“In the year of our Lord, 1891, I became pregnant with an idea. Being at the time chief editorial writer on the Houston Post, I felt dreadfully mortified, as nothing of the kind had ever before occurred in that eminently moral establishment. Feeling that I was forever disqualified for the place by this untoward incident, I resigned and took sanctuary in the village of Austin. As swaddling clothes for the expected infant, I established the Iconoclast, which naturally gravitated to Waco, the political ganglion and religious storm centre of the state.”

Thus did William Cowper Brann, the most controversial and widely read Texan of his day, write of the founding of the Iconoclast, a journal that by the end of 1894, its first year of publication, had a circulation of 100,000. To call Brann a polemicist is akin to calling a jalapeño hot. Either completely for or completely against, he held no middle ground. Political boss Mark Hanna was “the Avatar of Greed, the Scourge of God.” The United States Senate was an “asylum for senility.” But what readers relished most was the Iconoclast’s running war with Waco, Baylor, and the Baptists.

To Brann that countrified Trinity exemplified Victorian hypocrisy in its most splendid combination. When local preachers thundered against prizefighting, Brann wrote, “If Corbett and Fitzsimmons were to fight in Dallas today—without admission fee—Waco, the religious hub of the world, would be depopulated. Half the preachers of Texas would go early to secure front seats.” From issue one, Brann was on the attack. Religious leader T. DeWitt Talmadge was one of the first victims of Brann’s corrosive satire: “The man who can find intellectual food in Talmadge’s sermons could acquire a case of delirium tremens by drinking the froth out of a pop bottle.” Not surprisingly, Talmadge christened Brann “Apostle of the Devil.” The name stuck, and Baptists began to pray for deliverance from that journalistic scourge.

Brann, who half seriously believed that the only thing wrong with Baptists was that they weren’t held underwater long enough, never let up. No Iconoclast was without an exposé of some religious quackery or foolishness that Brann would righteously flay. Then Antonia Teixeira came along. She became to Brann what Helen became to Troy: the cause of an epic disaster.

A Brazilian missionary student at Baylor, Antonia boarded with Baylor’s president, the Reverend Dr. Rufus C. Burleson. While there, she became pregnant. In the summer of 1895 H. Steen Morris, a relative of Burleson’s, was arrested and charged with her rape. Brann put two and two together, and it came up “Baptists and a despoiled innocent.” He could ask for no better cause.

Baylor, Brann wrote, would “stink forever in the nostrils of Christendom—it is damned to everlasting fame.” It was as if the university itself had committed the rape. Baptists and Baylorites tried to defend their honor while Brann exploited the issue for two years. He was selling papers.

He was also raising hackles. It was only a matter of time before Baylor sympathizers would act. When Brann proposed the erection of a monument commemorating Baylor’s taking “an ignorant little Catholic as raw material” and getting “two Baptists as the finished product,” Baylor loyalists figured they had had enough.

On a Saturday afternoon in October 1897, Brann was abducted at gunpoint and driven to the Baylor campus for a lesson in humility. Beaten and threatened with worse, he was chased off campus. A week later he was caned and horsewhipped by a father-and-son team of Baylor partisans. Brann began to carry a gun and took shooting lessons. Six months later he got his chance.

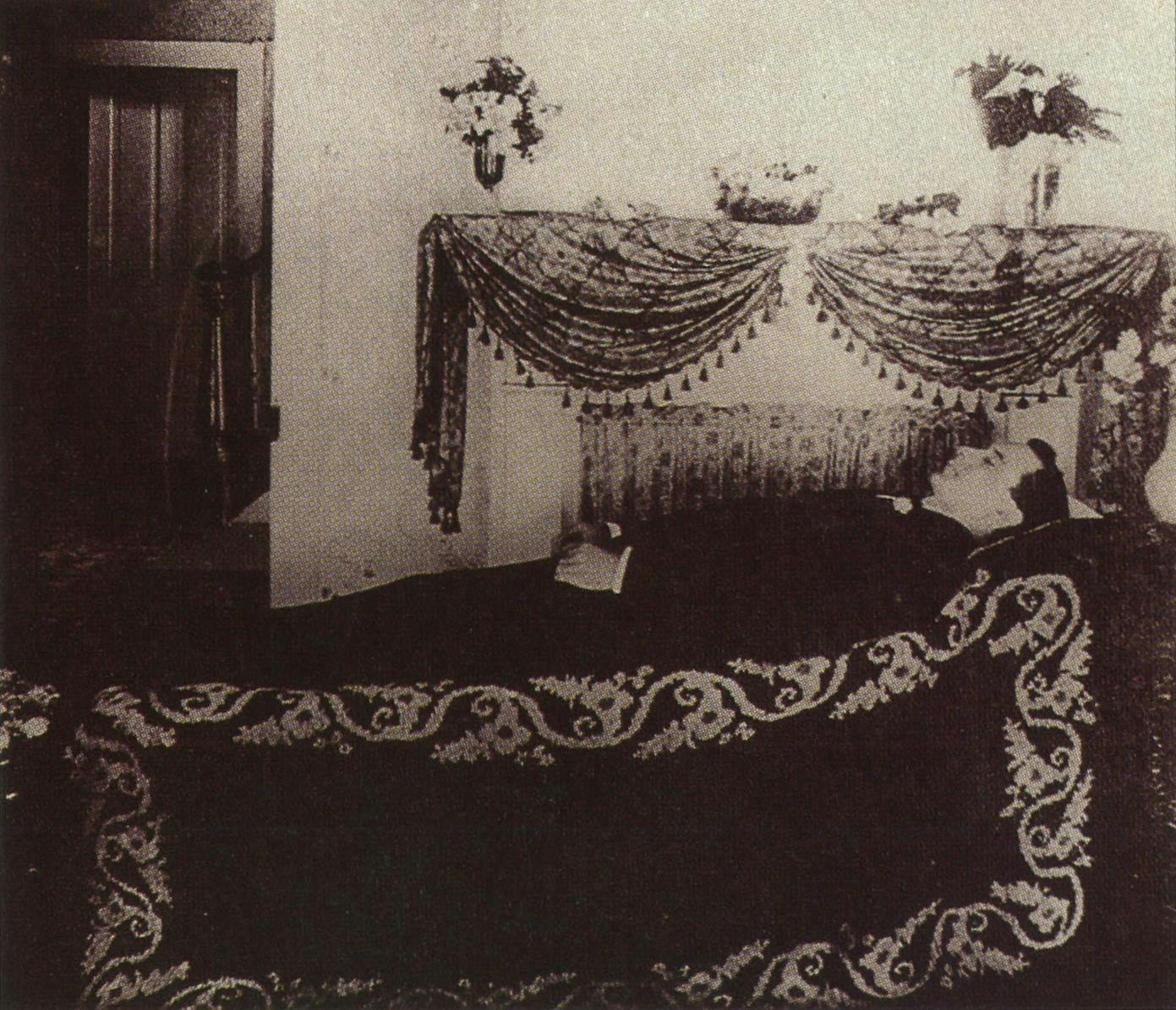

Brann was to take a well-earned vacation in the spring of 1898. He and his business manager were downtown buying railroad tickets when from behind them stepped Tom Davis, a local real estate investor and vocal detractor of Brann. Davis drew his pistol and shot at the lanky editor. Brann whirled, returning fire. The two emptied their six-shooters into each other as the late afternoon crowd stampeded. Moments later Davis was lying in a pool of blood, and Brann—shot in the groin, foot, and back—slid to the ground. He died early the next morning. Davis, hit six times, died soon after Brann. No one has given Texas Baptists much trouble since.

- More About:

- Texas History

- Baptists

- Waco