Roughly ninety percent of the world’s goods travel by sea. And many of those goods—like cars, grain, and electronics—travel through the Port of Houston, the nation’s second largest port by tonnage. If you’re driving on Interstate 10 towards Beaumont, the port is hard to miss; it sprawls across 25 miles of shoreline. And yet few have any insight into the journey a container of flatscreens, say, takes to arrive at Target.

Enter John Dunaway, the 29-year-old chief mate of the National Glory and his captivating Instagram feed (@abstractconformity), which provides a glimpse into the world of international shipping.

Born in Brazil and raised in Houston, Dunaway comes from a long line of seafarers: his ancestors built sloops on the Trinity River, his great grandfather had a dredging company in Rockport, and his father works as a harbor pilot on the Ship Channel. Dunaway felt the call of the sea himself as a teenager, and headed off for the U.S. Merchant Marine Academy after graduating from Clear Lake High School in 2003.

“I did not want to sit in an office, I wanted to go out and explore,” Dunaway explained recently. “This is a modern day way you can still go out and wander around the world and see things.” He spent a year at sea in college, and graduated with a third mate’s license. Over the last 11 years he’s sailed to 37 countries. Dunaway has been the first mate aboard the National Glory since March, an American-flagged container ship that makes a regular run between Houston and San Juan, Puerto Rico. Among the usual cargo? Forty-nine 40-foot containers full of Budweiser beer, brewed at the Anheuser-Busch plant just three miles north of the Ship Channel. “They’re drinking a lot of Anheuser products on the island,” he joked.

Dunaway began regularly posting his shots from sea a year and a half ago. “I made it a challenge. I told myself ‘I’m going to shoot a black and white photo every day at sea, because nobody ever sees this,'” he said. A mention on Buzzfeed generated hundreds of new followers, and he began doing things like posting coordinates on his images to let new audience to track his journey from home. He said he now selects his photos more carefully. “It’s a 393 foot ship, you’re going to run out of material really quickly. I had to really think about my shots and what am I am going to show people,” he said. (For the six months a year that he’s based in Houston, his feed is given over to land-based Texana, including smoked meats, dancehalls, and duck hunts.)

A selection of Dunaway’s photos with captions in his words follows below:

After a morning shower, a rainbow appeared closer than I have ever witnessed actually emanating from the starboard side of the ship.

A lifeboat sits idle in its davit, hopefully only broken out of the stowed position weekly for drills, but always ready in case extremes were to strike the vessel.

During a monthly inspection of the crane boom, wires, and sheaves, I take a moment to dangle my feet and watch the ocean go by. We wear safety harnesses when going aloft just in case we miss our footing.

Rain or shine, work must continue on a ship. This day we had to go on deck during heavy seas to inspect the lashing of cargo to ensure that none of it had shifted during the night.

After nearly a month at sea, transiting from Houston to South Korea, a pilot boat approaches to embark a pilot whom will guide the vessel into the Port of Busan to discharge our cargo. Every port in the world has pilots, holding the local knowledge to safely guide vessels into its ports.

Ships pass silently as we transit the Straits of Singapore bound for Salalah, Oman. Every day hundreds of ships transit these shipping lanes, the crossroads from the Indian Ocean into the waters of the Far East.

The traffic lanes bypassing the Port of Hong Kong are filled with vessels of varying speeds and sizes, all following the “rules of the road.”

Stacks of containers await loading in the port of Shenzen, China.

Boats filled with a cargo of goats and sheep from Somalia awaited their discharge in the port of Salalah, Oman, after transiting the Gulf of Aden.

While the vessel drifted offshore awaiting its next cargo orders, the crew dropped the fast rescue boat in the water for a monthly drill. We also used this time to inspect the hull and find a bit of entertainment by climbing and jumping on the bulbous bow.

After chipping paint, a sailor pauses to have a cigarette break while the vessel drifts.

As the sun rises, the vessel rounds the small islands of Southern Japan en route to South Korea.

Some ships have far more amenities than others, making them a little more comfortable for sailors as they find entertainment daily while confined to their floating home and workplace. Although small, this pool allows for relaxation and exercise and is filled daily with clean ocean water.

Waves crash off the bow during stormy weather crossing the Pacific Ocean. It takes very little time for the ocean to go from a calm sea to a rough state, yet ships must charge on.

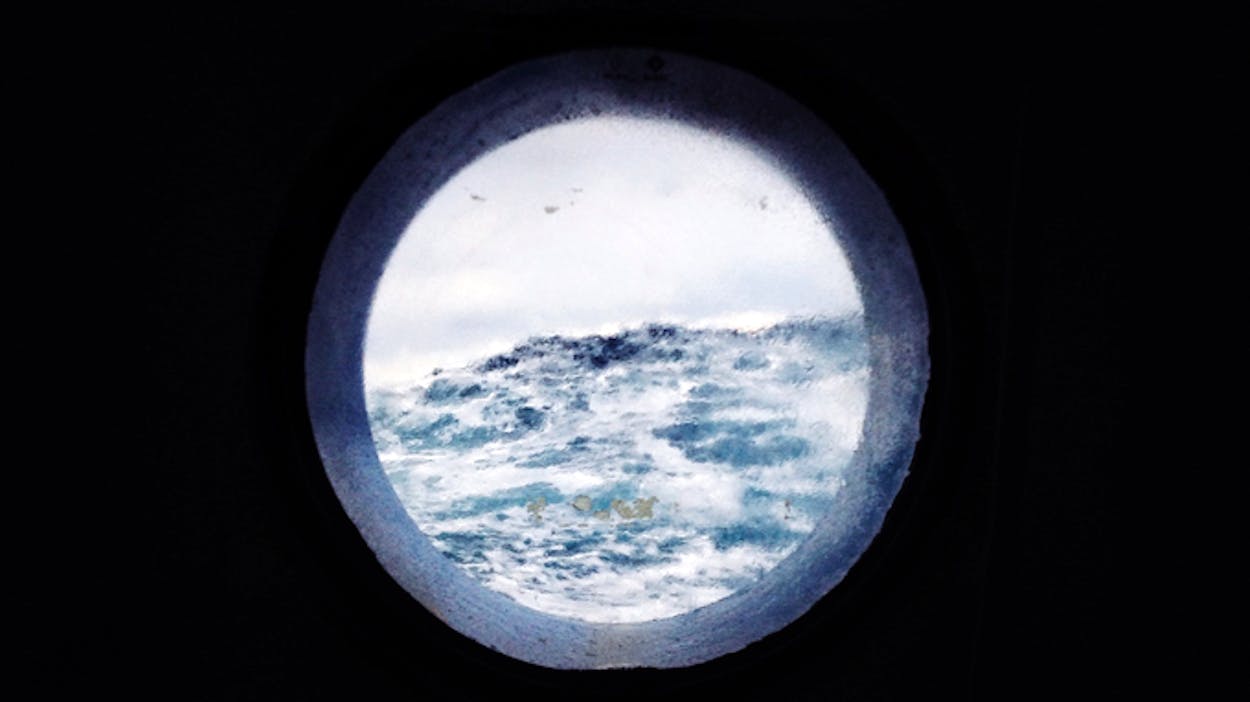

A rough sea, whipped up by a five-meter swell and strong winds, as viewed through a porthole in the galley during breakfast one morning.