HE CAN’T, TO SAVE HIS life, remember the words to the poem.

“God, I used to know this. Obviously, ‘I am Joaquin,'” begins Joaquin, his untidy right eyebrow perpetually arched; dark, elongated eyes scanning nothingness for a clue. It is a sunny San Antonio day, a good day, I decide, for reciting poetry over breakfast and a linoleum table at Jim’s Restaurant in the northwest part of town. But Joaquin is stuck, utterly so. “I used to know the first four lines!” Pause. “‘Lost in a world of confusion,’ something, something . . .”

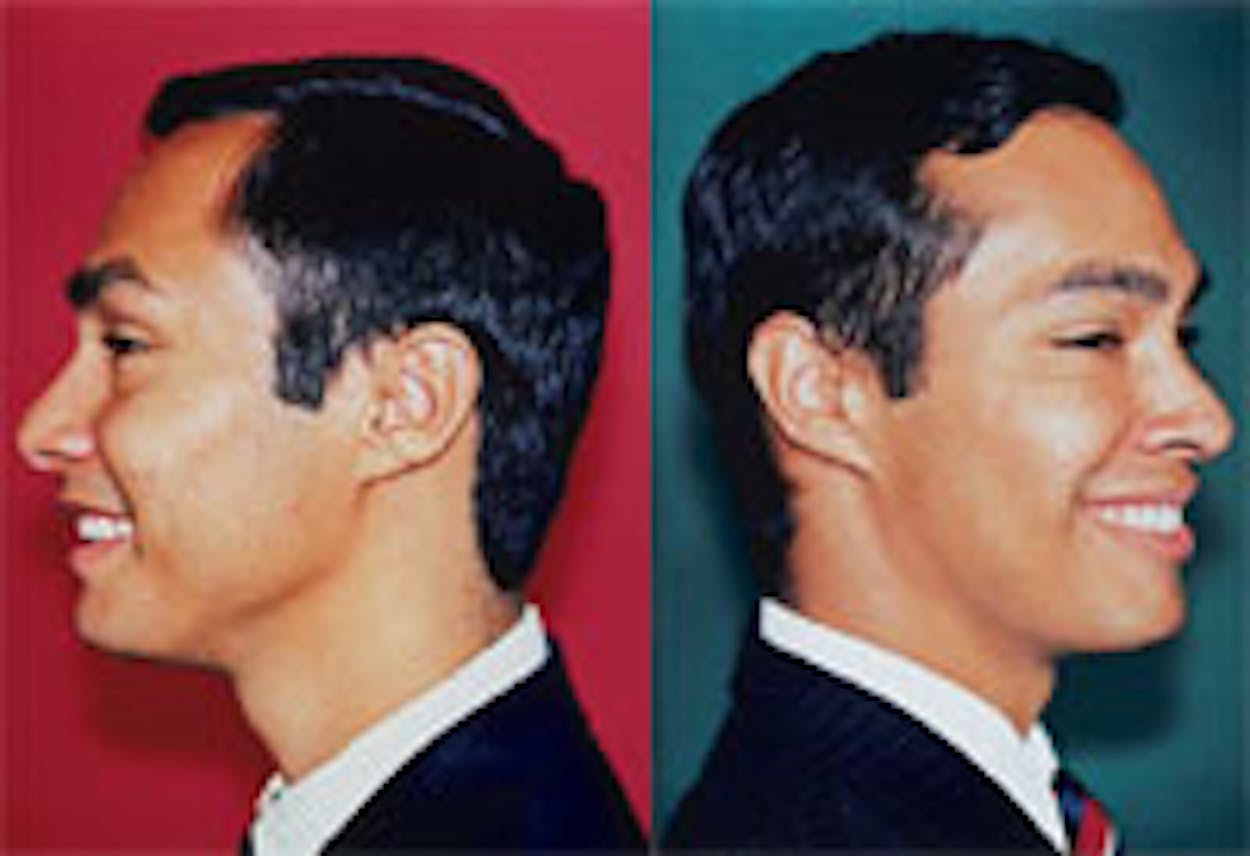

“God!” he laments finally, flashing his Joaquin Castro smile now—a wide, infectious one that starts at the corners of his mouth and bursts into fullness without warning. “Now you’re gonna write that I don’t know ‘I Am Joaquin.'”

The 1967 Chicano movement poem by Rodolfo “Corky” Gonzales, a standard Chicano Studies 101 reading assignment—which, I’ll grant, I can recite only after looking it up on the Internet, but it has been seven years since I took the class—begins like this:

I am Joaquin,

lost in a world of confusion,

caught up in a whirl of a

gringo society,

confused by the rules,

scorned by attitudes,

suppressed by manipulation,

and destroyed by modern society.

My fathers

have lost the economic battle

and won

the struggle of cultural survival.

And now!

I must choose

between

the paradox of

victory of the spirit,

despite physical hunger,

or

to exist in the grasp

of American social neurosis,

sterilization of the soul

and a full stomach.

It seems ironic—at least melodramatic—to have Joaquin Castro recite this poem today, which is really the reason I pressure him into doing it. Truth is, I want to witness the incongruity of this prim, fashionable, smooth-talking, middle-class Mexican American fretting over cultural assimilation and grieving his alienation from gringo society. The guy graduated from Stanford and Harvard. He’s vying for a seat in the Texas Legislature. He had, until the sobering tediousness of corporate legal work hit him like a brick, an extremely lucrative job, one that he’s replaced by opening up his own legal practice with a high school friend and his brother, Julián—a rising politician himself, who sits on the San Antonio City Council. At the surface, the intersection of Joaquin trying to recite the story of his tormented namesake seems out of place, the perfect anachronism. And so I watch delightedly.

But as odd as it appears, it also makes perfect sense, and this too I know: Joaquin’s mother, Rosie Castro, was the chair of the Bexar County Raza Unida party and helping out with a Diez y Seis de Septiembre menudo cookoff in 1974 when the labor pains struck and she ended up at the hospital delivering two teeny, premature, identical baby boys. The first twin got named by his father, the cookoff conspirator and a fellow Chicano activist: Julián it would be. And the one who popped out one minute later Rosie christened Joaquin, after the epic poem.

Those were the days, days Rosie Castro remembers well, when San Antonio’s Mexican Americans—which is to say the city’s ethnic majority—had little if any access to power because the place was run by an Anglo business establishment that handpicked the city’s leaders, mayor included. They were taxed, yes, but the services their money paid for always seemed to end up on the fast-growing north side of town, not the west or the south, where the Mexican Americans lived, not the east, where blacks have traditionally made their homes. Inspired by the ideology of the national civil rights and anti-war movements of the sixties, as well as by the work of La Raza Unida, a flourishing but ultimately short-lived third-party movement, Rosie and her kind wanted neighborhoods to have a direct voice in matters that affected them. “Barrio representation” they called it.

And so they mobilized, organized rallies, registered voters, and ran for office—sometimes in droves, just to make a statement. A firebrand who could step up to the podium and incite a crowd “in real hell-raiser fashion,” as one contemporary described her, 23-year-old Rosie herself ran for the city council in 1971 on a slate called the Committee for Barrio Betterment. She finished second among four candidates in the primary for Place 3. None of the slate’s candidates won, yet their election results helped lawyers with the Mexican American Legal Defense and Educational Fund (MALDEF) convince the U.S. Justice Department that, if San Antonio council members were elected from individual districts instead of citywide, Mexican Americans in San Antonio would have chosen some of their own.

Two life-altering things happened because of Rosie Castro’s engagements in those heady days. First, she had the twins, on Mexican Independence Day. Then, facing federal pressure in 1977, San Antonio voted to shift from electing council members at-large to a single-member system, forever changing the racial makeup of municipal leadership and making it possible for a future generation to achieve what she had not.

Rosie had uttered some prophetic words when she lost the election in 1971: “We’ll be back,” she told the San Antonio Light. And exactly thirty years later, she was. In 2001, just one year out of law school (on Cinco de Mayo, mind you), 26-year-old Julián Castro became the youngest city councilman in San Antonio history, soundly defeating five challengers with 59 percent of the vote. Friends and family had watched Julián’s political ambitions blossom in college and felt certain that he would run, especially after he began raising seed money among law school friends at Harvard. It was destined to be, one could almost say, considering that Rosie had raised her two boys in the world of politics and activism and had showed them, over and over, the importance of serving their community. “When Julián was installed, it was just such an incredible thing to be there because for years we had been struggling to be there,” Rosie says. “There was so much hurt associated with being on the outside. And I don’t mean personal hurt, but a whole group of people had been on the outside—the educational, social, political, economic outside.”

But that summer, surprising those who saw Joaquin as the less politically inclined one—the one who would carve out his own professional path, in business, perhaps—the younger twin quit his job at Akin, Gump, Strauss, Hauer, and Feld, where Julián also worked, and announced that he too was running for office. He outpolled the District 125 incumbent legislator, Art Reyna, in the March Democratic primary, taking 64 percent of the vote. Next month he goes up against Republican Nelson Balido, who is 32, the president of a technology consulting firm, and the son of Cuban immigrants.

Physically, it is impossible for anyone but those closest to them to tell them apart. But in personality, the Castro brothers are significantly different. The older of the twins is respectful, pensive, soft-spoken, a homebody who likes to write and has meticulously studied the path of policymakers he admires—among them John F. Kennedy, Henry Cisneros, Bill Clinton—so that he might chart his own political journey, one he hopes will take him up the ranks of municipal government to the Texas governor’s office, possibly beyond. “He’s just an honest person,” says Rosie about Julián. “He’s like a good friend to have, which is one of the things I miss now that he’s busy on the council.” The other one is witty, energetic, fun, a world-class socializer who likes public oratory and is more interested in testing the waters politically than in setting his future in stone, curious to find out how he would be received as an elected official but hoping, along the way, to do something to change radically San Antonio’s rather dismal education record. “He’s a real joyful ‘people’ kind of person,” Rosie says of Joaquin. “He’s the kind of person that all of a sudden will throw his arm around you.” Together they represent Rosie’s second chance—two of them, actually—to finally enter what she calls the Inside, to sit at the table where policy gets made “instead of just having to pound on the damn door to have someone hear you.” The twins bring together her two lives: her fight for the people and her role as a mother. Tearing up—a highly unusual event for the thick-skinned 55-year-old woman who sometimes swears like a sailor and mostly raised her boys as a single mom—she recalls how a friend once pointed out that, ultimately, “my greatest contribution to the community may be them.”

And yet, her sons are doing politics in a different era. Julián and Joaquin Castro belong to a generation, our generation, that calls itself Hispanic or Latino, that learned about civil rights struggles in the past tense, that is having to draw the political agenda at a time when group rights have become increasingly unpopular. If the Castro story reflects the journey of Texas Mexican Americans from the political outside to its center, it also reveals an inside fraught with complications for people like them. Among many others, the twins’ challenges will be to overcome the label of “ethnic politician” at the same time that they embrace their ethnicity, to define what it means to “serve the people” in a world of free-market economic development and centrist politics. Granted, they come to the task with the kind of training their mother and her generation could only have dreamed of. But the question is worth asking: Will Rosie Castro win this time around?

WHEN I WAS A STUDENT AT Stanford University in the early nineties, I thought of Joaquin and Julián Castro as two preppy, courteous, interchangeable San Antonio brothers I had been introduced to because of the Texas roots we shared but whom I seldom saw. Every now and then one of them—I never knew which—would show up alone at one of our parties at Casa Zapata, the university’s Chicano-themed dorm. He would watch silently from the room’s shadowy corners or balance himself on the armrest of a couch while the rest of us grooved to hip-hop, swayed to Chicano oldies, and hopped to the thumping, jumping rhythm of West Coast Mexican banda music in a carpeted dorm lounge. We brought on Christmas with a posada, with rackety ballet folklóricos and mariachis. We were members of Movimiento Estudiantil Chicano de Aztlán (“MEChA” for short), tutored barrio kids, tried to get grapes eliminated from the university’s dorm menus, designed a Chicano studies major, taught the university’s Latino cooks and janitors to speak English, and printed our own publications, Aztec symbols dancing across the top. We fought the good fight. We were Chicanos.

That was not Julián and Joaquin’s scene. Though I mistook them for those private-school kids who came to Stanford from San Antonio, the truth was that while the rest of us reveled in our newfound ethnic identity and social consciousness, the Castro twins had already completed their political initiation at home, years before. Their father, schoolteacher Jesse Guzman, had once served as the director of Colegio Jacinto Treviño, founded in the height of the movement for and by Chicanos. Raising twins was a project, especially since their parents were more concerned with changing the world than with making money. When the boys were seven, Rosie and Jesse, who had never married, split up, and Rosie had to stretch her salary as an employee in the city’s personnel department among two growing boys, her aging mother, and herself.

But as she did with politics, she had a handful of core principles she applied to child rearing. No guns was one. (“I was trying to get ‘no loud musical instruments,'” she recalls wistfully.) No matching clothes for birthday presents, please. And especially, no dream quashing. Her philosophy went like this: “If you really want to teach someone that they can be whatever they want to be, you don’t start by telling people what they can’t be.” And so, whatever the idea was that week—”whether it was boxer or police officer”—she worked her social and political networks and introduced her boys to people whose careers they thought they might want for themselves.

By junior high Julián and Joaquin Castro were confident and ambitious and notoriously competitive teens, which drove their mother crazy. (“I was, like, ‘Have fun! Not everything has to be competitive!'”) They monitored each other’s grades viciously. Once, the story goes, their tennis coach had to stop their doubles match because the twins wouldn’t quit screaming at each other. At Jefferson High Julián graduated ninth in his class and Joaquin twenty-seventh. They had applied to a smattering of in- and out-of-state universities, but when Stanford said it would take them both, their choice was made. “I guess staying together didn’t require any special effort or thought,” says Joaquin. “I remember noticing when I went to college, I would refer to things in the collective—’Our mom,’ ‘Our dad.’ It probably took about a year or two to drop that and speak in singular form. In fact, I probably didn’t have a best friend at Stanford because I was always hanging out with my brother.”

In almost every way, the San Francisco Bay Area was a different world from South Texas. It was green, ethnically diverse, politically progressive. It was also a place where, curiously, families and groups seemed largely absent from the public scene. At the frenetic San Francisco airport, Joaquin noticed, “it was always individuals taking the SuperShuttle or a cab or bus home.” But stepping out of the familiar changed their perspective forever, the Castro brothers now say. The experience made them highly reflective—about themselves, about San Antonio, about how the two might come together someday.

During his freshman year, Julián wrote an essay in which he described his gradually awakening social consciousness. Titled “Politics . . . maybe,” it was a response to his writing instructor’s question: Do people ever make assumptions about what you’ll do after college? How do you feel when they do? The eighteen-year-old responded: “How many of these ‘functions’ have I been to in my lifetime? They all seem the same to me now—the same speeches and speakers, the same cheese and ham sandwiches, the same people, ones whom I see only at these political gatherings, ‘functions’ my mother calls them, and, of course, the same expectations of me. ‘So, what are you going to do after you finish school?’ my mother’s friend asks me. ‘Uhh…’ Can he see my eyes float along the carpet?” After describing his initial resistance to his mother’s hectic and seemingly rewardless political world, Julián reflected on the effects of her work. “Maria del Rosario Castro has never held a political office,” he wrote. “However, today, years later, I read the newspapers, and I see that more Valdezes are sitting on school boards, that a greater number of Garcias are now doctors, lawyers, engineers and, of course, teachers.” By the end of the essay, the child replies to his mother’s friend’s question: “Maybe politics.” So impressed was Julián’s professor that she had the essay published in a writing textbook called Writing for Change, where it was placed just before Martin Luther King, Jr.’s “Letter From Birmingham Jail.”

She wasn’t the only professor who took notice of the Castros’ political potential. In their sophomore year the twins took a lecture course on urban politics with Luis Fraga, a Corpus Christi native. As the university’s sole Mexican American political scientist, Fraga has mentored many of Stanford’s Chicano students with political aspirations. In the twins he noted a far greater level of political sophistication. Other students who aspired to work in public service were debating whether to pursue politics at home or elsewhere, but with Julián and Joaquin, Fraga says, “there was a clear commitment to the home community and a very clear understanding of the work involved and the strategic decision making that had to occur. It makes you believe,” he says, still amazed eight years later, “that some people are just political animals.”

They tested the waters by running for student senate and picked up the same number of votes, more than anyone else on the ballot. By the time they enrolled at Harvard Law School, in 1997 (Julián turned down Yale to stick with his brother), they were ready to launch Julián’s 2001 campaign for city council. The elder twin’s commitment to politics was firmly evident by then, written, quite literally, on the wall. In his Cambridge dorm room, two thousand miles from San Antonio, hung a map of council district 7—the West Side neighborhood he called home but also the place that was soon to become his battleground.

IT’S ONLY EVERY TEN to fifteen years that San Antonio wholly convulses over some city matter, but when it does, the scene resembles something like a pep rally gone berserk or the meeting point for a parade at that chaotic moment just before the procession falls into order and marches out like it was never confused at all. The evening of April 4 was one of those rare occasions. At a meeting in the city council’s chambers, the council would decide whether to create a special taxing district northwest of San Antonio for a luxurious golf resort and development known as a PGA Village.

Julián Castro studied the crowd curiously. The rest of his colleagues were only beginning to shuffle over to their seats, but he had already taken his place and was sitting on the edge of his chair, arms crossed on the table, back perfectly straight and head forward, like a good boy posing for his elementary school picture. He scanned the bodies that had filled the room: Elderly men and women in flashy hats, sporting yellow tags that screamed indignantly, “PGA No!” Nicely manicured men and women in business suits, flashing round white stickers that retorted, “PGA Yes!” His eyes ran up the sides of the high-ceilinged nineteenth-century chamber to the balcony, where activists stood in green vests, holding neon-pink protest signs. The guttural sounds of Native American drums and the rhythmic chanting of youth activists wafted in from outside.

Even as the pre-meeting chaos grew louder, Julián seemed to exist in his own silent world, as if in contemplation of the role he would play this evening. His vote against the project would not count much—nine of the council’s eleven members, including Mayor Ed Garza, had already told reporters they would back it—but what he said in opposition to it, and how he said it, might count a great deal. Until now, Julián’s actions on the council had been relatively inconsequential. He had stuck by his principles but for low stakes: on issues involving trees, historic buildings, senior citizens’ centers, neighborhood policing programs, bicycling routes, family-friendly parks. The PGA issue was different. If the council created the special taxing district, the developer, Lumbermen’s Investment Corporation, would get to collect and retain all of the property, sales, and hotel-motel taxes for the next fifteen years—an estimated $52 million gift from the city in exchange for the jobs and tourism the project would generate. It was a Rosie Castro kind of issue, a classic case, in Julián’s eyes, of elected officials bowing down to corporate interests.

The debate had already caused him to leave his job at Akin Gump. On two previous occasions, the firm, which represents a list of moneyed players who do business with the city, had asked him to abstain from voting on matters in which he might have a conflict of interest involving the firm’s clients. Then, the firm asked him to stay out of the PGA vote because the developers’ proposed contract with the city had been drafted by the firm’s attorneys. Already feeling constrained, Julián had a gutsy idea. In January he consulted his brother, who had left the firm five months earlier, then typed out an e-mail announcing that he was quitting his $75,000-a-year job, one that any aspiring young attorney would have killed for. (His original salary, like Joaquin’s, had been $110,000, but he had arranged a deal in which he earned a smaller paycheck in exchange for time off to attend to his duties as councilman, for which he makes $20 a meeting.)

This night would make all of it worthwhile: He was now free to speak out, although his chance would not come until after midnight. He listened patiently to the opponents’ contention that the city would be subsidizing the pollution of the county’s main source of drinking water, since the 2,800-acre project would rest over a sliver of the Edwards Aquifer Recharge Zone. The rebuttal by the city’s various chambers of commerce was that the project was environmentally safe and that the alternative—the construction of some nine thousand residential homes on the same property—would yield far worse levels of pollution. When Julián’s turn finally came, he spoke not in the voice of his mother’s generation, as an aroused activist, but in the voice of his own making—as the skilled lawyer that life’s increased opportunities had allowed him to become. He called two of Lumbermen’s representatives to the podium and grilled them, after first thanking them, sarcastically, for staging “a wonderful public relations campaign.” He challenged the argument that single-family homes would pose a greater environmental threat than the resort and raised the point that the city could exert its regulatory power over lawn fertilization.

“Ju-lián! Ju-lián! Ju-lián!” The crowd was ecstatic. But the young councilman wasn’t through. He raised questions about the way the taxing district was structured and then, for dramatic effect, whipped out a stack of audiotapes he had concealed under the table and held them in the air. They contained, he said, the proceedings of a state senate committee hearing held two weeks earlier on the subject of taxing-district abuses. In the end, only one council member joined Julián in voting against the project; the council also flatly rejected his motion to let the matter be decided through a public referendum.

But his side would live to fight another day. In the following months, an impressive coalition of environmentalists and social-justice activist groups like Communities Organized for Public Service collected more than the 68,023 petition signatures required to force a referendum. Rather than face the voters, the project’s backers recently withdrew their original proposal and have entered negotiations on a compromise that deals with some of the critics’ objections. Of course, all of this was in the future when Julián Castro went home after the council meeting that April night. But the blooming romance between public and public servant was already palpable, underscored by a set of red handwritten posters somebody had abandoned in the lobby outside the council chamber.

“Integrity, Character, Promise. Julián Castro for Mayor.”

ROSIE CASTRO IS WEARING HER “Julián for District 7” T-shirt again, the one that’s white and maroon-turned-brown from the washing. Between her two sons’ campaigns, she has accumulated a wardrobe of political attire and has earned the right to wear it for reasons that go beyond motherhood: She was Julián’s campaign manager and holds the same position with Joaquin’s campaign as well. She is the reason many of the Castro brothers’ supporters believe in them passionately. She serves, as Joaquin puts it, “kind of like a guarantee on a loan. People know that they’re gonna get paid back.”

We’re trying to have lunch at Salsa Mora’s, a popular West Side eatery where the waitstaff already knows to begin preparing a chile relleno when Rosie appears. But it seems every other time the door opens today, in walks somebody she knows. “Congratulations on the boys,” they’ll say. Or, in a triumphant whisper, a wife will gush about her husband: “I just talked Tom into [block-] walking with the boys!”

One of the people to enter this afternoon is Henry Cisneros, the former mayor, who has known Rosie since their Catholic elementary school days. He is trailed by a troop of business and government types, but he pauses for a moment to chat by our table for two. “The boys are doing well,” he tells Rosie. “I know you must be very, very proud.” Towering over us in a blue-and-white plaid shirt and an orange tie, he apologizes for his tiny, red, watery eyes—the result, he explains, of recent eye surgery. And then, after some unmemorable conversation, he says of the older twin, “He came out very well on the PGA issue.”

Cisneros later explains to me how he views Julián’s politics so far: “I think Julián’s position on the council, especially on this PGA matter, has assumed the proportions of a long tradition in San Antonio—which one might say is the tradition of Henry B. Gonzalez, of Bernardo Eureste, of Pete Torres, of Maria Antonietta Berriozabal—as the person of conscience. As the person who is the sort of protector of the grass roots, community-based person, who is willing to call it as he sees it no matter where everybody is, whether it’s the political community or the business community.” It is notable, however, that among the role models Cisneros cites for Julián were some of his own strongest critics—and that two of the four, Torres and Berriozabal, lost races for mayor. When I probe him on Julián’s future, he says, “It’s still too early to tell if that can make him mayor of San Antonio or governor of Texas. But I think Julián has immense promise. His training as a lawyer gives him a measure of moderation. He’s honest and smart, which I think are the two most important qualities of a politician.”

Julián’s long-term challenge, as Cisneros sees it, will be whether he can avoid the label of a populist politician who has less to offer other segments of his constituency. It is a question I had asked myself as I watched Julián do his work on the night of the PGA vote. He tells me he’s not strictly anti-development, but something about the way he poked holes in the developers’ proposal suggested that he enjoys the feeling of single-handedly taking on the big system. He believes he can work well in the middle, but on the council, where he has shone is on the left, mostly alone. Julián knows this himself, and so he is already expressing support for a PGA Village compromise without the special taxing district, even if it’s built over the aquifer.

Striking a balance will be the key to Julián’s and Joaquin’s political success in other ways. Texas is still a place where ethnic minorities who are running for office are assessed first and foremost by the color of their skin—witness Tony Sanchez and Ron Kirk, the Democratic nominees for governor and U.S. senator, respectively—and held suspect as people who might be tempted to pander to their ethnic community. “To me,” says Julián, “the ideal would be for people to be able to run based on their ideas but still mean something to the community they come from, because that’s also part of what inspires people.” This is the role Cisneros once played for him. And yet, Cisneros’ case is illustrative of the ethnic quandary: While he developed broad electoral appeal in his hometown by focusing on jobs and economic development rather than on Mexican American issues specifically, the national media, he says, wanted to make him the Hispanic Jesse Jackson. “I didn’t get invited to the Today show because I was the mayor of San Antonio,” Cisneros recalls. “I got invited to the Today show because I was the highest-ranking Latino spokesperson on a particular issue and I was the mayor of San Antonio.”

The twins’ own stand on ethnicity and politics is influenced by their dual experience of growing up in a Chicana activist’s home while receiving their education and training at some of the nation’s most elite mainstream institutions. As they see it, it is a privilege to no longer have to fight solely for ethnic rights, and they honor the dirty work that their mother’s generation carried out to make that position possible. Luis Fraga, the twins’ former mentor at Stanford, says, “I see them as clearly combining the best of the outside critic and the best of the traditional insider. Their reality is the reality of Hispanics, of Mexican Americans, of Chicanos in San Antonio. But it’s also [Leland] Stanford, the robber baron. And Harvard—even more! And the walls of power and privilege at Akin Gump. And now the city council of San Antonio.”

Finally, the Castros will have to figure out how to pace their political ambition so they don’t look like young men in too much of a hurry. Julián stole the title of youngest councilman from Cisneros by one year—Cisneros was 27—and knows that if he runs for mayor in 2005, when Ed Garza, now 33, will have reached his two-term limit, he will be 30 and likewise steal the title of youngest elected mayor. The Castros’ urgency to get places is highlighted by a stack of cardboard boxes Joaquin has in his room at his mother’s home (Julián bought his own house a few blocks away): Of the six boxes he brought back when he graduated from Stanford, four remain unopened. “It’s like that part of my life, moving away and coming back, hasn’t been entirely reconciled with the present,” he says. “We’ve always been in a hurry.” But when I ask him what he’s in a hurry to do, the younger twin is briefly stumped. “To achieve, I guess,” he responds slowly. “But I still don’t think that we have a specific plan. I’ve just always had a feeling, in politics, that things would turn out all right.”

Whether they eventually do or don’t, Rosie Castro vouches for her sons with the confidence of a mother who knows her children. “The heart—that they have now,” she says. “The values and the sense of who they’re working for—that they’re working for people and that that in itself is a privilege—that they’ve got down pat.” And so she remains close to their side, their staunchest friend, believer, companion. Like the night the three of them, along with two of Joaquin’s campaign aides and me, were dining at the venerable Mi Tierra restaurant at some unthinkable hour. Julián had ordered a bowl of menudo; his twin, chicken-tortilla soup. The place was classic San Antonio—all bright streamers and donkey piñatas and Mexican guitaristas serenading guests at their tables—and Rosie decided she wanted entertainment. When the musicians strolled by with their guitars, she took out a wad of bills and requested a tune.

First, they belted out “El Rey,” that classic ranchera anthem to the Mexican macho that some of us Mexican Americans sing as effortlessly as we recite the Pledge of Allegiance, if often with a sarcastic smirk. “They like this song,” she said. “Their grandmother used to sing it to them.” Then the Castro brothers made the second request, and the musicians launched into a decidedly more lyrical bolero. Yet another incongruity: The verses about tortured love hardly fit the image of two highly educated, non-Spanish-speaking, moving-up-in-the-world young men. But it turns out they had learned the song in a middle school mariachi class. So the twins watched the musicians and became lost in the poetry, Joaquin sitting back with his arms crossed over his chest and a tight grin on his face, Julián leaning forward and tapping his fingers on the table, mumbling along what he remembered. However fleeting it might have been, for that brief moment the Castro twins were, indeed, just two boys. And their mother turned to me with a satisfied smile.

“Either way,” Rosie said, lifting her eyebrows, “win or lose—we celebrate.”

- More About:

- Politics & Policy