Gary Cartwright left an imprint on Texas letters but also on many writers, editors, and staff associated with Texas Monthly over the years. Below are a few remembrances.

William Broyles—

In the fall of 1972, while Gary was working on a story about the elusive and enigmatic Dallas Cowboys star running back Duane Thomas for our first issue, I went with him up to Dallas. We hadn’t published anything. Nobody had ever heard of Texas Monthly. We were complete unknowns and we were banking on Gary to give us some credibility.

Gary took me by the Dallas Times Herald to see his legendary boss Blackie Sherrod. Blackie was a tough newsroom hidalgo who brooked no mediocrity and suffered no fools. He had been mentor to some the best writers of that generation, among them Bud Shrake, Dan Jenkins and Gary. I had just turned 28 and I was Gary’s new editor. I was doing my best to win his confidence. Blackie looked at me, took a puff of his cigarette, then turned to Gary and said, “Where’d you get the copy boy?”

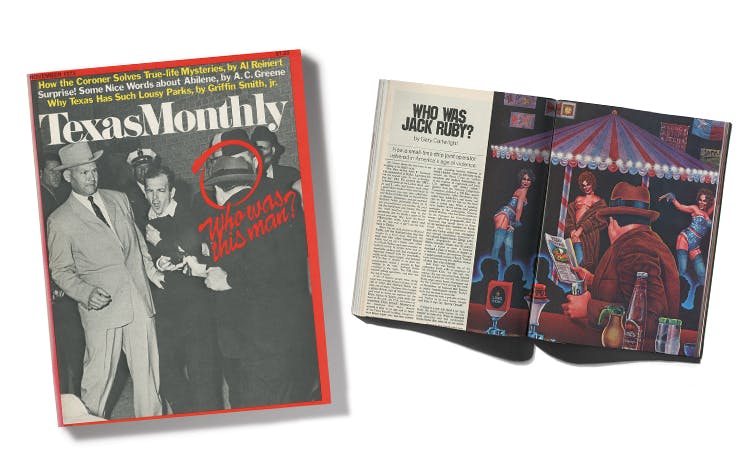

From the Times Herald, Gary took me on a tour of the underbelly of Dallas. We caught some strippers, I believe Chastity Fox was among them, heard tales of Candy Barr, Lee Harvey Oswald and Jack Ruby, and did a great deal of mind-altering substances, some of them legal. Everyone greeted Gary like he was the mayor. Those were Gary’s gonzo days with the Mad Dogs and the Flying Punzar Brothers, back when Hunter Thompson used to come to our poker games. Gary was superhuman in his endurance.

I was barely conscious when Gary took me by our digs, which were in Pete Gent’s apartment. Pete was a former Dallas Cowboy tight end. He was finishing up North Dallas Forty, a roman a clef about the underside of his Cowboys career that was made into a remotely recognizable film with Nick Nolte.

I collapsed on the bed. Gary went out. His last words were, “The party’s just getting started.”

The apartment was in the direct flight path of Love Field, then Dallas’s only airport. Every thirty seconds or so a plane would scream over just above the roof. I’d only been back from Vietnam three years, so on every flyby I had to fight the urge to yell “Incoming!” and hit the floor. Finally I went to sleep.

At some indeterminate hour I was shook awake by a huge guy with a Taxi Driver grin on his face. He was pointing a pistol right at me. This was Pete Gent, and apparently Gary hadn’t told him that I was his houseguest.

“Who the hell are you?”

I looked over at Gary, pleading for help.

“I’ve never seen him before,” he said.

Broyles was the founding editor of Texas Monthly and worked at the magazine from 1972 to 1982. He is a writer and a producer.

Gregory Curtis—

The best time I had with Gary was attending the Evander Holyfield–George Foreman fight in Atlantic City in April 1991. It was billed “The Battle of the Ages” because Foreman was 42 while Holyfield was only 28. Foreman had come out of retirement four years before. Since he was ancient for a boxer, Foreman’s comeback was greeted with scorn and laughter. We sent Gary to do the story and he came back a believer. Gary was right. Foreman won fight after fight, and now here he was, fighting to become the heavyweight champion of the world.

There were strong Texas ties to the fight. Foreman, of course, was from Houston, and Holyfield, although from Atlanta, trained in Houston. Both of us had visited the boxing gym in north Houston where Holyfield sparred against a series of big lugs who had been imported from around the country as pseudo Foremans. Gary had gotten to know Dan Duva, Holyfield’s manager, and I struck up conversations with George Benton, Holyfield’s trainer, who was a surprisingly elegant boulevardier-pugilist, a rare combination. In my living room, I still have a framed photo of me taking notes as Benton told me how Holyfield was going to win.

The fight was in the auditorium where the Miss America contest had traditionally been held. HBO carried the fight, so at ringside, preppy Time Warner executives and their wives in Ann Taylor suits sat uneasily next to flashy mob guys and their va-va-voom girlfriends. From where we were sitting in the distant press box, Gary looked down and made an observation I’ve found to be eternally true: “The worse the dye-job, the shorter the skirt.”

Curtis was editor-in-chief at Texas Monthly and worked at the magazine from 1972 to 2000. He is a writer and a teacher.

Evan Smith—

Gary Cartwright wasn’t just from another era—he was from another planet. Nothing about him was as expected. Many years before, he earned the right to be a head case, a prima donna, a raging asshole, but he was none of those things. He was gentle, elegant, patient, decent, generous, and greatly and visibly appreciative of all manner of little people. Whether he was writing about the Cowboys or his old guy sex life, he turned in consistently solid work and was enthusiastic about making it better—no pretense and no entitlement despite his elevated status. Maybe the best thing about him was that he never changed. He was who he was. He didn’t evolve and didn’t adapt. The Gary I met 25 years ago in the kitchen of Robert Draper’s house on New Year’s was the same Gary who told me, with real emotion, that he loved me on the day I decided to quit Texas Monthly. I loved him back. Still do. Always will.

Smith was editor-in-chief at Texas Monthly and worked at the magazine from 1991 to 2009. He is the CEO and co-founder of The Texas Tribune.

Gary Cartwright wasn’t just from another era—he was from another planet. Nothing about him was as expected.

Jake Silverstein—

One of the first stories I was given when I came to work at Texas Monthly in 2006 was a profile of the historian and illustrator Jose Cisneros by Gary Cartwright. I didn’t really know Gary at that point, but like many readers, I thought I did. His writing was so frank and revealing, and so alive on the page, that the time I’d spent marveling at the stories collected in Confessions of a Washed-Up Sportswriter had left me with the sense that Gary was my intimate companion. I thought I understood him. At least I understood his move as a writer, which was simple but profound: he just refused to bullshit you. Most writers rely on a little bullshit to get them through. Gary dispensed with all that. He left all that at the door. What you got was true and honest and bracing and sometimes, as is true of most forms of real honesty, a little weird.

So sitting down to work on his Cisneros profile, I felt like I was working with an old friend. Which is probably why I overdid the edit. The next morning there was a voicemail from Gary: two minutes of him yelling at me, objecting strenuously to some of the queries I’d sent him, questioning my reading comprehension, and just generally letting me have it. I was shocked—and then deeply rattled. I quickly called him back, nervous that I had messed things up right off the bat with one of the magazine’s most legendary writers. We talked. I apologized for my overzealousness, explaining that I was new and trying too hard. He apologized for overreacting and yelling at me. We talked about the quiet heroism of Jose Cisneros, who was 96 years old and still working. By the end of the call, I felt a certain bond with Gary, the kind that comes from the intimacy of anger and forgiveness. He’d been honest with me, letting his temper flare; and he’d been kind and compassionate when I called. I realized, happily, that Gary was just as allergic to interpersonal bullshit as he was to literary bullshit.

That’s always how I’ll think of Gary: someone who fought to let the honest truth get out, free of bullshit, free of qualifications, even when the honest truth was unpleasant. He was an inspiration to many generations of writers at Texas Monthly, someone who was read and re-read for clues about how to do what is seemingly easy but actually very hard: to write what happened.

Some years later, I went to him with a story idea: would he be willing to write a journal about dying? He could keep a diary of his final days, whenever they happened to arrive, and after he departed we would run them in Texas Monthly, giving him the last word. I thought this would appeal to his sense of the macabre. He stared at me for a while, not saying anything, considering it. Then he fixed me with a suspicious look and said, “How you gonna pay me?”

To the best of my knowledge, Gary never wrote that story (though we did pay him for it: a final victory for the washed-up sportswriter). If he had, I know this: it would have been straight and true.

Silverstein was editor-in-chief of Texas Monthly and worked at the magazine from 2006 to 2014. He is editor-in-chief of the New York Times Magazine.

![]() Brian D. Sweany—

Brian D. Sweany—

I first saw Gary when I was an intern in 1996. It seemed unbelievable that a legendary writer like himself was standing a few feet away from my cubicle, chatting with an editor and wrestling with an armload of mail I doubted he would respond to. He had long been a hero of Texas letters, one of the first writers the interns really read deeply, and he was still going strong. I wanted to introduce myself, but I chickened out. I couldn’t think of anything worthy enough to say. At that time, I had begun reading the Texas Monthly archives, and the first story I read by Gary was “Is Jay J. Armes for Real?” The piece began this way: “Jay J. Armes was running short on patience and long on doubt. He was slipping out of character. It was possible he had made a mistake.” How could I not keep reading? Gary’s prose was electric, inventive, and a little bit dangerous. I had never read anything like it. I got in the habit of photocopying stories I liked and collecting them in a three-ring binder. I copied all the stories Texas Monthly had published about LBJ, for example, or the Dallas Cowboys. Over the years, I probably had fifteen or so binders, which I’ve kept to this day. Gary was the only staff writer to have an entire binder dedicated to his work. He’ll be missed like no one else.

Sweany was editor-in-chief of Texas Monthly and worked at the magazine from 1996 to 2016.

Paul Burka—

It is hard to imagine that Gary Cartwright’s pen has fallen mute. He was the most naturally gifted of all the Texas Monthly staff writers. The hallmark of his writing was a biting wit, and heaven help those who fell victim to it.

He himself was a mythic Texas character: hard drinking, hard driving, with an encyclopedic knowledge of the state. Like many great writers, Gary began his journalism career as a sportswriter, his start being with the Dallas Morning News in the years when the Cowboys were riding high. He had the most comprehensive understanding of Texas of any writer on the staff, in part because he spent so much time with its political and literary icons, chief among them Ann Richards and Bud Shrake. In due course, Gary absorbed a comprehensive knowledge of the state that ultimately produced a long list of memorable articles. My personal favorite was his story about the Waggoner Ranch, which ultimately fell victim to family infighting.

Most of all, Gary was Texan to the core. He could write about anything from beer to barbecue to sports, and it would invariably come out great. It is an awesome legacy. His talent was that massive.

Burka was a staff writer and editor at Texas Monthly from 1974 to 2015.

![]() Jan Reid—

Jan Reid—

In 1965 I was a twenty-year-old watching the Dallas Cowboys trying to turn the corner and stop being a woeful expansion franchise. Playing in Dallas, with time running out, they were one yard away from beating Cleveland’s then-mighty Browns and their dominant runner, Jim Brown. Dandy Don Meredith, the handsome dashing Dallas quarterback, dropped back and threw a pass over the middle straight into the brisket of an astonished Cleveland linebacker. Ye gods, I raged, was that the worst and dumbest play ever? (Actually, it was reenacted the exact same way by the Seattle Seahawks’ quarterback Russell Wilson and head coach Pete Carroll in a recent blown Super Bowl.)

The next day, in the student center of Midwestern State University in Wichita Falls, my first hometown, I picked up the sports section of the Dallas Morning News. Tom Landry had made the bonehead call but he let Dandy Don take the fall. His orders were to throw to a spot, where his receiver—not a linebacker—was certain to be. The Dallas writer covering the game offered a take on an opening paragraph once penned by a famous Chicago sportswriter, Grantland Rice, in praise of a Notre Dame team with a full house of great running backs he nicknamed the Four Horsemen, as in the scripture in Revelation. The Morning News version went: “The Four Horsemen rode again Sunday in the Cotton Bowl. You remember their names: Death, Famine, Pestilence, and Meredith.”

I hooted and for the first time ever looked at a byline to see who could have written that. One Gary Cartwright.

He was as wrong as all our legions of suffering Cowboy fans were. Meredith had every right to be wounded, but in practice the following week he called off the Dallas players who wanted to take a little hide off Mr. Smartass Cartwright. “Just doing his job,” Meredith said, and he and Cartwright remained friends the rest of Dandy Don’s life. The last time he called Gary, it was not to talk but just to sing him a pretty song.

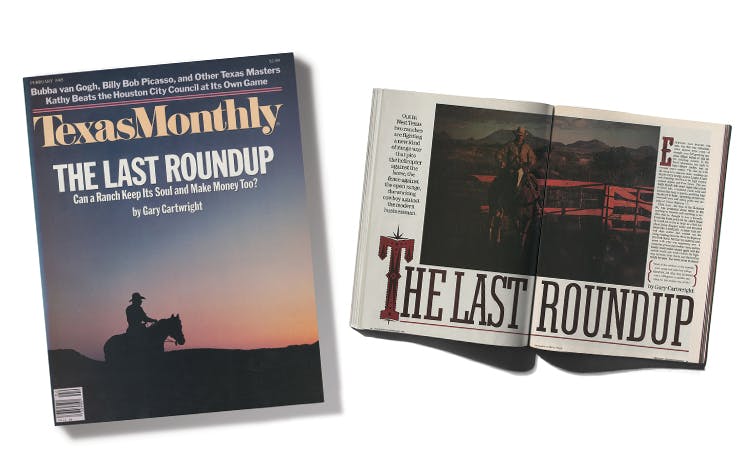

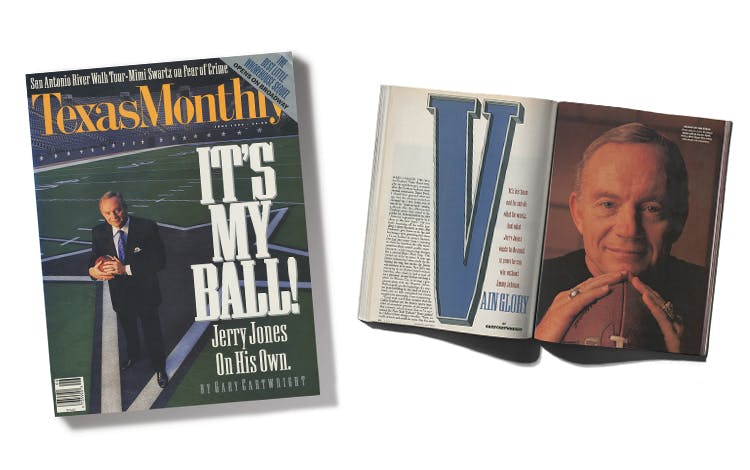

Gary made his first bones as a magazine writer, following an unpleasant 89-day stint at the Philadelphia Inquirer, with a Harper’s essay titled “Confessions of a Washed-Up Sportswriter.” But as leader of the pack in the very first February 1973 issue of Texas Monthly, he contributed a profile of the silent star running back of the Cowboys’ first Super Bowl winner called “The Lonely Blues of Duane Thomas.” Among his many other talents, Gary was one of the best sportswriters in the English language. And though he could be merciless about the Arkansas carpetbagger owner of the Cowboys—see “The Devil and Mr. Jones” (October 2001) and “Go Fire Yourself” (October 2007)—he never stopped pulling for the ’Pokes. Even when they were truly awful.

For instance, one Sunday we were driving back from Galveston, where from a beat-up shrimp boat, with flowers, his reading of a beautiful poem, a perfect rainbow in twilight out across the bay, and a dolphin’s leap off the stern, he had released the ashes of his beloved wife Phyllis. He was riding in the back seat as we passed Lagrange, and it seemed like a mellow and reflective time to watch the terrain roll by—until suddenly he was yelling at me because the radio cut out on a Dallas game with the Indianapolis Colts and I couldn’t find another station.

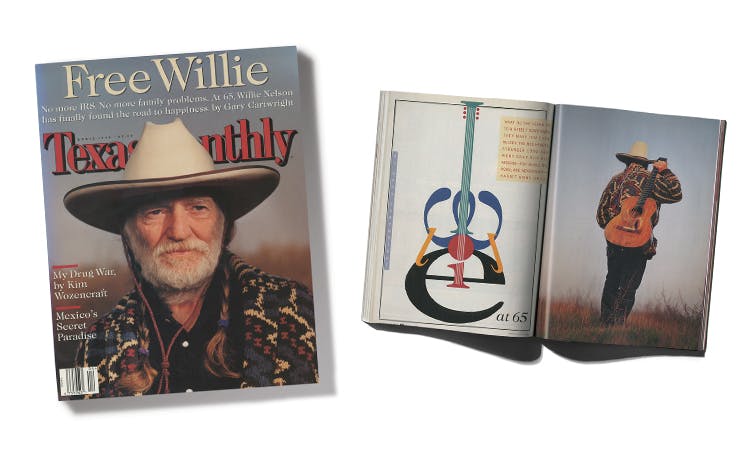

Football wasn’t his only sporting interest. He told me that the very best thing I could do in Houston some Sunday morning was to go to a little church and watch George Foreman preach. He was right. But another time, in the Olympics, a United States hockey team was on the verge of beating Canada, an event as unexpected and unprecedented as that time the Americans beat the Soviet Union team. My wife, Dorothy, and I had the game on and were caught up in the drama, and she kept asking me what was going on.

“I don’t know the rules,” I said.

So I got out my trusty cell phone and called the master.

“How would I know?” Gary answered.

“What?” I cried. “You wrote a novel about hockey!”

It was a commissioned 1976 paperback original called Thin Ice.

“Yeah, but I never saw a game,” he explained. “It was about a blind goalie.”

Jan Reid, a contributing editor, has written for the magazine since 1973. He is the author of ten nonfiction books and three novels.

Nicholas Lemann—

When I arrived at Texas Monthly, in 1978, Gary Cartwright was our big-name writer. He was a member, along with Dan Jenkins and Bud Shrake, of a kind of Greatest Generation of Texas magazine writers; Gary was the one who had stayed in Texas and kept his home state as his main subject. He seemed to me to be a glamorous figure who would go anywhere to do any story—unless he’d done it already. At that point he was deep into chronicling the doings of the Chagras, the especially wily and ruthless family of drug dealers. And for all his exalted status, he was unfailingly welcoming and helpful to newly arrived young staff members like me. He put across a sense that there was nothing better in the world to be a reporter covering a story in Texas—except maybe repairing to the Raw Deal after you’d finished. Gary was as far as you could possibly get from pretentious, so he would never, ever have consciously tried to be “inspiring”—but that’s what he was.

Lemann was a staffer at Texas Monthly from 1978 until 1983 and contributed occasionally after that. He is now a professor at the Columbia Journalism School and a staff writer for the New Yorker.

Stephen Harrigan—

As a writer who struggles with the vice of fastidiousness, I’m always on the look-out for passages that, while perfect, are seemingly unforced and naturally-occurring. Here is what might be for me the ultimate example, a description by Gary Cartwright about what it felt like to have a heart attack: “It’s not a sharp, stabbing pain but a dull, tight ache across the chest, as though a bear were sitting on you reading the sports page.”

The sentence was in a letter that Gary wrote to his friends in 1988 to let them know about his recent heart surgery. It was later reprinted in his book Heartwise Guy. Sometimes you remember all your life exactly where you were when you encountered a great work of literature. For me, that was the case with this sentence. I was sitting on a couch in my living room, near the foot of the stairs, afternoon light streaming in from the north-facing window. A bear sitting on your chest reading the sports page. Could anybody but Gary Cartwright have come up with that? The surreal yet somehow perfectly natural presence of the bear, his placid indifference to the suffering human beneath him, his absorption in—but here I am trying to perfect a sentence again. When will I ever learn what Gary Cartwright seemed to know instinctively? You just think about what’s true, or what’s funny, or what’s scary, and you write it down.

Harrigan, who has been contributing to Texas Monthly since 1973, is a novelist and writer-at-large for the magazine.

Robert Draper—

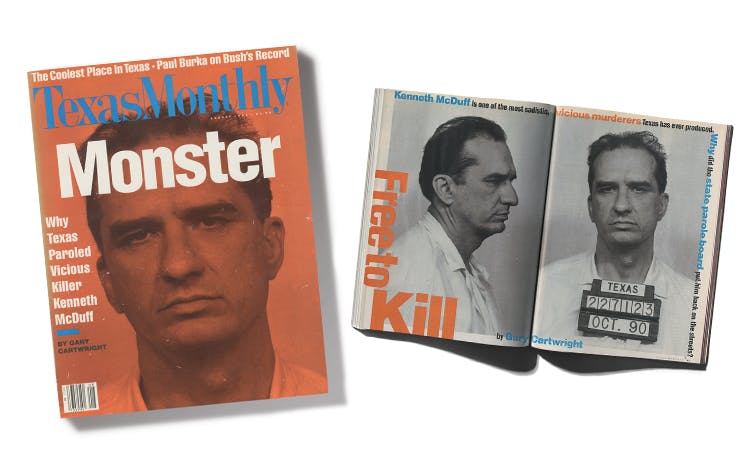

About fifteen years after reading the deathless passage of Gary Cartwright’s that first stirred in me the desire to be a magazine journalism—“If there is a tear left, shed it for Jack Ruby. He didn’t make history; he only stepped in front of it”—I met the old cuss for the first time.

I’d been led into his newish office room in the magazine’s Austin headquarters at 701 Brazos, where Gary was still trying to figure out how to use the voicemail apparatus on his office phone. His gaze of contempt at the technology softened when he saw me. At the time I was a freelancer and finishing up a piece about his buddy Willie Nelson, and I was frankly terrified that Gary would feel me unworthy of the topic. Instead, he treated me like a long-time colleague. The condescension I kept waiting for he reserved exclusively for the office phone.

Among the dualities in his character was that he could be stubbornly old-fashioned and young at heart all at the same time. In story meetings, I came to relish his terse declarations like, “Nothing’s off the record!” Once he observed that someone’s story could use “a sider.” Several of us squinted at each other. Did Gary mean the story needed a co-writer? A side order of fries? Then it dawned on us that he was apparently using an old newspaperman’s term for “sidebar.” A few of us used to imitate his gruff cadence, how he bit off his words like beef jerky. I’m pretty sure he knew. Gary was always in on the joke.

While reporting, Gary preferred neither to take notes nor to tape record a conversation. Instead, he would ask questions, listen intently, and then retreat to his car and scribble out what he had just heard. Though this might seem like a precarious way to conduct an interview, more than one of his subjects told me that he had captured their words to perfection.

Gary was not a glad-hander. He was not particularly impressed by authority or wealth. Though he was a man of considerable ego who enjoyed his words being read like the rest of us do, he harbored no desire that I know of to be honored as the literary giant that he happened to be. What motivated him above all was the process of reporting and storytelling. The demons that bedeviled his personal life seemed to back away the moment he picked up his pen.

He saved his most painful story for last, penning his memoirs in 2014. There was nothing left for him to say after that. Now he recedes from us like Jack Ruby, Candy Barr, Benny Binion and the other broken figures he enshrined. Maybe that’s what explains Gary Cartwright’s greatness—that he treated us all as equals.

Draper was a staff writer at Texas Monthly from 1991 to 1997. He is a writer-at-large for the New York Times Magazine and a contributing writer for National Geographic.

Prudence Mackintosh—

I wish I had a great story to tell. I do remember that my mother-in-law Jane cancelled her subscription after she read Gary’s story about having sex on an airplane.

Prudence Mackintosh, a writer-at-large, has written for the magazine since 1973.

Peter Applebome—

Contemporary real estate gospel says it’s easier to sell a house with a corpse rotting in the basement than one with bookshelves full of books. So last June, in the interest of decluttering, supporting the local library and getting rid of evidence of being terminally over the hill, I was throwing out books.

Out went War and Peace and Humboldt’s Gift. Tossed heedlessly into cartons were Ronald Reagan: His Life and Rise to the Presidency and The Semi-Official Dallas Cowboys Haters Handbook (still hate them, but the 1984 iteration seemed a little dated) and many, many dozens more. In the midst of this slaughter of the innocents I came upon Confessions of a Washed-Up Sportswriter. Needless to say, it did not get thrown out. Instead, I sat down, opened the book and found myself gobsmacked once again by Gary Cartwright’s neon-lit cavalcade of primal Texana, like falling through a gin-soaked looking glass. Cowboy Hardley’s penchant for gravy over cantaloupe at the Lavender Cafeteria in Fort Worth. Otis Crater and the pitbulls of “Leroy’s Revenge.” Every single syllable of Gary’s imperial profile of Candy Barr, which has to rank with the greatest magazine profiles ever. I have no idea how Gary did what he did, but no one ever sucked up as much caliche dust, hog sweat, cheap perfume and piss, so much vanity, foolishness, pride and prejudice as Gary did. In his postscript to his classic piece on the death of Bigun Bradley, the Marlboro Man, he noted the story was inspired by a single paragraph in the Daily Texan. “The mystique was finding out who he was and how it happened. The old chase. You’ve got to have a taste for it.’’ Did he ever.

Applebome was a staff writer from 1982 to 1986. He is deputy national editor at the New York Times.

A few of us used to imitate his gruff cadence, how he bit off his words like beef jerky. I’m pretty sure he knew. Gary was always in on the joke.

Helen Thorpe—

Shortly after I started working at Texas Monthly, I asked Gary for advice about a story I had written. Honestly, it wasn’t very good. He told me that I must be a writer a lot like him; his early drafts generally represented just the gist of a piece. He didn’t find the exactly right words until the second or third draft, he added. Somehow, he made me feel good about writing a crappy draft, in other words. It was the nicest thing another longform writer could possibly have said to somebody just starting out in the genre.

A journalist living in Colorado, Thorpe was a staff writer from 1994 to 1999.

David Dunham—

Gary was once asked what was the favorite headline he had written when he was in the newspaper business. Without hesitation, he said, “Cops Eat Kid’s Pet.” The story behind the headline was that the Fort Worth police had discovered a doe that had been hit by a car, still warm, and decided to have an impromptu venison barbecue on the spot, which was in a city park. What they didn’t know was that the doe had been taken in by a family that lived nearby as a fawn and bottle-fed and raised to become the yearling that it was when it jumped the fence and had the bad luck to get hit by a car. The family happened to walk by the barbecue, figured out that their pet was the main course, called the newspaper, and the rest is headline history.

Dunham is the publisher of Texas Monthly. He has been with the magazine for 38 years.

Dick J. Reavis—

In 1979, after the magazine published a story of mine about the Bandidos motorcycle club, Cartwright invited me to lunch. His purpose was to give his blessings to me. I concluded that I’d been accepted into the club of Texas magazine writers, despite my freelance status. He and I began running into each other, often at the Raw Deal, a cafe that stood on West Sixth Street. Once, after I’d finished a particularly long story, I summed the courage to brag on myself, a privilege of club members—or so I supposed.

Those were typewriter days. When writing long stories—5,000 to 10,000 words for TM—most of us typed only one paragraph to a page. That made rewording easier because we didn’t have to retype whole stories. While composing the tale that I’d just finished, I’d thrown all of my discarded paragraphs into a pile. After turning in my draft, I separated and counted them. The results stunned me.

“I found out that I rewrote some of my graphs twenty times,” I boasted to Gary Cartwright. He frowned from across the Raw Deal table and said words to the effect of, “Son, Tom Wolfe says that he rewrites some of his one hundred times.”

I, of course, had never dreamed of comparing myself to anyone of such stature, but on that day, thanks to Cartwright, I realized that a Tom Wolfe I would never be.

After freelancing for Texas Monthly from 1977 to 1981, Reavis became a staff writer until 1990. He is retired, living in Dallas.

Gary would be talking on the telephone to novelist and screenwriter Bud Shrake, Ann Richards or Willie Nelson and I’d hear a noise like a mule’s bay – heehaw heehaw. It was like living next door to the Happy Buddha.

Jan Jarboe Russell—

Not long after I joined the staff of Texas Monthly, in 1985, my office was located next to that of Gary Cartwright, who was funny and imaginative, a writer with a cosmic sensibility that was powerful and palpable. I was awed by the bigness of Gary’s rough-and-tumble life.

In the beginning, I put an ear to the wall and listened for signs of his existence next door. Gary would be talking on the telephone to novelist and screenwriter Bud Shrake, Ann Richards, or Willie Nelson, and I’d hear a noise like a mule’s bay: heehaw heehaw. It was like living next door to the Happy Buddha.

I was reluctant to talk to Gary because he was a mythic Dallas sportswriter and I knew nothing about sports. Gary told me it wasn’t the sport that attracted him but the story. I could get behind that. What I wanted to know about were about his interviews with Candy Barr, a Dallas stripper who shot her second husband and hung around with the notorious Jack Ruby.

What was she like? I asked. “Close your eyes,” said Gary. “Now try to imagine a hurricane in a Dixie cup. That was Candy.” No one but Gary said or wrote things like that. He made literature in Texas come alive.

Later we talked about serious things. When my mother died and I was getting a divorce in the early nineties, Gary told me that there was nothing shameful about being heartbroken and reminded me that the lives of Texas women have never been easy. “Hold your head up and this suffering will pass,” said Gary. “If all else fails, sing ‘Up Against The Wall, Redneck Mother.’”

Jan Jarboe Russell, a contributing editor, is a writer living in San Antonio.

Joe Nick Patoski—

I went to say adiós to Gary today. But I really went to tell him, as he once told me, that it’s a Doggy Dog world. Long ago, he related the tale of a football coach he’d grown up under, who’d always try and rouse his team by telling them “It’s a Doggy Dog world!” Evidently, no one ever had the nerve to tell the coach that what he meant to say was “It’s a dog-eat-dog world.” The coach never got it right, Gary never got it right, and neither did I. It really is a Doggy Dog world. I’m just glad I got to share a little bit of it with Gary Cartwright.

Patoski freelanced for Texas Monthly beginning in 1975 and was a staff writer from 1985 until 2003. He is currently writing an alt-cultural history of Austin for University of Texas Press.

Anne Dingus—

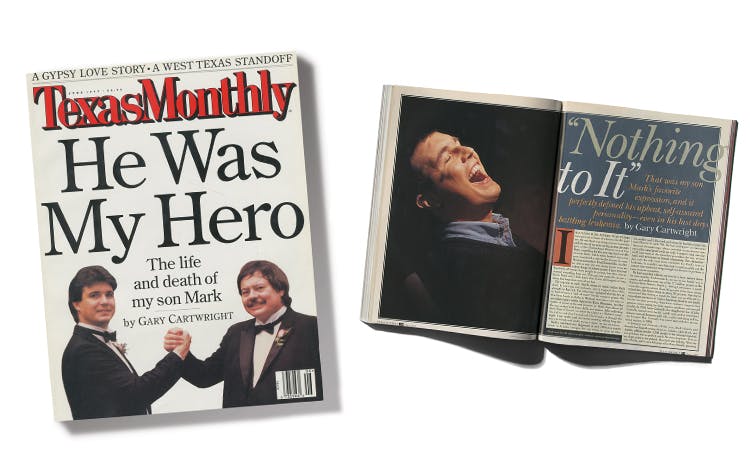

In 1996, Gary’s son Mark received a diagnosis of leukemia. He needed a bone marrow transplant, and Gary arranged a donation day at the Austin blood center in hopes of finding a match. Nearly everyone on the Texas Monthly staff turned up to give blood—and so did hundreds of other people. The waiting room was packed, as was the lawn. Not that many of us knew Mark personally—we were all there for Gary, who stayed the entire day and thanked every person at least once.

But a match was never found. The following year, Mark died. His service at University Presbyterian was even more crowded. The music and prayers were beautiful—and then Gary read a tribute he had written. It was heartfelt and rueful and funny, and that did it—we all started bawling unashamedly. Tissues were passed up and down the pews, and sleeves and lapels did clean-up work too. But Gary’s voice was strong and he never broke down. It was clear that he had long thought about how to bid his child farewell.

When I lost a son ten years later, he took the time to write me a letter about love, loss, grief, and memories.

Thank you for everything, Gary, and goodbye.

Dingus was a staff writer at Texas Monthly from 1978-1983 and 1988-2005. She is retired, living in Austin.

Skip Hollandsworth—

In 1977, when I was in college at Texas Christian University, majoring in English, pondering a future as a professor of literature at some community college in a backwater Texas town, I read Gary’s Texas Monthly article about Cullen Davis, the wealthy Fort Worth oilman who had been arrested for shooting his ex-wife Priscilla; her daughter Andrea; and Priscilla’s boyfriend, Stan Farr. “It was like a fairytale, only in reverse,” Gary wrote about Priscilla, who had been shot in the chest at the Davis mansion. “Rich little poor girl, a prisoner in her own castle.”

“So that’s what good writing is all about,” I thought, sitting in my dorm room, Shakespeare plays and Tolstoy novels stacked on my desk. Although I was just nineteen years old, I vowed that I too would one day write for Texas Monthly. When I was finally hired in 1989 at the age of 31, what did I do? I submitted articles that were nothing more than pale imitations of what Gary already had written. I wrote dozens of true crime stories in which I stole his best lines. I even chose subjects he had already written about. In 1976, he published a famous story about Candy Barr, the infamous Dallas burlesque dancer of the fifties. I hunted her down 25 years later so that I too could write about her. In 1975, he wrote about pit bull dog fighters in Texas. I wrote about them in 2009. And yes, I did an interview with Cullen Davis, asking him in best Cartwright snarl, “Come on now, you did it, didn’t you?” Today, I’m still imitating. In the upcoming April 2017 issue, I have written about outlaw bikers who got into a vicious gun battle in Waco. Re-reading it, I just shake my head. God, I say to myself, just think what Gary would have done with this story. Just think.

Hollandsworth has been a staff writer at Texas Monthly for 27 years.

John Spong—

When I first interned at Texas Monthly in the fall of 1993, my primary duty was tending to Joe Nick Patoski, which mostly meant driving him around while he reported on stories. We logged long hours down on the border, crisscrossing into Mexico, sitting in cafes and bars on both sides and talking to anybody who’d sit with us. That’s how Joe Nick worked. But we had a lot of downtime, and I used that to ask about the magazine. One of the first questions was, “Who’s that old guy with the office just off the edit department? He doesn’t seem to talk to anybody but Greg [Curtis] and Evan [Smith].”

“That’s the Old Man,” Joe Nick said, solemnly. “Jap Cartwright. He’s one of the best magazine writers who ever lived, probably the main reason the magazine exists. You should think of Texas Monthly as ‘The House that Jap Built.’”

I didn’t fully get what he meant until a year or so later. My internship was long over, but somehow my roommate at the time, David Courtney, had finagled his way into my old spot as Joe Nick’s boy. There was an event at Texas State University in San Marcos, a dedication ceremony marking Texas Monthly’s donation of its archive—all the old story files, reporter’s notes, photography and ephemera—to the Wittliff Collections. The night featured a cocktail party followed by readings by writers. David took me as his date.

Not that anybody noticed us, but we were the two dumb kids with six glasses of free white wine apiece stored under our seats when the readings began. Mimi Swartz read from her story on the cheerleader murder plot. Skip Hollandsworth read from his ode to big hair. Joe Nick read from his open letter to Nolan Ryan. Cartwright closed the show with excerpts from “Candy.”

He looked a little crazed as he approached the podium, one eye at a mean slant and the other slightly bugged. When he got to the mic, we could hear him breathe through his teeth. Then came the voice we’d never heard before, an airy growl that punctuated every sentence with a strong stamp of North Texas. He opened with the lede.

On the road home to Brownwood in her green ’74 Cadillac with the custom upholstery and the CB radio, clutching a pawn ticket for her $3000 mink, Candy Barr thought about biscuits. Biscuits made her think of fried chicken, which in turn suggested potato salad and corn.

That word. “Corn.” Coming out of Cartwright’s mouth it rhymed with “barn” and stretched out for a three-Mississippi count. Both our jaws dropped wide. Cartwright continued.

For as long as she could remember, in times of crisis and stress, Candy Barr always thought of groceries. It was a miracle she didn’t look like a platinum pumpkin, but she didn’t: even at 41, she still looked like a movie star.

Ten minutes later he was done, and the room broke into a suitable roar. But David and I were dumbstruck. We stared at each other for a second, then at Cartwright, then back at each other. One of us—more likely both of us—gasped, “What the hell was that?” We then spent the rest of the night figuring out just what that had been. It was what we wanted to do with our lives: Write like Gary Cartwright for Texas Monthly.

Read senior editor John Spong’s remembrance here.

Michael Hall—

Gary was passionate about many things: the Dallas Cowboys, his third wife, Phyllis, his friends. Holding a glass of red wine in one hand and a joint in the other. Telling stories and cracking wise.

Gary was also passionate about injustices. Over his long career, he did several stories about people who he felt had been wrongly convicted and helped get a few of them out of prison. The most famous was Randall Dale Adams, who Gary wrote about in 1987 and who—after the film The Thin Blue Line came out a year later—was released from prison after twelve years. Gary also did several stories on Greg Ott, who had shot and killed a Texas Ranger in 1978—in a tragic accident, Gary believed. He was proud of his role in getting Ott paroled in 2004, later writing, “Nothing in my career as a writer-journalist has given me more satisfaction.”

I learned a lot from Gary’s stories—and his passion. One big lesson was that I could be passionate about a story but even-handed in how I write it. Tell the whole story and let the reader decide what happened: who’s the villain, who’s the hero. One of my favorite stories of of Gary’s was “The Innocent and the Damned,” published in Texas Monthly in 1994. It was about the case of Dan and Fran Keller, a middle-aged married couple who had been convicted in 1992 of sexually abusing children at a day care center they ran in Oak Hill, south of Austin. Both Dan and Fran got 48 years. The convictions were based in large part on allegations made by three kids that bordered on the hallucinatory: that the Kellers defecated and urinated in their hair, put spells on them, baptized them in blood in a backyard pool, made them sacrifice babies—one of whom they cut open so they could drink its blood and hold its beating heart in their hands. The kids claimed the Kellers flew them to Mexico and made them dig up graves in Oak Hill. It sounded like the plot of a sick B movie, and by the end of Gary’s reporting, he was certain that no crime had ever happened and the Kellers were innocent.

But when he laid out their nightmare, he laid out both sides—after all, the parents, police, and prosecutors must have known something—and let the reader decide. He did a masterful job, and by the end, it was obvious (to me, at least) that the Kellers were innocent.

It wasn’t so obvious to the police, prosecutors, and judges, and the Kellers stayed in prison for the next nineteen years. On November 26, 2013, I got a call from Fran’s lawyer, with some surprising news: they were getting released and she was going to be transferred back to Austin. On my way over to the jail, I called Gary, who lived nearby, and told him about it.

Gary was amazed that it was finally happening, and he said he’d like to be there to see this. He was 79 and had a lot of time on his hands. He’d recently had heart surgery, plus his fourth wife, Tam, had just died of cancer. His active journalism career was long over and he was working on his memoirs, using his magazine stories and books as a guide, and most mornings he’d wake up and lie in bed, remembering—for two or three hours. Then he’d get up and write. Here was a chance to actually see one of those memories in the flesh.

Gary’s girlfriend, Jane, dropped him off thirty minutes later and we walked slowly to the lawyer’s office—he was obviously still recuperating from the surgery. “I never had any doubt about Dan and Fran’s innocence,” he told me. “I couldn’t believe others didn’t see what I saw. It was like a witch hunt.” He had stayed in touch with them for a while, writing letters and even visiting, but hadn’t heard from either in years.

We walked in and met some of the others waiting for Fran to get out. A middle-aged woman approached Gary with tears in her eyes. It was Donna Bankston, Dan and Fran’s daughter, and she stopped and reached out and put her hand on his shoulder. “Thank you so much,” she said, and began crying, then wrapped her arms around him.

Gary, who was always so scrappy and sarcastic, was overwhelmed by her gratitude, and he hugged Bankston back, reveling in the moment. He wouldn’t get to see Fran that day—jail officials released her hours later, hustled out a side door—but it was clear that this was enough. It was another immensely satisfying ending to a story he’d done long ago, and a sweet, fitting coda to his career.

Hall, a staff writer, has been with the magazine since 1997.

Pamela Colloff—

I always wanted to know Gary’s secret. Over the years, I tried wheedling it out of him. Many of us did, in conversations at the office (when he happened to stop by); at bars; at our annual holiday party; or wherever we could corner him. We never asked him about it directly. Instead, we danced around it, asking about the technicalities of reporting and writing. But what we really wanted to know was this: How do you do what you do? We all wanted to write like him. We all wanted to know his secret.

Most magazine writers love this sort of attention. After all, we spend most of our time alone, staring at a computer screen, consumed by anxiety and a fear of failure. But Gary hated adulation. He would squirm in his seat when any of us at the magazine—many of whom were three and four decades younger than him—were too appreciative. He deflected our questions with what seemed to be a sincere appreciation for our writing, and inquiries about what we were working on. I always walked away impressed by his generosity, but disappointed that I’d failed to extract any trade secrets.

Many years ago, a number of us decided to throw a dinner party for Gary. We had it at Helen Thorpe’s place, because she was the only of us at the time who owned a house and a matching set of plates (not that Gary could have cared less). Much of the evening is a blur because Gary was so deeply uncomfortable with the set-up—a dozen expectant, young faces staring at him, down a long table, eager to talk journalism—that he eventually pulled out a joint. As he passed it around, he told us, perhaps apocryphally, that it was “Willie weed.” Whatever it was, it was fearsomely potent.

Before the evening devolved—there was more Willie weed, and some regrettable dancing in Helen’s back yard—I remember slipping in a question about writing. “When does it get easier?” I asked.

I remember Gary laughing in the big, expansive way that he did. “It doesn’t,” he said. “If anything, writing gets harder, because the expectations you set for yourself keep getting higher.” He looked down the table at me and smiled. “If it ever gets easier,” he said, “then you know it’s time to hang it up.”

Colloff has been a staff writer since 1997.

But what we really wanted to know was this: How do you do what you do? We all wanted to write like him. We all wanted to know his secret.

David Moorman—

Legendary. Inimitable. Completely unforgettable. Gary Cartwright was big-hearted. That was the first thing. But he also had a wry sense of humor. And at times he appeared to be considerably larger than life. Legendary. Inimitable. Completely unforgettable.

Moorman was a fact-checker from 1975-1984 and 1987-2016. He writes fiction in Austin.

Patricia Sharpe—

Gary Cartwright was half Johnny Cash, half Dylan Thomas. The Johnny Cash side was hard-living and more than a little wild—genteel people like me only heard the G-rated stories, like Gary dressing up as a waiter and taking a flying leap off the diving board into a country club swimming pool in Fort Worth. That side loved the night life and the people who lived in the shadows. He could talk to anyone—college professors, convenience store clerks, prostitutes, murderers, teenagers. They all opened up to him. That’s why he was a fantastic reporter.

The Dylan Thomas side of Gary savored the glory and absurdity of life and wrote with an uncanny blend of lyricism and humor. One of my favorite stories is his tale of an ill-fated camping trip with some enormously annoying city people. At the end of every ridiculous turn, he plaintively asks: “Are we having fun yet?” Finally, the day winds down, the bickering stops, and he has a moment alone. Gazing into the blackness of the West Texas night, he is suddenly humbled and awestruck: “Are we having fun yet? Overhead, a million stars laughed.”

After starting as an editorial assistant in 1974, Sharpe is now an executive editor in charge of food and restaurant coverage.

Katy Vine—

I have read his stories. I have outlined them. I have studied his sentences and to tried to figure out what makes them growl, though I came away scratching my head: it was just Gary.

When staff writers were asked to name a favorite Gary Cartwright story three years ago, in celebration of his eightieth birthday, I wrote that his 1975 article about pit bull fighting, “Leroy’s Revenge,” “has got to be one of the most disgusting, riveting stories we’ve ever published. It’s not a story you put down and pick up again, although it might be a story you throw across the room and pick up again.” Thinking back on the way Cartwright could use shock for laughs, I think this description sometimes fit Cartwright himself.

But his big personality only drew fans—and the staff—closer to him, and, upon closer inspection, one often found a kind and generous person. One night in 1997, Cartwright hosted a legendary dinner party for the younger writers in Austin. He relayed long, winding tales about busting the El Paso “private investigator” Jay J. Armes. He talked about black mollies and Outlaw Country. He offered a sort of Luddite’s Guide to Creating in a Digital Age, recommending we begin each draft of a story with a blank document (as one would on a typewriter) rather than tinkering with existing text and editing ad infinitum. He urged us to view each article to work as literature, dammit, putting fear in our hearts that he would be watching and judging. How lucky we were to have such a critic.

Vine is a staff writer. She has been with the magazine since 1997.

Michael R. Levy—

I knew that to be successful, Texas Monthly had to be first and foremost a magazine for writers. So in the year before the first issue appeared—February 1973—I sought out Gary Cartwright for his wisdom. In college I had read Gary’s work in Harper’s, back when the editor there was Willie Morris, and the only way to describe his impact was that I was mesmerized. Gary, Bud Shrake, and Dan Jenkins had been trained under sports editor Blackie Sherrod at the Fort Worth Press, where Blackie taught them the craft of journalism—a journalism based on telling stories in a way that held a reader’s attention and offered a true understanding of events. Sitting in Gary’s living room, I could only stutter and stammer, but when he starting writing for Texas Monthly, I knew we were going to make it.

Gary gave our readers remarkable stories, and he taught our other writers by example, making them better than they ever thought they could be. He set the standard required to be a Texas Monthly writer; with Gary, the entire staff saw what was necessary to do this right. Gary’s core talents were ones that every journalist must have, and very few do. He worked hard to get the facts, and to get subjects to trust him enough to tell him what he needed to know. Then after gathering ever so many details, he sifted through them and, with his wisdom and common sense, figured out what they all really meant. He used his great gift with words to tell a story in a way that our readers were mesmerized too. Gary was a gift giver: every reader finished a Gary Cartwright story with a much better understanding of the human condition.

Damn. I really wish Gary could give us just one more story.

Michael R. Levy is the founder and publisher of Texas Monthly. He was at the magazine from 1972 to 2008.

Texas Monthly cover images by Claire Hogan.

- More About:

- Gary Cartwright

Brian D. Sweany—

Brian D. Sweany— Jan Reid—

Jan Reid—