The Blanco River winds 87 miles through green hills and dramatic, rocky bluffs. It is dammed in more than ninety places, and a quirk in state law has ceded ownership of most of the riverbed to private landholders. They purchased it, and they pay taxes on it. But the Blanco is still wild. It flouts dominion. The river rises and falls, floods, and is redrawing its boundaries all the time.

Even modest swells can smash wooden decks and level stately trees. A family who enjoys a swimming hole for generations might find it filled with rocks after a single heavy rain. Once, I was walking with a property owner near Wimberley when he realized a gravel bar had hopped from one bank to the other. He seemed indignant: such caprice was an affront to his ownership. People who have known the river a long time are used to these changes, however, and they tend to get less worked up over them.

On a November morning in 2013, I met up with William T. Johnson, an owner of the Halifax Ranch, which lies on the edge of the Hill Country west of Kyle. He was going to search for a couple of kayaks he’d lost in a flash flood on the Blanco ten days earlier. We climbed into his green Land Rover and rumbled down muddy trails beside the still-swollen river, stopping only to open gates at barbed-wire fences and to admire the damage. Flooding from the torrential storm had scoured the deep and narrow canyon walls of a dry tributary called Halifax Creek; the canyon basin seemed to have been struck by a tornado. Mature trees had fallen, shoved into enormous piles. The rock walls were chipped, broken, and deeply gouged. In the raw places where cascading water had knocked off large hunks of rubble, the stone was bright white, sharply contrasted by the weathered gray limestone around it.

“Oh, my God,” Johnson said, looking through his binoculars. “I’m getting glimpses of stuff I’ve never seen. See that exposed rock? I’ve never seen that before.”

Like so many flash floods in the Hill Country, this one had struck almost without warning. On the night before Halloween, the storm’s bull’s-eye had landed above Wimberley, several miles upstream. As 14 inches of rain soaked the hills that flank the southwestern edge of Austin’s sprawl, the runoff surged into the Blanco and hurtled toward Johnson’s ranch, then on to Kyle. Between midnight and 5:30 a.m., the river had risen from 4.3 feet to more than 35.9 feet at the flow gauge maintained by the U.S. Geological Survey in Kyle. The Halloween Flood, as it would come to be known, had been the town’s worst flash flood in more than half a century—a mere 7 inches shy of the deadly Memorial Day Weekend flood two years later.

Sitting next to Johnson in his off-road vehicle, I stared at the destruction to Halifax Creek. “It’s like a landslide,” I said.

“Yeah,” he replied. “Let’s go to the top.”

We left the river valley and drove uphill into rolling land covered in live oak and ashe juniper, commonly called cedar, its sweet, piney aroma filling the air. Wild turkeys gobbled as they darted across the road and disappeared behind stands of prickly pear. The trail ended, and we got out and walked. Johnson pointed to various plants in our path: pencil cactus, or tasajillo, with its bright-red ornamental fruit and vicious spines, and oreja de ratón, or mouse-ear, also known as Southwest bernardia, a densely branched shrub with small, hairy leaves like mouse ears.

Johnson stopped at a wavy patch of waist-high grass and ran his hand over the tops of the stems. “You know your grasses?” he asked. “That’s the sideoats grama, the Texas state grass.” Taking a closer look at the small, golden florets growing down the side of the stem, he grabbed the grass and pulled it from the shallow soil. I was reminded of our state flower, the bluebonnet, and the urban legend that forbids Texans from picking it. “You didn’t just break the law, did you?” I asked.

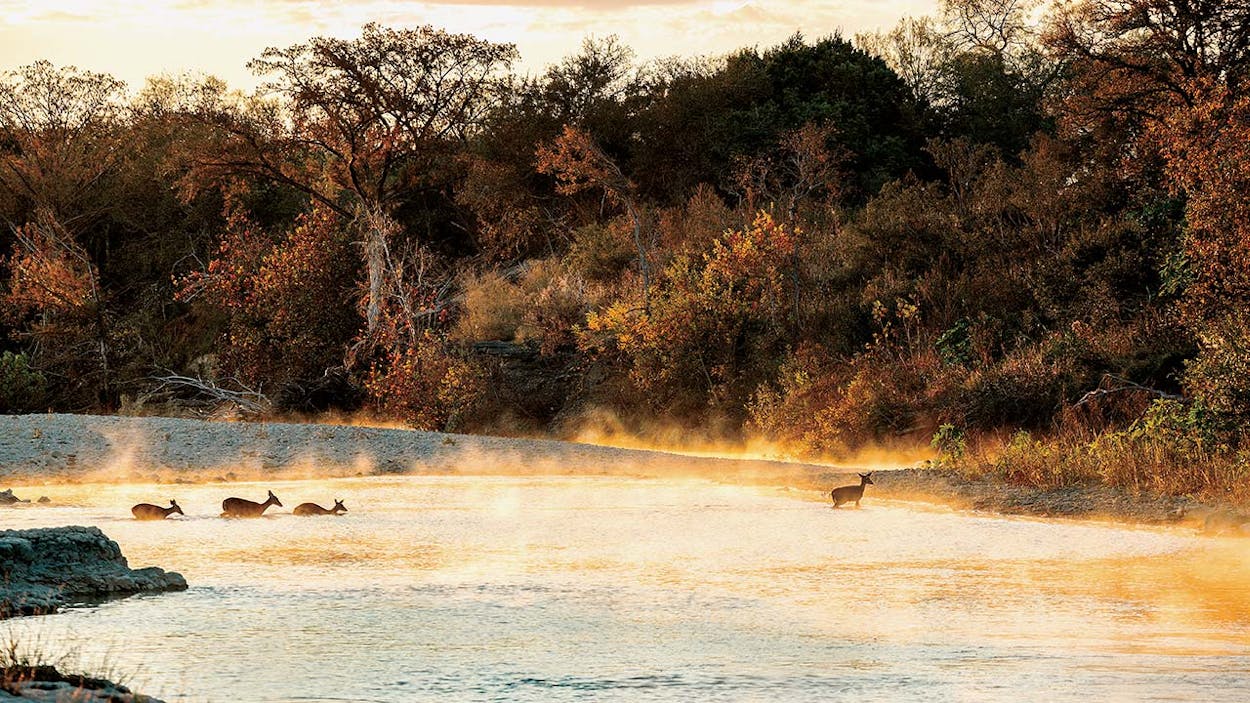

We walked on, kicking our way through the grass. Almost without warning, the land ended at a rocky precipice. “Watch your step,” Johnson said. “It’s quite a drop.” I inched toward the ledge, a balcony framed by pads of prickly pear. Nearly two hundred feet below, the Blanco swept around a sharp bend, a breathtaking swath of blue-green curving through a brown autumn landscape.

The water was deep but astonishingly clear at this spot, which is known as Halifax Hole. Every submerged rock and drop in the limestone riverbed was visible from above. “This is what I call the Great Bend of the Blanco,” Johnson said. “Up until here, it’s been flowing east. Here, it arrives and flows south. It’s a major change of course.”

We were standing near a barbed-wire fence that marks the eastern edge of Halifax Ranch. We could see the river far to the south, its waters still brimming. “Look down there,” Johnson said as he pointed just beyond Halifax Hole. “Usually, if there’s water at all, it’s pretty modest.”

The Blanco, he explained, is actually known to stop flowing downstream from the hole in particularly dry seasons—even as the river continues to run beautifully upstream. In 1912, in fact, the San Antonio Express reported a dramatic disappearance of the Blanco, when the bottom “fell out” of the river as water drained through faults and fractures in the riverbed. “There was a large body of water,” reported the newspaper, “which unaccountably disappeared all at once, and there was not even a wet spot left. The fish were left high and dry, out of their native element—there was nothing to be seen, and all that was to be heard was the sound of rushing waters in ‘the regions below.’ ”

This caused consternation among the people who needed a fully flowing river to power their mills and water their livestock, and so the owner of the Halifax Ranch at the time, a man named Mike Rodgers, hired a one-hundred-man crew to fill a “rent” he identified in the riverbed with rock and seal it with cement. But this ultimately failed to stop nature’s course; Rodgers had overlooked two smaller sinkholes just upstream. So much water drains through them that, during dry times, Halifax Hole is where the Blanco stops flowing aboveground.

And where does it go? The subterranean river percolates through gaps, cracks, caverns, and fissures in the limestone, creating ever-wider passageways through which it moves, unseen, beneath our feet. In 2008 and 2009, to trace the Blanco’s path after it vanishes from sight, hydrogeologists from the Barton Springs Edwards Aquifer Conservation District and other entities set up a research spot at one of the sinkholes, known as Johnson’s Swallet. When they knelt by the surface of the river, they could hear and see the water draining into the ground. To chart its flow, they mixed some fluorescent dye in a plastic ice chest and poured the reddish liquid in the river. Then they monitored nearby wells and springs to locate the dye—which is tasteless, odorless, and invisible to humans once dissipated—where it reemerged from the earth.

Three months later, the researchers made a remarkable discovery. Their monitoring stations detected the dye more than twenty miles to the north, in Austin. It had seeped into one of Texas’s most popular and revered artesian swimming holes, Barton Springs. In wet years, water from the Blanco is not thought to reach Barton Springs at all; the springs’ primary source is drainage from six nearby creeks. But those creeks go dry sometimes, and during periods of drought, it turns out, the Blanco River is the single most important source for Austin’s favorite swimming pool. The Blanco runs dry, but it keeps Barton Springs flowing.

Johnson stood on the bluff at the eastern edge of his ranch and pointed out another spot on the river even farther downstream. “That’s beyond our property,” he said. “It’s what my father called the Nance Mill Hole.” Johnson’s neighbor, Scott Nance, refers to the same spot the Packery Hole. During the Civil War, Nance’s ancestors ran a meatpacking operation at the site. “It’s funny,” Johnson said. “I have names for places, and he has different names for places.”

There is also little agreement on the name of the ledge where Johnson and I were standing as we admired the view. “This is a buzzard roost, though they mostly hang out in the cypress trees or up on top of the bluff here,” he said. “I’ve talked to kayakers who come by and they say, ‘Oh yeah, Buzzards Bluff!’ That’s what they call it. I call it Decker Bluff, because it used to be the Decker Ranch. Old Judge Decker used to be the county judge.”

Johnson’s mother and father purchased the Halifax in 1933, and the Johnsons have added to it over the years. They now own more than two miles of Blanco River frontage. In this section of the Blanco, there are no human-made dams to impede the water’s flow, and canyon walls rise up to two hundred feet above the banks. There are also very few homes. Dave Ellzey, the author of a series of guidebooks on Hill Country rivers, told me he considers the Blanco along the Halifax to be the second-most-remote stretch of river in the Hill Country, after the isolated Devils River (which many would argue is too far west to be in the Hill Country anyway).

Johnson and I drove back down to the river bottom and headed west to Halifax Falls, a series of three steps where the Blanco drops about eight feet. The crash of water echoed across the canyons. In his Blanco River Pocket Guide, Ellzey identifies this landmark as Triple Falls. “He came up with his own name for our waterfall,” Johnson recalled. “I said, ‘That’s not the name of it. It’s an interesting name, but that’s not the name of it.’ ” The talk of names, their origins and conflicts, reminded me of the European explorers who identified so many of Texas’s natural landmarks. Three centuries after Spaniards first encountered the Blanco and named it San Rafael Creek—it earned its identity as the white river after several decades of exploration—we were still debating place names along the waterway.

About a quarter mile upstream from Halifax Falls was a long gravel island whose contours had been molded by wind and water into dunes of red, white, and blue river stone. I’d later end up camping for a night on this island, the Blanco lapping the banks as a silvery half moon hung in the blue sky, and it would seem as if I was in the middle of nowhere—not 4.8 miles from my house in Kyle. Though some maps label it Paradise Island, it turns out that the Johnson family has never seen fit to give the stretch a name. The designations people bestow to various landmarks on his property mostly amuse Johnson, who has searched old county records in an effort to trace the origins of the Halifax moniker that’s been applied to most of the features on his ranch.

“You’ve got Halifax Creek, Halifax Hole, Halifax Ranch, and various other references to Halifax—Halifax Cave, Halifax Falls—and we still don’t really know where it came from,” he said. “The first written reference I’ve found, looking at old deeds and so forth, was in 1857. It referred to the Halifax Cedar Brake something like ten miles north of San Marcos on the Río Blanco.” He paused. “Well, that’s here.” Most of the area’s first settlers came from the southern United States. The Halifax might have been settled by people from one of the Halifax counties in North Carolina or Virginia, or the town in the West Yorkshire region of England. Probably no one will ever know.

As Johnson and I continued our search for the kayaks, the Land Rover’s tires crunching over more downed limbs, he kept an equanimous outlook on the sudden landscape changes wrought by the storm. “That’s just the reality of living on the river,” he said, “and I was starting to think it wasn’t going to happen again. I was kind of shocked that it did.”

At the base of Decker Bluff, or Buzzards Bluff, the narrow floodplain is rich with black alluvial loam that nourishes a forest of tall trees, including a state-champion box elder maple. We were driving along and admiring the view when we came to an unexpected dead end. One of the largest pecan trees I have ever seen had been torn out of the soft soil and now lay across our path.

“Oh, no! Oh, the big pecan!” he said. “And we already lost the other one, hit by lightning three times. This was our biggest remaining pecan. That’s a blow there.” He walked around to the snarled root ball suspended above the gaping hole in the fresh earth. “This I’m really sad to see,” he said. “That was a healthy tree.”

We never found the kayaks. After our tour, I concocted a variety of schemes to revisit the Halifax, and Johnson humored me, seeming to enjoy himself as we explored sites he has known since childhood. Johnson is sixtyish and tall, with fine breeze-blown hair, and he almost always wore the same pair of mustard-colored pants on our adventures. When he is not tending to his land along the Blanco, he runs an organization called the Burdine Johnson Foundation, which is named for his mother and supports the arts, historical projects, education, and other causes. (The foundation provided funding for my book.) Johnson’s interests in natural science have dovetailed nicely with his stewardship of the ranch. Over the years he has opened the Halifax to biologists, hydrogeologists, and other scientists who treat the land as their two-thousand-acre research field.

Johnson and I spent hours during winter, spring, and summer rolling along hard-packed ranch trails, wading or paddling through the river, and climbing up and down brushy canyon walls. Tromping through vines and poison ivy, we traced the tinkling paths of spring-fed creeks to the headwaters, where they issue from cavities in the hillside. There we lifted rocks from the cool, clear shallows to spy on Blanco River springs salamanders, which can survive only in such microenvironments.

One day, to cross the river, we loaded into the Land Rover and drove along the north bank, tracing the ruts left by a frontier-era mail route, then turned and forded the Blanco at the base of Halifax Falls. It was the same crossing once used by pioneers driving horse-drawn wagons to and from the Wimberley village, thirteen miles upstream. Long before the arrival of Anglo settlers, around 1850, native people also used the Blanco River Valley as a natural passage from the hills and plateaus of the west and onto the Gulf plains of the south and east. The Comanche war chief Buffalo Hump likely crossed Halifax Falls before and after his unprecedented attack on the Republic of Texas, in 1840. As Johnson and I crossed the shallows, the truck tires sprayed water in all directions, and I imagined a thousand Indian warriors and their wives on horseback, trotting by the same waterfall.

We headed to the top of the bluff on the river’s south bank, parked the Land Rover, then clambered back down in search of a dark cave where colonies of Mexican free-tailed bats make their summer home. When we found the entrance, I stooped down and reluctantly peered inside. Once, Johnson had told me, he and a party of cavers were about to enter when a feral Angora ram had exploded through the hole and gone tearing down the slope. Hearing nothing this time, Johnson and I crept onto our hands and knees and crawled inside.

This wasn’t exactly bravery—humans have known about the cave for at least 150 years. During the latter part of the Civil War, it and others throughout the Hill Country were mined for bat guano. The Confederate army had run short of munitions, and the high nitrate content of guano provided a key ingredient in the production of gunpowder. Along with sulfur, the third ingredient was charcoal, which was produced by burning the cedar trees that grew in brakes along the Blanco.

John Thomas W. Townsend, a Confederate veteran from Wimberley, hired Mexican laborers to locate the caves and haul away the bat droppings. They filled buckets and used a pulley and rope to lower them to the river far below, where the excrement was loaded into carts and pulled by mules to manufacturing facilities, including one in Bastrop. Searching the cave many decades after the Civil War, Johnson’s father found hand-hewn timbers inside. In fact, directly above the cave still stand two wooden poles that might have been used to mount the pulley system.

Not everyone contributed to the war effort, however. Even as workers were excavating guano at the bat cave, conscientious objectors who wanted nothing to do with the South’s fight were waiting out the war a mile downstream in Halifax Canyon. “One of these evaders prophesied that the war would last for years; so he acquired some maple trees, no one knew where from, and set them out in the valley near his hide-out,” writes Tula Townsend Wyatt in the 1963 history book Wimberley’s Legacy. “His plan was to have his own sugar supply and after the war he would make furniture from the wood. A few of the trees were still growing in the canyon in the early part of 1900.”

The author goes on to scold the nameless men who hid at Halifax Canyon and Little Arkansas, another picturesque canyon whittled into the hills about five miles upriver, for shirking their duty in the Civil War. “Perhaps they had not a pang of remorse for not having served their country in the time of need; but on the other hand, there may have been moments of hopeless anguish caused by a sense of guilt that followed them throughout life.”

Early one morning in late spring, when delicate yellow flowers dotted the grassy clearings amid the cedar and oak, Johnson and I tagged along with a wildlife biologist and self-described “bird nerd” named Mark Gray who was conducting a seasonal bird survey on the Halifax. The survey informs the Johnson family’s efforts to manage wildlife on the ranch.

We hit the trail before dawn, climbing out of the Land Rover at chosen spots to watch and listen. Mostly listen. Gray estimated 98 percent of surveys are done by sound. He would hear a chirp, song, or squawk; nod his head as if to say, “Got it!”; and jot the species name into a database on a tablet computer. He heard the peter-peter whistle of black-crested titmice and the harsh trills of great crested flycatchers, and the ever-present canyon towhee, which ricocheted like a Gatling gun—pew-pew-pew! “That very sweet-sounding one is the painted bunting,” said Johnson, who is also a birder.

Johnson and Gray had selected survey spots in transitional areas between ecosystems, where the upland forest gives way to canyon, for example, or at the edge of a clearing in a juniper forest. We heard white-eyed vireos and northern parulas. Gray was thrilled to spot a sandpiper flying across the water but was frustrated when a “stupid mockingbird” crowded out the other songs of the forest.

I could not remember the last time I’d lingered quietly in a forest and listened to birdsong. As I stood, distracted only by a few cactus spines in my sock, the birds’ music lulled me into a trance that did not end until the biologist pointed out some dark-winged scavengers swirling the sky above the Blanco. “Black vultures will kill a calf,” Johnson said.

Many mornings later, Johnson and I were joined by an experienced and enthusiastic botanist named Bill Carr. We tramped past the felled pecan tree next to the river, in the deep shade of Decker Bluff. Carr knew every plant in sight. He sampled the edible ones, including wild lettuces and the waxy red flowers of Turk’s caps. As we looked up the sheer face of the canyon wall, Carr explained how the canyon and river create one of the more fascinating environments for plants in Central Texas.

“All of this is Cretaceous limestone,” he said, running his hand across the white-gray wall of rock. Water from the aquifer travels through it, he explained, and drips out of numerous small holes that we could see in various stacks of limestone. “The water down in these canyons is not really related to the river, but it keeps it all nice and moist, so you get these great big deciduous trees, a whole bunch of rare plants that kind of hang out in these refuges down in the bottoms, plants that can’t grow on the tops where it’s hot and dry and windy. These are great shelters for them.” Some of those little holes were occupied, however.

“For me the cool thing about the Edwards Plateau is there’s seventy-five plant species that don’t grow anywhere else in the world,” he continued. “Some of them are really rare, but most of them are really common, and here’s one right here.” Carr pointed to a spot about a quarter of the way up the canyon face. “This thing with the white spikes? It’s called a butterfly bush. See how it’s just growing right out of the rock? That’s the only place you ever see it, growing right out of a little pore in solid limestone.” Other butterfly bushes had sprouted from holes in a single band of limestone. “There’s little water channels back in there, and these things could have roots going back ten feet, probably,” Carr said.

“I was wondering how the plant would get a toehold,” I said.

“And how it gets seeds in there is just a mystery to me,” he replied.

The side of a cliff might be an inhospitable place to make a home, but it has its benefits, Carr said, explaining that eating habits of herbivores, like white-tailed deer, shape much of the vegetation on the plateau. He also pointed out a leafy plant that had wound itself around a tree. The plant was called a cow-itch vine.

“Why do you call it a cow-itch?” I asked.

“I have no idea,” Carr said. “If only the cows could talk.”

Johnson pointed out a smaller green plant on the forest floor. “This almost looks like wild tobacco,” he said. “What would you say it is?”

“It is wild tobacco, and I have a theory on this,” Carr said. “We always find it around places where Indians would have camped in a rock shelter near perennial water. You hardly see it anywhere else. I bet they were carrying this around, smoking it, and that’s how the seeds got dispersed. It’s a tobacco plant. It’s not the one we smoke, but I’m sure they did, because it’s here.”

“So we could smoke it?” I asked.

“We could. You bring any papers?”

I had not.

Growing alongside the Blanco and other canyon-hemmed streams are plants found nowhere else on the Edwards Plateau. Some of them, in fact, are more typically observed in places like Tennessee. Their range leaps hundreds of miles only to show up in shady spots in Central Texas river canyons.

“Like, if we see some columbine,” Carr said. “Those things don’t grow in East Texas even. They skip that whole area. The theory is that when the climate was more conducive to their growth, all over North America these things were more widespread than they are now, and they’ve persisted here as it’s gotten hotter and drier. These cool, moist places are the last places they hang out.” In other words, these plants are remnants from the most recent ice age. In addition to eastern columbine, bigfoot morning glory and Carolina basswood are plants that are common elsewhere but hardly found in Central Texas. So is the elderberry, for that matter. Carr spotted the bush right off.

“This is the one they make elderberry wine out of,” he said. “I wonder what it tastes like.” Carr popped a berry in his mouth and made a sour face. “I guess they’re better as wine.” Johnson and I also tried one of the berries, which grow in clumps but resemble smaller, darker blueberries. “Well, if we’re going to die, we’ll all die together,” Carr said. “They’re sort of insipid.”

As we explored, we also saw hellfetter, “the greenbrier from hell”; wisps of Spanish moss; chatterbox orchids; clammyweed—“and if you touch the fruit, you figure out why it’s called clammy, because it’s real sticky, glutinous, and beautiful”—and the ubiquitous gravel-bar brickellbush, the first plant to emerge on the banks after a scouring flood.

Some of the plants struck me as notable for no other reason than their scarcity. Roemer’s false indigo, with twiggy branches and deciduous leaves, is the kind of bush you might step on and never give a second thought. It is found nowhere else in the world but in the partially shaded limestone soils of the Edwards Plateau and Coahuila, Mexico. Around the time Texas was being annexed by the U.S., the German naturalist Ferdinand von Roemer, the “father of Texas geology,” was busy researching the plants and landscape of the new state. He took several plant specimens, including Roemer’s false indigo, back to Germany, where they were catalogued and described. Over the decades, the false indigo specimen was lost or destroyed. In 2012 botanists were able to replace the missing specimen with one they found on Halifax Ranch.

Another rare plant that Carr pointed out was the canyon mock-orange. There are fewer than thirty known occurrences of this small shrub in the entire world, and it is highly vulnerable to extinction. But Carr found it growing from rocky cliffs, with gracefully drooping branches and delicate leaves. When the mock-orange blooms in the spring, it produces cumin-scented white flowers. The plants are so rare and in such out-of-the-way locales that almost no one will be there to smell them when they bloom.

In addition to botanists, birders, and hydrogeologists, there have also been writers and poets who have found inspiration at Halifax Ranch. When authors come from around the country to give readings at the Katherine Anne Porter Literary Center, in Kyle, they are treated to a tour of the ranch. In a 2000 essay, the writer Annie Proulx describes her own visit to the Halifax, “edged by the beautiful but drought-stricken Blanco River.

“A rare caracara flew above the trees at the edge of the river,” Proulx continues. “Whitetail deer burst from every thicket. Our guide pointed out a barely visible horse-crippler cactus with curved thorns like a sail maker’s needle. On the way out our host stepped on the brakes rather than run over a tarantula. We all got out and looked at it. It stood still, waiting for whatever was going to happen. It seemed handsome and young, about two and a half inches tall. A tickle with a long stem of grass sent it galloping into the brush.”

I can picture Johnson mashing the brakes of his Land Rover to yield to the tarantula. About a decade ago, his family decided to protect most of the Halifax from future development by placing it under a conservation easement. In exchange for promising not to develop their land, Johnson family members receive tax benefits and will be able to enjoy their private wilderness in perpetuity.

Smaller patches along the Blanco are also being protected via similar easements, and conservationists hope to lock up as much of the riverfront as they can before the Austin-to-San Antonio sprawl overruns the Blanco entirely. Of course, time is running out. In recent decades, miles of riverfront have been transformed into suburban neighborhoods, and more subdivisions are in the works, with one real estate salesman describing the market for river frontage as a “Roman orgy on steroids.”

It all reminds me of the words of John Graves, whose canoe trip down the Brazos River more than half a century ago paid homage to another changing waterway. Writing about ongoing efforts to reshape Texas rivers, he declared, “We river-minded ones can’t say much against them—nor, probably, should we want to.” Even so, I am glad to know the Halifax will be spared such progress, a remnant of the Texas wild. And I hope someone is enjoying those two kayaks.

Copyright © 2017 by Wes Ferguson and Jacob Croft Botter. From the forthcoming book The Blanco River, by Wes Ferguson, to be published by Texas A&M University Press in February 2017. Printed by permission.