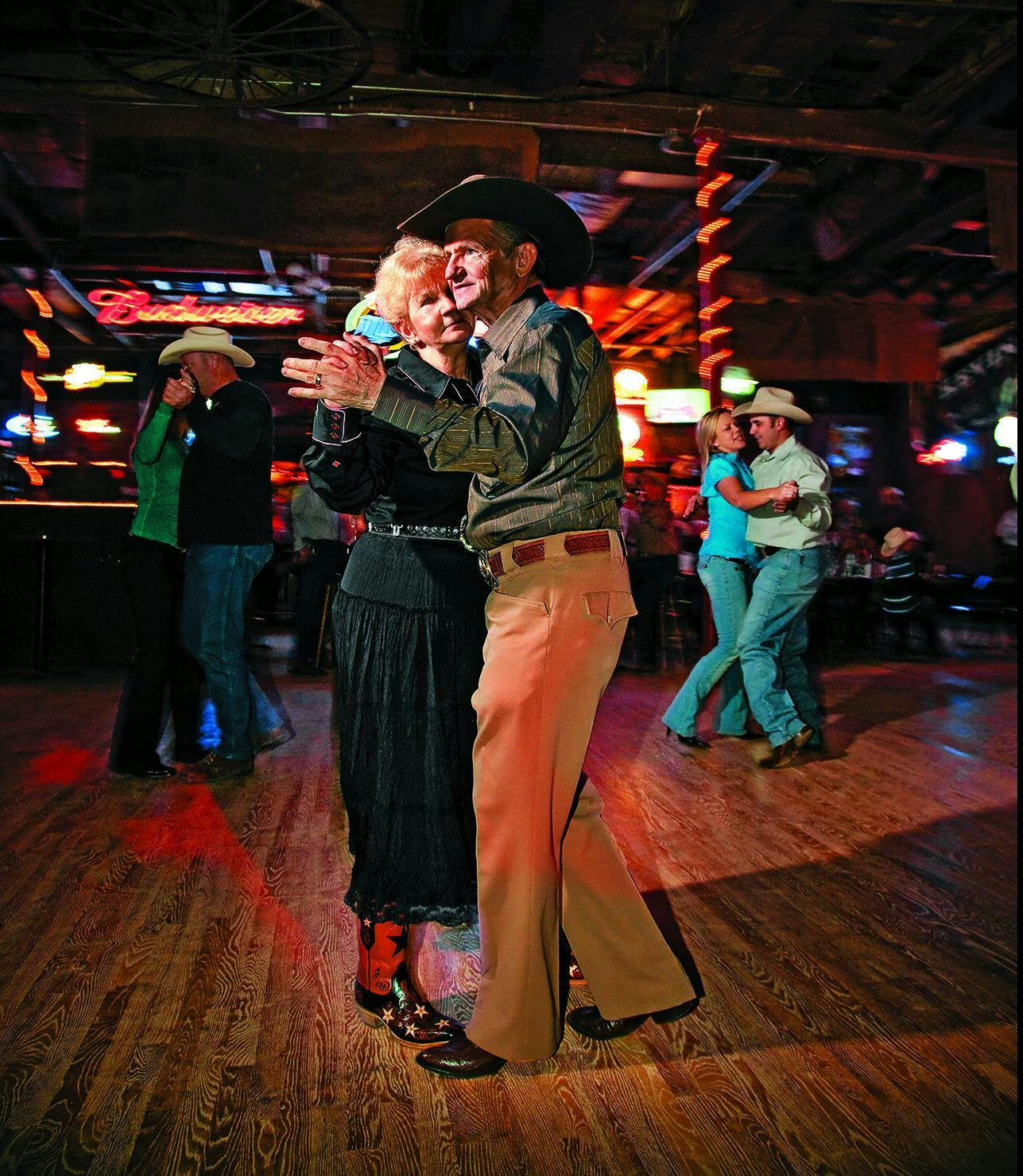

The way to a true Texas dance hall—not the urban simulations, with their cosmetic trusses, last-call footraces, and she’s-mine testosterone—is through the country, a long drive by pastures and cornfields and cattle guards, past driveways that look like roads and roads with numbers for names. You’ll half think you’re lost on the way, then feel a shock when you get there, not at the size of the structure but at the number of trucks parked outside.

An older couple at the front door will take your money and smile like they know you. They’ll gab at length, if you linger, about the bands they saw here when they were kids, dropping names like Adolph Hofner and the Pearl Wranglers, the Texas Top Hands, Johnny Bush, acts you can tell you ought to know better.

You listen, but your eyes go to the dance floor. If the band hasn’t started yet and the floor is empty, you’ll notice the long, dark planks, probably pine or oak, shining from decades of being polished by boot leather. They show none of the proverbial sawdust, just splashes of light reflected from Christmas lights hanging from the rafters. As you scout for an open table along the worn, clapboard walls—where parents pull supper from small coolers and granddads fold brown bags on half-pints and kids itch to go slide on their knees in front of the bandstand—you’ll keep looking back at the floor.

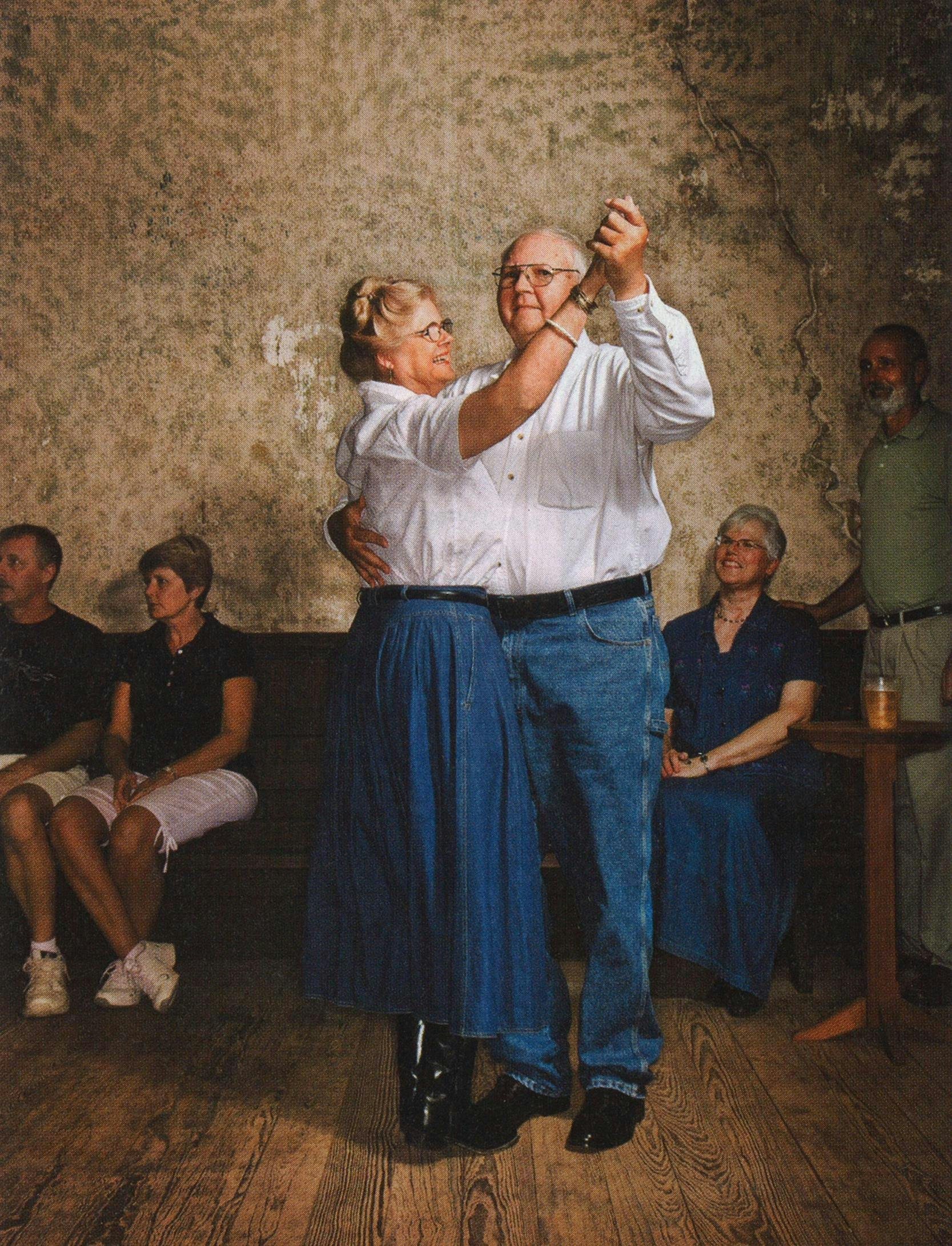

It fills the instant the music starts. The band is probably another you don’t know, maybe Billy Mata or Bobby Flores. No matter what hall or which band, certain songs are guaranteed: “Heartaches by the Number,” “Crazy Arms,” “New San Antonio Rose,” “Corrine Corrina.” Fiddle and steel guitar ring through the room. Songs with different beats drop in and out, “Night in May Waltz” and “Yesterday I Waited Polka.” The band plays “The Cotton-Eyed Joe,” but nobody yells, “Bullshit!” Though some of the songs shuffle and some of them bounce, you realize that all of it’s dance music. That’s the whole point. And when you see a little kid learning to two-step by balancing on her grandfather’s feet, you’ll ask yourself, “Has this always been here?”

The short answer is yes, in a way. The oldest Texas dance halls date to the late 1800’s, built by Germans and Czechs who’d started coming to Central Texas about the time Texas became a state. In Europe they’d lived in villages and farmed fields out in the country. Here they claimed large spreads and lived miles from one another, so the new communities were held together by fraternal orders like the Czech SPJSTs, which sold insurance and loaned money, and the German vereins, or clubs, for shooting and athletics. Every group built a hall, and the hall became the center of life in the New World. On weekends families would ride in for Saturday night dances, bed down under trees afterward, then attend church the next morning. Communities watched whole lives play out there, from baptism to first kiss to wedding to funeral.

The buildings themselves were typically nothing fancy, built by neighbors and designed by whoever provided the lumber. But even the exceptions, like the famous round halls of Austin County, owed their special quality to what happened inside, the festivals and picnics, the sausage and beer, and above all, the dancing. When the Old World ties started to wane in the fifties, the infusion of country music actually broadened the halls’ appeal. Songwriter Robert Earl Keen was raised in Houston in the sixties but spent weekends and summers on his family ranch in Frelsburg, with five dance halls within twenty miles. “From the time I was fifteen to my second year in college, I would go to these halls every weekend. If it wasn’t happening at one, we’d pile back in the car and go to another, burning up two hundred and fifty miles in a night. We’d see regional country bands like the Moods and the Velvets or go to flat-out Czech dances by the Baca Family or Lee Roy Matocha. I saw Ernest Tubb in Hallettsville. You’d just stop at a convenience store, look at a poster in the window to see who was playing, then make your best guess at where the rest of the kids were.”

He describes a period more distant than you’d think. In the past thirty years, dance halls have faded, their constituencies depleted by urban migration, cultural assimilation, and competition from the modern myriad of entertainment options. Few host regular dances; the buildings get more use for antiques shows and storage. And that’s if they’re still standing. A number have been destroyed by fires and storms. Last year they collectively made a list of endangered places, chiefly on the efforts of a nonprofit group, Texas Dance Hall Preservation. TDHP’s mission is to see dance halls revered like county courthouses; its governing principle is that the best way to save them is to use them.

Which is also the premise of this story. What follows are looks at eight classic halls. Note that in the compilation of this list, some hairs have been split. For one, these are not the most famous places. Institutions like Gruene Hall, Luckenbach, and Austin’s Broken Spoke do not want for exposure. Note also that this list is not honky-tonks or nightclubs. Those are places where whiskey and hooking up are as important as music and dancing. (Johnny Bush says that you know you’re in a honky-tonk if you can smell the men’s room.) Though country music is integral to honky-tonks—just as blues is to juke joints and conjunto to cantinas—those are not places where folks take their families. These are true Texas dance halls, places that, on the right Saturday night, you can still take your kids and teach them to dance.

Tom Sefcik Hall

Seaton

Who To See: Jerry Haisler and the Melody 5, Fritz Hodde and the Fabulous 6

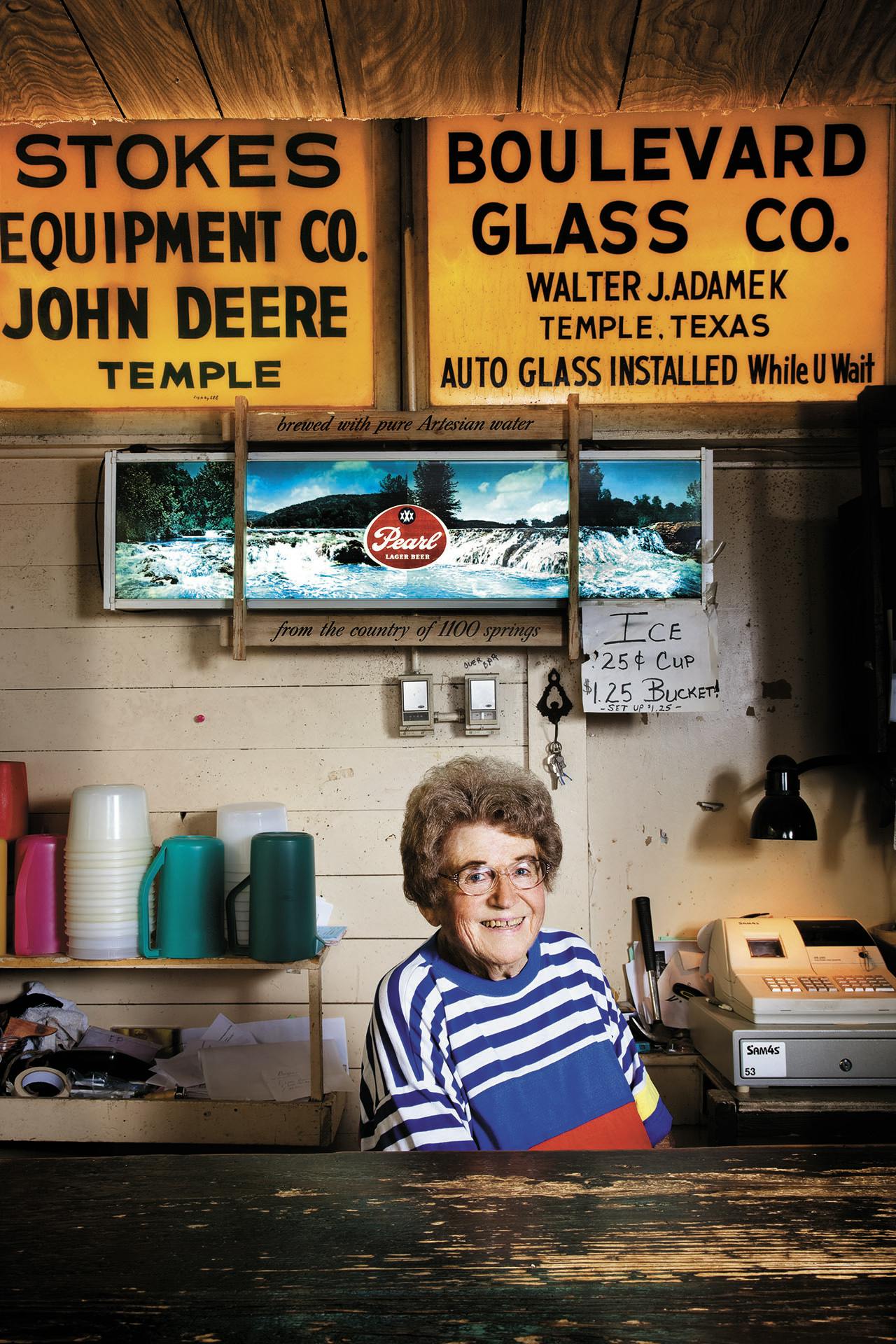

Secret Tip: Ask Alice about her older sister, Adela. They played together in polka bands and, in the late forties, on the Temple Flyers, three-time city softball champs.

There have been only two real efforts to modernize Sefcik Hall. The first came in 1953, when owner Tom Sefcik, who built the white, two-story, clapboard hall in 1923, installed a polished oak dance floor, put chairs ordered from Sears, Roebuck and tables he built himself around its perimeter, and began selling beer other than Pearl. The second came in 1982, when his daughter Alice Sefcik Sulak, who inherited the place in 1971, sealed the open-air windows and added AC.

But stasis sits fine with the hundred-some-odd seniors who brave the pre-ADA stairwell each week to attend Sefcik’s Sunday dances. The music is mostly country, with a few polkas sprinkled in, and couples circle the room under painted-glass panels advertising long-gone local businesses. There’s no longer a “bullring” in the middle of the room, a circle of men waiting to cut in, but the bands still play “snowball dances,” in which couples switch partners mid-song whenever the bandleader blows a whistle. There are also door prize raffles of a six-pack of beer or soda, a ham, and, as a special extra on the Sunday I went, a free haircut from a Waco barber, Columbus Jackson, who was celebrating 53 years of owning his own chair.

Alice, aged “mid-seventies,” is responsible for maintaining the old ways. She was born and raised in the house next door, one of the few left in Seaton, which hasn’t had a post office since 1907 and never saw its population grow above eighty (it’s now around forty). She still plays tenor saxophone at Sefcik one Sunday a month with Jerry Haisler and the Melody 5, a band she helped form in 1966. A tiny woman, she’s barely any taller than her sax.

She opens the downstairs bar daily and runs it by herself. If you happen to be in while there’s dancing upstairs, the sound of their steps will echo through the room like rain on a rooftop, light and steady on the shuffles but like a thunderstorm on the polkas. You’ll also notice a rotary phone hanging on the wall, a dumbwaiter to take beer and ice to the dancers, and a stately bar brought in by her dad from Cameron. “He said he bought it from the Buckhorn Saloon for thirty-five dollars. He couldn’t sleep that night because he thought he’d spent too much money.

“I have a guy who comes in who’s after me to put a sign advertising his lumberyard upstairs,” she said, referring to the advertisements on the cherished glass panels. “I told him I can’t because this is our history. He said, ‘If one ever breaks, keep me in mind.’ I said I would. But we’ve never had one break.” 800 Seaton Rd (8 miles east of Temple), 254-985-2356

Anhalt Hall

Anhalt

Who To See: Gary P. Nunn, Donnie Wavra and the Hi-Liters

Secret Tip: The highlight at the harvest festivals—better even than the pot roast—is the Grand March, a half-hour-long Old World polka.

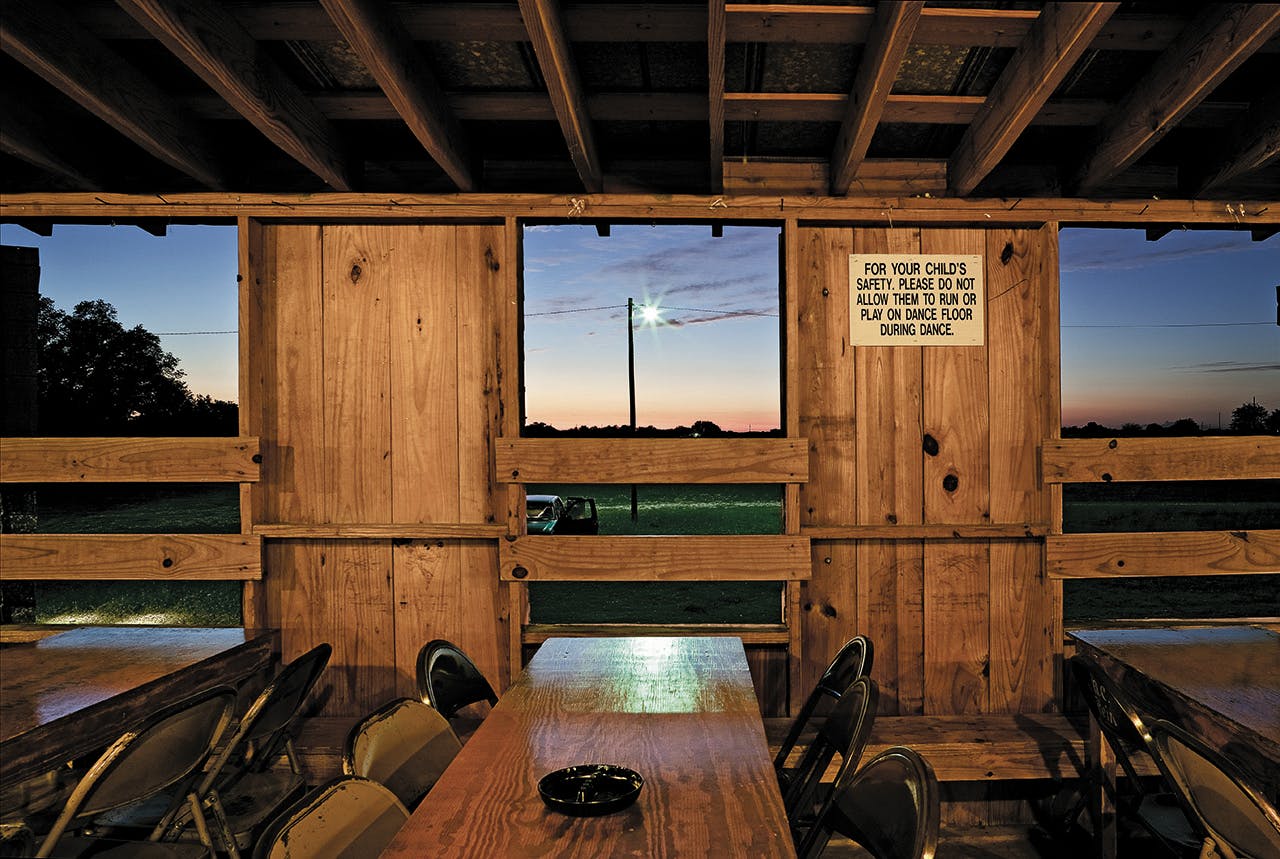

Purists describe Anhalt as the quintessential Texas dance hall. It’s a monstrous gabled barn in a field ringed with live oaks, with a chicken-coop vent on the roof and pressed-tin sheets on exterior walls that are patterned like granite blocks. The dance floor is considered the best in the state: six thousand square feet of dark oak kept perfectly smooth by beeswax polish. Benches, not tables, line the perimeter, and the windows have shutters, not glass. The bandstand extends from the south side of the building, jutting out the back like a firebox on a meat smoker, with a low, curved ceiling to amplify the music. Electricity wasn’t run to the bandstand until 1986.

But the room’s true marvel is its arched trusses. They were the signature touch of builder Christian Herry, who designed Anhalt in 1908 and was, along with Austin County’s Joachim Hintz, one of the two great Texas dance hall architects. (Herry also designed Gruene Hall, though he used conventional trusses.) To curve the wood he soaked long one-by-four slats in water, used mules to bend them around posts in the ground, then stacked them to make them stronger. They span the grand dance floor, stretching to a height of forty feet, making Anhalt feel like a cathedral.

Because the large room was added to an older structure, the members of the verein that owns it still refer to it as “the new hall.” But keeping current has never been a priority here. In the verein’s 134 years of existence, it’s had only eight presidents, and the present one, a stern 85-year-old rancher named Wilton Steubing, still speaks with a noticeable accent. He was born in Texas, but English is his third language, after German and Spanish. He’s been a member since 1952 and in charge since 1992, and his subordinates on the board, men in their fifties and sixties, sound like intimidated teenagers when they describe trying to sell him on even small concessions to modernity, like changing the listing in the phone book from “Germania Farmer Verein” to the easier to comprehend “Anhalt Hall.” But Steubing has little use for newness. When I asked him if Elvis had ever played there, a common, often true claim of many halls, he snapped back, “Hell no. Those rock and roll fans would have tore the place up.”

The old man has eased on other fronts. Though signs on the wall still ban pedal pushers and “indecent, uncommonly dancing,” those rules are no longer strictly enforced. More significantly, he relented on the matter of monthly dances. For Anhalt’s first century it was open to the public only twice yearly, for its spring and fall harvest festivals. But this summer it started booking bands the third Saturday of every month. You should go, no matter who is playing. But don’t expect the lights to dim as you glide along the floor. Steubing doesn’t approve of people dancing in the dark. 2390 Anhalt Rd (24 miles west of New Braunfels), 830-438-2873, anhalthall.com

Quihi Gun Club and Dance Hall

Quihi

Who To See: Billy Mata and the Texas Tradition, Cactus Country

Secret Tip: The rental fee for a wedding is $400.

The beauty of Quihi sneaks up on you. It’s a tin-barn hall in the middle of nowhere, halfway between Hondo and Castroville, at the end of a dirt road lined by live oak and elm trees. The treat comes when you walk around to the entrance: The better part of the hall stretches out over Quihi Creek, supported by dozens of six-foot-tall cedar posts. A friend who grew up in Castroville told me he stole his first kiss under there after sneaking out of a Saturday dance with a girl. It’s unlikely that they were the only couple ever to do so. By his recollection they weren’t even the only one that night.

The dance hall was built in 1890 by the local schuetzen verein (“shooting club”) in a farming community, Quihi, that took its name from the Mexican eagle buzzard. The area never grew much beyond one hundred people, but club membership totals over six hundred—all men, all Germans, and all having resided at some point in Medina County. (A requirement that members be able to read and speak German was dropped in the sixties.) The club still holds a turkey shoot each fall, but its main function now is hosting twice-monthly dances. The biggest comes on Christmas night, when five hundred people attend the D’Hanis High School booster club’s annual fundraiser. For that one, club secretary–treasurer Clyde Muennink, who usually runs the place with just his wife, Kathy, and a couple volunteers, actually hires security.

But there were only about one hundred people there the night I went. A San Antonio band played to a large birthday party for two seventh-grade girls and a handful of couples celebrating date night. I sat with Al and Gin Gray, 80 and 75, respectively, as they sipped on beers and watched kids scoot across the floor where they had enjoyed their first dance. Al described the night, while Gin sat and giggled. “At the end of that first song, she whispered in my ear that if I didn’t dance with her again she was never coming back here,” he said. “She says she fell in love while we were dancing, but I didn’t fall until she called the next day.”

“I didn’t think girls called boys back then,” I said, turning to Gin. “Oh, this happened earlier this summer,” said Al. “We just got married on July 18. This is our two-month anniversary.” Driveway is off FM 2676, 6 miles east of the intersection at Texas Highway 173 (35 miles west of San Antonio); 830-426-2859; quihidancehall.com

John T. Floore Country Store

Helotes

Who To See: Willie Nelson, Ray Price

Secret Tip: The Sunday dances are still free.

Despite the hall’s long association with Willie Nelson, the outsized persona touching everything at Floore’s belongs to its founder and namesake.

John T. was a king in search of a kingdom when he moved to Helotes in the late thirties. He’d just lost a run at the San Antonio mayor’s office, and the first piece of his new empire was a Red and White grocery that he bought in 1942 and ran as a combination market, real estate office, and beer joint. But he’d managed the Majestic Theatre during the Depression, and his background was showbiz. After a couple years watching San Antonians blow past Helotes cornfields on their way to Bandera honky-tonks, he moved to a larger space across the street, painted the cinder-block walls the color of split-pea soup, and added a dance floor. In 1949 he poured a big concrete slab under the oak trees out back and billed it “the largest patio in the Southwest.” His star-lit family dances were a departure for country acts passing through.

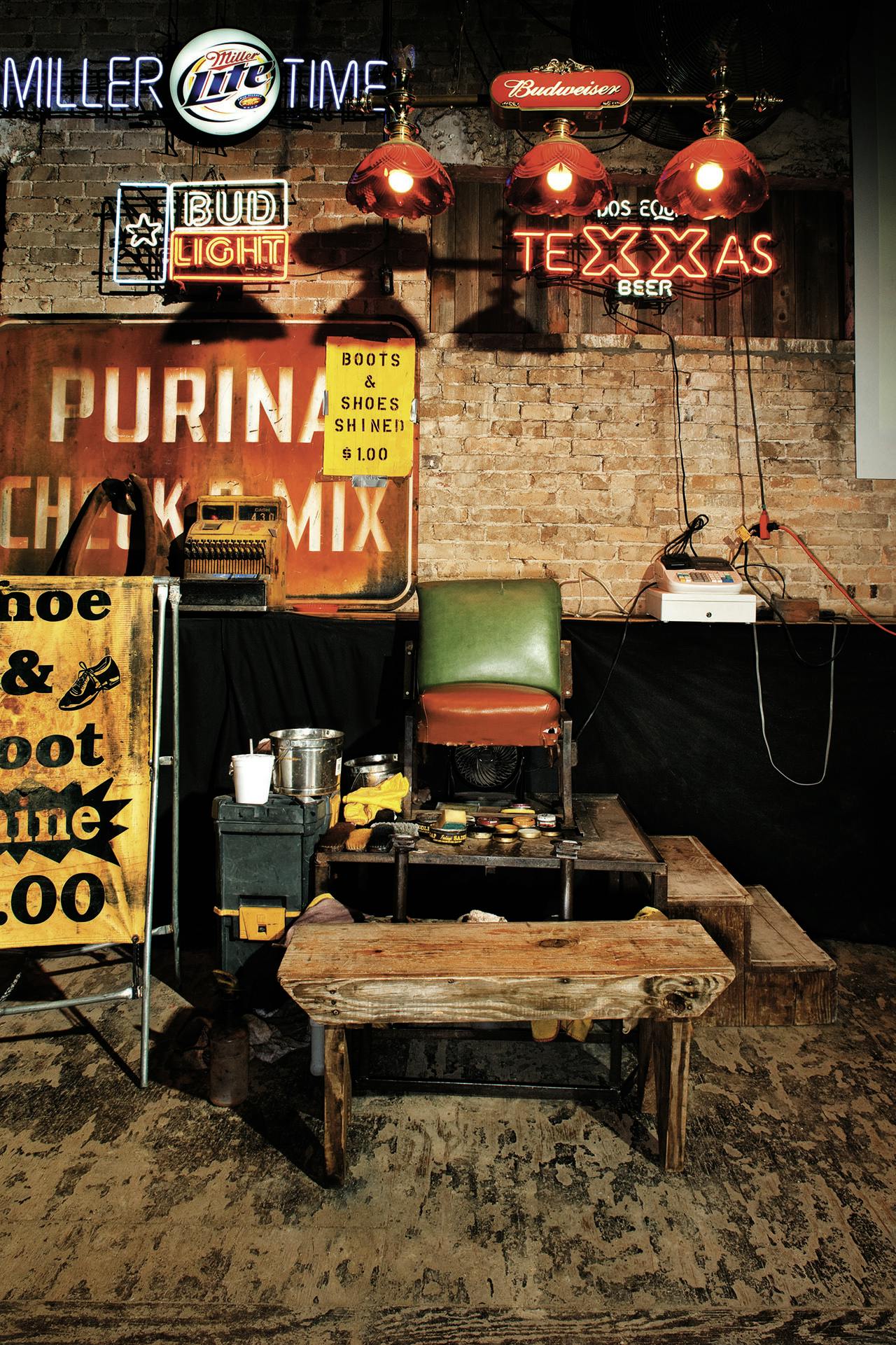

But the real distinction at Floore’s was the man himself, who, despite coming to own much of the town, chose to live in the store’s office, which he shared with his basset hound, Bridget. He was a huge man, some six and a half feet tall and over 250 pounds, with slicked-back hair and thick black glasses. He greeted patrons at showtime in a suit and tie, though if you encountered him during the day, he’d be sitting in front of a swamp cooler in just boxers and suspenders. He made his own rules; selling whiskey by the glass was illegal, so he sold bottles out of a chicken-wire cage near the door that he called a liquor store. He promoted performers by hanging their boots from the rafters and their photos on the walls, along with signs like “If you’re going to drive your old man to drinking, drive him here.”

In the sixties he got tight with Willie, who was then struggling in Nashville. When Willie needed money, he would play Floore’s. And when Willie moved the Family to Bandera, in 1970, John T. served as, among other things, their lookout. If heat was headed their way from local lawmen, John T. let Willie know. He also loaned Willie $5,000 to start his own publishing company. “We later sold that company for $2.2 million,” remembers Paul English, Willie’s longtime drummer.

The outside world knows John T. from Nelson’s song “Shotgun Willie” and its line connecting him to the Ku Klux Klan. The second-most-asked question at Floore’s, right behind “Did Willie really used to play here every Saturday night?”—a reference to another of Floore’s jokey signs—is “Was John T. really a Klansman?” Some old-timers deny it, but others say that when he was growing up in East Texas, that was just part of doing business. And they say that he really did sell sheets to the Klan. They add that he was married two times, to a Native American and a Jew. “The Klan was just another vehicle to sell something,” says Willie’s bassist, Bee Spears, who grew up in Helotes.

In 1973 John T. sold out to his right-hand man, Joe M. Algueseva, with two understandings. First, that he be allowed to keep living in the office, where he would die two years later. Second, that the building never be changed, a condition that has been passed down to two successive owners. The other constant at Floore’s is Willie, who still plays once or twice a year. Seeing him there is one of the greatest pleasures a Texan can know. 14492 Old Bandera Rd (17 miles northwest of San Antonio), 210-695-8827, liveatfloores.com

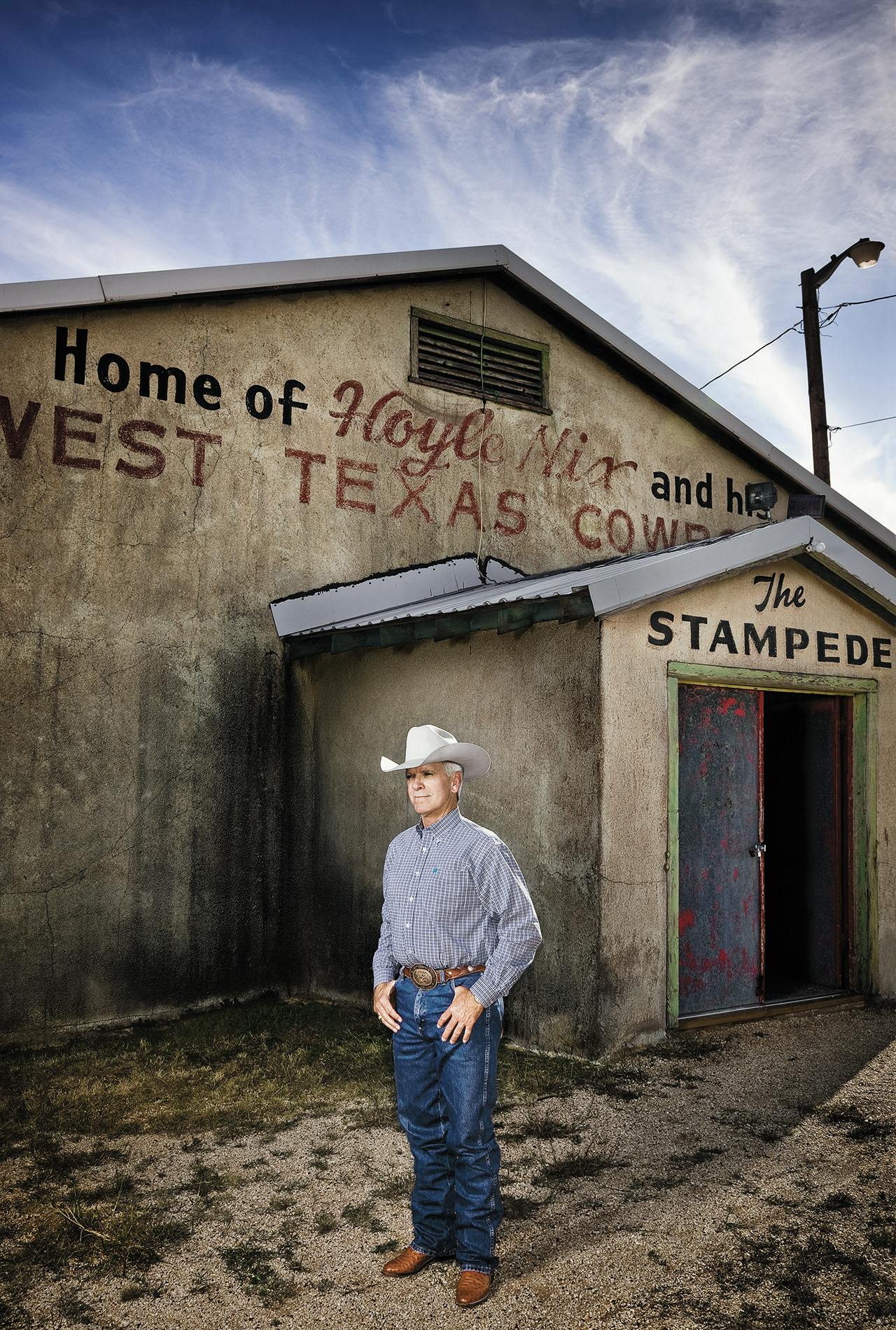

The Stampede

Big Spring

Who To See: Jody Nix and the Texas Cowboys

Secret Tip: Bring your own beer.

The original plans for the stampede, built in 1954 by western swing bandleader Hoyle Nix and his brother and bandmate Ben, called for a ceiling and Sheetrock. But in the rush leading up to opening night, they never got around to finishing it out, and after playing that night to 1,100 dancers, they ultimately decided not to fuss with it—or anything else. The Stampede still has the same raw rafters and bare walls, same propane heaters and Coke box for sodas, same calf-roping mural behind the bandstand. It also still hosts semimonthly dances by Hoyle’s band, the Texas Cowboys, now led by his son Jody, who inherited the band when his dad passed away, in 1985, and the hall when his uncle died, nine years later. “We’ve never polished the floor or smoothed it back out,” says Jody. “You can see ripples in it from years of dancing. But occasionally I drive a nail back down.”

When I attended September’s annual Homecoming Dance, the featured guests were a hundred nostalgic locals celebrating a sixtieth high school reunion. But most of my evening was spent with some hard-core dancers who’d come in from Midland and Ruidosa, not for the reunion but the dance floor. The four Davis siblings and their cousin Russell Welch had been shuffling and waltzing for nearly two hours when I pulled up a chair during their first collective breather. April, aged fourteen, was the only one at the table whose feet reached the floor. The rest of the bunch—Cody, twelve; Brittany, eleven; Russell, seven; and Cacey, six (who had two short blond pigtails sprouting from her head like bug antennae)—swung their feet and fidgeted. Apparently talking about dancing is not as much fun as actually dancing.

“So y’all can all dance?” I said.

“Our grandfather taught me when I was four,” said April. “We all waltz, but I prefer a two-step or a shuffle.”

“What if you wind up with someone who doesn’t know how?”

“I just start over,” said Cody, who wants to be a Marine and a cop when he grows up. “I take my first step this way . . .” he stood and took a step forward with his left foot, “and then three more this way . . .” he demonstrated the shuffle that completes the two-step. “Then I look down to see if their feet are in the right place.”

“If they’re not?”

“I never say they made a mistake. I just start over. They’ll get it.”

As I scribbled some notes, Cacey climbed on my shoulder. “Can you draw a picture of me?”

Before I could explain that I’m not a very good drawer, she was gone, dragging a lucky young buck in a bright-blue cowboy hat—he’d apparently gotten it for his recent fourth birthday—onto the floor as Jody kicked into “Across the Alley from the Alamo.”

“So Jody’s pretty good, right?”

“The older people used to come when his father played here,” said April, “Hoyle Nix. Our mom used to come all the time too. And she met our dad dancing in Lubbock.”

Brittany piped in. “Our parents got married last month and had the reception here. We danced until twelve-thirty.”

“That’s pretty late,” I said, “but it was a special night. Do y’all ever sleep at the dances?”

Each head cocked back, and each face adopted the same sour expression, like I’d just slid them bowls of muesli.

I explained. “There’s this old tradition where the parents would bring blankets for the kids to sleep in the corner when it got late.”

“Um, no,” said Brittany. “We came to dance.”

At that, Cacey reappeared on my shoulder. She looked at the others, and then she cocked her head back too. But she was smiling.

“Oops,” she said. “I just burped in your ear.” 1610 E. Texas Highway 350, no phone, jodynix.com

Club Westerner

Victoria

Who To See: Little Joe y la Familia, Ruben Ramos and the Mexican Revolution

Secret Tip: If you want to eat at the dance, pick up dinner to go at Mumphord’s Bar-B-Q or Fossati’s Deli.

The Westerner is one of the few halls without a wall of fame; no show posters or autographed publicity stills hang on the wood paneling, chiefly because of the hall’s historically split personality. Opened in 1929, it hosted whites-only country dances until 1956, when John Manuel Villafranca, a 31-year-old rural-route postal carrier, talked the owner into letting him lease the place out for Sunday tardeadas, or afternoon dances. As many as eight hundred people would show up each week, Hispanic families from all over south Central Texas who came and danced to orquesta tejana acts like Beto Villa and Isidro Lopez, the Tex-Mex equivalent of big-band western swing. By the early sixties Villafranca was managing the place and had replaced Saturday night’s country bands with conjuntos. But he kept Fridays for the white crowds, for “Teen Age Dances” featuring Roy Head and the Traits and BJ Thomas and the Triumphs, parties that were nominally hosted by a white couple he knew. He’d have tipped his hand if he’d put photos of Mexican Americans on the walls.

Villafranca quietly bought the Westerner in 1965, borrowing $52,000 from a friend on a handshake after being turned down by area banks. The hall was then the centerpiece of an eighteen-acre theme park called Pleasure Island (so named because it sat inside an oxbow flow of water on the Guadalupe River bottom), with a swimming pool, baseball field, and skating rink. Villafranca moved his family onto the property and ran it with his six children, who served as lifeguards, janitors, handymen, and bartenders. Before shows they liked to sneak onstage and play the bands’ instruments. “My brother James usually played drums,” says Debbie Escalante, who has owned the place with James and another brother, Tali, since their dad died, in 2007. “Tali always sang. He wanted to be Sunny Ozuna.”

Little Joe y la Familia is the family’s favorite act now. Joe Hernandez and Villafranca got along much like Willie and John T. Floore. Villafranca put up the money—$125—for Joe’s first recording, with David Coronado and the Latinaires in 1958, and over the years the Westerner remained a regular stop when Joe was traveling around the state. I attended one of his triumphant returns in October. The room was still decorated from an early-summer wedding—most of its business now is quinceañeras and weddings—with Christmas lights wrapped in white chiffon draped from the low ceiling to white posts on the edge of the dance floor. The audience was mostly older folks, all dressed to the nines and all apparently old friends of Little Joe’s, who handed the microphone into the crowd between songs for dedications. He also accepted a number of gifts from people who knew he’d just celebrated his birthday. There was just one strict rule on the dance floor: Even if you weren’t dancing in your partner’s arms, you had to keep moving in a circle. 1005 W. Constitution, 361-575-9109, clubwesterner.com

The Old Coupland Inn and Dancehall

Coupland

Who To See: Kyle Park, John Conlee

Secret Tip: Guests at the inn stand an outside chance of unwinding with the band in the parlor after the show.

Coupland represents the new wave in dance halls, a strange designation for a 105-year-old building. But dancing at the red-brick cavern is a relatively recent phenomenon. Opened as a mercantile in 1904, it knew a brief life in the fifties as La Casa Grande Ballroom. When it was a roller rink in the seventies, some kids probably danced there, and later, when it was a saloon known as Slow Joe’s, barkeepers poured out cornmeal when drinkers wanted a dance. But the floor back then was plywood.

Dancing came in earnest when Tim and Barbara Worthy bought the place, in 1992. They laid an oak wood floor and hung feed sacks from the rafters to help with acoustics and patterned their operation after Austin’s Broken Spoke. Like Spoke owners James and Annetta White, Tim shook hands and Barbara called the shots. If dancers stood still while the band played, she’d walk the floor and twirl a finger over her head like an umpire signaling a home run. The dancing promptly resumed.

But the place has followed a new model since the Worthys sold it two years ago. Austin banker Rick D. Smitherman now runs the hall and adjoining restaurant, living in the five-room hotel upstairs, which was reputedly once a whorehouse. He offers a great deal: For roughly $200, depending on who’s playing, you’ll get a room and dinner for two, a table by the stage, and breakfast in the morning. But thin crowds taught him early what TDHP means by “disappearing dance halls.” Without the plum location of Gruene or the hit-song fame of Luckenbach—halls that make enough money from T-shirt sales to keep their owners flush—Smitherman had to hustle.

So like Schroeder Hall, near Victoria, he embraced the rowdy Texas music scene and its Oklahoma cousin, Red Dirt country. Those acts have an edge to their twang, drawing a younger crowd who packs the dance floor to stand, drink beer, and sing. But even when the Stoney LaRue army commandeers the hall, the back half of the room belongs to dancers. LaRue, for one, sees the distinction. “Sometimes we’ll have kids or granddads in the crowd,” he said before a Coupland show. “When we do, it’s a Texas dance hall.”

The bigger alcohol sales keep Smitherman in business, allowing him to book throwbacks like Moe Bandy and Gene Watson on the weekends in between. All of which has made the hall a budding community hub. “We had a Kyle Park show here on a recent Saturday, and a kid came to the door and asked who was playing,” says Smitherman. “I said, ‘Why did you come if you don’t know who’s playing?’ He said, ‘Well, it’s Saturday, and this is Coupland.’ ” 101 Hoxie (8 miles south of Taylor), 512-856-2226, couplanddancehall.com

Sengelmann Hall

Schulenburg

Who To See: Heybale!, Shiner Hobo Band

Secret Tip: See who’s playing at nearby Swiss Alp Dance Hall and the Moravia Store and do a dance hall crawl.

When Junior Brown played Sengelmann Hall’s grand reopening this June, it occasioned the first proper use of the dance floor since World War II. But after six mournful decades of neglect, the hall now hosts three dances a week, including free polkas on Sundays, and TDHP purists hold it out as a dream example of restoration done right. The new owner, Dana Roy Harper, a 37-year-old Houston artist, held back nothing of his money or time. The new life he gave the hall was a function of family. One of Harper’s great-great-grandfathers was Hugh Roy Cullen, “King of the Wildcatters,” and the portion of the Cullen fortune that made its way to Harper paid for the hall’s million-dollar-plus renewal. That another great-great-grandfather, Gustav Cranz, lived in Schulenburg and was friends with Gustav Sengelmann, the hall’s original owner, provided the inspiration.

Shortly after moving to Schulenburg, in 1877, the brothers Sengelmann, Gustav and Charles, purchased a wood-frame saloon on the site. After it was destroyed in 1893 by a fire that took out much of downtown Schulenburg, then a town of roughly one thousand, the Sengelmanns built its replacement to last and impress. They crafted the walls of brown and yellow bricks, a favored late-nineteenth-century German style, and put cast-iron Corinthian columns inside, with a pressed-tin ceiling over the street-front bar and bead-board panels above the dance floor upstairs. It was home to Charles’ singing society, a Woodmen of the World Lodge, and weekend dances attended by Czech and German families who didn’t want to make the long ride out to their own halls in the country.

Harper bought it in 1998 and started to redo it two years ago. Where possible he stuck with what was there; where he had to replace things he was exacting. He used archival photographs to reproduce the towering front doors and the long saloon bar. He referred to old catalogs for period bar equipment and then had that made. He reclaimed the original piano from a descendant of the Sengelmanns’, then tracked the original benches to a nearby ranch and commissioned replicas. And then he got creative. The new green-velvet curtain behind the bandstand was matched to lederhosen on an oompah band shown in a large portrait hanging upstairs.

He opened a restaurant downstairs that serves family recipes passed down to his Czechoslovakian-born wife, Hana, and prepared by an accomplished, Schulenburg-raised chef, Kenny Kopecky. They rely as much as they can on area farmers for meat and produce and have brought enough dancers to town that three B&B’s have opened in recent months.

“I heard stories growing up from my grandmother about her opa,” says Harper, “so it’s great to see people falling in love with his place again. It’s not a museum devoted to what once was. It is what was.” 531 N. Main (halfway between San Antonio and Houston, 1 mile south of Interstate 10), 979-743-2300, sengelmannhall.com

- More About:

- Music

- Country Music