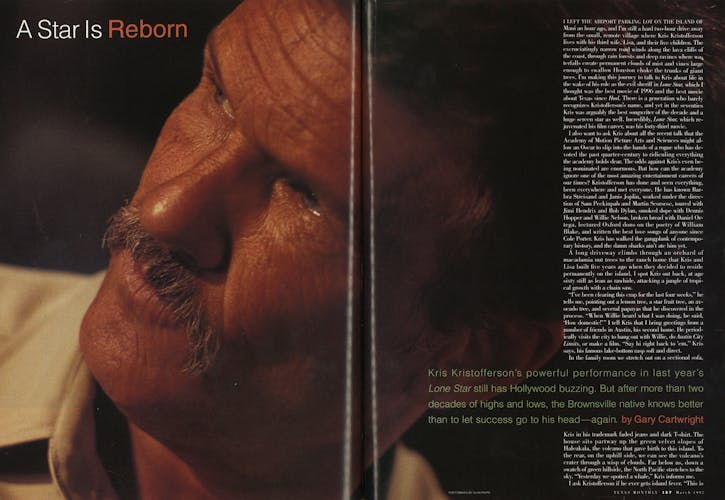

I left the airport parking lot on the island of Maui an hour ago, and I’m still a hard two-hour drive away from the small, remote village where Kris Kristofferson lives with his third wife, Lisa, and their five children. The excruciatingly narrow road winds along the lava cliffs of the coast, through rain forests and deep ravines where waterfalls create permanent clouds of mist and vines large enough to swallow Houston choke the trunks of giant trees. I’m making this journey to talk to Kris about life in the wake of his role as the evil sheriff in Lone Star, which I thought was the best movie of 1996 and the best movie about Texas since Hud. There is a generation who barely recognizes Kristofferson’s name, and yet in the seventies Kris was arguably the best songwriter of the decade and a huge screen star as well. Incredibly, Lone Star, which rejuvenated his film career, was his forty-third movie.

I also want to ask Kris about all the recent talk that the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences might allow an Oscar to slip into the hands of a rogue who has devoted the past quarter-century to ridiculing everything the academy holds dear. The odds against Kris’s even being nominated are enormous. But how can the Academy ignore one of the most amazing entertainment careers of our times? Kristofferson has done and seen everything, been everywhere and met everyone. He has known Barbra Streisand and Janis Joplin, worked under the direction of Sam Peckinpah and Martin Scorsese, toured with Jimi Hendrix and Bob Dylan, smoked dope with Dennis Hopper and Willie Nelson, broken bread with Daniel Ortega, lectured Oxford dons on the poetry of William Blake, and written the best love songs of anyone since Cole Porter. Kris has walked the gangplank of contemporary history, and the damn sharks ain’t ate him yet.

A long driveway climbs through an orchard of macadamia nut trees to the ranch home that Kris and Lisa built five years ago when they decided to reside permanently on the island. I spot Kris out back, at age sixty still as lean as rawhide, attacking a jungle of tropical growth with a chain saw.

“I’ve been clearing this crap for the last four weeks,” he tells me, pointing out a lemon tree, a star fruit tree, an avocado tree, and several papayas that he discovered in the process. “When Willie heard what I was doing, he said, ‘How domestic!’” I tell Kris that I bring greetings from a number of friends in Austin, his second home. He periodically visits the city to hang out with Willie, do Austin City Limits, or make a film. “Say hi right back to ’em,” Kris says, his famous lake-bottom rasp soft and direct.

In the family room we stretch out on a sectional sofa, Kris in his trademark faded jeans and dark T-shirt. The house sits partway up the green velvet slopes of Haleakala, the volcano that gave birth to this island. To the rear, on the uphill side, we can see the volcano’s crater through a wisp of clouds. Far below us, down a swatch of green hillside, the North Pacific stretches to the sky. “Yesterday we spotted a whale,” Kris informs me.

I ask Kristofferson if he ever gets island fever. “This is the best move of my life,” he tells me. “Before this, the happiest place I ever knew was Brownsville, Texas, where I grew up. This is the closest thing to Brownsville, a place where kids can go to school barefoot, where people know when you get sick and tell on you when you’re bad. People here accept us as though we’re part of an extended family. Kids here call me Uncle.”

Then I spring my proposition. It seems clear to me, I tell Kristofferson, that he deserves at last an Oscar nomination for his role in Lone Star, writer-director John Sayles’s magnificent strip-down of the cultures and history of a small town on the Texas-Mexico border. The movie opened to universally good reviews, but as an independent film by a notoriously maverick filmmaker, it was ignored by the Hollywood establishment and, hence, the general viewing public.

Kris thinks on this a while, his deep-set eyes invisible in the weathering of his face. Finally, the eyes flash and sweep across the room like the beam of a lighthouse, and he says, “I’d like to see John Sayles get the recognition he deserves; his message is on the side of the people. The fact that anyone is even talking about my being nominated is so good for my morale it almost doesn’t matter if it happens.”

Kris talks a lot about family and shows me an entire wall covered with photographs. I can see how far he has come. There are pictures of his father and of Lisa’s father, several of Kris as a child and of his eight children from three marriages. He points first to his in-house kids: thirteen-year-old Jesse, twelve-year-old Jody, nine-year-old Johnny (as in Cash), six-year-old Kelly, and two-year-old Blake (after the English poet). Blake isn’t much older than Kristofferson’s first grandchild, who was born last June to his daughter Casey—who was born in 1973 to Kris and his second wife, Rita Coolidge. Two other children, Tracy, who’s 34, and Kris, Jr., who’s 28, came from his first marriage, to his high school sweetheart in San Mateo, California.

“Through the love of my children I’m learning to love adults too,” he tells me, laughing at himself as though he has stumbled across an unexpected truth. The notion of starting over after two failed marriages was daunting. Following his devastatingly bitter divorce from Coolidge in 1979, Kris told an interviewer, “When you get tossed out on the street, you think you don’t have the energy to go through all the unpeeling of layers again to find out who you’re dealing with… The next one will have to be carrying notes from the pope.” Nevertheless he has been married to Lisa for fourteen years, and he tells me, “This has been the best part of my life.”

In one wing of the house he shows me his writing room, guarded by a no-nonsense black-and-white cat named Tuxedo, one of a dozen or so pets in-residence. “I sense that it’s time to get down to business, which means writing,” he says. Like all musicians, Kris used to love the road. The road meant freedom. Now he’s not so sure. The recurring themes in Kristofferson’s work and in his life are loneliness, redemption, home, and the double-edged nature of freedom, and they’re expressed grandly in a line from one of his songs, “The Pilgrim: Chapter 33”: “Never knowing if believing is a blessing or a curse, or if the going up is worth the coming down …”

“You seem haunted by the idea of home,” I tell him. “It crops up in a lot of your songs—trying to find your way back home, judging how far you’ve come from home. Home seems to be a metaphor for something, happiness and contentment, or maybe the Holy Grail.”

“Whatever it is,” Kris says, “it must be something profound in my makeup. When I left the Army, it was like I was running away from home. This place feels like coming home.”

KRISTOFFERSON HAS LIVED AT LEAST THREE LIVES, and I mean lived them. His turning points have resembled train wrecks. He grew up in Brownsville, the son of a career Air Force major general and the grandson of two career military men. There was never any doubt growing up that Kris would be career military. “Kris’s whole life has been those Army white gloves fighting against his jeans,” says a longtime family friend. “You’re a general’s son who likes Hank Williams, where are you?” Kristofferson’s first song, written when he was eleven (just before the family moved to San Mateo), was a Williams knockoff called “I Hate Your Ugly Face.”

People who knew Kris in school remember that there was a sadness about him, a kind of separation. He was brilliant and popular, an acolyte in the Episcopal church, class president of his high school, and a Phi Beta Kappa at Pomona College in California, where he played football, boxed, and was a company commander in ROTC. And yet he seemed to be forever looking for a place with no name, a place he might never find.

After graduation he got a deferment from the Army to accept a prestigious Rhodes scholarship to Oxford University in England. At Oxford Kris wrote a novel, but it was rejected, and he was writing his dissertation on Blake when he decided to leave academic life. He married his high school sweetheart, Fran Beer, and entered the Army with his ROTC commission. He volunteered for every hard job the Army had—flight school, jump school, ranger school. He started drinking. Like everything he did, Kris drank hard. “‘The road of excess leads to the palace of wisdom,’ Blake wrote,” Kris tells me now, smiling at the contradiction at the heart of this perceived truth.

He was a helicopter pilot in Germany for three years before he volunteered for Vietnam. “I was looking for something that would put some meaning in my life, something that was real,” he says. “I didn’t know anything except what I read in Stars and Stripes or got through military channels. I believed we were fighting for freedom over there.” Instead of sending him to Vietnam, the Army assigned him to West Point to teach English. That was 1965, and he was nearly thirty. But Captain Kristofferson’s first life was about to be abducted by aliens.

Before reporting to West Point, he took a leave and visited a friend in Nashville, bringing along tapes of some songs he had written in Germany. Nashville was exciting, intoxicating, potentially lethal. “I was still in uniform the first time I met Johnny Cash,” Kris tells me. “He was backstage at the Grand Ole Opry, dressed all in black and pilled up—electric, dangerous, and unpredictable. And, frankly, it looked very attractive to me!” Kris resigned his commission, moved his wife and two children to Nashville, and got a job at Columbia Records as a janitor. “I accepted that it was a leap of faith, leaving home to do what I loved,” Kris says, “but I knew from the minute I started doing it that I was right.”

Not surprisingly, his marriage collapsed a few years later. Heavily in debt and facing $500 a month in child support, Kris took a job flying helicopters to offshore oil rigs in the Gulf of Mexico. He commuted between Baton Rouge and Nashville, consumed more than ever with making it as a songwriter, but increasingly confused about reality. “A lot of my pilot buddies from the Army were coming back from Vietnam telling horror stories,” he remembers. “Some really good career officers went over there believing in what our country was doing and came back sickened by what they saw—throwing people out of choppers, killing civilians. It wasn’t like a sudden change of mind, but the more I read, the more the scales fell away from my eyes. It was disturbing for a kid who grew up in Brownsville believing that God was on our side and our country stood for justice and freedom.”

Kristofferson’s first recorded song was “Vietnam Blues,” which made fun of anti-war protesters. After that his lyrics turned to the left. Having grown up believing in justice and freedom, he began demanding them. “Nashville was a real Rubicon in my life,” Kris tells me. “Joseph Campbell talks of following your bliss; that’s what I did when I went to Nashville.” His heroes were Willie, Cash, and Roger Miller. When he was a janitor at Columbia, Kris passed along tapes of his music to Cash, who threw them into a lake. Nevertheless, Cash encouraged Kris to keep writing.

Pills and booze were the drugs of choice. “I thought the function of an artist was to burn, not rust,” Kris recalls. They stayed up for days and nights and weeks, Kris and pals like Mickey Newbury, writing songs and playing them for each other. Country musicians were considered trash by the Nashville business establishment, and songwriters were the lowest of the low. Music City in 1965 consisted of just two streets, Sixteenth and Seventeenth avenues. “The people I knew thought songwriting was a serious and worthwhile business, and I agreed with them,” he remembers. “I’ll tell you, it was like Paris in the twenties.”

One morning in 1967 Kristofferson landed a helicopter in Johnny Cash’s back yard. “He came stumbling out with a beer in one hand and a tape in the other,” Cash recalled last year during an interview for a BBC documentary on Kristofferson. One of the songs on the tape was “Sunday Morning Coming Down,” which Cash performed on his television show. Cash and Kristofferson had bonded into a sort of brotherhood of the damned. “Kris said I looked like a black snake,” Cash remembered. “He looked in my face and saw I was dying and wondered why. Then he wrote me a song.” The song was “To Beat the Devil,” a story about a poet who meets the devil in a bar, drinks his beer, then steals his song. It’s the kind of thing that William Blake might have written if he’d had Kristofferson’s sense of humor.

The seventies were a golden age for songwriters, much like the thirties, when the Gershwins and Hoagy Carmichael emerged not merely as songwriters but as trendsetters and celebrities. Writers like Willie and Kris forever changed country music, elevated it to an art. Kristofferson didn’t just write about love, he wrote about sex. “Take the ribbon from your hair / shake it loose and let it fall,” from “Help Me Make It Through the Night,” is out-and-out foreplay. “It was the first time anyone in Nashville had taken this direct approach to sex,” Willie says. Record producer Don Was once observed that Kristofferson was the most intelligent person he’d ever met. “That kind of enhanced consciousness can be a psychic burden to the poor soul who has got to live with it twenty-four hours a day,” Was said, “but it sure makes for some great music.”

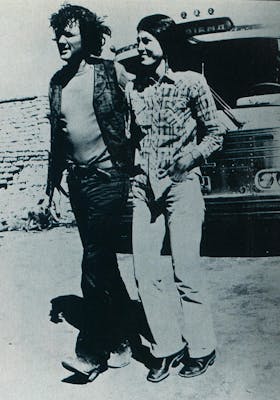

KRISTOFFERSON HAS ALWAYS THOUGHT OF HIMSELF as a songwriter, not an actor and certainly not a singer. “I sing like a bullfrog,” he told Combine Music founder Fred Foster, who replied, “Yeah, but a bullfrog who communicates.” Two songs in particular sealed Kristofferson’s reputation as a writer and indirectly led to his screen career—“Me and Bobby McGee” and “Sunday Morning Coming Down.” Dennis Hopper heard Kris’s tape of “Bobby McGee” and invited him to Peru to play a bit part in and write some songs for the cocaine-induced epic The Last Movie. Director Sam Peckinpah went wild for “Sunday Morning Coming Down.” Janis Joplin learned the words and music to “Bobby McGee” from a mutual friend, Bobby Neuwirth, and started performing the number in concert. And that led to her much publicized affair with Kristofferson.

Contrary to popular myth, the real Bobby McGee wasn’t Joplin but a secretary named Bobby McKee who worked at Combine Music. Kris wrote the song on assignment for Fred Foster, who came up with the title. Flying a helicopter over the Gulf, Kris decided that it should be a road song and wrote: “Busted flat in Baton Rouge, heading for the trains.” Listening to the rhythm of the helicopter and remembering one of Mickey Newbury’s songs, he wrote, “Bobby thumbed a diesel down, just before it rained …” Later he remembered the final scene of La Strada, Federico Fellini’s magnificent road movie, when Anthony Quinn realizes that he has dumped the only woman he truly loves, and that became the inspiration for the line, “Somewhere near Salinas, I let her slip away.” Kris explains, “It was that double-edged nature of freedom, when the pain of the loss more than equals the pleasure of the gain.”

Kristofferson’s meeting with Joplin came at the end of a drug-inspired journey that started as something else—a party at a New York penthouse in 1969. The merrymakers were a cast of characters emblematic of that psychedelic period: Odetta (an enormously gifted black folk singer), Ramblin’ Jack Elliott, Mickey Newbury, Bobby Neuwirth, Michael J. Pollard, Kris, and others. “There was much tequila and coke,” Kris remembers, “and in the middle of the night Neuwirth says to me, ‘Hey, Range Rider’—he always called me Range Rider—‘do you want to go to San Francisco to see Joan Baez?’ And Odetta says, ‘I want to go too!’ So we head straight for the airport, the three of us, Ramblin’ Jack playing us to the plane and Bobby telling everyone that we’re Peter, Paul and Mary, and Odetta’s been to the islands.”

Somehow, they never got to Baez’s house but went instead to Mill Valley, where Joplin lived with her dog, Thurber. Joplin was a big star at the time, Kristofferson a mostly unknown songwriter: All they had in common was that she had done “Bobby McGee” in concert and people had loved it. Though not physically attractive, Joplin had a sexual aura that could drive men to uncommon acts. “I’ve got a present for you, baby,” Neuwirth said, pushing Kristofferson into Joplin’s arms. A month later, Kris was still there. Joplin had been doing heroin, but she stopped completely during her affair with Kris.

“I lived with her, slept with her, but it wasn’t a love affair,” he tells me. “I loved her like a friend. She was very soulful, a passionate person but very childlike to me, a little girl in dress-up clothes. She was an unhappy person. Even though she was fun to be around, she felt that the only thing that made her attractive to the world was her art, her talent, her stardom. And she was intelligent enough to know that it was temporary. She told me, ‘Pretty soon you’re gonna be gypsyin’ down the road to be a star.’”

Kris tells me about his last night with Joplin. They had started with drinks at Barney’s in L.A., Janis in her famous feathered hat, the world at their feet. A kid came by the table to say how much he admired Janis, and she almost bit his head off. “That night in bed, I just held her all night long. We didn’t even …” Kris’s voice breaks and he looks away, toward the ocean. “I knew she was sad because she believed nobody loved her. She told me if things didn’t get better, she would go back on heroin and off herself. I didn’t believe her. I told her, ‘How do you expect to ever meet anyone if you snap their heads off?’”

Kris was staying at Joan Baez’s house in Carmel when news arrived that Joplin had died of a drug overdose. He believes her death was accidental. The night after she died, at the Landmark Hotel in Hollywood, most of Joplin’s friends met there. On that occasion, Kris heard for the first time Joplin’s version of “Bobby McGee.” Twenty-six years later, he saw a tape of her singing it at Threadgill’s in Austin. “To this day,” he tells me, “whenever I sing that line ‘Somewhere near Salinas,’ I think of Janis.”

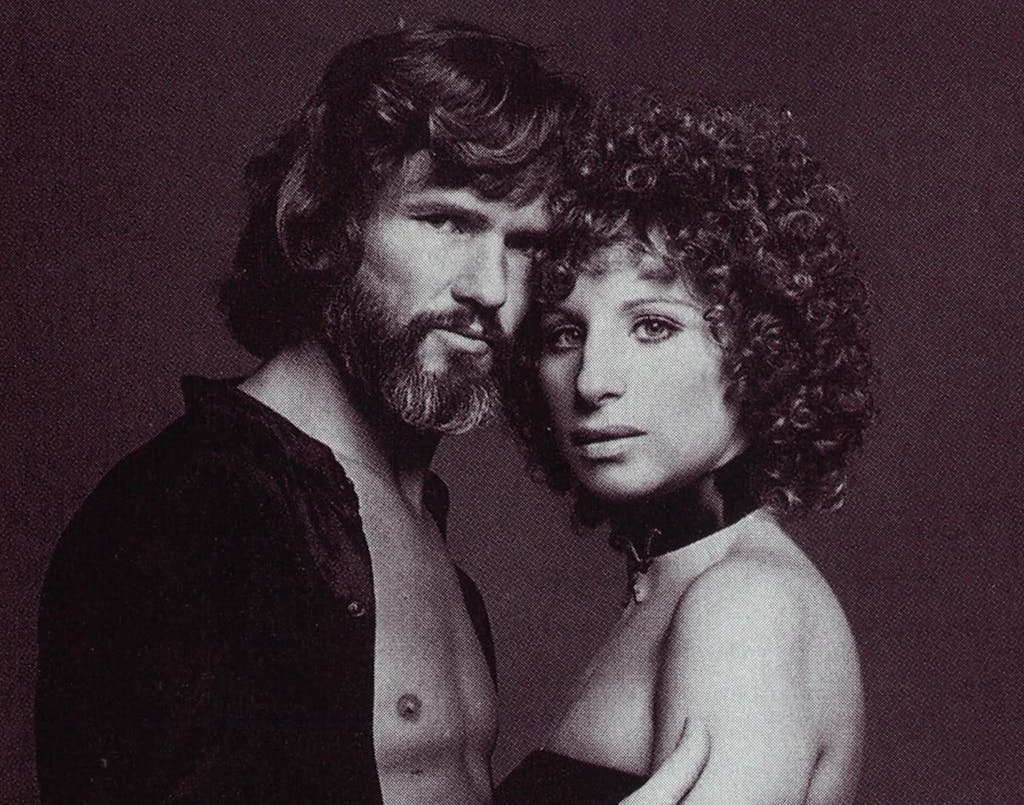

In 1970 Kris landed his first gig in show business, opening for Linda Ronstadt at the Troubadour in Los Angeles. A smashing review in one of the L.A. papers brought Barbra Streisand to the Troubadour to check out the young songwriter. Unfortunately, Kris didn’t show up. “I had been out with Hopper the night before, and I fell asleep in the parking lot,” he recalls. “When I woke it was dark, and I was supposed to be onstage.” Streisand came back two nights later, though. When they met backstage, the chemistry was instant. After that, the gossip columns crackled with items about Kris and Barbra.

The affair caused a sensation back in Nashville. “We’re shitting in the tall cotton now, aren’t we, son?” Cash said to Kristofferson. Almost overnight, Kris’s career was moving at warp speed. All the big names were recording his songs. He played Carnegie Hall and did a concert on the Isle of Wight with Jimi Hendrix, which turned out to be Hendrix’s last show. Hollywood began to notice too.

KRISTOFFERSON IS THE KIND OF FORCE that Hollywood has never been equipped to handle, a man who thinks for himself, measures truth by his own reckoning, and talks back. At the 1980 Cannes Film Festival, which held the premiere of Heaven’s Gate, a $36 million flop that nearly wrecked Kristofferson’s career, an executive of the studio that made the film warned, “Unless control is taken away from the creative people, our industry is headed for disaster.” To which Kris responded, “Who do you give it to, the uncreative people?”

Cracks like that don’t win points with the Academy. Neither did Kristofferson’s response to the asinine turf war between executives of CBS Records and Tri-Star Production Company over the filming of Songwriter in 1984. Abetted by producer Sydney Pollack’s weak-kneed refusal to intercede, the moguls not only sabotaged an excellent movie but also scuttled a brilliant soundtrack of songs by Kris and Willie. Kris celebrated this show-biz snit by writing songs about the executives, whom he dubbed for the ages: “Sydney the Snake,” “Danny the Dildo,” and “Wally the Wus.”

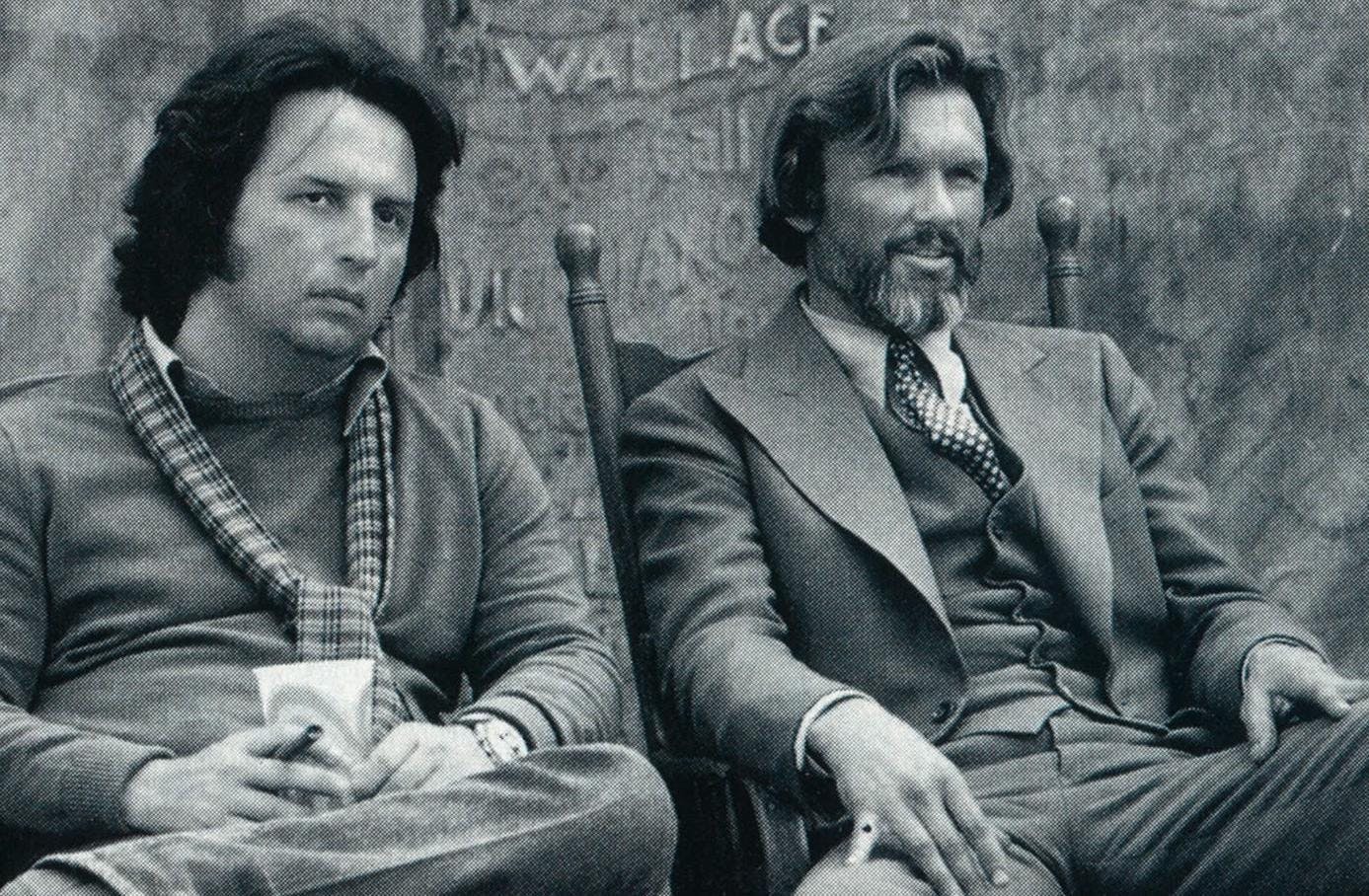

Kris’s first landmark role was playing Billy the Kid in Sam Peckinpah’s classic 1973 western Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid. The legendary director was throwing knives into his office door the first time Kristofferson met him. Within minutes they were lifelong friends. “We liked the same things—Mexico, women, and booze,” Kristofferson says. “Sam loved being surrounded by turmoil. He used it for energy. ‘F— MGM! Let’s go make a movie!’ Someone once said that Sam looked like a man tracking an animal much larger than himself. That’s a good description.”

At Kristofferson’s urging, Bob Dylan reluctantly accepted a part in the movie. Peckinpah had no idea who Dylan was and protested that the studio had cast him for purely promotional reasons. “The first time we watched dailies,” Kris remembers, “the projector was out of focus, so Sam walked up and urinated on the screen. I looked over at Dylan. He didn’t say anything, but I knew what he was thinking: ‘What the f— have I gotten myself into!’

“There were times when Sam wasn’t worth shooting, but he tried to make real films, and I loved him for it,” Kris continues. When Peckinpah died in 1985, Kristofferson headed up a host of celebrities who honored him. Alan Rudolph recalls that Kris began by chewing out Hollywood for not fully appreciating Peckinpah. “It was a terrific statement about Peckinpah, about Hollywood, and about Kris’s loyalty and convictions,” Rudolph said.

Acting for Kristofferson is more a cause than a profession. He succeeds at it for the same reason he succeeds as a singer and a songwriter: because he knows his range and has true convictions. Radicalized by his experiences, Kris finds political nuances—even messages—in every role he accepts. Kris says that Heaven’s Gate was an attempt to show the fatal flaw in our society: We care for money more than for people. In his mind Lone Star is a dark allegory of the American experience in which the three sheriffs represent three sides of history—the genocidal, the merely bigoted, and the racially semi-tolerant. “Now, if you billed it that way,” he admits, “nobody would come and see it.”

Many of the fans of Lone Star, myself included, believe that the film demonstrates that Kristofferson belongs in an elite class of strong, silent, honest actors like Gary Cooper, Robert Ryan, and Gregory Peck—the three actors he most admires. Kris is believable as the corrupt and murderous sheriff Charlie Wade because he has absorbed a larger measure of the character than meets the eye. Sayles had the good judgment to understand that Kristofferson, like Cooper, is an actor who nails his character through an internal process, that on-screen he does a lot without appearing to do anything. Alan Rudolph, who directed Kristofferson in Songwriter and 1985’s Trouble in Mind, has observed, “As the camera got closer to him, the movie got better.”

In 1974, Kristofferson appeared in Martin Scorsese’s Alice Doesn’t Live Here Anymore, but his film career got its biggest boost in 1976, when Streisand chose him to play the self-destructive superstar in A Star Is Born. Streisand played the unknown whose star rises as Kristofferson’s fades and dies. Though they were no longer an item—Streisand was living with Jon Peters, who co-produced the film with her—the chemistry was still there, sparking rumors of a renewed romance. There were also stories about how Streisand’s arrogance and overbearing attitude inspired the crew to put human excrement in her makeup.

That’s not exactly what happened, Kris tells me. “We had come back to finish a scene where the two of us were rolling in the mud, and Willie Perez, the wardrobe guy, had wet down some fuller’s earth to look like mud. In the middle of the scene, Barbra stops and tells the director, Frank Pierson, ‘This stuff smells like shit!’ I smelled it and it did. Pierson says he doesn’t want to talk about it, and we go on with the scene. I’ll say this, Barbra took it a lot better than you’d think.

“Barbra opened doors for me,” he acknowledges. “She put me in a whole different category.” After the film premiered, Streisand and Peters gave Kristofferson a silver joint case inscribed, “A superstar is born—let it be an easy birth.” Prophetically, Kristofferson’s movie career skyrocketed.

Kristofferson was convincing as the booze-and-drug-addled superstar because during the entire course of filming, he was stoned. “I was drinking two bottles of whiskey a day,” Kris tells me. He had been riding the whiskey-pills-and-pot roller coaster hard and fast since his early days in Nashville, and now it was catching up with him. Watching his own body on the screen, Kris had a premonition of death. He saw his young daughter Casey standing alone, without him. “The idea of Casey growing up without me was inconceivable,” he says. So Kris’s life made its third hard turn: He stopped drinking and started running seven miles, swimming fifty laps, and working out on a rowing machine daily. He also reconnected with his spiritual life, not by joining a church but by making a private accommodation with God.

It happened while Kristofferson was on tour in Europe. He learned that his daughter Tracy had been injured in a motorcycle wreck and was unconscious and probably paralyzed. A friend in Alcoholics Anonymous had told him, “If you don’t believe in God, ask for something impossible.” Flying to California that night, Kris started making a deal with God, saying, “Please don’t let her be paralyzed.” “When I walked into her room at the hospital, she was in a coma, tubes running everywhere,” he tells me. “A minute later, the doctor says, ‘Look!’ Her leg had moved. I’m thinking, ‘Okay, I’m your boy!’”

Kristofferson’s marriage to Coolidge began to fall apart in the late seventies, just as Kris started filming Heaven’s Gate. Kristofferson always had problems avoiding women: Stand him on any street corner in the world and they will flock around him like magpies around a tree of ripe apricots. What pushed Coolidge over the edge, however, wasn’t infidelity but the passionate love scenes between Kris and actress Sarah Miles in The Sailor Who Fell From Grace With the Sea. The final straw was when Playboy published the outtakes from the film.

Director Michael Cimino remembers how the divorce devastated Kris during the six-month filming of Heaven’s Gate. He speaks of Kristofferson’s “Lincoln-esque black moods” and says: “There were days when one could almost not talk to him. He was literally at the bottom of the well and one had to find a way to pull him back up to where he could even speak… A lot of the agony and pain you see on the screen is quite real. It’s something beyond acting.”

The failure of Heaven’s Gate symbolizes Kristofferson’s star-crossed film career, always a step short of greatness. Cimino’s next project was supposed to be a remake of The Fountainhead (1949), with Kristofferson playing Gary Cooper’s part. “Nobody on this planet could have played Gary Cooper like I could,” Kris tells me. But when Heaven’s Gate went south, so did the new project. At the time, Kristofferson was among the ten most bankable stars in Hollywood, right up there with Robert Redford and Paul Newman. “After that,” Kris tells me, “I couldn’t get a job.”

IN RECENT YEARS, KRISTOFFERSON’S music as well as his life has become increasingly politicized, not always to his advantage. Songs about Vietnam, Wounded Knee, Martin Luther King, Gandhi, and Christ, while noble and well intended, are hardly toe-tappers. Willie has hinted to friends that he dearly wishes that Kris would shut up and play “Me and Bobby McGee,” but of course he can’t say that to Kris. Both Willie and Kris play a lot of benefits for farmers, Native Americans, human-rights advocates, and environmental causes, but Willie does it with a minimum of lectures.

Kristofferson’s reputation as a writer and a performer has diminished to the point that his acting career now subsidizes his music. During the filming of Lone Star, a local production assistant was furious to discover that it wasn’t the hunk Matthew McConaughey she was driving to the airport but some geezer named Kristofferson. Like his other albums this decade, his 1995 release, A Moment of Forever, sold poorly. This is unfortunate because it was produced by Don Was, one of the best in popular music, and contains some good love songs, great satire, and a wonderful tribute to Peckinpah, which opens:

I have been with the best that the bastards could muster

From Danny the Dildo to Sydney the Snake

And I feel like a working girl pausing to wonder

Just how much screwin’ the spirit can take.*

Kris admits that his passion for causes ebbs and flows. But he once said, “You’ve got to think of the consequences if nobody speaks up. What it really gets down to, though, is living with yourself. If you don’t live by the principles you believe in, then you become this hollow person.”

What finally radicalized Kristofferson was the public reaction to his 1986 television miniseries Amerika. He caught hell from both the right and the left. The film was a fantasy about a Soviet invasion of the United States, with Kris playing the anti-communist leader of the U.S. resistance. The original screenplay, which he rejected, pushed a right-wing agenda, painting the United Nations as a tool of the Soviets. Kris agreed to the role only after most of the negative references to the U.N. were taken out of the script.

This infuriated right-wingers, who accused him of sabotaging the project. Left-wingers were even more ruthless. “Don’t think you can atone for Amerika just by marching with us,” a woman at an anti-nuclear demonstration in Nevada told him. “They acted like I made a film for the Nazis,” Kris says. The experience helped focus Kristofferson’s political ideas. In the weeks that followed, he played a number of human-rights benefits and made several trips to Nicaragua. He got to know the country’s president, Daniel Ortega, who invited Kris to sing at the anniversary of the revolution that put him in power.

On one of his trips to Nicaragua, Kristofferson was asked to visit Eugene Hasenfus, the Air America crewman whose plane was downed while flying supplies to the contras. Kris took the prisoner a copy of the book Fire From the Mountain: The Making of a Sandinista, then told him the story of Tracy’s miraculous recovery and repeated the challenge of faith: “If you don’t believe in God, ask for something impossible.”

Kris tells me now, “All the time I’m telling Hasenfus this story, I keep thinking: Why am I doing this? I knew that the hard-liners intended to make an example of him, that he’d probably serve thirty years, so why am I building up his hopes? That night, Lisa and I fly home to Maui, and when I check my answering machine, I learn that Hasenfus has been released and is already back in this country.” Kris smiles and adds, “I don’t know if it bolstered his faith, but it bolstered mine.”

Kris walks me to the car, his three dogs nosing him for attention. We shake hands and I realize again how much I admire him. I once told Kris that I thought of him, Willie, and Billy Joe Shaver as the Byron, Shelley, and Keats of our time. “I can’t argue with that,” Kris replied. Driving back to the airport in Maui, I keep remembering how the notion of Kris’s being considered for an Oscar was more important to me than it was to him. It would be nice, but it’s nothing that he needs. When you’ve been Kris Kristofferson, what else is there?

- More About:

- Music

- Film & TV

- Longreads

- Kris Kristofferson

- Janis Joplin

- Brownsville