The correct immediate response to the spreading novel coronavirus is to prioritize the health and safety of Texas residents. A larger state crisis is starting to boil just beyond the horizon, though. Between the economic downturn that the virus will cause and a growing oil price war between Saudi Arabia and Russia, there could be a multibillion-dollar hole in the state budget by the time the next legislature begins in 2021.

Economic recessions have created these kinds of budget shortfalls three times since the eighties. The first time, with Democrats in power, the state response was major cuts to state programs, with a substantial tax increase to offset some bigger reductions. With Republicans in charge during the last two recessions, state lawmakers relied solely on spending cuts, leading to higher college tuition for students, reductions in state health care programs, and teacher layoffs. The new budget hole probably will become a major issue in legislative races in this November’s elections.

Getting a handle on exactly how bad the impact will be on current state spending levels is difficult. Tax revenue reports from Comptroller Glenn Hegar only go through February, and almost every negative aspect of the virus and the oil price war has occurred this month. At a glance, Hegar’s reports indicate the state is in a healthy financial position, set to end the current two-year budget cycle in the black. The coming crisis will not show up until the reports are in for this month, April, and May.

The state’s major source of finance is the sales tax. Through February, the state had collected $17.5 billion in sales taxes this year, a 15.7 percent increase over the first six months of 2019. (The state’s fiscal year begins on September 1.) The comptroller had estimated that the state would collect a total of $32.7 billion for 2020. If COVID-19 had not come along, Texas probably would have surpassed the estimate. Common sense says that no longer will be the case.

With layoffs in the food service and entertainment industries along with a general economic uncertainty, purchases of major, taxable consumer goods likely will plummet in March and April. Also expect a deep dive in the motor vehicle sales and rental tax receipts, which had been expected to produce $5 billion for the state budget this year.

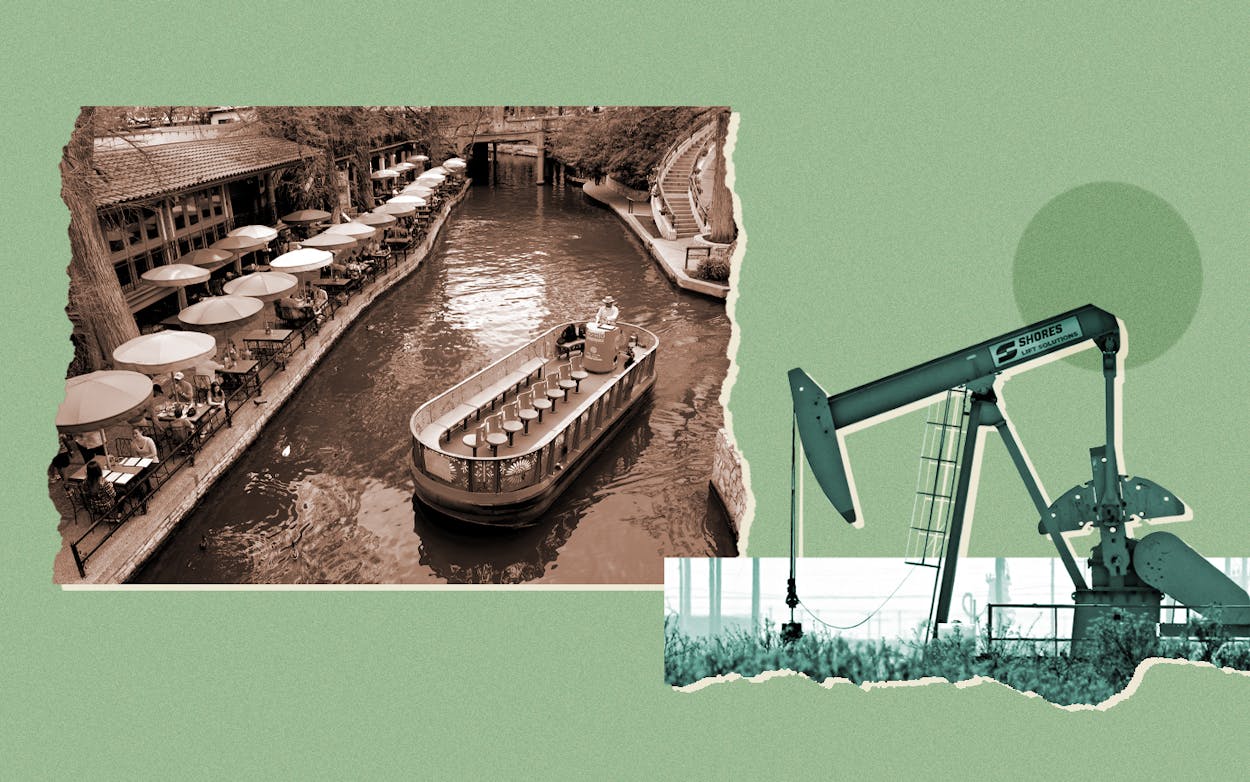

The hotel occupancy tax is tenth among the state’s top sources of revenue, and had been predicted to produce $661 million this year. But the tax will take a large hit from the cancellations of Fiesta in San Antonio, South by Southwest in Austin, the early end to the Houston Livestock Show and Rodeo, the closure of Circuit of the Americas in Austin, and the loss of two major motor vehicle races. The COTA chairman told the Austin American-Statesman that events postponed for the next ninety days represented 600,000 ticketed visitors. Six Flags closed theme parks in Arlington and San Antonio.

Adding to the coronavirus problems is the oil price war that has prompted Saudi Arabia to glut the world oil market in an attempt to take market share away from Russia. The Texas oil and gas industry already was on wobbly footing even before this. While the Texas Oil and Gas Association had bragged in January that the industry paid a record level of state taxes and royalties in 2019, the organization predicted a major slowdown for this year on account of already falling prices and high production rates that had softened global demand. Now, with the price war, a major bust is coming.

For the state budget, that means a major loss in revenue. The oil production tax—the state’s fifth-largest source of general revenue—had been on target through February to produce $3.8 billion for the state this year. The natural gas production tax collections, however, already were 26 percent lower than 2019 and looked like they would miss their projected $1.4 billion in tax revenues for the state by several hundred million dollars this year. Major producers already had been laying off workers in the Permian Basin.

Precisely how bad will this be? We probably won’t know for several months. We can get a feel by looking at some past Texas recessions.

In a similar play for a greater share of the oil market, Saudi Arabia glutted the market in January 1986, causing prices to collapse, taking the Texas oil industry along with it. Prior to the glut, an oil boom had been financing major construction in Texas along with employment. Unemployment rose statewide to 9 percent, banking institutions failed, houses were repossessed, and the Texas economy didn’t start booming again until about 1993.

The oil bust created a $3.5 billion deficit in the state budget. Faced with the possibility of deep cuts to higher education, then governor Mark White declared: “Tough times call for tough choices.” He proposed laying off 4,500 state employees, cutting $750 million in state spending, and temporarily raising the sales tax rate. If state legislators feared a voter backlash, White told them, “Blame me.” The voters did and Republican Bill Clements, who had made the tax increase a major issue, won a second nonconsecutive term in the governor’s office. In 1987, Clements signed into law a $5.7 billion tax increase, the single largest tax hike in state history. A poll that December found that 65 percent of Texans rated Clements’s performance as only fair to poor.

The second big bust to the state budget occurred in the wake of the 2001 terrorist attacks and the recession that followed. The legislative session opened in 2003 with Comptroller Carole Keeton Strayhorn announcing the state was $9.9 billion short of being able to maintain state services for the next two years. Republicans for the first time since Reconstruction had gained a majority of the seats in the Texas House, and they already had a majority in the state Senate. Republican Rick Perry also had won election as governor. To avoid a tax increase, the Legislature cut health care for children, education spending, and funding for the state prison system’s utilities and inmate meals.

All of that was a short-term hit. The longest-lasting change made that year was the deregulation of tuition at the state’s colleges and universities. Instead of the state funding higher education—spreading the cost to taxpayers and businesses across the state—the Legislature shifted the burden to individual students and their families. By the following school year, tuition costs at some state universities had risen by nearly 30 percent. By 2007, tuition was up 59 percent over 2003 at the University of Texas–Pan American, now known as University of Texas Rio Grande Valley. By 2013, statewide tuition rates had nearly doubled from what they had been before tuition deregulation.

The third slam to the budget occurred in 2011 amid the national recession that followed the 2008 Wall Street meltdown. Sales tax revenue declined sharply, and the state finances were burdened with a sizable local property tax cut made several years before when times were good. The legislative session opened with estimates that the state was at least $15 billion short of paying its bills. And anti-government tea party Republicans had made major gains in the 2010 elections. Republicans went from a 76-74 majority in the state House to a 101-seat supermajority. The resulting budget cut at least $4 billion from public education spending, prompting teacher layoffs, and another $1 billion from higher education spending, including financial aid to about 41,000 students.

Party politics played a major role in the budget shortfall debates since the eighties, and there is no reason to believe it won’t again this year even if the coronavirus crisis has passed. The reelection fight over President Donald Trump has dominated the news, but Texas Democrats are primarily focusing on retaking a state House majority before the legislative and congressional redistricting battle that will follow this year’s census.

Now, as the state’s budget woes will come into focus this summer, the November election is more likely to be about state spending and whether Texas will meet the challenge of educating children and providing health care for the poor and disabled, or if the state will fall back to shortchanging our future to avoid even temporary tax increases.

- More About:

- Politics & Policy

- Energy

- Texas Lege