HB2 was always going to land in front of Supreme Court justices. People on both sides of the issue knew that. While it was still being debated, Rep. Jodie Laubenberg, who co-sponsored the omnibus abortion bill in the House, said that she anticipated that the highest court in the land would respond to an inevitable lawsuit; and though activists rallying against HB2 would have preferred that the bill never passed in the first place, they also knew that the Supreme Court has always been their best chance.

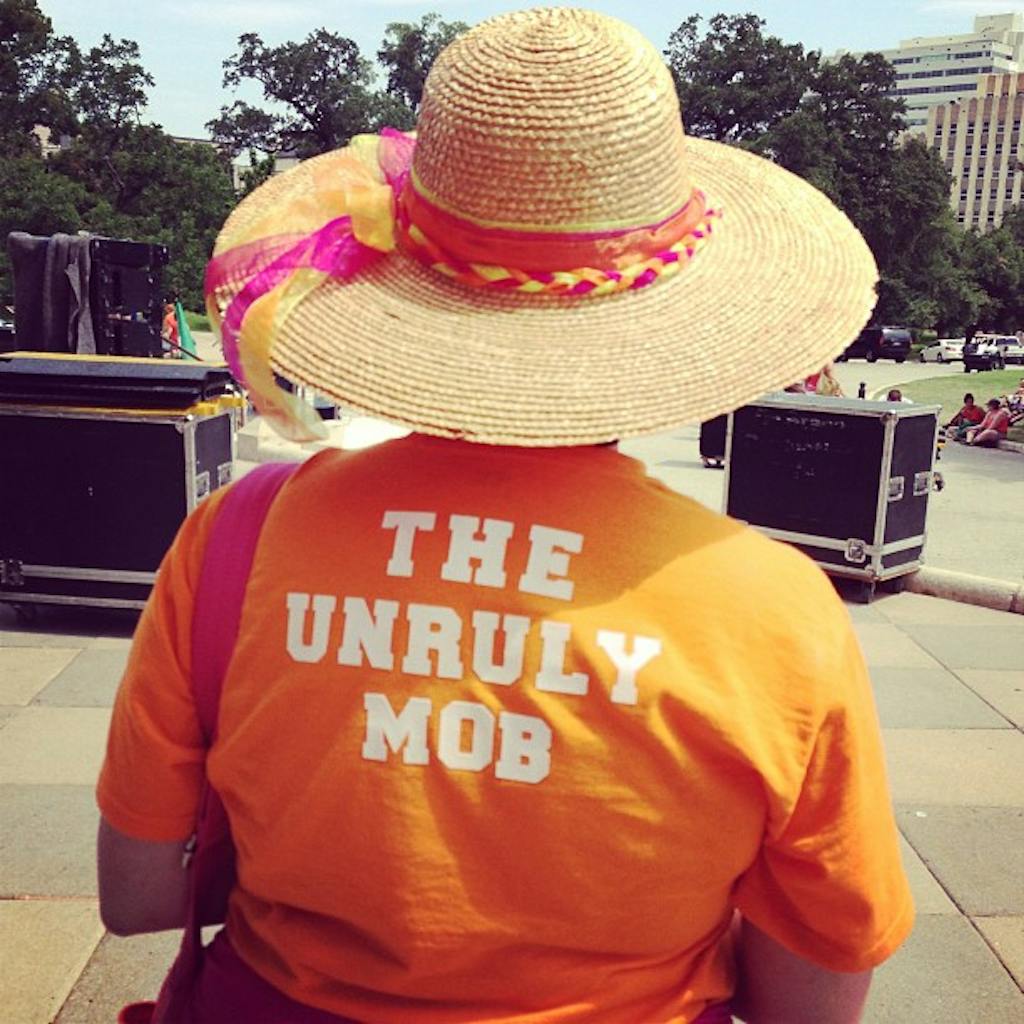

That outcry in 2013 was the most intense that Texas politics had seen in at least a generation. “I’ve never seen—ever, ever, ever—in my entire life anything like the night of the filibuster or the morning after. I’ve never seen anything like the protest on the night when the vote took place in the second special [session] when they actually passed the [bill],” Texas Tribune Editor-in-Chief and CEO Evan Smith said. It made a national celebrity out of Wendy Davis, and brought a generation of activists together under a lot of orange t-shirts and a name given to them by then-Texas Lieutenant Governor David Dewhurst: The Unruly Mob.

At the Texas Capitol in 2013, the Unruly Mob comprised a collection of feminist and reproductive rights organizations, alongside groups like Planned Parenthood and private abortion clinics such as Whole Woman’s Health. Orange became the team color when Whole Woman’s Health printed up t-shirts in the bright hue, and other organizations followed suit to keep things consistent (it didn’t hurt that UT’s colors are orange, which meant that plenty of Austinites already had a closet full of apparel that fit the theme). The Mob, faithfully sporting orange, stayed at the Capitol for nearly three weeks, famously inserting itself into the process on the night of the Wendy Davis filibuster.

Their opponents, meanwhile, opted for the opposite side of the color wheel, decking themselves out in blue. It made for a tense scene at the Capitol—people in orange would wait for the next elevator instead of getting into one filled with people in blue, and vice versa—and ignited passions that had long been dormant in Texas. Democratic State Representatives held a rally on the Capitol steps, each coming out to huge cheers from an audience that likely had never paid attention to them before. Planned Parenthood President Cecile Richards became a fixture at the Capitol that her mother had once overseen. Davis became an icon.

And then it fell off, because that’s what happens with passionate movements—they ebb and they flow. Davis ran for governor, embraced open carry, refused to say the word “abortion,” and got hammered in the election. (A year later, she’d reflect on her mistakes, declaring herself “part of the reason we can’t make progress.”) The coalition of organizations that fought HB2 went back to being individual organizations with their own missions, fundraising priorities, and strategies. Planned Parenthood faced its own challenges, and Whole Woman’s Health became the face of the lawsuit that sent the entire thing where it was destined to end up.

On Wednesday, the Mob returned. While the justices inside the building heard oral arguments on Whole Woman’s Health v. Hellerstedt, a coalition of activists took to the steps of the court, holding a rally reminiscent of 2013 for around 400 participants from around the country. (Twenty feet away, also on the steps, a group of around 60 abortion foes maintained a presence of their own.)

They didn’t wear orange this time. Or, rather, most of them didn’t. In 2013, everyone in orange at the Capitol was there for a single reason: Find a way to fight the bill, even in a system stacked against them. It was a practical fight. At the Supreme Court, though, the goal was more theoretical. Anyone could get into the Texas Capitol, but access to the Supreme Court is limited. There was no hope of influencing the proceedings—it was just about being there. So a few groups had orange signs and shirts—the Party for Socialism and Liberation kept with the 2013 theme, and there were orange signs for Fight Back Texas—while Whole Woman’s Health, the Center for Reproductive Rights, the National Abortion Federation, the National Network of Abortion Funds, and NARAL went with purple. Planned Parenthood stuck with pink, and the ACLU curiously—given the color-coding of 2013—went with blue.

The colors have evolved, and so have the messages. That makes sense—”we need to stop this now” wasn’t on the table, so having speakers who could talk about their work around abortion access in the Rio Grande Valley, or who could explain the importance of abortion rights to transgender men, or who could explain how an abortion fund works was a way to continue the conversation. Inclusiveness was important—not just trans men, but also women of color, and people from different regions. The crowd was made up of mostly native English speakers, but they’d chant “Si se puede!” along with the person at the lectern.

But if the activists who rallied around Wendy Davis in 2013 want to be able to grow their movement, they need to do more than just hold their ground. The unified fight against HB2 in 2013 led to people sharing their abortion stories in an attempt to fight the stigma against people who have the procedure. That could be part of the reason why Hillary Clinton is currently campaigning around the idea of expanding coverage and ending the Hyde Amendment. But with an ever-swelling range of separate goals from pro-choice groups, orange t-shirts might not be enough to represent all of the interests at work.

The rally on the steps of the Supreme Court before HB2 arguments was messy. It ran for hours—the first speakers started at 8 in the morning, and when the hearing ended three hours later it had only grown in size. A lot of the speakers were from Texas, but a lot weren’t. Even Whole Woman’s Health, which was well-represented, now operate more clinics outside of Texas than in.

And then, of course, there was the other rally happening twenty feet away.

The abortion foes still wear blue, and they still look unified. That makes sense—their goals have always been more concrete than the opposition, and the PR battles they’ve fought are less about challenging stigmas or promoting inclusivity and more about convincing people that the procedure constitutes murder and urging politicians to take action. They’re more successful than their opponents on the latter of the two, as well—otherwise, nobody would have been at the Supreme Court to begin with.

The pro-HB2 rally was certainly the much smaller of the two on Wednesday—they were often literally surrounded by their opponents, and they carried blue balloons filled with helium to claim some visual space even as they were outnumbered. At times, things between the two groups heated up—another event that recalled the tensions of 2013. At one point, a speaker in purple discussed the need to end abortion stigma, while a speaker in blue led his rally in a chant of “shame!” At other points, the speakers in blue would respond to things being said by the pro-choice group directly to their own crowd. The testiness went both ways. When the anti-abortion activist responsible for the Planned Parenthood videos, David Daleiden, spoke, people from the other rally marched over to the blue-shirted speakers to chant, “You were indicted!” in a tone that sounded like the bully from The Simpsons.

Ultimately, the future of the fight over abortion in Texas and the rest of the country is unlikely to be less contentious than the past. That’s true no matter what the Supreme Court rules. It’s more clear than ever, though, that what happened in Austin in 2013 is the turning point for the movement that seeks to end stigma around abortion, that fights laws that restrict it, and that wants to expand access to the procedure. Meanwhile, what happened yesterday in Washington, D.C. and in the Supreme Court—and the ruling that comes from it—is likely to define the future for the other side, as well.