Fort Worth bills itself as “Where the West Begins.” That’s in large part because of a peace treaty signed in the 1840s between settlers and the area’s Native Americans, resulting in an imaginary line drawn through the region to restrict the Native Americans to stay to the west of the demarcation. But the slogan can also apply to the creative efforts of Richard Avedon, the hotshot New York fashion and portrait photographer whose famed series “In the American West,” composed of portraits of hardscrabble Texans as well as individuals from fifteen other states, was commissioned by the Amon Carter Museum of American Art in the late seventies. On Saturday the museum will open the exhibition “Avedon in Texas: Selections from In the American West,” featuring seventeen works from the original exhibition, which debuted at the museum in 1985.

“The show put the Amon Carter on the international map,” says John Rohrbach, the senior curator of photographs, who will give a gallery talk on March 23. “The project brought the museum international acclaim, and still does. And it brought to the museum a project that is now a touchstone in photographic history.”

In the fall of 1978, Mitchell Wilder, the Amon Carter’s director, was brainstorming ideas for an exhibition with Robert Wilson, a KERA-TV executive and consultant for the museum (and father of the actors Owen, Luke, and Andrew Wilson.) Wilder was a photographer himself and was buddies with fellow photographers Ansel Adams and Brett Weston. Wilder and Wilson came up with the concept of documenting the American West not as it had historically been done, through landscapes, but through the people who inhabited it. On a lark they decided to reach out to Richard Avedon, who that same year was on the cover of Newsweek and was the subject of a retrospective at the Metropolitan Museum of Art titled “Avedon: Photographs 1947–1977.”

Avedon agreed to meet with Wilder and Wilson in his New York studio. The women’s rights era was in full swing and the two pitched Avedon a commission to photograph females across the West. Avedon declined but said he might be open to photographing people, regardless of their sex. It was perfect timing: Avedon had just experienced a huge amount of admiration for his work thus far and he was looking to do something different.

Avedon wanted to first test the viability of the project and see if he could operate outside of the safe confines of his studio. On March 10, 1979, he attended the Rattlesnake Roundup, in Sweetwater. There he hit jackpot, coming away with five portraits that would become the basis for the rest of the project. Over the next five years, Avedon—along with his assistant, Laura Wilson, who happened to be Wilson’s wife and had reached out to Avedon after the commission was solidified—took tens of thousands of sheets of film, resulting in 124 portraits.

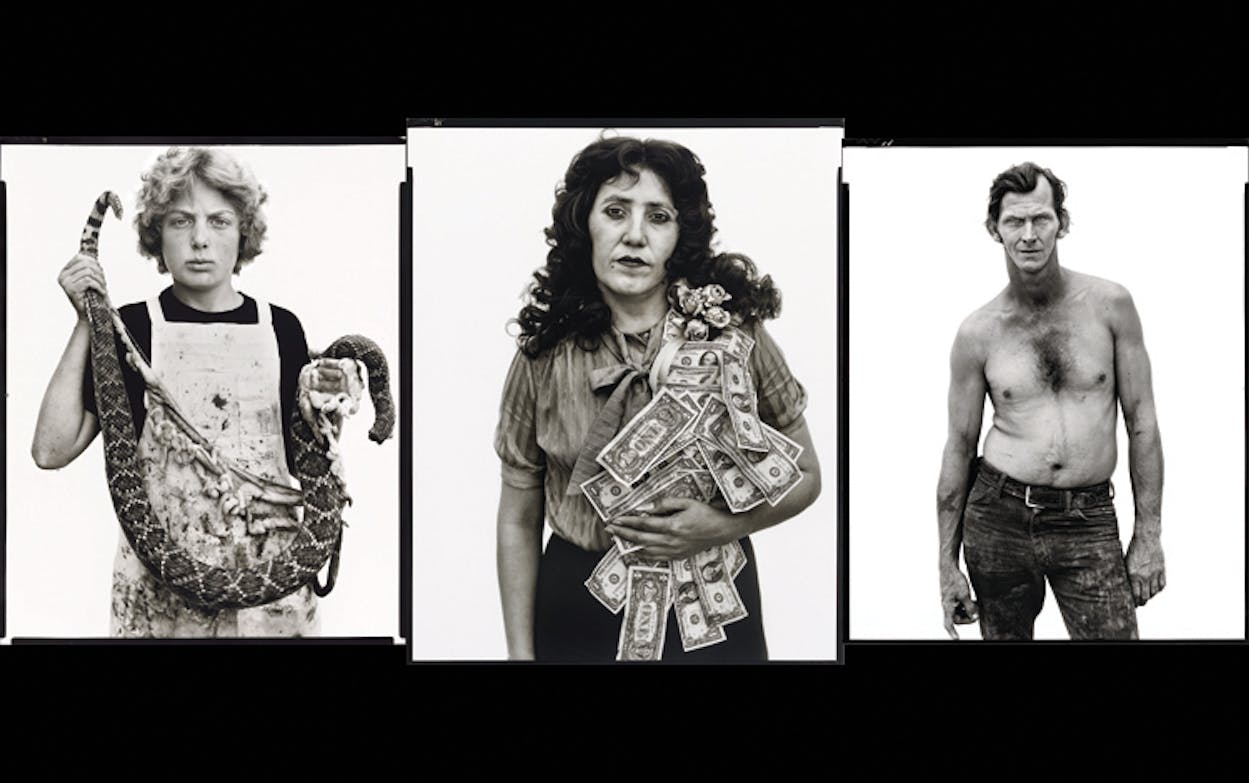

The original show drew some of the museum’s best attendance, but it was met with controversy, which wasn’t entirely surprising. What else would you expect to happen when a New Yorker is tasked with telling Texans their own story? Rohrbach reasons that folks might have envisioned Avedon coming back with images of bankers, lawyers, mayors, and perhaps oil executives, or even celebrities and other public figures who are symbols of life no matter where they live. Instead, Avedon exposed the underbelly of the West. He portrayed prisoners, blue-collar workers, and oddballs, many of them despondent and dirty after a long day of work.

“This is not a romantic view of the West,” Rohrbach says. “People were forced to come in to look at, all across the museum, those people who they’re used to ignoring and passing by, saying, ‘I don’t want to look at you. I don’t need to look at you.’ In some ways, if we’re thinking in very contemporary terms, these are the people that Donald Trump reached out to, who felt like they had been left behind, that the world kept promising things and they were left at the side of the road. And it led to anger. It led to the notion that here you have this wealthy New York photographer coming to the West and making fun of Texas.”

In addition to the original exhibition in 1985, there was another, in 2005. Rohrbach worked with Avedon on that iteration and describes him as a humanist who looked at all walks of life with equal eyes. He was known to check in with subjects well after projects were completed. Rohrbach also thinks Avedon was lonely and says Avedon told him that he saw some of himself in all of the people who made up the series.

Before the exhibition opened for the second time, Avedon died. He was in San Antonio, where he was on assignment for The New Yorker to shoot burn victims at the Brooke Army Medical Center who had just returned from the war in Iraq. Rohrbach says that the anger over the “In the American West” images had subsided by then. Time had secured the pictures a place in pop culture. They were less about context and more about raw power. People were excited to see them. “Every couple of months,” Rohrbach says, “I get people asking, ‘When are you going to put up the Avedons again?”

The pieces in the new show eschew the fifteen other states and focus exclusively on the shots Avedon took in Texas, though not all the Texas images are included. Viewers are introduced to Boyd Fortin, a thirteen-year-old rattlesnake skinner; Petra Alvarado, an El Paso factory worker whom Avedon caught on her birthday after people had pinned dollar bills to her blouse; and Billy Mudd, a shirtless truck driver with scars from stab wounds on his stomach.

It might seem as if it had been hard to gain the confidence of said subjects. These people hadn’t a clue who Avedon was. But Avedon and Wilson, who conducted the primary scouting, persevered. Sometimes they would simply approach people casually walking along the side of the road. And then they would have to convince them to sit for an extended period of time against a white backdrop, with a big-box camera set on a tripod looming over them. But Avedon took his subjects seriously. He befriended them through conversation. He gave them respect. Working with 8-by-10-inch sheets of film, he created portraits as big as 58 by 45 inches and only as small as 41 by 33 inches.

“When you face somebody and they’re your size or larger, right in front of you, and you can peer into their eyes and see Avedon in some cases reflecting back to you, it’s a remarkable experience that just can’t be conveyed in any other way than coming to look,” Rohrbach says. “Avedon’s area of focus is pretty narrow and the sharpest part of the image is the face and particularly the eyes. Because he wants to drive you to those eyes. The eyes are the answer.”

Amon Carter Museum of American Art, February 27 to July 2, cartermuseum.org

Other Events Across Texas

AUSTIN

Down the Hatch

At the fifth annual Austin Oyster Festival, rookies of downing the slippery, slimy bivalves can start at the Fry Bar and try the crispy oyster banh mi, while veterans can start at the Raw Bar, with Gulf and East Coast oysters on the half shell. And then, after a little imbibing and listening to live music, they can meet in the middle: smoked-bacon Oysters Rockefeller at the Grill Bar.

French Legation, February 25, 12 p.m., austinoysterfestival.com

DALLAS

In Full Bloom

Hippies get a bad rap for being unmotivated, but the organizers behind “Peace Love and Flower Power,” this year’s sixties-themed Dallas Blooms—the annual event that USA Today called one of America’s top spring flower festivals—spent almost 12,000 man hours planting 500,000 spring-blooming bulbs across a 66-acre spread.

Dallas Arboretum, February 25 to April 9, dallasarboretum.org

HOUSTON

Voices of our Ancestors

President Trump’s flap earlier this month about the black statesman Frederick Douglass ought to give Nettie Washington Douglass, the great-great-granddaughter of Douglass and the great-granddaughter of the educator and orator Booker T. Washington, more to talk about when she speaks at the 2017 Houston Community College Black History Scholarship Gala.

Hotel ZaZa, February 25, 6 p.m., hccs.edu

HOUSTON

A Skewed Sense of Humanity

The Australian-born sculptor Ron Mueck’s works exist in the convergent worlds of realism and fantasy, at once mirror-image depictions of human beings yet so out of proportion as to suggest the subjects had consumed the “Drink me” potion and “Eat me” cake in Alice in Wonderland. Thirteen of Mueck’s sculptures, about a third of his total output, will be on display at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, as a way to fathom the human condition.

The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, February 26 to April 13, mfah.org

HOUSTON

Sax Men

On paper, the Berkeley-born, Harvard-educated, New York-residing jazz saxophonist Joshua Redman, who will bring his “Still Dreaming” show to Houston on Friday, seems to be everything Texans would turn their noses up at, but consider this: he is the son of Dewey Redman, the great jazz saxophonist who not only played with fellow Texan Ornette Coleman but also went to the University of North Texas, giving credence to the college as a true jazz mecca. Plus, “Still Dreaming” is the younger Redman’s ode to his father.

Wortham Theater Center, February 24, 8 p.m., dacamera.com