For the third time in less than a year, a Texas youth has died after contracting an almost invariably fatal brain-eating amoeba from Piney Woods freshwater.

Hudson Adams, a Houstonian working as a lifeguard at Frontier Christian Camp near Crockett, started to complain of headaches and flu-like symptoms three weeks ago. He was first taken to an East Texas hospital, and his condition continued to worsen until the true horror was discovered. Adams was eventually life-flighted to Houston’s Memorial Hermann where he died a few days later.

Last August, the amoeba claimed the life of four-year-old David Charar, who passed away after swimming in a river between Huntsville and Livingston. Later that month, fourteen-year-old Houstonian Michael Riley died after swimming in a lake in the Sam Houston National Forest, also near Huntsville.

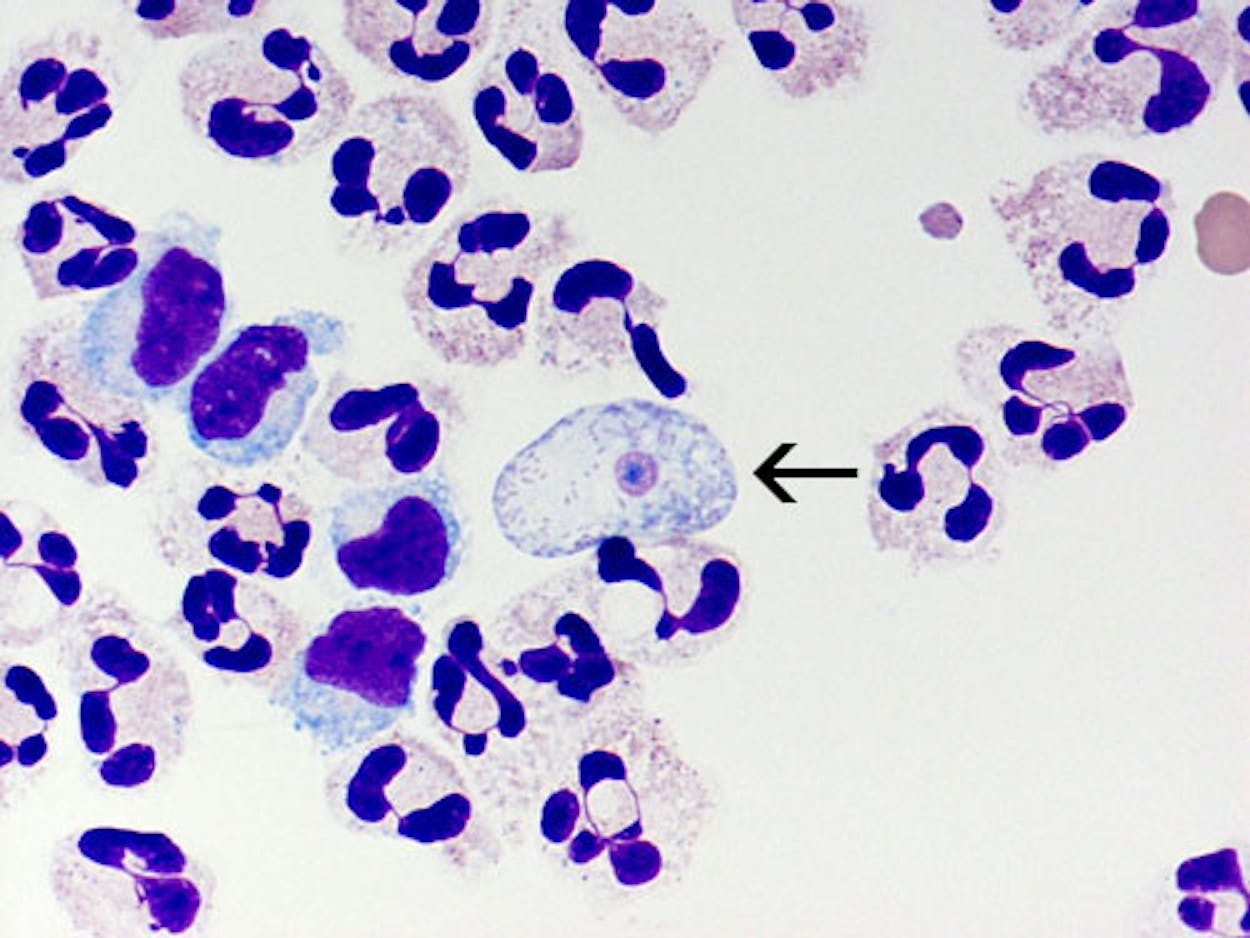

While we’ve all been (justifiably) worrying about flesh-eating bacteria in Gulf waters, a freshwater amoeba has claimed three young lives. That organism is known as Naegleria fowleri, and the infection it causes is primary amebic meningoencephalitis, or PAM. Unlike flesh-eating bacteria, it does not require an open wound to gain entry into your body or a compromised immune system to kill its victims: all it takes is a little contaminated water getting up your nose. Once in your nasal cavity, the amoeba migrates to the brain, which it mistakes for the bacteria it normally consumes.

Risk skyrockets in July and August, falls off a fair bit in September, and almost vanishes for the other nine months of the year. The organism loves warm water—it can thrive in temperatures up to 113 degrees. In cooler times, it lies dormant in the muck in lakes and riverbeds, which is why experts advise that you not stir up any more of that sludge than necessary.

Within that hot summer window, you are most at risk during prolonged heat waves, when the water is warmest and the water levels are diminished. It is not contagious, and you can’t get it from swallowing contaminated water. It has to get up your nose, which happens most often when diving, water-skiing, dunking your head a little awkwardly, or, in some cases, using inadequately treated tap water in a Neti pot.

About three in five victims are thirteen-years-old or younger, and four in five are male. Boys between nine and twelve are most at risk. It is not known if children and males are simply more susceptible to PAM, or if they more commonly engage in the kinds of activities that find them with lake water up their noses.

Prior to the emergence of 2015’s twin fatalities, the Texas Department of State Health Services released a report showing that the state had seen 28 cases between 1984 and 2013—a shade under one a year. With two cases last year and one early in the peak weeks of this summer’s swim season, we do seem to be enduring something of an uptick, which could be caused by any number of reasons: more people frolicking in the stagnant waters of the Piney Woods, warmer waters in general, or just a fluke of fate.

As always, drowning—the danger we’ve grown accustomed to but tend to forget—is far more of a concern than brain-eating amoeba and flesh-eating bacteria. So far this year, 64 Texas children have drowned, which puts us well ahead of the pace of last year’s 75.

Parents would be well-advised to budget most of their water-safety worries in that direction, but save a few for PAM prevention as well. The CDC has a few safety tips:

Hold your nose shut, use nose clips or keep your head above water in warm bodies of freshwater.

Avoid digging in or stirring up the sediment while taking part in water-related activities in shallow, warm bodies of freshwater.

Avoid water-related activities in warm freshwater during periods of high water temperature and low water levels.

Do not put your head under water in hot springs.