This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

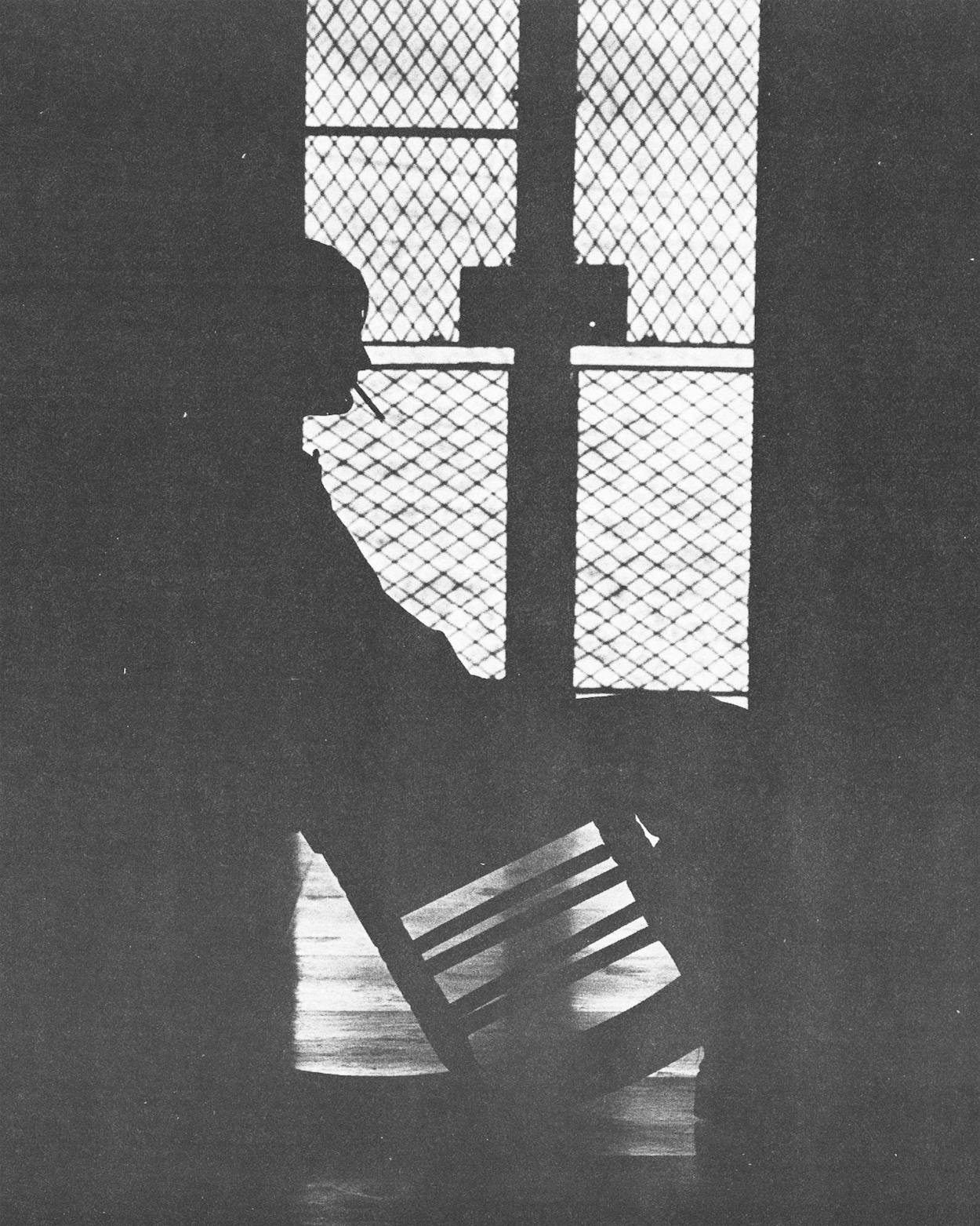

Two tall chain-link fences topped by concertina wire set off the dormitories for the criminally insane from the rest of Rusk State Hospital. To get inside this fortress in a forsaken corner of the Piney Woods, you have to go through gates operated by remote control from guard towers and pass half a dozen bored, blue-uniformed security men who lounge in folding chairs at the main entrance, staring hard at all who enter. I have no difficulty getting past them because my nametag identifies me as an attendant, or, in the institutional parlance, a Psychiatric Security Technician—a PST.

Getting the job was easy. Turnover is high, 60 per cent annually among the 137 PSTs. On the day I applied, there were 15 openings. I lied about my identity, presenting the Social Security card of another man, along with an educational and employment record I had simply dreamed up. I listed the street address of a motel as my home and claimed that my previous employer was a man who had recently moved out of the region. No one cared to investigate. Rusk State Hospital pays PSTs $610 a month, so it has to hire whoever it can get. Few men in their prime will go to work here, and, understandably, few women want to work in the Maximum Security Unit, because most of its three hundred or so inhabitants are males, either felons or accused men sent for pretrial examination.

Some are timid and confused. Their connections with reality are fragile, they do not understand what criminality is, and their most serious offenses may have been stealing hymnals from chapels or writing checks in Clark Kent’s name. Any violent urges they may have are numbed by drug therapy. Others, those whom the psychologists call sociopaths, are habitually drawn to violence and deceit. These men, as often as not, see Rusk as a gambit for avoiding prison. At the hospital, they continue to defy control, committing crimes—usually assault on other prisoners—while there.

The Maximum Security Unit at Rusk is different from other mental-care facilities because it houses some men who ought to be in prison, and it is different from other penal institutions because it houses some men who are fairly harmless and only in need of psychiatric care. This dual function is the source of most of the problems in the unit.

The dorm where I work, Skyview II, like the three other Maximum Security wards, locks with keys that only attendants carry. Heavy metal screens cover all the windows. Otherwise, the four Skyview units resemble one-story college dorms. They are the newest—less than five years old—and the most comfortable buildings at Rusk. Each contains four residence wings, with four rooms on each wing; patients sleep six to a room in conditions similar to those you’d find in the enlisted men’s quarters on a military base. In Skyview II, one wing is vacant now, one is populated by male patients under 21, one is reserved for adult drug addicts, and the fourth is for newly admitted adult males. In addition to residence wings, each of the four Skyview units contains a cafeteria, a laundry room, a recreation center, administrative offices, a pharmacy, and a nursing station.

The other attendants on my shift—except Billy Handsome—are already congregated at the nursing station when I come in about fifteen minutes late, as usual. Being late is not a concern here; the atmosphere is lax. Billy Handsome, a thirty-year-old, long-haired bachelor, spent last night at a rock concert in Dallas, and he has already gone to the drug-abuse ward to sleep off his hangover. The others—Big Boy, John Henry, and our foreman, Slim—all got here before starting time because none slept well. They were called back to work in the middle of the night because of a bomb threat. Even though they had to work when I didn’t, nobody begrudges my absence. Because the state does not pay for overtime, dodging it is an accepted practice. “You’re lucky you don’t have a phone, that’s what,” Slim says good-naturedly.

There is camaraderie among the attendants—not because the work is hectic and dangerous, but because it usually isn’t. Were it not for companionship (and an occasional fistfight among the patients) our routine would be unbearably dull. On morning shifts, we PSTs wake up our charges, watch them take medication, serve breakfast, and wait for lunch. After lunch we wait for 2 p.m., quitting time. When we are on the evening shift we wait for supper and afterward lock the patients into residence wings for the night. Then we wait for 10 p.m., when we can check out and go home. Men on the night crew do little more than baby-sit. They pass their time gossiping, watching television, and playing Foosball. A PST who does not enjoy those pursuits will not be popular with his co-workers, nor will he want to stay on the job, for there is little else to do. The patients, for their part, are as bored as we are.

This morning it is John Henry who tells the patients to wake up, speaking over the intercom. I set the shaving mugs and razors with locking blades on a counter just outside the door of the nursing station. Big Boy goes to the intercom to give the cigarette call and, when the patients come to him, tosses each one a white package of harsh cigarettes, actually little cigars, with the letters RSH printed on the wrappers. Then sunburned, white-suited Nurse Johnny comes out of his office, where he has been sorting and counting pills, to call patients to the “pill line.” Within a few minutes, about half the fifty men on our dorm are queued up in front of him, ready for their morning doses. Some are dressed in brightly colored Western shirts and gray or light-blue pants, clothes which the hospital dispenses. Most of them are unkempt, especially the younger patients, many of whom do not shave. If there is a characteristic common to the disturbed inmates, it is their posture. The men in line slump, lean to one side, hang their hands low, or turn their torsos nearly sideways.

Standing in the hallway beside the water fountain are two young men from the adolescent ward, Roy and Ruben, both twenty. Roy is wearing blue Levi’s and yellow-embroidered boots sent by his sentimental parents, who believe he is innocent of the rape he boasts about. Ruben, who looks like Sal Mineo, has a towel curled around his neck, its ends drooping down onto his white T-shirt. His orange pointed-toe shoes have been shined to a high gloss. Both youths are classified in the records as sociopaths, and both are here for having committed crimes involving carnal desire. Roy is a rapist; Ruben was a homosexual prostitute who one night quarreled with and then stabbed two of his clients. Neither of them has been prescribed any medication: although hallucinations can be suppressed by drugs, a propensity to crime cannot. So they come to the pill line every morning to extort, barter, or beg drugs from patients who have a legitimate need for them.

The most visible patient in the dorm, and the one most despised by the others, is El General, who has not shown up for the pill line. El General, who speaks only Spanish, is a hulking 21-year-old who is severely retarded and epileptic. He has spent most of his life in institutions without learning much. Sometimes El General defecates in bathtubs and sometimes he urinates in water fountains. He is usually the most amiable man on the ward, but, if angered, he is difficult to subdue. El General is here because he struck out at patients who harassed him at another hospital.

“Police power at Rusk has shifted from the attendants to sociopathic inmates, who spend most of their time looking for opportunities to maul other patients.”

Like the other patients, he has been assigned a sleeping bunk and a locker for his belongings. But El General does not understand what property and place are—he can’t even remember where he slept the night, or the hour, before. Like a street urchin, home for him is wherever he happens to be when drowsiness overtakes him. John Henry and I find him asleep on an unassigned bed in the adolescent wing. There are no sheets on the plastic mattress, but that is unremarkable; sheets are one of the comforts for which El General has no appreciation. He is wearing the maroon jeans and suede running shoes that his mother brought him two months ago.

I grab El General by the ankles and shake him, moving his legs like the blades of scissors. He doesn’t budge. I try pushing hard on his ribs, rocking him back and forth, while John Henry, standing behind me with his arms folded, stares down at El General, grinning. I lean over, putting my hands behind El General’s shoulder blades, and strain to raise him. With some difficulty I lift his torso about six inches above the bed and let him fall back. He doesn’t blink. John Henry chuckles in a high-pitched, feminine tone, which seems wildly incongruous with his colossal physique, but he offers no help, so I raise El General’s torso again, letting him fall back on the bed again, and again I get no result.

It is obvious that my methods won’t awaken El General. So John Henry leans across the bed and gently backhands El General across the cheek. El General stirs. John Henry slaps him again, and this time El General opens his eyes.

“Why are you hitting me? Why are you hitting me?” he says in Spanish, scrambling out of the bed.

“Let’s go. It’s pill time,” he tells El General, who thinks he is about to be hit again. He dodges past the attendant and ducks behind a locker, hoping we will not notice him there. John Henry approaches the locker like a wrestler coming out of his corner. El General sees him and turns his face the other way, toward the wall.

“No, no me vas a pegar,” El General wails, stiffening his body.

I tell El General that we are not going to hit him. John Henry, resigned for the moment to the idea of persuading El General, does his best with the Spanish he has picked up on the ward.

“Medicina, General, medicina.”

El General is too frightened to believe it, and we know why. Last night, according to the night log the attendants keep, several other patients, including Ruben, Roy, and another sociopath, Killer Duke, attacked El General. That is how they have fun. While they were chasing him around the wing, El General went into a seizure. He fell, or was knocked, against a Sheetrock wall panel, in which there is now an indentation stained with his blood. Several strands of hair protrude from the crack made by his head. The night crew, as always, found out about the incident too late to stop it, and El General was already having his seizure when they arrived on the scene. El General can’t understand that John Henry and I are attendants, not patients, or that there are rules against brutality. We are, in his mind, just two nameless men—I doubt he remembers seeing us yesterday or the day before—and our apparent intentions are violent.

John Henry throws a wrestling hold around El General’s neck and pulls him away from the locker. Then he stretches out the patient’s right arm, holding it stiff while encircling El General’s face with his other arm. With El General thus under rein, John Henry marches him down the hallway, toward the pill line.

“Medicina, medicina,” he tells El General.

“Me-di-ci-na. Me-di-ci-na. Me-di-cina,” El General chants over and over. El General often repeats what we tell him, not because he is sarcastic but because he is afflicted with echolalia, a disorder characterized by a fascination with sounds. At the nursing station El General realizes what is going on and relaxes. John Henry lets him go. Like the others, El General takes his place in line.

Most people in mental hospitals have come there by voluntary or civil commitment. Either they have asked to be let into a mental hospital—a common enough request, made especially by alcoholics in need of drying out—or their families have gone to court alleging that Uncle Ted or Brother Joe is behaving strangely and have gotten commitment orders from a judge. The presumption in both kinds of cases is that the person committed is helpless, because he or she does not firmly grasp reality, and harmless, because he or she has committed no crime. Patients who voluntarily commit themselves may walk out at will; those who are committed in civil proceedings may leave when review boards deem that they have been sufficiently treated or restored to sanity.

No one, however, may commit himself to the Maximum Security Unit, nor can anyone walk away from it when he wants to. No one may be brought in until accused of a crime. Patients are brought to the MSU, often in shackles and waistcuffs, from three sources: other mental hospitals, prisons, and courts.

The crimes that MSU inmates have committed range from breaking into automobiles to multiple murder. Hippie Fred, a patient in my dorm, was brought here from Austin State Hospital, where one sunny afternoon he jumped the fence and ran away. When hunger overtook him hours later, he entered someone’s house, went to the kitchen, and began preparing a peanut butter and jelly sandwich. The owners of the house called the police, who booked Fred for burglary and returned him to the hospital. From there he was sent to Rusk, where he wanders about looking confused and sheepish.

Patients come directly to Rusk from courtrooms and jails when they have been judged not guilty of crimes by reason of insanity or when their competence to stand trial is in doubt. No one is sentenced to serve time here, though defendants who are either incompetent or insane or both must remain until they are judged able to stand trial.

The distinction between incompetence and insanity is an important one for many of our patients, especially ones like Solomon, a nineteen-year-old black kid sent here for competency training.

Solomon killed his grandmother with a butcher knife one autumn night in Fort Worth nearly two years ago. His court-appointed attorney could not communicate with Solomon and therefore secured a competency examination, held in the office of a psychiatrist. In Solomon’s court dossier, I found a record of that conversation.

Psychiatrist: “What is the function of a district attorney?”

Solomon: “He labors a portion of the kind of success that you do and what you include in. He tells you who the caseworker is. He is for to manage your main subject and verb.”

Psychiatrist: “What is the function of a judge?”

Solomon: “If you was to be eliminated one night, tough to be sustained. Trial with your producers. Like if you was under pressure and any persuasion, it would affect you or be in your midsection.”

Answers like these persuaded a Tarrant County judge that Solomon was incompetent. He was brought to Rusk, where he has been taught better civics. Today, thanks to his competency classes, he knows by rote what a judge and jury are. He now admits that he is a murderer, though he often writes letters home to the grandmother he killed. Because he can parrot the rules of courtroom procedure, a review board has found him competent to stand trial. In a few weeks Solomon could be back in the dock. If his attorney requests a sanity hearing for him and a jury finds him insane, he will be returned to Rusk. With time, therapy, and medication, he may improve. When he is no longer deemed dangerous, he may be transferred to another mental hospital. If he is ever restored to sanity, he may be released without facing trial. Solomon is presently in danger of his competency being taken for sanity when he is returned to Fort Worth. If that happens, he could be convicted of murder and sentenced to Huntsville. A careless or callous defense attorney might even persuade Solomon to plead guilty.

Solomon belongs in the Maximum Security Unit because he is crazy and in all likelihood unwittingly dangerous too. But others here are willfully dangerous and not in the least insane. Often, they were charged with drug abuse—usually heroin addiction—and sent to Rusk for pretrial examination. Roy, the rapist, is one of these people. Six months ago he pulled a black stocking over his head and visited the home of a family friend expressly to rape her (“Because I hated the bitch,” he explained to me). Afterward he fled and made coolheaded attempts to evade identification. Carelessness, not insanity, was his downfall. Caught with incriminating evidence, he pleaded insanity and was sent to Rusk for evaluation. “It’s a lot better doing time here than in the county jail,” he says. In my dorm there are others like him: Ruben, Killer Duke, who murdered his partner in a dope deal, Juanito the armed bandit, and several more.

But to the general public, Rusk State Hospital does not have a pleasant reputation. During the summer of 1977, journalists and investigators from the Texas Department of Mental Health and Mental Retardation, which is supposed to oversee the hospital, swarmed over Rusk, looking for and finding evidence that the attendants were brutal. That autumn, 124 employees were fired, and the Cherokee County attorney filed criminal charges against 14 of them, though none of them was brought to trial. Nevertheless, the revelations and the employee purge were effective. Inside the hospital today, sustained beating of patients is rare. Most attendants now prefer keeping their jobs to hitting unruly or annoying patients, and patients are now told when they come in that if they are struck they have the right to file an abuse complaint. So far this year, sixty of them have. Most of their complaints have been dismissed, but not before a board of MHMR employees and community volunteers has interrogated the parties named in each one.

If the beatings have largely ended, another problem that was discovered—patients beating patients—still exists, and there is statistical evidence that it may have grown worse. During the first seven months of 1978, 190 injuries to patients were recorded in the Maximum Security Unit, compared to 249 in the twelve months before the investigation. That works out to 27 patient injuries a month this year (most of them the result of fistfights), compared to 20 a month last year, and there are only three-fourths as many patients in the Maximum Security Unit today. Attendants blame the increase on the new regulations they operate under, which forbid them to take punitive or deterrent action against brutal patients. Before the 1977 investigations, attendants often locked the bullies in isolation cells. Today those cells may be used only under orders from a Rusk physician, who can prescribe isolation only to keep suicidal or epileptic patients from hurting themselves.

Behavior modification, another means of control, has also been proscribed on the criminal wards. Most psychologists favor it; as one told me, “Let me control cigarettes, coffee, and Cokes, and I’ll control those three hundred patients in ways you wouldn’t believe.” The personnel at Rusk would like to have the power to give or deny amenities. But B-mod, as it is called, has been limited to a small program in Skyview III, the women’s dorm, largely because administrators fear that its wide use might prompt another investigation. The lesson of the 1977 investigation is that patients, unlike prisoners, must be treated with respect; they are presumed to have the same rights as any other citizen. If they are allowed access to telephones and the mails, if they may not be confined, or even forced to bathe, the administration reasons, who is to say that denying them cigarettes is not also infringing on their civil rights?

The result is that police power at Rusk has in some ways shifted from the attendants to those sociopathic patients who are cunning enough to manipulate the others. These patients, who have filled the vacuum left by the attendants, need not fear the courts, which are unlikely to prosecute misdemeanor complaints against them, or the people in authority, especially the attendants. Some have even learned to manipulate the abuse-complaint system. If an attendant strikes him or curses him or even shouts at him, a calculating sociopath will threaten to file an abuse complaint. If the attendant ignores the threat, the patient may actually file the complaint, causing the attendant to come under suspicion. Today on the Maximum Security wards, there are sociopaths who spend most of their time looking for opportunities to maul other patients, and there are attendants who spend most of their time waiting to record the resultant injuries.

The attendants on the dorm this morning tacitly assume that Roy, Ruben, or others of their gang from the adolescent ward will renew last night’s attack on El General. Everyone has seen the pattern before. Normally harmless, El General, after several turns as the victim of harassment, becomes cross, punchy, and unmanageable, a danger to anyone who comes within his reach. After a few days his equanimity returns, and the sociopaths begin another round of taunting him. I am in the nursing station with Slim, waiting for the inevitable, when El General strides up, in a good mood despite last night’s incident.

He walks into the room confidently, as if he worked here; El General is the only patient allowed this privilege, because we know he is too innocent to take advantage of it. I hand him the nearly empty can of Coke I am drinking. El General is a walking disposal; he downs it all in one gulp, then looks around for more food or drink.

“Hey, General, throw that can away,” Slim tells him.

El General opens the drawer of the nursing desk and drops the can in.

“Not in the drawer, you dumb ass. In the wastebasket, General. Over there in the wastebasket,” Slim says, this time pointing at the trash can.

Slowly, El General pulls the can out of the drawer and turns toward Slim, watching for new instructions, unsure what he has been told, and probably afraid someone will hit him.

“Over there, dumb ass,” Slim repeats.

El General turns to the wastebasket, but does not fix his eyes on it.

“En el basurero,” I tell him.

He obeys.

“Say, you must speak that Spanish pretty good. Ask that General how old he is, why don’t you?” says Slim.

El General says he is five. I insist that he is not, but he will not reconsider.

“Yeah, that’s what he always says,” Slim tells me. “He had a real bad fever of something like 104 for three days when he was five, and that burned his brain up, the doctors say.”

I ask El General why he has never mastered English. “Because there are no chocolates,” he tells me. Then he begins to mutter something about a dog, pointing at the glass wall that looks out on the hallway.

“El General, vámonos. Yeah, vamoose. That’s right, get out of here,” Slim says. El General meekly complies, and Slim begins to tell me at great length about the Opelousas catfish he caught yesterday. Fortunately we are interrupted by another patient.

It is Roy, the rapist. He has come to get a light for his cigarette.

“Hey, Roy,” says Slim, “was that lady you raped in Lubbock any good?”

“She sure was.”

“Good enough for thirty years, huh?”

Roy says that even if he’s sentenced to sixty years, he’ll spend the time thinking about the pleasures of the rape.

One of the Maximum Security Unit’s three doctors walks in. Slim introduces me to him—he’s called Doctor Benji and is a native of India somehow transplanted to the Piney Woods.

“Hey, Doc, you ever heard of a woman having a headache for five days?” As usual, Slim is in a teasing mood.

Doctor Benji says he hasn’t.

“I thought not. I don’t know what my old lady is pulling on me, you know? It’s been five days, and she won’t put out. I may have to get Roy here to show me how to get it,” he says, nodding at Roy. The doctor, embarrassed by the conversation, edges off down the hallway toward the administrative office.

I slip out the door, hoping to discover what dark deeds are hatching in the adolescent wing.

Solomon, Killer Dave, Juanito the bandit, and Ruben are slouched in chairs around the television set. A commentator is interviewing Myron Farber, a New York Times reporter who is being sent to jail. The four patients understand nothing that is said. They are watching because they don’t have anything else to do.

When I sit down, Ruben gets up to show me three burns on his right arm, two above and one below his tattoo, a skull and crossbones emblazoned with the legend “Born to Lose.” Ruben burned himself last night with a match, but he says he doesn’t know why. He also set fire to a photograph of his old girl friend from Corpus Christi. I ask him whether he burned the picture because he is now enamored of Clara, a Maximum Security patient to whom he waves every night through the screened glass on the dorm’s south side.

“No, man, it wasn’t her. I don’t want nothing to do with that bitch Clara. She’s a mayatera,” he explains in Spanish.

Mayatera is a word I don’t understand. Juanito tells me that it comes from mayate, a demeaning Chicano term for blacks. A mayatera is a woman who prefers black men to Mexican Americans. Juanito tells me that Clara is indeed a mayatera and that Ruben burned himself because he was high on toothpaste cigarettes. I have never heard of them, so Juanito promises a demonstration. The technique is a relatively new one to him; it was brought here only last week by Killer Dave, who, I suspect, also smuggled in the matches Ruben used to burn himself.

Dave gets up to prepare me a toothpaste cigarette, as Juanito explains the process. New patients on the criminal wards are given a packet of toiletries, which includes a tube of fluoride toothpaste. Killer Dave spreads the paste across a cigarette paper, then blows on it to dry it out. He hands it to me, and I light up.

The cigarette pops, like marijuana, and leaves long, flaky, black ashes that don’t fall off. I inhale deeply and soon feel a high, which I believe is from lack of oxygen. It’s a crude feeling, like the feeling of smoking your first cigarette. The taste is foul and the smoke stings my already abused lungs. I refuse to light up a second of these jailhouse joints, but Juanito, Ruben, and Killer Dave assure me that if I smoked several, I would come to appreciate the high. It’s the fluoride that produced the buzz in my head, Juanito tells me.

Solomon sits staring at the television all the while, rocking back and forth in his chair, transfixed. When I ask him what he did with the knife he used to kill his grandmother, consciousness returns to him. He looks over at me, starts to stutter, then says plainly, “She just swallowed it, I think.” He also tells me that his brothers and sisters did not call the police. “They just came automatically. They always do when something happens.” Without inquiring about who had the matches last night—no one will tell me, I know—I go back to the nursing station.

I mention the matches and the toothpaste cigarettes to Slim, who assures me that there is nothing we can do. “Hell, if it wasn’t that, it would be something else,” he says. “We can’t search them whenever we want, you know. Last week they were smoking tea back there.”

After lunch, I return to the nursing station to prepare the paperwork for Killer Dave’s EEG brain-wave test later in the afternoon. Before I have finished, El General comes to the door, wailing. His head is bowed and he holds his hands over his eyes and nose. I put an arm around his shoulder and with a little prodding get him to show me his face. The bridge of his nose is red and swollen.

“They hit me, they hit me,” he says.

“Who hit you? Which ones did it?”

El General looks at me wistfully, dropping his arms to his sides. “El doctor? Mi papa?”

He has never learned to call anyone by name. Whether he really thinks a doctor or his father hit him, I don’t know; he may believe that all males are included in those two categories—except for his brothers, for he also knows the word hermano.

I do not have to wonder long who his attackers were, for Ruben and Roy are soon standing in the doorway, savoring the scene.

“Why did you guys mess with him? Can’t you pick on somebody who can defend himself, like Dave?”

Grinning mischievously, Ruben tells me that he did not intend to hurt El General. Slim, who has been reading the sports section of a newspaper, casts an irritated glance at Ruben.

“Yeah, you’re sorry, real sorry. Just like you’re sorry you stabbed those two queers in Corpus, aren’t you?”

Ruben takes this as his cue to leave and shamefacedly backs away from the door. He and Roy lean against the outer wall of the hallway, waiting for El General to step outside.

Ruben is upset. He does not like to hear homosexuality mentioned. Though he will argue in self-defense that any form of sexual release in confinement is honorable, he is not proud of his role as the dorm whore. On the outside, before his arrest and transfer to Rusk, he was a homosexual prostitute. He insists that he was well paid. Here, he has several times been found in the showers, or even in his bunk, performing a variety of acts with other patients, none of whom is normally homosexual. Ruben feels ashamed about this because here on the ward his services usually cannot be paid for. One of the indignities he suffers at Rusk is being called queer.

Slim looks up from his newspaper again and glances at El General and me, then at the hallway.

“Don’t worry about El General,” he tells me. “It won’t do you no good. There’s nothing we can do.”

“I’d like to take Ruben and Roy to the laundry room and give them a taste of their own medicine,” I suggest.

“Shit! You know the rules. We can’t even put them in isolation. Patients have all the rights today. Pretty soon, I tell you what: they’re going to be running the ward.”

Slim’s advice doesn’t calm me. “Ruben and Roy, why don’t you get your chicken asses out of here,” I tell them.

They slink off down the hall toward the adolescent wing. When El General quits sobbing, I let him go. He ambles off toward the adolescent wing, where I know Ruben and Roy will waylay him again. I want to follow him, but Slim advises me not to.

I turn back to my paperwork, but before I can finish a single form, Roy comes down the hallway, shuffling toward our door with El General in tow.

“Look at El General. His eyes are rolling back in his head.”

It is true. El General’s eyes are rolling up and down, as if operated by some unseen lever permitting him to take peeks at the top of his skull and the inside of his cheekbones.

“Aw, that ain’t nothing,” Slim says. “The doctors say his medication makes him do that.”

I call Nurse Johnny, who is in his office on the other side of the nursing station. Johnny cranes his head out the door as Roy and I lead El General over.

“Aw, he’s fixing to have his seizure. Just lay him down and let him get it over with,” Johnny advises us.

Roy and I lead El General into one of the ward’s two rarely used isolation rooms, a narrow wood-paneled cubicle with a bed and a door that locks from the outside.

El General, who vaguely understands that he is being put to bed, grabs hold of a blanket and lifts it up. Then he freezes, his hand holding the blanket, his head cast down, his eyes fixed straight ahead, seeing nothing.

Roy shakes him by the shoulder.

“General, General, get in bed.”

El General does not respond.

“¿General, nos escuchas? ¿Puedes escuchar?” I ask.

But he doesn’t hear a thing.

Together, Roy and I force him down on the edge of the bed, then push his torso flat. He is lying on his back, but with his forearms raised, the edge of the blanket still in one fist.

Roy bends El General’s forearms down to his sides and puts a pillow under his head. He passes a hand over El General’s eyes, but El General doesn’t see it. He makes no sound.

We hear a rustling behind us. It is Ruben, come to see the fruit of his bullying.

“Get the hell out of here, you pinche maricón.” I have now raised my voice at Ruben and cursed him as well. That, our regulations say, constitutes patient abuse. Ruben ducks out the door.

A deep growl, like that of a dog about to bite, comes from El General’s half-open mouth. It wanes when he inhales, grows louder when he exhales. For ten minutes, the low roar reassures us that he’s alive.

Roy steps out into the hallway, where Ruben is loitering. They exchange whispers as Roy combs his long, ducktailed hair. When Roy steps back into the room, El General sees something, probably his profile. He sits up in bed, then freezes again. We force him back into a prone position and wait perhaps ten minutes more.

Nurse Johnny is now fidgety. El General’s seizures do not usually last this long. Johnny comes into the isolation cell to take his blood pressure.

He measures twice before pronouncing El General’s pulse and blood pressure normal. Then he picks up his equipment and goes back to the nursing station, where I hear him teasing John Henry.

I go out to ask Slim for permission to stay at El General’s side. John Henry, I suggest, can take my place in accompanying Killer Dave to his EEG session. Slim frowns, even though John Henry readily volunteers. I can tell by his glare that he is wondering whether I will ever be good PST material. It is not part of the macho ethic of psychiatric attendants in East Texas to show pity for the helpless.

After a moment, Slim relents.

“All right, you go stay with your girl friend. John Henry can take Dave down to the infirmary. But I’ll tell you something. This falling in love with the patients won’t cut it.”

“He’ll get over that love business, that’s for sure,” John Henry chimes in. “Just wait till one of these patients lays into him.”

I turn away to rejoin Roy in the vigil at El General’s side. Roy, I know, was undoubtedly in on the beating. But at least he had the humanity to be shocked at its result.

El General does not move for ten more minutes. Then his fingers begin to tremble. Little tremors pass through his feet, causing his shoes to vibrate. This continues for four or five minutes, and then El General sits up.

He still apparently sees nothing. He drops the blanket he has been holding and stands up as if to walk. But he does not move forward. He is frozen again. We lay him down. The tremors resume. Then his body goes still, as if his spirit had departed. I notice that El General has wet his pants. Before long he rises again, this time almost fully conscious. When we move toward him he draws back, thinking, I suppose, that we are going to strike him.

“No tengas miedo, General,” I tell him. “Don’t be afraid.”

He looks at me out of the corner of his eye and bellows—a long, savage, childish laugh. He is happy now, even if he doesn’t know why, or where he is, or who is addressing him.

“El General,” I ask in Spanish, “why did you have that seizure?”

“Because there are no chocolates,” he booms, pleased by the sound of his own voice.

My tension slips away. Almost joyfully, I go into the nursing station to report that El General’s siege of unconsciousness has ended.

“Oh, yeah? Well, that’s fine,” says Slim. “I told you it would happen like that.”

Then he turns to Nurse Billy, who is visiting in the nursing station.

“Hey, Billy Boy,” he says, “I want to take my trotline out tomorrow. You think that creek where you fish is wide enough for a fifty-foot line?”

I slink off to the adolescent ward. Somebody has to make sure El General puts on some clean clothes.

The names of the employees and inmates in this article have been changed.

- More About:

- TM Classics

- Prisons

- Longreads