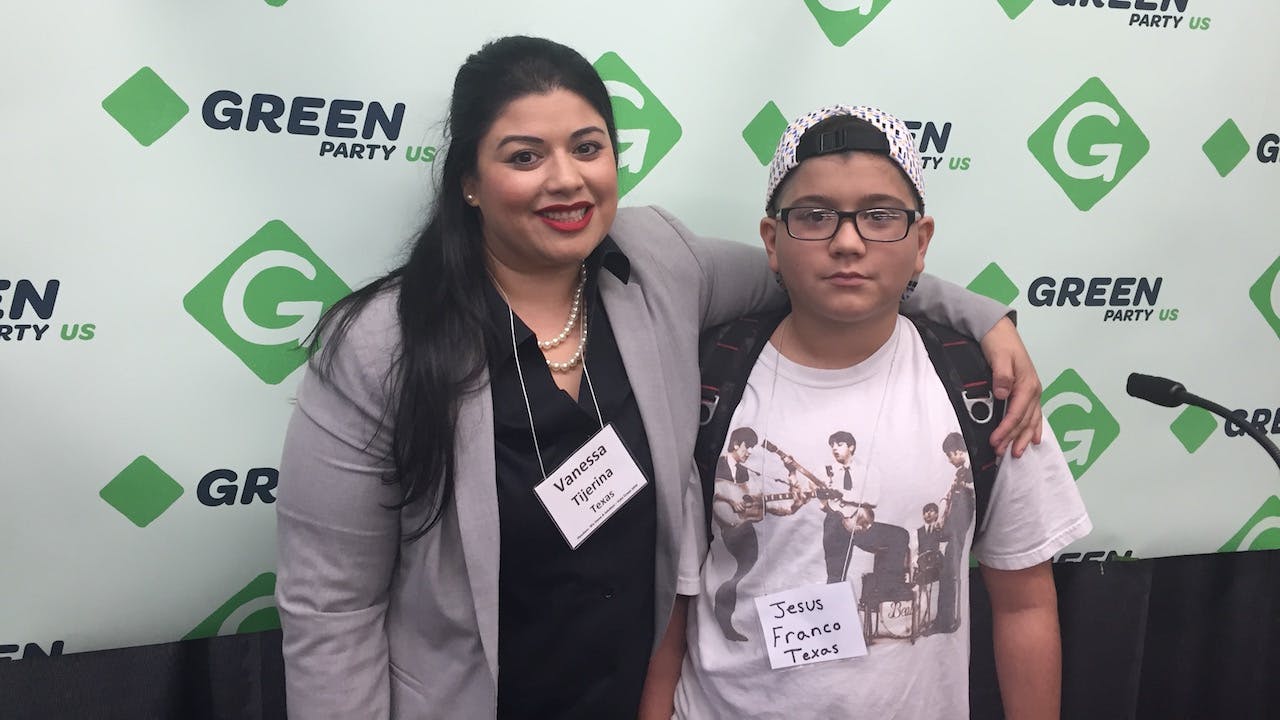

Vanessa Tijerina, the Green Party nominee for the U.S. House of Representatives in Texas’s 15th congressional district, is one of them. “It’s not just about winning. If we can go in there and change the political climate, that’s what we need. The spectrum has changed to the right to the point that it’s normalized down there that a centrist Democrat is a liberal, and that’s not the case,” Tijerina says. She’s running for a seat that’s being vacated by Ruben Hinojosa in the Rio Grande Valley. The Valley, of course, is a Democratic stronghold in the state, making her mission roughly as challenging as the one that Republican hopeful Tim Westley faces. “You have to accept that you may lose, but if you’re going to do it, you’ve got to do it good, and you’ve got to do it in a way that raises people’s standards for what they expect from a congressman,” Tijerina says. “I want to raise people’s expectations. We have zero expectations in the Valley for our policymakers.”

All of that is compelling, and it speaks to some of what’s interesting about the Green Party Convention. Some of them might go on to pursue politics further; others, if or when they lose, will take other paths. (Tijerina, who’s worked most of her life in nursing, says that the Sanders campaign that inspired her to pursue politics and go to law school.) In either case, there’s room for alternate ideas.

The main criticism aimed at third-party voters is that they’re wasting their votes. There’s certainly an argument to be made there—more on that in a minute—but at the same time, self-government is fundamentally a creative endeavor. If a third of a percent of the electorate is more interested in seeing what new ideas come up when people get together to do some of the starry-eyed dreaming, is it fair to begrudge them for it?

That’s the most optimistic spin on what goes on at a third-party convention like the one the Greens held in Houston, anyway. The other part of it, though, is that people are angry. That’s a hot emotion in American politics right now, of course—anyone who saw Rudy Giuliani deliver an RNC speech with the passion of a man whose head is moments away from rotating 360 degrees can attest to the fact that alternative parties don’t hold the exclusive on that one. But there’s an inherent tension between the optimism of a party whose main pitch is “vote your hopes, not your fears,” but also often expresses that hope and optimism by suggesting that the people who haven’t joined them are either ignorant or corrupt. There was a lot of talk about how “they” want to hold you back—a “they” that could alternately be the Democratic Party, the Republican Party, corporations, the media, the local school board, etc., depending on the context—and the implicit self-congratulations on being in the fraction of a percent of the population that sees through the scam.

Jill Stein, in her acceptance speech, was more than welcoming of Bernie Sanders supporters. She spoke of how the Sanders movement “merged” with her campaign, and an “alliance” with Sanders’ voters (which may be news to the 70 percent of supporters who told CNN after the DNC that they’d support Clinton, compared with 10 percent who said they were looking to Stein). But keynote speaker YahNe Ndgo, during her speech, read an article by Black Agenda Report’s Bruce Dixon declaring that Sanders was a “sheepdog” designed to “herd” voters to Clinton, working for the system he claimed to be working against. Ndgo told the crowd that they “wouldn’t like” what she had to say about Sanders, but they sure cheered her on for saying it.

In other words, the optimism of the Green Party can pretty quickly turn into something indistinguishable from cynicism. On Friday morning, during the candidate press conferences, one Texas Green who said he was running for office in Travis County (though he wasn’t on the ballot) began an impromptu tirade against Stein herself, declaring her a “petty, bourgeoisie twit” before chanting “Ga-ry John-son! Ga-ry John-son!”

Even Ted Cruz didn’t go that far during his RNC speech, but the best example of the tension between the purported optimism and the declared pessimism isn’t when they talk about Sanders as a “sheepdog,” but when Greens talk about the fact that Sanders’ campaign came up short in the primary. While the revelations from the DNC hacks confirmed that there were people working inside the Democratic Party who were pretty tired of Bernie Sanders come May, Sanders’s own press secretary stridently insisted that “no one stole the election” from her boss—a position buttressed by the fact that Clinton won the popular vote by more than three and a half million people. Still, talking to Greens about the Democratic Primary leads to declarations that the 2016 campaign was proof that the system was inexorably broken.

“We have all of these supporters of Bernie Sanders who believed that political renewal and revolution was possible within the Democratic Party, and the Democratic Party told them ‘no,'” McLarty says. “The Democratic Party is not going to be rehabilitated. It’s not going to be rescued from its corporate sponsors.”

That’s a strange and pessimistic way to view what happened, though. In every contested election, somebody has to lose—regardless of if the DNC preferred Clinton to Sanders, the party isn’t the one who told Sanders supporters “no,” it was their fellow voters. But rather than view it as a success that a candidate whose platform is so similar to their own won over a staggering 12 million voters (an almost 2500 percent increase over Jill Stein in 2012), a lot of Greens see the fact that his success didn’t sweep him all the way into the White House as proof that the game is rigged.

Running on a boldly progressive platform as a Democrat can get a candidate 12 million votes and within spitting distance of the party’s nomination for president; running on a similar platform as a Green can get a sliver of a percentage of the electorate. Yet the folks who convened in Houston view the former as an unfair loss that proves there’s no point in trying to change the system, and the latter as a noble effort that proves that someday the rest of the country is going to come around.

All of which made the Green Party’s convention an example of the politics of weirdness as much as anything. Even people who consider the vast majority of their fellow Americans to be “sheep” like to find somewhere they can fit in, after all. “I was a weirdo when I was a kid.” Tijerina, the congressional candidate from the Rio Grande Valley, declared during the press conference for Texas candidates. “Now look at me—I’m in a room full of weirdos.”

The question about whether the Green Party actually matters in 2016 is tough to answer. To the 500 people who went to Houston, it’s a beacon of hope, even if that hope is often expressed by finding other people who are cynical about all of the same things. As a party, creating space for ideas that are far outside the mainstream certainly has merit, even if a lot of those ideas are unlikely to lead anywhere. It’s a big country, after all, and finding an idea that’s acceptable to roughly half of the voters in it is a challenge that helps explain why progress tends to come incrementally, in fits and starts, and far too slowly to satisfy anybody who gathered in Houston this weekend. They have the opportunity to register their dissatisfaction in November, though, and they’re almost certain to be joined by hundreds of thousands (or more) of their fellow citizens when they do. The Greens matter to them, at least.