According to Elon Musk, there four modes of transportation: Planes, trains, cars, and boats. That’s true, at least as far as crossing large distances are concerned (even a futurist like Musk couldn’t have possibly predicted the PhunkeeDuck). So when Musk introduced the concept of the Hyperloop back in 2012—declaring it the fifth mode of transportation—people were understandably excited by the potential. Musk’s reputation as a forward-thinking inventor had been buoyed by successes with Tesla Motors and SpaceX, and if he wanted to expand the potential for long-distance mass transportation, the world was listening.

Unfortunately, what Musk told us a year later was, in more words, “Here’s the idea, I’m too busy to actually build it.” Instead, he released the plans for Hyperloop as an open-source project, leaving it up to other entities to consider how it would work and to plot necessary improvements. If we wanted to experience the Hyperloop—a form of transportation that would send people traveling in pods through frictionless tubes at speeds faster than any other form of transportation, using technology that’s a cross between a railgun and an air hockey tables—we’d have to figure out how to make it happen on our own.

In 2013, the Hyperloop seemed like a dead concept, which was unfortunate. With a top speed of around 760 mph (roughly 150 mph faster than a Boeing 747) and without a dependence on fossil fuels, the Hyperloop was an exciting thing to have so tantalizingly close. But a funny thing happened after Musk dumped the project on the world: The world kept trying to build it, and Musk stayed involved. Hyperloop Transportation Technologies (HTT), a research group of over 100 engineers, worked on developing it into a feasible plan, going so far as to acquire the resources to build a $150 million test track.

As interest from the scientific and engineering communities in the Hyperloop remained strong, the brainpower behind it galvanized in a competition from Musk’s SpaceX to see who would be building the first test pod to traverse the tube at a speed just under Mach One. That competition was formally held at Texas A&M University over the weekend—at an event that included a surprise appearance by Musk himself.

The event was meant to generate excitement among engineers and the public for the tube-based, transonic, vacuum transport system popularized by the billionaire Musk in 2013. But it was also meant to serve as a rebuttal to skeptics who dismissed the Hyperloop as too fanciful, impractical, and expensive to exist in the real world.

“The public wants something new,” Musk told the attendees. “And you’re going to give it to them.”

The winners at the A&M competition were a group of students from MIT, with the Delft University of Technology in the Netherlands and Auburn University placing and showing in the final results. Which means that one thing is definitely clear here: There are a lot of very smart people who are extremely interested in making Hyperloop a reality, and they’re working hard at it. While we’ll wait to buy our tickets, it’d be downright foolish to bet against them.

All of this is exciting stuff if you’re sick of being stuck in I-35 traffic or tired of the ten hour drive from El Paso to Houston. The future of the Hyperloop remains to be tested, of course—it’s entirely possible that the plans in place won’t work out, and funding remains a gigantic question mark. HTT’s estimates put the price tag on a Los Angeles-to-San Francisco track at around $6 billion (a figure about which experts are skeptical) and a national system is an even bigger collection of question marks—economically, politically, and structurally. (Although an appearance at the A&M event by U.S. Secretary of Transportation Anthony Foxx got people talking about the possibility of federal funding, which could move things along quickly.)

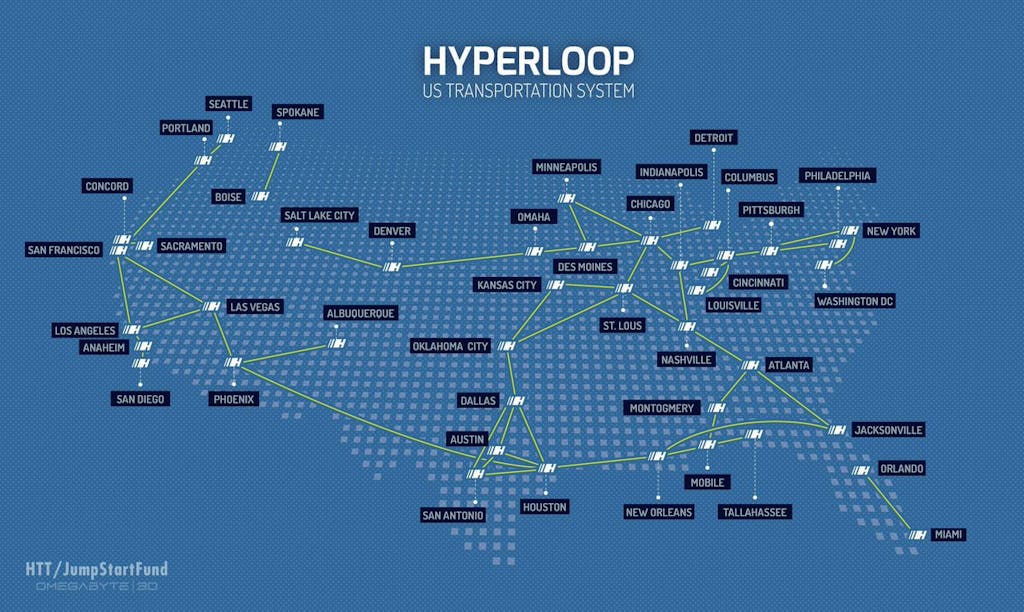

Back in 2014, HTT released a prototype map of a national track. And while the demo map ignores some places (the Houston-to-Phoenix route bypasses El Paso—and all of New Mexico—entirely), the idea of a system that connects Central and North Texas to the rest of the world at great speeds is enticing—and we’ll assume that, at some point, the two million people in El Paso and Juarez who might want to travel on the Hyperloop will get some consideration.

With all of that in mind—and in the spirit of The Future!!! that was at the heart of SpaceX’s competition at A&M—let’s take a look at some of the travel times Texans might enjoy in a Hyperloop-connected world:

Austin to Dallas: 25 minutes

Dallas to Houston: 31 minutes

San Antonio to Austin: 10 minutes

El Paso to Houston: 1 hour, 37 minutes

Houston to New Orleans: 46 minutes

Dallas to Oklahoma City: 27 minutes

Austin to Houston: 21 minutes

Now, these are all estimates based on the pods moving at 760mph the entire time, which is not exactly how the Hyperloop works (like any other form of transportation, it needs to accelerate) so those estimates are probably off by several minutes. But it does give you an idea of how fast this thing is—and the potential world-changing impact of the technology. Whether any of that gets built remains anybody’s guess, in other words, but the fact that the Hyperloop has come this far is downright encouraging, given how unlikely it all seemed even just two and a half years ago.