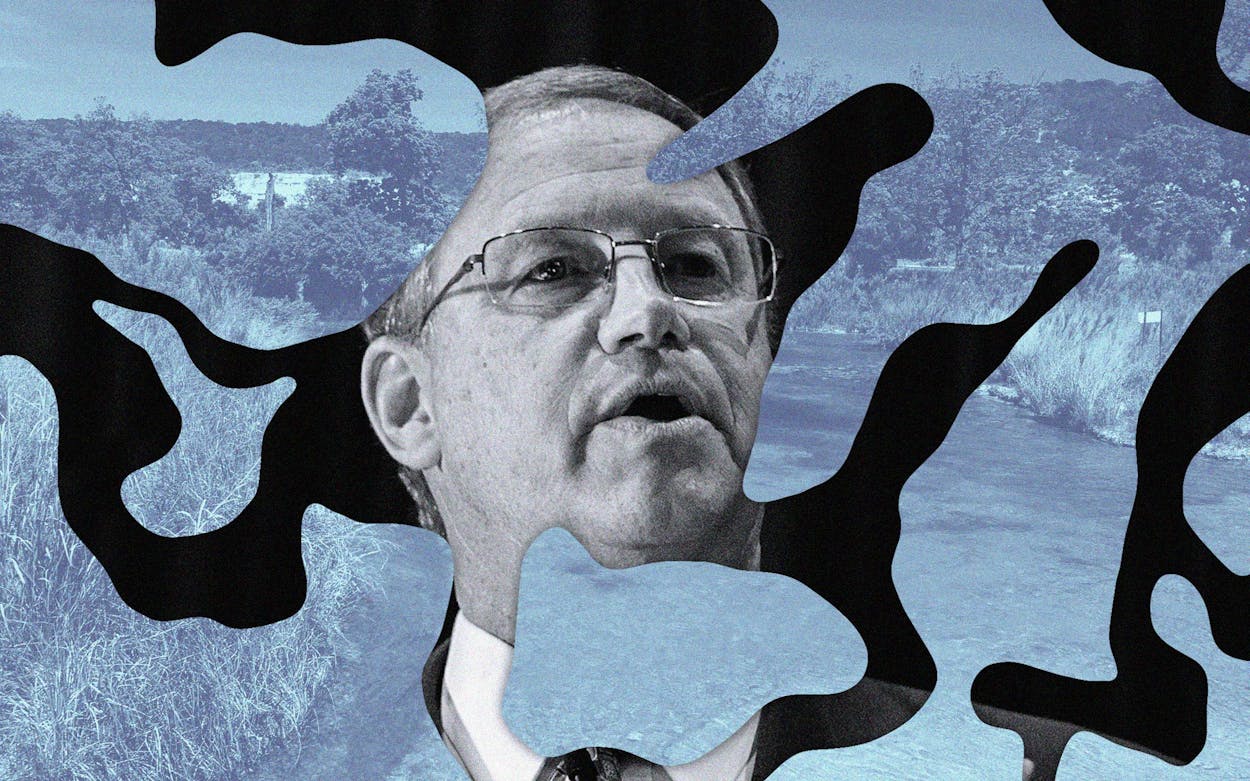

In the midst of record-smashing heat and drought, residents in the Hill Country are battling over who gets to control the flow of a body of water that is running near a historic low. On one side of the fight stands Greg Garland, a wealthy oil executive and donor to Governor Greg Abbott, who wants to dam the South Llano River to create a private oasis. On the other side stands just about everyone else.

At a meeting last week in Rocksprings, 140 miles west of San Antonio, Garland, the executive chairman of Houston-based pipeline and refining company Phillips 66, answered questions in support of his application to build a dam across the river. None of the estimated 187 others at the meeting spoke in his favor. The state’s Commission on Environmental Quality, which called the hearing, will soon decide whether to approve the project.

Garland owns, through Waterstone Creek LLC, nearly eight hundred acres along the river, about twenty miles southwest of Junction. His property includes, according to the local taxing agency, three houses, three barns, a chapel, and a gun range. But he wants to add a private lake. In 2018 his LLC filed with the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality to create such an impoundment for “recreational” purposes. Its concrete dam would stand about seven feet tall, according to a permit filed with the state, and would create a nearly five-acre lake—larger than Austin’s Barton Springs Pool. At the meeting, Garland said the purpose of the dam was to increase water capacity for wildlife and fish. He could not be reached to expound on his plans, and a Phillips 66 spokesperson declined to answer questions on the “personal matter.”

Garland bought the property in 2014, but it doesn’t appear to be his primary residence. He’s registered to vote in Houston. Sitting in a Rocksprings school auditorium as opponents laid into the proposal, Garland looked more rancher than urbane business executive; he wore brown boots, weathered blue jeans, and a short-sleeved, doubled-pocketed plaid work shirt. Patty Schneider Pfister, a Llano County resident whose ancestors have lived along the river since 1847, is one of many local residents who voiced opposition. “Public-use dams are a necessity and they are welcomed,” she said. “What benefit would any private recreational dam be to the community?”

The proposed dam has already cleared a few hurdles. Garland obtained a right to impound water from the Lower Colorado River Authority and a draft permit from the TCEQ. But the privatization of a big chunk of the river does not sit well with local governments. Last year the commissioners’ court in Llano County, a hundred miles downriver, passed a resolution opposing private dams for recreational purposes. Opposition is growing. Last week Texas Parks and Wildlife came out against the dam, arguing it would impact downstream flow, which could affect fish, such as the Guadalupe bass; freshwater mussels; and the public. It noted that the permit would allow Garland’s dam to impound water under certain circumstances even if the South Llano River wasn’t flowing.

This could mean the dam could jeopardize recreation at South Llano River State Park, twenty miles downstream, which draws 65,000 annual visitors. “We are concerned about possible negative impacts to the health and longevity of these natural resources for the enjoyment of the people of Texas,” the parks department wrote in a letter to the TCEQ.

Despite opposition, the proposal has survived challenges for nearly five years and could still get approval from the state. Another public hearing will be scheduled, and afterward a state administrative judge will make a recommendation on whether to approve or deny the draft permit. The final decision rests with the three commissioners of the TCEQ, each of whom was appointed by Abbott. Garland has given Abbott $10,000 in the past two years.

If the commissioners approve the permit, the concrete barrier will join many large dams in the area, some built nearly a century ago under the auspices of Lyndon B. Johnson to bring flood control, electricity, and enhanced recreation to the residents of the Hill Country. But it would stand out from the others: a dam built not for the people, but for a wealthy Texas family.

- More About:

- Politics & Policy

- Water

- Drought