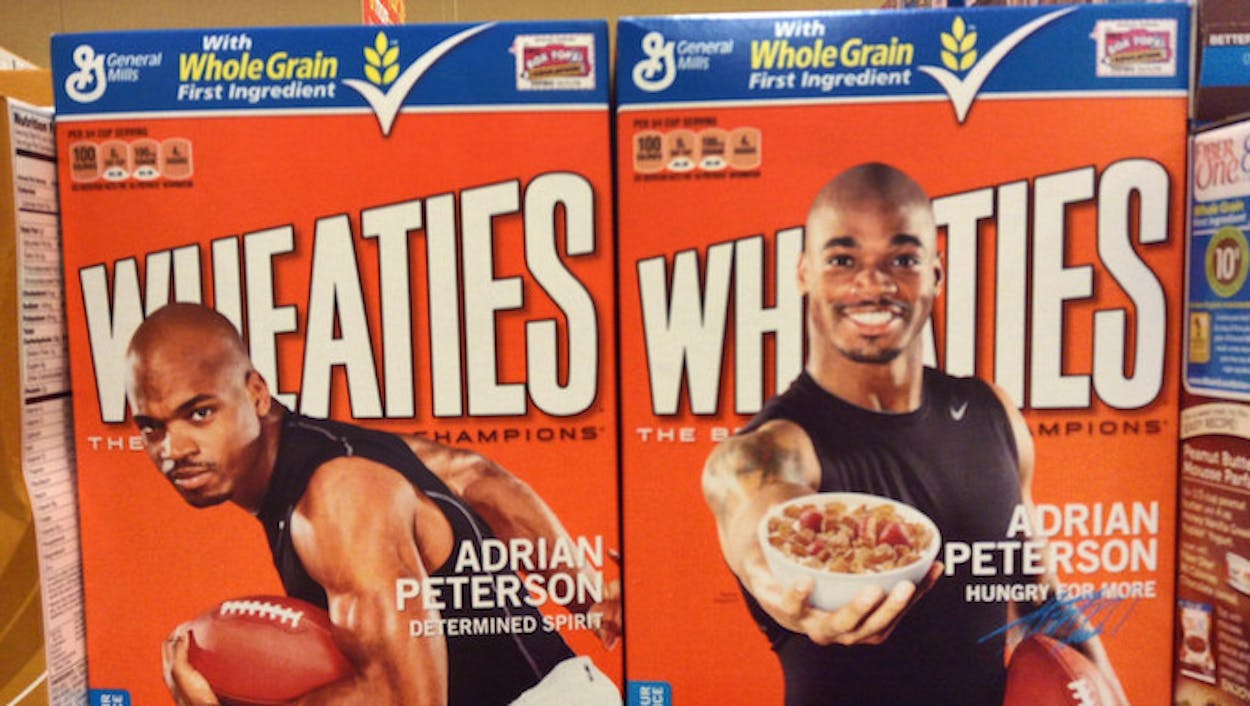

NFL star running back Adrian Peterson, who is still at the moment a member of the Minnesota Vikings, was reinstated by the league on April 15th. He spent last season on the commissioner’s exempt list—a form of suspension—following charges of child abuse in Montgomery County, Texas, which came after photos and accounts of Peterson’s disciplining his four-year-old son with a beating emerged. Peterson pleaded guilty to a reduced misdemeanor charge, paid a $4,000 fine, and performed eighty hours of community service.

Immediately following his reinstatement, the conversation among NFL circles turned to rampant speculation about his future. Specifically, his potential future with the Dallas Cowboys.

Cowboys owner Jerry Jones has never been shy about his desire to see the Texas native Peterson—the best running back of his generation—spend at least some portion of his career in Dallas, and Peterson’s time in Minnesota seems likely to be at an end. He’s an expensive, aging veteran, and the team seemed interested in finding a way to part with their star player to save money even before his criminal conviction. While the Vikings currently insist they have no plans to trade Peterson, teams rarely telegraph moves like that when they’re trying to create a market. Meanwhile, in Dallas, the Cowboys’ own enthusiasm for Peterson culminated last week in a blog post on the team’s official website with the headline “Point: Reinstated Peterson Would Make the Cowboys Serious Contenders.”

The team’s pursuit of Peterson comes after they signed another player who spent the 2014 season on the commissioner’s exempt list—star defensive end Greg Hardy, who had been convicted over the summer of domestic violence charges. (The conviction was overturned on appeal, after the complaining witness failed to testify.) After signing Hardy, Jones and the Cowboys issued a statement that attempted to address Hardy’s off-field history of violence, and justify the team’s decision to sign him regardless:

“We have spent a great deal of time over the last two days in meeting with Greg directly and gaining a solid understanding of what he is all about as a person and as a football player. A thorough background review of him, involving many elements of our organization, has been ongoing for the last few weeks.

“Obviously a great deal of our study was dedicated to the issue of domestic violence, and the recent events that associated Greg with that issue. We know that Greg’s status remains under review by the National Football League.

“Our organization understands the very serious nature of domestic violence in our society and in our league. We know that Greg has a firm understanding of those issues as well.”

Presumably, if the Cowboys swing a trade for Adrian Peterson, they’ll issue a similar statement about their decision to pick up a player who’s been convicted of assaulting his four-year-old son. This sort of language is extremely common in the NFL, whenever players with a history of violence—particularly domestic violence, the league’s current hot-button issue—are signed by teams who need their skills on the field. (Chicago Bears fans heard it last month when owner George McCaskey defended his team’s decision to sign Ray McDonald, who’s been accused of rape and/or assault three times in the past year.) When a guy plays a position that the team needs help with, the team’s leadership tends to become very convinced that that guy has learned a lesson and is ready to be a model citizen.

ESPN’s Sarah Spain wrote about ways that the NFL could try to ensure that that’s the case last month, arguing that

teams need to speak openly about how they plan to rehabilitate a player who faces serious charges. They need to explain why they think a second chance is deserved and how they plan to provide them with an environment that will help prevent recidivism. It’s not just about pouring money into domestic violence PSAs or creating an advisory panel to discuss policy. If the NFL wants to get this right, a player who has faced accusations of domestic violence or assault should be required to agree to treatment in order to continue with his team or sign on with a new one.

Batterer’s intervention counseling and a peer-to-peer mentor relationship with a teammate or staff member would be a good place to start. If said player is one of the tiny percent of people who has been falsely accused, he’ll get valuable treatment and education he can spread to his teammates and family.

All of those are fine ideas, but they also task NFL teams with being social services providers to millionaires. Sports teams love to talk about themselves as being partners in the community—it increases loyalty, and when it comes time to ask for public money to build a new stadium, it’s helpful rhetoric—but the people who sign the Greg Hardys and Adrian Petersons of the world don’t do so because they are deeply passionate about the idea of second chances. They do it because they need a pass rusher and an upgrade in the backfield.

In other words, the risks to the team of signing a player with a history of violence are nebulous and PR-related, while the rewards are very clear: “Reinstated Peterson Would Make the Cowboys Serious Contenders.” Nothing is better for PR than winning football games. (Witness the way the New England Patriots can be accused of cheating multiple times, can be led by a quarterback who left his pregnant girlfriend for a supermodel, and can have a former star tight end be recently convicted of murder, and still be one of the league’s best-loved teams.)

Rather, the real risks of bringing players with a history of off-field violence to town are borne by the people who live in those cities. When Greg Hardy was with the Carolina Panthers, he was accused of assaulting a woman who lives in North Carolina. If another accusation occurs when he lives in Dallas, it’s the women of the Metroplex who are presumably at risk.

As long as the risk to the teams who sign players with a history of violence are minimal, and the rewards have vast, on-field, game-changing potential, there’s no incentive for teams to take charges like those that Hardy has been accused of and Peterson has been convicted of seriously. But what if there were another way?

No one likes the idea that there should be no second chances, and we wouldn’t advocate that players who’ve been accused of crimes be banned from playing the game even if it were possible. But the NFL is certainly capable of holding teams accountable for who they sign—in ways that carry the same real, on-field consequences that bringing them to town does.

A player like Hardy or Peterson (or Ray McDonald, or Ray Rice, or Ben Roethlisberger, or any of the other players who’ve faced accusations of rape or domestic violence) could go on a list like the one the league keeps of players who’ve tested positive for marijuana or other substances. And if those players are credibly accused again, the team who’s signed them could face severe penalties: say, the loss of a first-round draft pick.

That’s a serious consequence, but it’s not an overly harsh one. After all, Jerry Jones “understands the very serious nature of domestic violence in our society and in our league,” and knows “that Greg has a firm understanding of those issues as well”—and if he’s possessed of such confidence after meeting with Hardy, it’s hard to believe he wouldn’t be willing to put a potential first-rounder on the line.

Jerry Jones is asking the people of Dallas to trust that Greg Hardy is a changed man. If he’s willing to risk a first-round draft pick, then we might be willing to believe him. We could at least rest assured that Jones would do everything in his power to ensure that Hardy had access to all the resources he could need to make sure he’s never again in a domestic violence situation.

A policy like this would presumably be popular with leadership at the NFL, which needs star players like Greg Hardy and Adrian Peterson in the game, and also needs to be very conscious of the damage it does to their brand when those stars are revealed to have used their size and strength to hurt people off the field. The league’s current approach to the issue has been widely criticized as patchwork and arbitrary, with Commissioner Roger Goodell doling out suspensions without any clear guidelines. Instead of putting all of that responsibility strictly in Goodell’s hands, though, teams could take it on for themselves, creating what’s effectively a market-based solution to the problem: the coaches and personnel people who know the players best could determine what the most appropriate way to handle a situation is, and fans who know that all decisions are made for football reasons could trust that the decision to sign Greg Hardy, or trade for Adrian Peterson, would be made with football consequences on the line.

Ultimately, whether the league wants to admit it or not, all that really matters to the people who make decisions for NFL teams is what happens on the field. A GM or a coach isn’t going to be fired for signing a guy who’s later convicted of rape, murder, beating a woman unconscious in an elevator, or striking a four-year-old with a stick until he’s bleeding from the scrotum. Those people will be fired if they go 4-12 in consecutive years. Right now, the NFL is mired in hypocrisy and lip-service as it tries to navigate that disconnect. But rather than dance around it, the league should embrace the fact that all that matters is winning—and if a team wants to sign a player with a history of violence, the league can make winning a whole lot harder if they sign a player who reoffends.