This was going to be an article about teaching. Specifically, it was going to be about an influential yet little known retired professor in East Texas who has arguably the most impressive roster of alumni in the state.

But when I looked at his work, I realized that this story needed to be about more than teaching art. This is about art itself, why we make it, and ultimately, what makes life worth living.

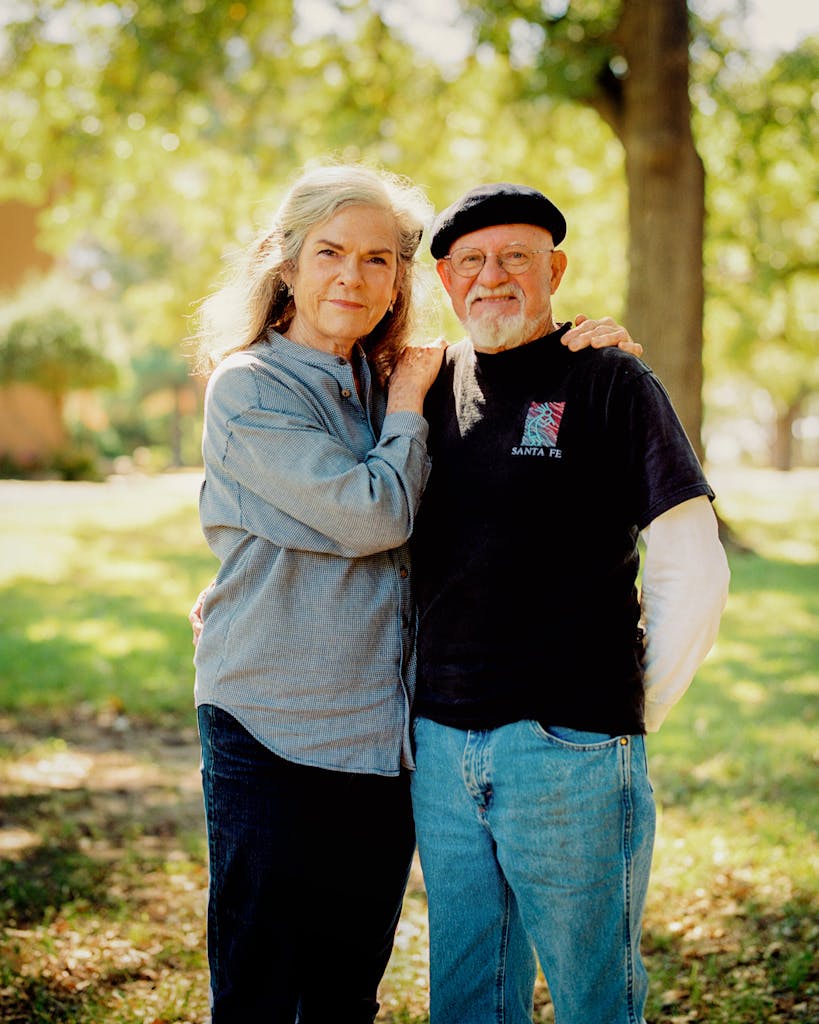

Lee Baxter Davis is an 83-year-old living near the small town of Greenville, about seventy miles northeast of downtown Dallas. You’ve probably never heard of him, unless you follow the art world closely, in which case you may know vaguely about “that guy who taught Trenton Doyle Hancock and Robyn O’Neil and, before that, the guys who designed Pee-wee’s Playhouse.” His artwork doesn’t get shown much. It doesn’t sell much. He’s got flat files jammed with hundreds of ink-and-watercolor drawings that he’s made over the years. Mostly they’re strange and dense with layered imagery. The very best of them are masterpieces.

Consider Bread Upon the Waters, a piece from 2014. At first glance, it’s busy, the faces cartoonish and askew. But then you see the expert draftsmanship in Davis’s depiction of the redheaded bird, in the fleshy wrinkles in the squirrel’s face, in the bee at the center. The central figure (the bald, bespectacled guy with the goatee) is Davis himself, staring wearily at the viewer. He’s caught in a “duality,” a word Davis uses often. On the right are worldly concerns, represented by mysterious costumed men who seem to be vying for his attention. On the left is the spiritual world—the archetypal animals, a pocket watch measuring time’s finitude (or infinitude, or both), a shadowy woman’s nude torso in the background. Splitting the composition down the middle, brightly colored plants and flowers curve toward the left, and Davis points a handgun toward the right, as if to half-heartedly defend himself from that side. His head is surrounded by little clouds of floating bubbles, like the yeasty scum that forms on the surface of a stagnant pond—the “bread upon the waters” of the title?

But wait, there’s more: Who are those tiny soldiers wearing kilts and pith helmets? What’s up with the apprehensive Kewpie doll? Why does the bee appear to be collecting pollen from the crotch of the man wearing a Venetian mask? Davis never gives the answers, in this or any of his works. He just packs them with odd, comical vignettes, every square inch almost compulsively covered. His former student Lawrence Lee likens Davis’s works to a bountiful feast: “You got lobster, you got steak—there’s nothing on the plate that you don’t like. There’s nowhere for your taste buds to rest. It’s almost overwhelmingly good. Which makes it hard to handle.”

For all their crowded, comic-book weirdness, though, Davis’s works are connected to a history of spiritual signifiers. He’s not interested in the trivial or goofy; he’s obsessed with our species’ most fundamental questions. It’s why he dissuaded one student from drawing a stack of Coke cans for no reason other than the student liked Coke. Davis is focused on the stuff people think about on their deathbeds. Which is just one of the reasons you probably haven’t heard of him.

For an artist to make a living exclusively by selling art—something very few of them actually do—a lot of things have to go right. Their art has to be in fashion. They have to hustle and pound the pavement and sell themselves. They have to say and think the right things.

Davis has not done any of that. He’s lived most of his long life in rural northeast Texas. He hasn’t hung around Dallas or Houston, much less New York City or Los Angeles. He’s never tried to moderate his East Texas accent, a high-pitched, nasal collection of soft consonants. He is profoundly religious. He has no interest in cool.

There’s a wrongheadedness in all this if your goal is stardom. But while wrongheadedness can mean self-sabotage, it also can mean independence and freedom. It means going against the grain, making art for reasons that have nothing to do with having an art career. “If you’re thinking, ‘My artwork is a commodity that I want to sell,’ then you have got to be able to present that commodity and sell it,” Davis told me recently in the small, cluttered studio above his garage. “The worst crap that I have ever done is when I get to thinking about that.”

This was at the end of a long conversation in which the jovial, diminutive professor—“I put on a pretty good performance about being one mean little guy,” he joked—gestured excitedly in the air as he described both the “sensuous” skeletons of the armadillos he’s had to kill recently (they’re tearing up his yard) and how drawing those same armadillos from memory is a pathway to divine inspiration. Davis’s work is ultimately about the kinds of things that make a lot of artists and gallerists and patrons squeamish: devotion, the search for meaning, an unabashed love for life, for the universe, for God. If you go about this work as religious hermits do—as Lee Baxter Davis has done—it can be a tough, lonely road. Because you have to do everything wrong.

1. Make the Wrong Art

There was a time when the only art that mattered in America was abstract. Figurative art—art with recognizable subject matter—was pretty much taboo in the seventies, when, as the Dallas painter John Pomara puts it, “[Donald] Judd and his gang were running the art world.”

At that time, Davis was in his thirties and already laboring away in Commerce on a massive body of allegorical drawings. He had no interest in abstraction, which he calls merely “solving a design problem.” He wanted his work to explicitly, unambiguously mean something.

So he made figurative ink drawings, often also painted with watercolor, that spring from a rich legacy of mythology, science fiction, botanical engraving, and literature. His self-described “swamp rabbit mysticism” combines his uncanny drawings of plants and animals with human narratives of war, sex, and death. Soldiers, guns, and hand grenades appear alongside a female archetype—based on his wife of 57 years, Waynette—who appears variously as a warrior, a mother, and a temptress.

Davis really shines when he’s drawing animals from every phylum and class you can think of: insects, reptiles, fish, birds, hogs, and dogs, to name a few. He grew up dehorning cattle and raising pigs, and he speaks about how he saw a connection between his own “animalness” and “the animalness of the animals” around him. “I began to see them as kind of like beasts of burden,” Davis said. “The animals could transport you somewhere. But I’m not just talking about transporting you somewhere in real time and real space. I’m talking about transporting you somewhere that would give substance to mystical ideas.”

The central idea Davis grapples with is the duality of “the barking dogs of reason and the maelstrom of mysticism,” which in his prime was regarded by art’s gatekeepers as laughable compared with the austerity of minimalism and the aloof wryness of pop art. Equally unfashionable at the time—think of Judd’s machine-made boxes and Warhol’s screen prints—was the artist’s hand. Draftsmanship was thought of as a secondary if not tertiary skill. And Davis is above all else an extraordinary draftsman.

“Lee is facile,” said James Surls, Davis’s college roommate and an internationally recognized artist from East Texas. “I think he could forge one-hundred-dollar bills. He’s that good.” Davis’s former students compare him to William Blake, Hieronymus Bosch, Albrecht Dürer, and Otto Dix. The Houston-based artist Trenton Doyle Hancock described seeing Davis’s work when he was a student at A&M-Commerce in the nineties: “I saw a range of mark-making and decision-making that I frankly had never seen before. It went beyond being able to draw really well. The fact that he could optimize modest materials and turn this thing into magic, I thought, ‘I have to learn this.’ ”

True, Davis was not the only artist in the seventies making figurative work. Philip Guston, whose retrospective is on view at the Museum of Fine Arts Houston, was famously ostracized and dropped by his galleries when he gave up on abstraction. And figurative art—including work that, like Davis’s, was partially inspired by comics—went on to have comebacks in the eighties and again in the aughts. But by that time, Davis had already dug in, living unnoticed near Greenville.

2. Live in the Wrong Place

East Texas is not where you live if you want to become a famous artist. Davis grew up there, moving between small towns with his paternal grandparents, who raised him. He left for a crucial spell as a young man, joining the Army in the aftermath of the Korean War and traveling overseas to Europe and Asia. Upon returning, he got his undergraduate degree in printmaking at Sam Houston State University, in Huntsville, and he used the GI Bill to get his master’s at the esteemed Cranbrook Academy of Art, in Michigan. Then he returned home.

Davis says the only reason he ended up staying is that he got a teaching job at what was then East Texas State University (it became A&M-Commerce in 1996). In 1965 he married Waynette—herself an accomplished artist—and in 1971 the young couple settled down with their two small children on a thirty-acre parcel of land, just a short drive southwest of the university, where they live to this day.

Davis’s decision to live in such an obscure location has turned out, in some ways, to be a blessing. The area was, as another of Davis’s former students, the artist Greg Metz, remembers, a place of abandoned sharecropper shacks and broken-down cotton gins. “It was a boring town where there was nothing to do but make art,” adds the artist Gary Panter, another ETSU alum. Far from the major centers of the American art scene, East Texas meant freedom from scrutiny and the whims of fashion.

The school was a lifeline for smart local kids. In the seventies, ETSU was the most exciting art school in the region, much as the University of North Texas would become a couple of decades later. This was during the first wave of ETSU’s most famous students, who were known informally as the Lizard Cult, for reasons nobody can agree on in retrospect. Ric Heitzman, who would go on to codesign Pee-wee’s Playhouse with Panter and others, compares ETSU then to Black Mountain College, the legendary art school in North Carolina, adding, “It’s odd that [ETSU] was so obscure.” Hancock and Robyn O’Neil, who studied under Davis in the nineties, were part of a second wave of illustrious alumni. “Even if I had gotten into larger schools in different parts of the world, I can’t imagine coming out of those places with as good an education as I got at ETSU,” Hancock said.

Former students describe Davis bounding around the classroom, jumping on desks in his combat boots, delivering rambling, erudite lectures that digressed into whatever he was reading about at the time: cave art, hieroglyphics, book engravings, philosophy, theology, literature, and art history. “I went to graduate school at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, and I never met a professor that was quite the intellectual that he is,” Heitzman said.

His former students give the impression that Davis loved working with them as much as they did with him. He encouraged them to tell stories, to leave space for magic and questioning in their work. He gave them confidence and treated their raw, unformed talent seriously. Many of Davis’s students were poor; a couple told me they were cut off financially by their parents when they decided to study art. They took a leap of faith on art, and luckily, their professor shared that faith.

3. Believe in the Wrong Things

In art, religion has been out of fashion for at least a couple of centuries. Indeed, many art enthusiasts seem to have traded worshipping a deity for worshipping art, something Davis’s beliefs do not permit. “Art is an illusion,” he said. “It can never be mistaken for a religion. Please do not endanger your immortal soul by worshipping an artwork.” For Davis, a devout, practicing Catholic and an ordained lay deacon, art merely illustrates spirituality. It is not spirituality itself.

Such overt religiosity is rare in the art world. But his faith aside, even if Davis had lived in Manhattan all these years, his personality would have been wrong for stardom. He is an iconoclast, but for all his erudition, you get the sense that he’s fundamentally a homebody. Happily married, happily teaching, happily making the work he wants to make—there has never been much incentive for him to play the game and cultivate a wider reputation.

And yet: all artists desire an audience. Several of Davis’s former students mentioned how it has frustrated him over the years that he hasn’t gotten more recognition. “He always said to us, don’t do what he did,” said Hancock, who is represented by galleries in New York, London, and Los Angeles. “Think about the larger aspect of what it means to have a social relationship in the art world.” Davis himself laughed as he put it to me more bluntly: “I always warned ’em, I said, ‘Look at me. You want to be a success? Here I am, teaching you in this little third-rate university! Go ahead, copy me, see where it gets you!’ ” But he also said, “If you really want to know yourself and be a spiritual being, you can be any kind of sumbitch you want to, but don’t be a success. And I managed to do that!”

For reasons that boil down to his refusal—or his constitutional inability—to promote himself, Davis never hit the big time. His trove of artworks may never make it into the history books. But how big a sphere of influence does one need, and how should it be measured? In short: why do artists make art, if not for an audience? Panter responded to this question elegantly: “If we are lucky, we get to make stuff to satisfy some inner necessity. Artists don’t need limos or people in black leather outfits taking selfies in front of their work. They need some time alone and art supplies and ideas and a kind and inspiring word to pass along.”

The search for meaning, the vulnerability of love—that is the realm occupied by Davis’s life’s work, stored in all those flat files in Greenville. And that’s what’s left in life when you strip away glamour and money and fame. Davis enjoys acclaim and mythic status among the hundreds of artists who were his students. Through them, his influence continues to ripple out all over the world. The artist Katherine Taylor, another former pupil, describes this unfurling impact as a “silent gift,” adding, “I hope that Lee can know how much he’s affected people that he’s never met.”

Rainey Knudson is an arts writer in Houston. She recently edited One Thing Well, a book about the Rice Gallery, and is now editing a book of essays from the online art journal Glasstire.

This article originally appeared in the December 2022 issue of Texas Monthly with the headline “How Not to Be an Art Star.” Subscribe today.

- More About:

- Art