My son John Henry and I had just enjoyed lunch at Houston’s venerable 24-hour Tex-Mex eatery Chapultepec on Sunday. The scene in the dining room had been typically Houstonian in its diversity: there were about ten aging hippies across the room—volunteers and employees of KPFT, Houston’s left-leaning community radio station. And at the table next to ours, two black couples were enjoying a late lunch. One of them got up and pumped some quarters in the jukebox, and the room soon filled with Brooks and Dunn, Clint Black, and Alan Jackson, along with a few Earth, Wind & Fire selections.

We paid the bill and left, driving aimlessly through old Houston while my son expressed excitement about his impending entry into the United States Army. He’s headed off to South Carolina next month for boot camp.

Near the corner of Wheeler Avenue and Chartres Street, we encountered a strange scene. The road was all but blocked off by the Houston Police Department, and a throng of people—mostly black—crowded the sidewalk in front of the Lutheran church on the north side of Wheeler. As we got closer, we saw a knot of about fifteen white people in a little pen, surrounded by police. And as we got closer we saw that they were waving Confederate battle flags, and some of them were armed with rifles. Meanwhile, several times as many counter-protestors heckled, chanted over conga drums, and glared.

The group was staging a “White Lives Matter” protest in front of the headquarters of Houston’s chapter of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People.

“We came out here to protest against the NAACP and their failure in speaking out against the atrocities that organizations like Black Lives Matter and other pro-black organizations have caused the attack and killing of white police officers, the burning down of cities and things of that nature,” protest organizer Ken Reed told the Houston Chronicle. “If they’re going to be a civil rights organization and defend their people, they also need to hold their people accountable.”

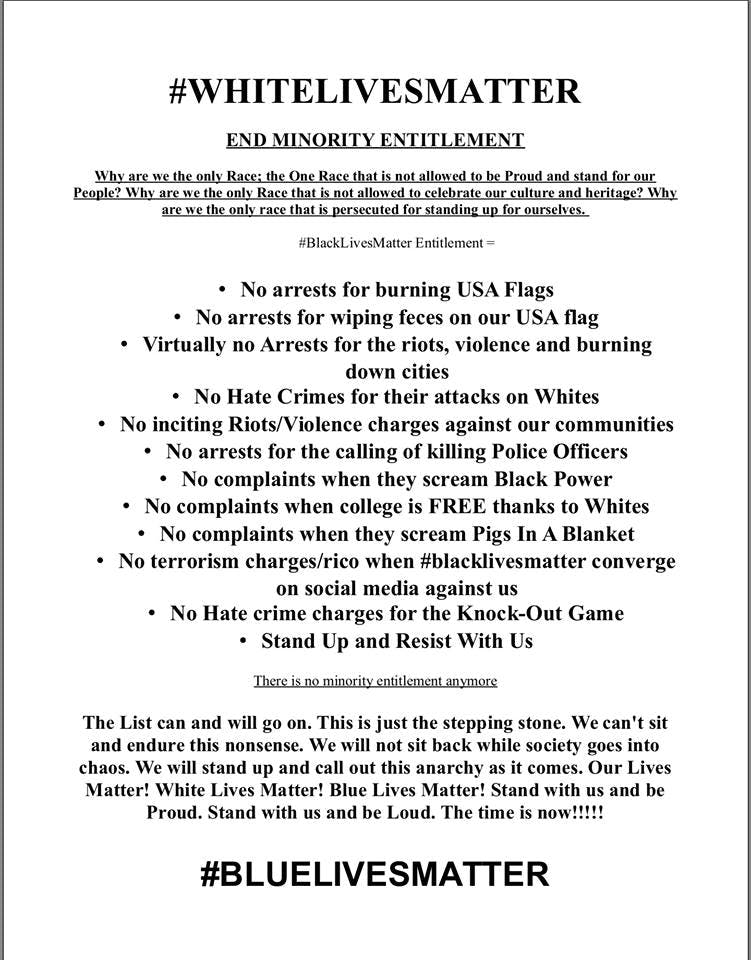

A Facebook page listed some of the reasons for the protest:

There is no shortage of irony in the purpose of the gathering and its location. First, on the event’s official Facebook page, it was billed as “End Minority Entitlement—#WLM.” If the protestors wanted to demonstrate that minorities are overly entitled, the demonstration’s site, right in front of the NAACP building in a section of Houston that is now rapidly gentrifying after two generations of heavy African-American presence, was a poor choice.

Beginning in the 1960s, prospering African-Americans started moving up and out of the Jim Crow Third Ward immediately to the east, into the two- and three-story brick mini-mansions of this neighborhood. By 1985, many Houstonians started thinking of the area east of Almeda as an extension of the Third Ward, meaning it was considered a “black neighborhood.”

That’s not the case anymore. The old brick houses are being torn down and replaced with even larger modern homes, most of which are owned by white professionals. Realtors have renamed it Midtown, an amorphous appellation that covers portions of Third Ward and all of Fourth Ward, the city’s oldest African-American neighborhood, which has now been all but eradicated.

According to Census figures, the white population of greater Third Ward has doubled in recent years, while its black population had declined by ten percent. So the protestors gathered to say that black lives are privileged were doing so in a neighborhood where history demonstrates otherwise.

Not that these demonstrators seemed to have grasped Houston history. Few if any of them were actually from Houston. Tracking down the protestors who gave their names to the media revealed that many of them had driven in from places like Splendora, New Caney, Humble, and Nederland to protest.

As such, they pretty much defined the concept of “outside agitators,” which city leaders across the country love to blame for riots that come in the wake of blatant injustices like the death of Freddie Gray. It was “outside agitators” (usually Communist) who “stirred up” African-Americans at the end of the Jim Crow era, per the white Southern power structure of the time.

But there they were, waving rebel flags, sporting “White Power” t-shirts, and hoisting a “14 Words” banner—a popular white power slogan that means “We must secure the existence of our people and a future for white children.” What’s uncertain is what they were agitating for. Did they think the heretofore silent Aryan warriors of Inner Loop Houston would rally to their cause? Or were they hoping to instigate a conflict? If so, they failed on both counts.

It seemed strange for the protestors to blame the NAACP for not policing groups like Black Lives Matter, who they claimed condoned the killing of white police officers in Houston, of all places. Perhaps they forgot that a year ago Harris County Sheriff Ron Hickman linked Black Lives Matter to the cold-blooded murder of Darren Goforth. “We’ve heard black lives matter—all lives matter,” Hickman said at a televised news conference at the time, District Attorney Devon Anderson at his side. “Well, cops’ lives matter, too.”

Since then, the Goforth case has provided one embarrassment after another for Hickman and his department. The accused gunman, Shannon Miles, had no affiliation with Black Lives Matter—he was a mentally ill person who was able to get a gun and cause a tragedy. In February, he was ruled incompetent to stand trial.

Hickman has not apologized for his rhetoric after that shooting, only allowing that he had “regret” about his assertions about Black Lives Matter, while maintaining his belief that Goforth had been killed solely because he was in police uniform. That could well be true, but the fact remains that Goforth was murdered by a mentally unstable man who was able to get a gun, and we haven’t heard Hickman talk about the role untreated mental illness and easy access to firearms had to play in the tragedy.

That the protestors ended their official pre-event flyer with #BlueLivesMatter seemed to be an attempt at mainstreaming their message. Before the event, organizer Ken Reed posted a video (alongside the daughter Aryanna) stating which flags and banners should be brought: Texas, Confederate, and Gadsden flags, White Lives Matter banners and others reading things like “Faith, Family, Freedom and Future” and that 14 Words slogan, which came courtesy of neo-Nazi David Lane, who died in federal prison in 2007.

“Obviously there’s other symbols that we’ve used at previous rallies—we’d ask you to leave those at home for this rally,” Reed said in the video. “We are trying to reach a more mainstream audience.”

But it seems that they converted few, if any, people. Police outnumbered protestors by the time we arrived, and counter-protestors outnumbered even the cops. But they did attract plenty of attention. The story has since gone national. These couple of dozen outside agitators introduced their imported message, giving Houston an unjustified black eye, and one that plays into the utterly unfounded stereotype that this most diverse and generally ethnically harmonious of American big cities is a racist backwater.