On August 11, white supremacists and neo-Nazis gathered in Charlottesville, Virginia. The group carried tiki torches, chanting “Sieg heil,” and “You will not replace us” (or “Jews will not replace us,” according to varying reports) as they marched through the University of Virginia campus and surrounded a group of counter-protesters who had gathered around a statue of Thomas Jefferson. The night was a precursor to the violence that erupted the next day at the “Unite the Right” rally organized by Jason Kessler opposing a plan to remove a Robert E. Lee monument in Emancipation Park, which once also bore the general’s name.

It’s important to remember that the violence the next day—which left one counter-protester dead and dozens injured—was ultimately about the Confederate monument.

After months of debate and discussion, the Charlottesville City Council voted in February to remove the statue of the Confederate leader from the park. Kessler, who calls himself a “journalist, activist, and author,” organized the rally to protest that decision. A similar tiki torch protest had been held in May, led by Richard Spencer, creator of the term “alt-right.” But last week counter-protesters gathered in opposition, violently clashing with the white supremacists, neo-Nazis, and KKK members who gathered for “Unite the Right.” At one point, James Alex Fields Jr., a man whose former teacher says he idolized Adolf Hitler, drove his car through a crowd of counter-protesters, killing Heather Heyer and injuring dozens others. Two state troopers who were monitoring the protests from above also died when their helicopter crashed.

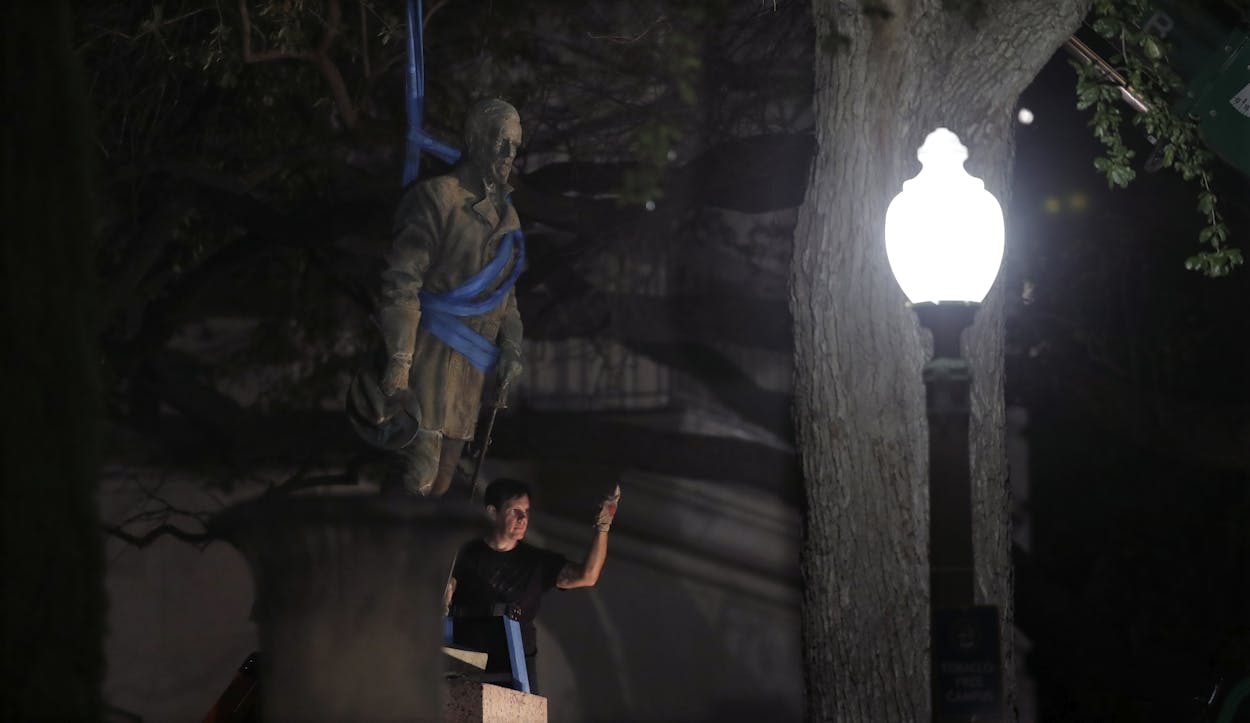

The Charlottesville protests have furthered the national conversation about the presence of Confederate imagery and monuments throughout the United States. Although some localities have began discussing what to do with their Confederate monuments, others have taken swift action. In Durham, North Carolina, protesters took matters into their own hands and toppled a Confederate monument. On the night of August 15, Catherine Pugh, the mayor of Baltimore, took a quieter and more official approach by removing four Confederate monuments late in the night, and the University of Texas at Austin followed suit on August 20. The push to remove Confederate monuments and symbols gained traction in June 2015, after Dylann Roof, a white supremacist, murdered nine black worshippers at Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church in Charleston, South Carolina during a Bible study.

Texas has had its fair share of conflicts over Confederate monuments, particularly at the University of Texas at Austin and the Texas Capitol. According to the Texas Observer, there are about a dozen Confederate monuments located at the Capitol. In 2015, UT Austin removed a statue of Confederate President Jefferson Davis from its prominent position in the Main Mall, the area in front of the UT Tower, and relocated it to the Dolph Briscoe Center for American History earlier this year. The university also quietly removed an inscription praising Confederacy from its location next to the Littlefield Fountain, which is named after George Littlefield, a Confederate soldier and UT regent. Over the weekend, statues of Generals Robert E. Lee and Albert Sidney Johnston and Confederate Postmaster John H. Reagan were removed from the university’s South Mall. These will join Davis at the Briscoe Center, and a statue of James Stephen Hogg, the first Texas native to be governor and the son of a Confederate general, might be reinstalled elsewhere on campus.

The descendants of Confederate leaders have called for monuments honoring their ancestors to be removed from public areas and placed in museums, just as UT has done. Jack Christian, a descendant of Stonewall Jackson, told the New York Times that he was not disavowing his history, but “updating it.” On Tuesday, Representative Eric Johnson tweeted about removing a Confederate plaque from the Texas Capitol.

There have been other calls to remove Confederate statues and rename streets and schools around Texas since Saturday. Governor Greg Abbott weighed in on the matter, stating that “tearing down monuments won’t erase our nation’s past, and it doesn’t advance our nation’s future.” Senator Ted Cruz, said last week that he doesn’t believe it’s beneficial to “go through and simply try to erase from history prior chapters, even if they were wrong.”

President Donald Trump seems to have taken a similar stance. After the violence in Charlottesville, Trump made a statement condemning the “egregious display of hatred, bigotry, and violence on many sides” of the conflict on Saturday. On Monday, he clarified that “racism is evil,” but by Tuesday, he’d doubled back and doubled down on his earlier statements, asserting that not every person rallying against the removal of a Confederate leader were neo-Nazis or white supremacists, and that there were “very fine people on both sides.”

During his press conference on Tuesday, Trump added that those who wanted to remove monuments of Confederate leaders were changing history and culture. He expanded on those views in a series of tweets on Thursday: “Sad to see the history and culture of our great country being ripped apart with the removal of our beautiful statues and monuments. You can’t change history, but you can learn from it. Robert E Lee, Stonewall Jackson—who’s next, Washington, Jefferson? So foolish! Also the beauty that is being taken out of our cities, towns and parks will be greatly missed and never able to be comparably replaced!”

But there’s already revisionist history at play in glorifying Confederate monuments in the first place. The plaque that Johnson wants removed from the Texas Capitol was placed there by a group called Children of the Confederacy, and reads in part:

We therefore pledge ourselves to pure ideals; to honor our veterans; to study and teach the truths of history (one of the most important of which is, that the war between the states was not a rebellion, nor was its underlying cause to sustain slavery), and to always act in a manner that will reflect honor upon our noble and patriotic ancestors.

The Confederacy lost the Civil War—one that they fought in order to continue holding black humans as slaves. Texas, along with other Southern states, made that clear when they seceded from the Union in their Declaration of Causes:

We hold as undeniable truths that the governments of the various States, and of the confederacy itself, were established exclusively by the white race, for themselves and their posterity; that the African race had no agency in their establishment; that they were rightfully held and regarded as an inferior and dependent race, and in that condition only could their existence in this country be rendered beneficial or tolerable.

That in this free government all white men are and of right ought to be entitled to equal civil and political rights; that the servitude of the African race, as existing in these States, is mutually beneficial to both bond and free, and is abundantly authorized and justified by the experience of mankind, and the revealed will of the Almighty Creator, as recognized by all Christian nations; while the destruction of the existing relations between the two races, as advocated by our sectional enemies, would bring inevitable calamities upon both and desolation upon the fifteen slave-holding States.

Confederate monuments celebrate those who fought—and lost—a war to tear apart the United States for the sake of ensuring that they could continue to hold black humans as slaves. Why are those figures, often depicted gallantly gazing into the distance or astride a horse, placed on pedestals in the U.S?

Of the roughly 700 Confederate monuments in public areas of the U.S, 66 of them are in Texas, based on a study conducted by the Southern Poverty Law Center. The study also points out specific time periods in which a majority of Confederate monuments were created:

The first began around 1900, amid the period in which states were enacting Jim Crow laws to disenfranchise the newly freed African Americans and re-segregate society. This spike lasted well into the 1920s, a period that saw a dramatic resurgence of the Ku Klux Klan, which had been born in the immediate aftermath of the Civil War.

The second spike began in the early 1950s and lasted through the 1960s, as the civil rights movement led to a backlash among segregationists.

As Vox points out, this isn’t a mere coincidence, but periods when white supremacists wanted to inflict fear in the black U.S. population. Erecting a Confederate monument is not a benign act to preserve history. People don’t forget historical figures just because there aren’t any statues of them. But when you build a statue—or name a school or a road after something—you’re honoring it. Fenves acknowledged that in a statement about the removal of the UT statues made late Sunday:

Erected during the period of Jim Crow laws and segregation, the statues represent the subjugation of African Americans. That remains true today for white supremacists who use them to symbolize hatred and bigotry. The University of Texas at Austin has a duty to preserve and study history. But our duty also compels us to acknowledge that those parts of our history that run counter to the university’s core values, the values of our state and the enduring values of our nation do not belong on pedestals in the heart of the Forty Acres.

When Roof shot black churchgoers and white nationalists gathered in Charlottesville, they were doing so to uphold what Confederate monuments represent. In the aftermath of the Charlottesville protests, Trump faced criticism and pushback for not clearly condemning and distancing himself from white supremacists and neo-Nazis. But by holding on to Confederate flags, monuments, school names, and street names, the U.S. writ large hasn’t done nearly enough to distance itself from the legacy either.