The last week of September marks the annual Banned Books Week, in which organizations such as the American Library Association highlight the ever increasing number of books that have been challenged or banned around the world. There seems to be a conservative slant to the books that are most frequently challenged, since a common refrain is that the material is “sexually explicit” or contains “homosexuality.” But even the Bible has been challenged for its “religious viewpoint.”

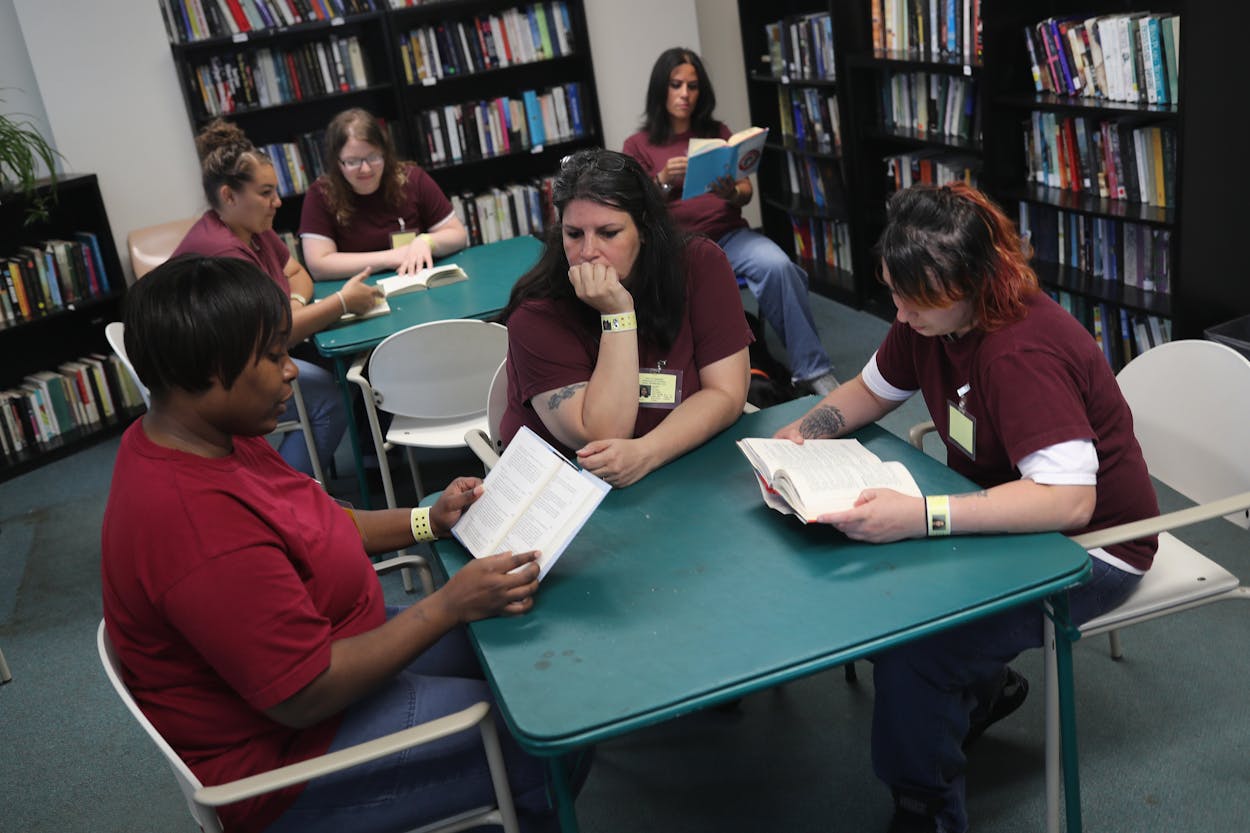

Books are sources of education, enlightenment, and betterment, and—as the American Library Association notes—we should highlight the “value of free and open access to information.” Unfortunately, some of the most systematic censorship of books happens in a place that, in theory, should be focused on the kind of rehabilitation that knowledge can bring: American prisons. And Texas prisons are no different.

After Texas Monthly published an excerpt of Dan Slater’s Wolf Boys: Two American Teenagers and Mexico’s Most Dangerous Drug Cartel last month, the Texas Department of Criminal Justice added the book to its list of more than 11,000 banned publications. The narrative nonfiction tells the story of Gabriel Cardona, who worked as an assassin for a Mexican drug cartel and is now serving time in a Texas prison. According to Jason Clark, a spokesperson for the TDCJ, the book was banned because it “contains information on how to conceal and smuggle illegal narcotics.” The offending section from page 124 reads:

Mario purchased pickup trucks from which he removed panels and lights. The trick was packing the drugs in a part of the vehicle where the body wouldn’t lose its hollow sound when slapped.

That section hardly counts as a how-to manual on smuggling narcotics, but according to TDCJ, it could be instructive in setting up a “criminal scheme,” which is one of the guidelines used in their policy for banned books. According to a 2011 report by the Texas Civil Rights Project, other guidelines for deciding which books to ban are if the book contains contraband; if it includes information on how to make weapons, drugs, or explosives; if it has the “sole purpose” of disturbing a prison’s functionality through strikes, riots and gang activity; if the prison decides the content is harmful to a prisoner’s rehabilitation by encouraging “deviant criminal sexual behavior”; or if it contains “sexually explicit images.”

While some of the policy makes sense—a book detailing the steps to making a weapon probably shouldn’t be in the hands of some prisoners—critics, including Slater himself, argue that the rules are applied so arbitrarily that they do more harm than good. Once a book is banned, it’s banned for all prisons under TDCJ unless a prisoner appeals (without access to the book in question to help build their argument). The appeal is then sent to the TDCJ’s office in Huntsville where the mail system coordinator reviews periodicals while a review committee looks at books and all other materials. A book can only be appealed once, and once it’s banned after an appeal, it can’t be removed from the list unless a prisoner decides to pursue a lawsuit. According to the TCRP’s report, 87 percent of appeals are denied.

One of the major problems of this process is that it is often reliant on personal judgment. When a book lands in the prison mailroom, clerks check the database of TDCJ’s banned books. If the book isn’t on there the clerks scan it for any offending words and content. A book can end up on the TDCJ’s banned book list if a mailroom worker flags it, and the results have been pretty inconsistent.

Women Behind Bars: The Crisis of Women in The U.S. Prison System by Silja J.A. Talvi was banned for a section in which a female prisoner recounted a childhood sexual assault that eventually derailed her life. It was classified as “sex with a minor.” Not censored: Lolita by Vladimir Nabokov, a novel entirely about a man’s sexual attraction to a child. The Arc of Justice: A Saga of Race, Civil Rights, and Murder in the Jazz Age by Kevin Boyle is banned for “racial content” for using the n-word in a section that describes a lynch mob going after African-American men. Meanwhile, Adolf Hitler’s Mein Kampf is still allowed. According to the TCRP’s report, this is the big failure of TDCJ’s policy:

The spirit of the rules is to allow state officials the flexibility to allow prisoners access to literary and educational material, while maintaining the ability to censor materials that would pose a genuine threat to prison security. However, a consequence of this discretion is many arbitrary, unreasonable, and astonishing decisions, as well as regular inconsistencies, largely because material is twisted entirely out of context.

Michelle Dillon, the program director for a non-profit called Books to Prisoners, described TDCJ’s policy as a “slippery slope.” What started out as legitimate concerns has resulted in the banning of 11,000 titles, including classics such as Alice Walker’s The Color Purple. TDCJ’s unchecked censorship is the very danger Banned Books Week seeks to highlight.