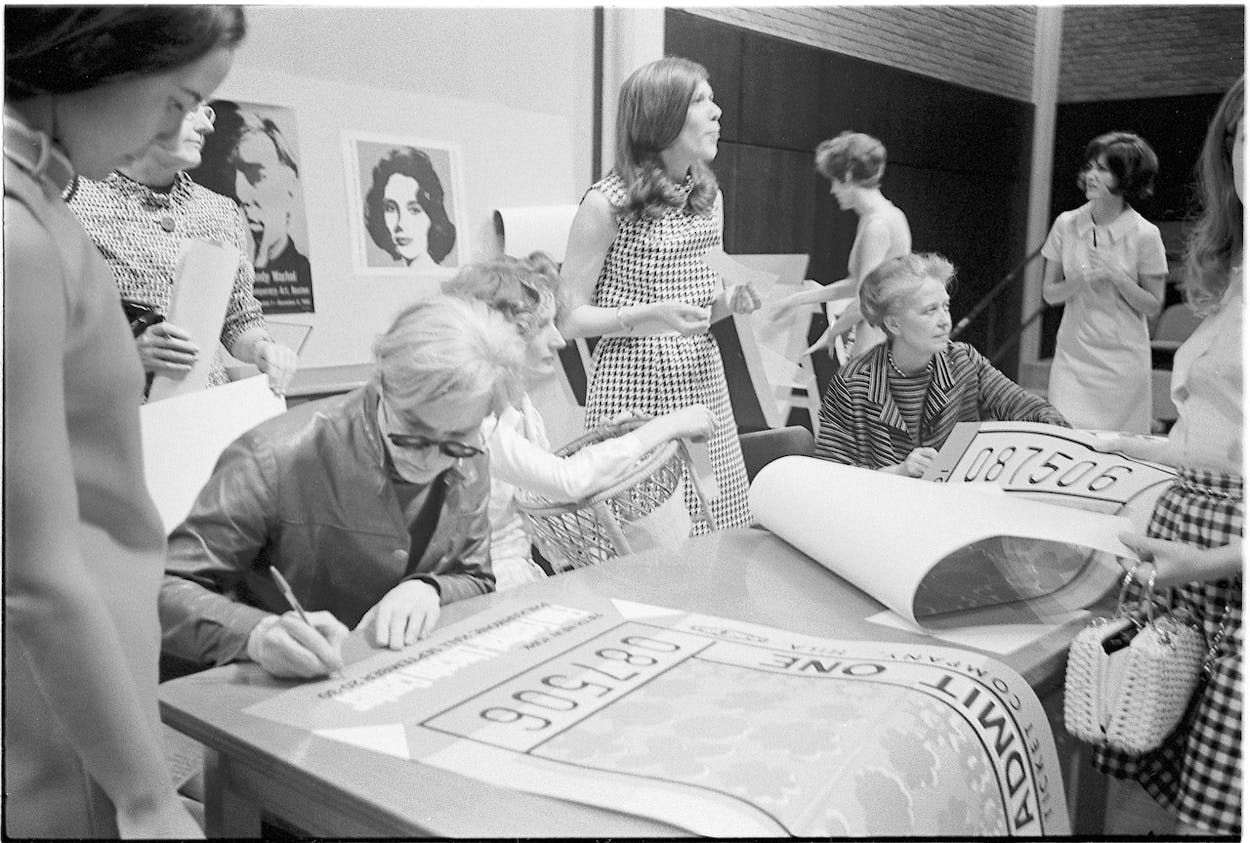

On June 26, 1967, the Houston arts patrons Dominique and John de Menil wrote a letter to the pop artist Andy Warhol. A representative from the Catholic church had asked the couple to curate a pavilion for the Vatican at HemisFair ’68, that year’s World’s Fair, to be held in San Antonio. Dominique refused the offer a few times but finally accepted on the condition that they could have total control over the project.

The de Menils had an existing relationship with Warhol. They were collectors of his work and had recently acquired one of the electric chairs from his Death and Disasters series, which they gave to the Pompidou, in Paris, to inspire political discourse about the death penalty in the United States. The letter to Warhol, written by John, explained the story behind their vision for the HemisFair exhibit.

“’As we were having a drink at our house, I showed [the Catholic church representative] an Italian gothic sculpture and said we would lend objects like that,’” Michelle White, the curator of the Menil Collection, in Houston, read aloud from the de Menils’ letter. “’This prompted him to say that he wasn’t interested in showing religion of four hundred years ago. And no Madonnas, because they antagonize the Baptists. This was an intelligent position, but quite a hurdle for an exhibition, because religious art today just doesn’t exist. It doesn’t exist because what is done is dominated by bigotry. Yet art and religion actually speak the same language where a true artist is involved, regardless of his own religious position. This gave Dominique and me the idea to commission a few of the important artists of today to do, following their own inspiration, pieces appropriate for a church. We think the pavilion should be a church, where various denominations would be in communion.’”

The letter went on but White stopped reading there. She added that the de Menils mention that they were also in discussions with artists Robert Indiana, Jasper Johns, Roy Lichtenstein, Claes Oldenburg, and Robert Rauschenberg. The de Menils’ idea of merging contemporary art and religion mirrored what they were doing with the creation of the Rothko Chapel, the nondenominational sanctum for spiritual contemplation done in collaboration with the painter Mark Rothko, which was commissioned in 1964 and opened in 1971.

The year of the de Menils’ letter, 1967, was around the time when Warhol came out with the iconic banana cover art for the album The Velvet Underground & Nico. He was immersed in filmmaking at the time, a period that lasted during the late sixties and early seventies and yielded around six hundred movies.

Warhol has been quoted as saying, “[My manager] arranged a commission for me from the de Menils to film a sunset for something to do with a bombed church in Texas that they were restoring. I filmed so many sunsets for that project, but I never got one that satisfied me.” Warhol captured the sun on both coasts, in New York, Los Angeles, and San Francisco. But ultimately, the Vatican pavilion never came to fruition because of financial reasons, White said. And save for a series of sunset silkscreens Warhol did in 1972, he abandoned the concept. The handful of movie reels came under the purview of the Andy Warhol Film Project, a partnership begun in 1984 between the Museum of Modern Art and the Whitney Museum of American Art.

In 2000 the AWFP screened a restored version of one of those reels, Sunset, singled out because it had previously appeared in Warhol’s epic Four Stars, a 25-hour movie composed of more than eighty shorter clips, which screened in New York in December 1967. Now Sunset has made its way to the Menil Collection, where on August 19 it began Wednesday through Sunday night screenings that will continue through January 8. That will end up being around a hundred showings, presided over by projectionist Tish Stringer, a film program manager and lecturer at Rice University. “When I first saw Sunset I treated it like a film,” Stringer said. “Then I started viewing it as a painting. And finally it has become more of an experience: a purposeful, relaxing event.”

Sunset is a 33-minute, color-saturated, slow burn of a California sunset, shot on sixteen-millimeter film. Some might suppose that no matter one’s religion, all people are ruled by the sun. “I grew up in Southern California watching the sun set,” White, the Menil curator, said. “That was just something you did. It was almost like a ritualistic, quasi-spiritual sort of experience that I had and a lot of people have had growing up on the Pacific Ocean. For me, it really tapped into that desire and great thrill of watching the sun sink over the ocean.” Guests of the screenings in the Menil gallery space are welcome to lounge on beanbags and zone out.

Accompanying Warhol’s imagery is a poem delivered by Nico, the throaty German singer and actress whom Warhol knew through his involvement with the Velvet Underground. There are moments of silence but Nico’s voice is a constant throughout. She speaks of a black sea and of white skin, often repeating certain lines, as if a mantra.

Next Wednesday, for the Menil’s first installment of the “After Sunset Sessions,” a suite of ongoing complementary programming that will run through mid-December, a DJ will play songs from or inspired by the banana album, recorded in 1966 during Warhol’s Exploding Plastic Inevitable multimedia event tour. There will also be talks on film and art and, on October 26, a guided meditation led by Alejandro Chaoul-Reich, of the Integrative Medicine Program at the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center.

Warhol took his films out of circulation in the early seventies and their mythology has been exaggerated ever since. As Claire Henry, the assistant curator of the Andy Warhol Film Project, put it, “These stories that grew up around the films became the truth of the films.” She cited the misperceived salaciousness of certain works that Warhol labeled as pornographic, like the 1964 film Couch. Henry also mentioned the 1963 film Sleep, which has been hyperbolized as an eight-hour, real-time shot of a man sleeping, but in actuality is a highly constructed and edited five-hour affair.

Facts about Sunset are also up for debate. We know it was filmed in California, but was it in San Francisco or Los Angeles, and where specifically? What was Warhol talking about with regards to the “bombed” church in Texas? Did Nico, who recorded her voice-over later, write her poem expressly for the film? And how did Warhol and the de Menils intend to screen the film at the HemisFair?

“We imagine that Andy conceived of this as something similar to an Exploding Plastic Inevitable performance, where films might have been superimposed upon one another or run at staggered rates on different walls, not unlike the different walls of the Rothko chapel, so that it would have created this immersive, spiritual, transcending environment,” Henry explained.

Though Warhol was a well-known artist, not many are aware that he was also religious. In fact, he was raised on a steady diet of Eastern Catholicism growing up in Pittsburgh. And strains of its influence appear in his work across all mediums, according to Henry. While living in New York, Warhol apparently was a regular at church on Sundays.

“Later in his life, he would volunteer at the church soup kitchen on the Upper East Side rather than celebrating Thanksgiving or other holidays we associate with family gatherings,” Henry said. “And he would be there with the apron on.”

The Menil Collection, August 26 to January 8, 2017, menil.org

Other Events Around Texas

DALLAS

Lo and Behold

The German auteur Werner Herzog is a wizard of topical filmmaking, from his current movie, Lo and Behold: Reveries of the Connected World, about the margins of Internet life, to his 2013 four-part TV series “On Death Row,” featuring prisoners in Texas. So expect him to talk about current events during “An Evening with Werner Herzog,” rife with brain-droppings from a restless mind always on the hunt for quirky new subject matter to add to his oeuvre of more than fifty movies.

Winspear Opera House, August 31, 7:30 p.m., attpac.org

DENTON

No Bull

Cowboy life in certain parts of Texas might be increasingly a thing of the past, as evidenced by the recent purchase of the famed Waggoner Ranch by sports team owner Stan Kroenke. But in other places, like Denton’s North Texas Fair and Rodeo, cowboys will be riding high on the final weekend of the nine-day event, with events such as the Bull Blow Out, as well as the Cowboy Protection Match, in which bull fighters demonstrate the tactics they employ to keep riders safe after they’ve been tossed to the ground.

Miller Lite Rodeo Arena, August 26–27, ntfair.com

HOUSTON

The Stars at Night

During season two of the TV drama “American Crime,” filmed in Austin, Houston’s NobleMotion Dance company gained national attention for an exquisite four-and-a-half-minute uninterrupted shot of a performance displaying the group’s trademark physicality and playfulness with light and dark. For Saturday’s “Supernova” program, NobleMotion will reprise its work “Spitting Ether,” a crowd favorite from its repertoire, plus debut two new ones, including the eponymous piece, which requires the audience to wear sunglasses as the story of the life of a celestial star is told by 28 dancers.

The Hobby Center, August 26 & 27, 7:30 p.m., noblemotiondance.com

STAFFORD

Wacko From Waco

The last time we caught up with Waylon and Willie running buddy Billy Joe Shaver, he had just returned to performing after shooting a man in the face outside a bar in Lorena. Now, on the occasion of a string of Texas dates beginning on Friday at the Redneck Country Club, we acknowledge his most recent return to the stage, this time after a prolonged hospital stay, proving that at 77, he is abiding by his classic song “Live Forever.”

Various locations, August 26 to November 18, billyjoeshaver.com

MONTGOMERY

Just Breathe

Stress is something that we all encounter, and breathing, something that we all do, is a convenient remedy for combatting it. At the Sound Healing Meditation Workshop, let Darrell Hicks, a professional body worker, spiritual teacher, and musician help you channel one natural force to deal with the other, perhaps with the aid of one of Hicks’s instruments of choice: the digeridoo.

Deer Lake Lodge, August 26, 7 p.m., facebook.com/events/1025661337554476/

- More About:

- Montgomery

- Houston

- Denton

- Dallas