This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

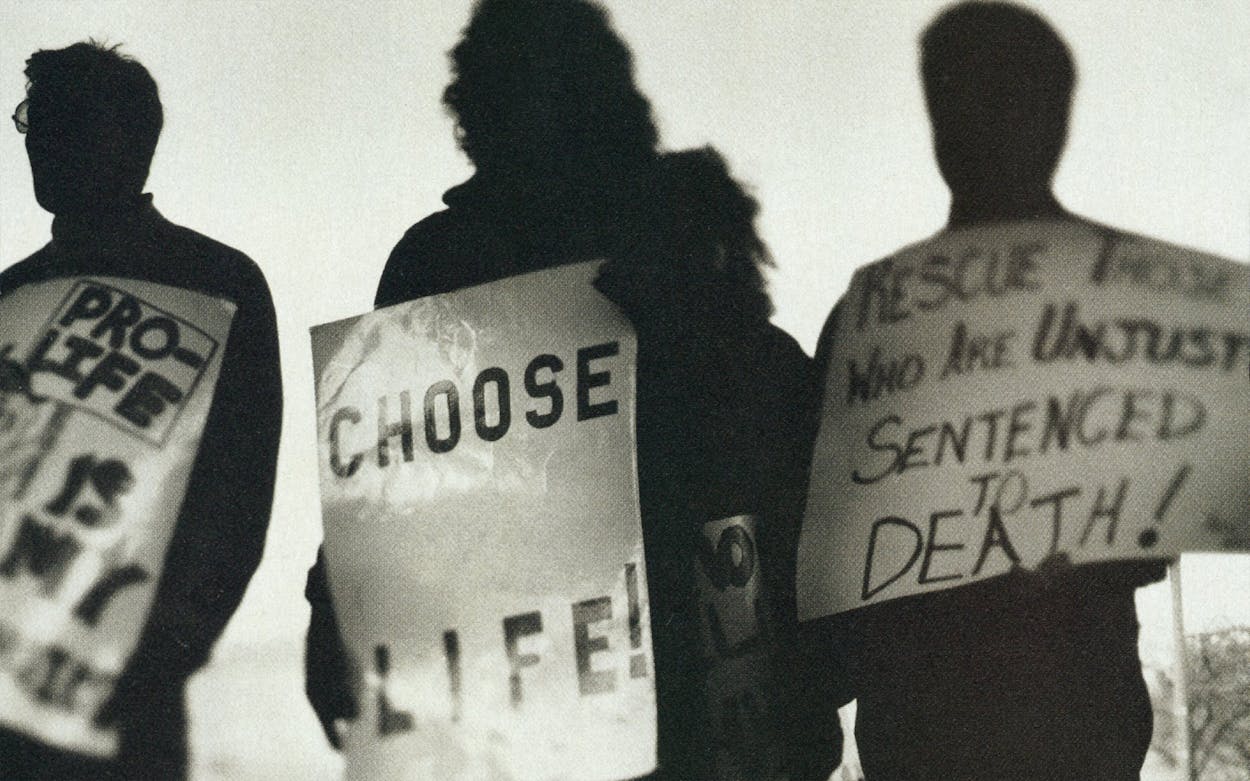

The innocuous white office building at the intersection of Fitzhugh and the Central Expressway in Dallas is an unlikely site for a battleground. Speeding between Ken’s Mufflers and the headquarters for Young Life, most drivers miss it entirely on most days. Saturdays, however, are different. Picketers line the sidewalk, proselytizing (“Finding God is like a great sale at the Gap”) and handing out pamphlets (Children—Things We Throw Away?). They carry placards, the poster of choice being a small blackened baby resting peacefully beside an adult hand holding a single red rose. “ABORTION IS MURDER,” the poster says. Should you pull into the driveway behind the building, the picketers will swarm toward you and, prohibited from crossing onto the property, scream at you from the sidewalk. “Please don’t kill that baby!” they might shout. A particularly zealous protestor might even holler, “That’s right—go and spread your legs for the doctor so you can go out and fornicate again!”

Travel across the parking lot, through a courtyard, and up a flight of stairs, and you will find two businesses, facing off across a landing. One is the Routh Street Women’s Clinic, where doctors perform an average of four thousand abortions a year. Across the way is the White Rose Women’s Center, which advertises itself as a confidential abortion-counseling service but which, supported by Catholic organizations, is absolutely dedicated to eradicating legal abortion. On Inauguration Day it was even more apparent that all the bitterness and horror of the abortion fight could be found at this single address in Dallas. “NO TRESPASSING,” ordered the usual sign on the door to the Routh Street clinic. “Anyone entering these premises to disrupt or protest a woman’s right to have an abortion will be considered a trespasser and will be prosecuted.” Three banners in the White Rose’s windows reveal the center’s true orientation: “SOMETHING MUST BE DONE,” the first said. “SOMETHING WILL BE DONE,” said the third. In between was a photograph of the bloody, severed head of a 27-week-old fetus, held aloft by a pair of forceps. The universal “no” sign was splashed across the picture.

Sixteen years after abortion was included in the right to privacy by the U.S. Supreme Court, it remains the issue that will not go away. Divisive public debates like the Vietnam War, Watergate, and Reaganomics have come and gone since the 1973 decision in Roe v. Wade, while abortion climbs ever higher on the public agenda. A new kind of protestor, more vocal and more violent, is emerging. Hundreds of picketers were recently arrested in Austin and San Antonio; in Dallas arsonists set fire to three abortion clinics at Christmastime. Now the Supreme Court has agreed to hear a Missouri case that gives it the opportunity to overrule Roe v. Wade. If it does, state legislatures will be free to make abortion a crime, as it used to be in Texas. Fifty state capitals will become battlefields.

As successful as the anti-abortion protesters have been in generating publicity and political pressure, they have been less successful in affecting the behavior of Americans. The visit to the abortion clinic has become a ritual of life in the United States. Thirty percent of all pregnancies end in abortion—an estimated 20 million since 1973. Abortion is the most common outpatient surgery in America.

Still, abortion remains the great taboo. We have learned not to think about it, much less talk about it. (“King’s ex,” a friend whispered. “Do you think it’s murder?”) As pressure to ban abortion grows, members of the pro-choice majority keep their contradictions to themselves: We want abortion to be legal and painless, but don’t want it taken for granted. We want to see abortions as heroic for poor women who shouldn’t overpopulate the earth, but selfish for yuppie couples. We want to condemn men and women who do without contraception—unless they happen to be friends or family. We want to call it a baby if it’s wanted, but a fetus if it’s not.

For someone still asking questions, the squat, dingy building on Central is the place to go. Here the two sides present their cases to the world. Six days a week the battle rages, immune to time, events, and the muddled thinking of those who try to find common ground.

Just a Statistic

Even to the staunchest advocate of legal abortion, the Routh Street Women’s Clinic is oppressive. To compensate for the drawn blinds, which protect patients’ privacy and defend them from the insults of protestors, the clinic owners have painted the walls a promising peach and decorated them with posters quoting feminists like Margaret Sanger (“No woman is ever truly free until she can control her own reproduction”). A television featuring rented movies or talk shows—Oprah was chatting up Donald Trump on one of my visits—seems to prolong the tedium rather than ease it.

The truth is simply inescapable: The women who crowd into this waiting room are pregnant when they arrive in the morning, and by late afternoon they aren’t. All sorts of women occupy the sofas and chairs, from prosperous, pony-tailed coeds to middle-aged Hispanic women in flimsy clothes that don’t ward off the cold. Sometimes there is a child or two, often a husband or boyfriend. Mothers accompany daughters, girlfriends come with classmates; some women sit alone, listlessly flipping through magazines. The scene reminds me of something a friend told me recently: that the lasting impression of her abortion was not a feeling of relief or regret but the realization of her very ordinariness. “I found out I was just a statistic,” she told me.

One of today’s statistics is a 23-year-old Hispanic woman I’ll call Sylvia Muñoz. With a cascade of black hair pulled off her face by a large plastic clip, her short denim skirt, and a Neiman Marcus sweatshirt, Sylvia looks more like a high school girl than the mother of a two-year-old. But today she is seven and a half weeks pregnant, and she wants an abortion. In one of Routh Street’s small, windowless rooms, Sylvia faces her counselor, a tiny, angel-faced woman named Daneille, whose job is to divine whether a patient really wants the abortion she has requested. Daneille is not convinced Sylvia has made this decision on her own; she worries that Sylvia’s husband is making her have this abortion. Because I speak Spanish, I have been recruited to translate. “No,” Sylvia says evenly. “Estamos de acuerdo”—“We’re agreed.” Even with that answer, Daneille is unconvinced. Offering to lend Sylvia a quarter, Daneille asks her to call her husband and ask him to come to the clinic.

A few minutes later Felipe Muñoz arrives, a small, respectful man wearing jeans, a T-shirt, and a Greek sailor’s cap. The slight mustache sprouting above his upper lip makes him look even younger than his wife. Like Sylvia, he is taken aback by Daneille’s concern. The four of us go into another windowless room and place ourselves on metal folding chairs. Daneille sits in the center, a clipboard in her hand. Gently, she elicits their history. The Muñozes are poor. Sylvia is from Central Mexico and met Felipe when she moved to Laredo. She has no family in Dallas—a sister, she says happily, is visiting—but Felipe’s entire family lives here. He does not want Sylvia to work; he supports his family on his salary as a busboy. Sylvia has had little to no prenatal care—it is a long wait for an appointment at the public health clinic, and then it’s an all-day affair when she finally gets one. Even though she has tried to be vigilant about birth control, she became pregnant after twice forgetting to take her pills in one cycle. “It’s my fault,” she says.

Most of the women who come to Routh Street are in similar straits. The clinic is a monument to the awesome failure of birth-control education. The stories of biological roulette, wishful thinking, and just plain ignorance observe no lines of race, class, or education. In Routh Street’s waiting room are poor girls who have never had a pelvic exam, as well as educated women who hoped that they could not get pregnant if they were nursing or having their periods. There are women who believed that they could abort by doubling up on birth-control pills and taking a bath in hot mustard; there are women, coming in for their third or fourth abortions, who never use contraception at all.

Felipe and Sylvia tell Daneille that they cannot afford another child. Finances are the reason most married couples cite when requesting an abortion, but counselors have learned that it is often just one of many, the easiest to express and the most difficult to challenge. Daneille then asks about their religion. Both of them are Catholic, but when Daneille reminds Felipe that his church prohibits abortion, he greets the news with a shrug.

Sylvia grows impatient with the questions and finally interrupts. Since she kept taking birth-control pills after becoming pregnant, would there be something wrong with this baby? (The Muñozes do not use “embryo” or “fetus”; they talk about “el baby.”) Daneille says she will ask the doctor and leaves the room. The Muñozes show me a photo of their child, a round, laughing little boy dressed in short pants and a jacket and a bow tie, his hair slicked precisely over his forehead. Daneille returns with the news that taking the pills poses very little risk, but Sylvia’s concern about the baby’s health causes the counselor to reopen the questioning. If it weren’t for that worry, would Sylvia want the abortion? Sylvia and Felipe look at each other intently. “There is no money,” Felipe says finally.

Then Daneille picks up a plastic model of the female reproductive system and begins to explain the procedure. Sylvia nods impatiently and says something to her husband. “She says she remembers this from the last time,” he tells Daneille.

The counselor gives a start. She’s had another abortion? Yes, Sylvia answers, here, last year. Daneille repeats her question: If this baby could be born normal, would they want it? They look at each other again, and then look away. In unison, the answer is no.

After teaching Sylvia what to do if she misses two birth-control pills again, Daneille is ready to take her down for lab work. Will Felipe stay with her? He shakes his head swiftly, embarrassed and offended. Annoyed, Sylvia asks if I will go with her, and I agree.

While Sylvia waits to give her blood sample, Daneille collects the fee. Sylvia reaches into a change purse and pulls out a wad of cash, $250. Sharing a small anteroom with two other women—an unmarried schoolteacher here for a second abortion, a morose mother of one here for her first—she tells me she is nervous.

About half an hour later we go downstairs into a room that is cold by design, to make the surgery go easier. Sylvia shivers when Daneille tells her to get undressed and slip into a paper smock. “My side hurts,” Sylvia says, placing her fingers over her abdomen. Then lying on the table, she tells me she is worried about what her sister will say. “She’s going to think I’m crazy,” Sylvia says.

Lea Braun, the doctor who is one of the clinic’s owners, enters and begins a pelvic exam. A graying man with the practiced weariness of a public-health doctor, he says that Sylvia’s pain is probably a cyst, aggravated by the pregnancy, that will most likely dissolve.

With a clank, Dr. Braun opens a bag of sterilized instruments on a metal table. Sylvia begins to tremble from an injection of painkiller and epinephrine, a drug used to keep the patient’s heartbeat steady. While Daneille tells Sylvia that the procedure will go better if she breathes slowly and deeply, Dr. Braun inserts a speculum and cleans the walls of her vagina with a Betadine solution. Then he inserts a tube and turns on a machine, which, roaring to work, sucks the life out of Sylvia. Blood and tissue beat against the walls of a once-clear tube, like rain lashing at a windowpane, filling a plastic container. Sylvia writhes on the table and cries out; the color drains from her face. Her body goes rigid, as if she fears that the machine might devour her as well. “Just a few minutes more,” the doctor says.

When the abortion is over, Daneille and Dr. Braun leave us alone in the room again. Sylvia lies under the drape, pale and limp. When she gets up, she leaves behind a puddle of blood. Soon a nurse enters and directs us to a small, dim recovery room, where there are easy chairs and heating pads, cold drinks and cookies. Four women—one in each corner—are quiet, in varying stages of pain. Detached, Sylvia nibbles on a cookie.

By now, it has grown dark, and the clinic is closing. As I say good-bye, I know that the Muñozes will go home to the one child they feel they can properly care for, and I know that this abortion may help them escape the grip of abject poverty. But this knowledge does not stop another feeling, as persistent as the chill in the parking lot that night: that somehow I have stepped into the landscape of a common, everyday nightmare.

The Horror Show

The White Rose’s waiting room lacks the bustle of Routh Street; the cramped, harshly lit entry is empty when I arrive. I am there as a patient under an assumed name—when I called to make an appointment as a reporter, I was brusquely turned away. (“That’s your problem,” snapped center co-director Gerri Everts when I told her I was trying to examine the abortion conflict from both sides.) I am seen immediately by a kindly woman who escorts me to a small office in the back. She is middle-aged, slight, and prim in her long skirt and pearl-buttoned sweater. Pushing aside a paperback of some works by Catholic theologian Thomas Merton, she asks me a few questions: my address, my job, my “boyfriend’s” name. The woman asks how I feel about abortion, and I tell her the truth: I am ambivalent. Then she asks me for a urine specimen for the pregnancy test. When I return she takes me into a small room that has a television with a slide carousel on top, explaining that the center likes to offer a short presentation while women wait for their test results. Then she turns on the projector, turns off the light, and leaves me alone.

What follows is a cross between a fifth-grade hygiene film and Nightmare on Elm Street. The presentation is Socratic in form—at crucial intervals, a young woman, her back to the camera or her face obscured, poses the big questions, like “Isn’t the fetus just a bunch of cells?”

In the first portion a male narrator tells of recent deaths from abortion, of abortions on women who were not pregnant, of the calamities of a perforated uterus, of high fever, thrombosis, or brain damage. Next, he personifies the fetus: “He already knows what he likes to eat,” he asserts, “At sixteen weeks he can sense pressure, pain, and respond to sound. He swims with a natural swimmer’s stroke.” I’m instructed that “fetus” is wrong; “young one” or “baby” is correct. To prove that a fetus is separate from—as opposed to a part of—the mother, it is compared to an astronaut floating in space, connected to the capsule by long tubes.

On the beginning of life, the film leaves no room for doubt: “Fertilization is the greatest and most meaningful time of life,” it states. “At fertilization the total human being is there.” The real horror show follows: bloody fetuses piled in trash cans, photos in which tiny limbs can be seen protruding from what looks like coarsely ground round.

After the film, the woman comes back into the room with the news that I am not pregnant. Then she asks a few more questions about my boyfriend and urges that we marry, suggesting that life is so much easier when one is “protected.” She gives me a pamphlet that warns against premarital sex—it recommends channeling sexual energy into sports. I rush to my car when the interview is over, like a child escaping a perverse carnival sideshow.

I understand my unease better after a counselor at Routh Street directs me to a woman I’ll call Isabel Wallace. An eager young woman of 26 with shimmering dark hair, Isabel, who comes from a strict blue-collar family, is married and has a 20-month-old daughter. Like Sylvia Muñoz, she became pregnant when she twice forgot to take her pills. Overwhelmed by the responsibility of one child and concerned about tensions in her marriage, Isabel knew she wasn’t ready to have another child. Although her husband longed for more children, he told his wife, “I want what you want.” It was a doubly difficult decision because Isabel’s parents are devout Catholics active in the right-to-life movement. Her parents had often told her that women who had abortions were stupid or just couldn’t keep their legs together. At the State Fair Isabel’s mother asked her to give $1 to the right-to-life booth—in return, she had received a pin of tiny silver feet. It is still in her closet at home.

Isabel had made one call to Routh Street for information. She called again from work, but she was nervous and did not recall the name of the clinic; she looked under “Abortion” in the Yellow Pages and found a place at the address she remembered. She got the White Rose. When a woman answered, Isabel said that she had spoken to them about an abortion earlier and wanted to come in now. Could the abortion be performed that day? Yes, the woman told her, if her pregnancy test was positive. She was quoted a price of $300.

The day Isabel went to the center, she told the woman who greeted her that she had come for an abortion. The woman did not inspire confidence. “She looked like she needed counseling,” Isabel told me. “She was red-eyed, like she’d been crying for days.” Isabel went through the same steps I did. After the slide show, the woman came back with surprising news. “Congratulations, you’re between nine and a half to twelve weeks pregnant,” she said. Anxiously, she was cradling some books close to her chest. As Isabel tried to steady herself—she was convinced she was only seven weeks pregnant—the woman put the books down, open to pictures of three-month-old fetuses, and slid them across the table to Isabel. “Don’t you ever think of your baby?” she asked. Then she asked Isabel if she would consider adoption. “I cannot carry a baby for nine months and then give it up,” Isabel said. “I’m a mother, I can’t do that.”

The woman then agreed to call the doctor to arrange the abortion. She disappeared for twenty minutes and then started in again. “The doctor is busy now,” she said. Then she demanded: “Why do you want to give this baby up?”

“Listen, my husband’s into drugs and we’re getting a divorce,” Isabel told her, starting to lie.

“Have you thought about turning your husband in to the police?” the counselor challenged. When Isabel resisted, the woman tried another tack. “You don’t think you could work now and take time off when the baby comes?”

“No,” Isabel said. “I can’t leave my daughter alone.”

The counselor upped the ante again. The White Rose would send her to a home in Arkansas. “No charge,” she pleaded. “The airfare’s free, the doctor’s free—you can take your daughter with you, and your new baby will be adopted right away.” The home was beautiful, she said, with high white columns on the front porch.

“I can’t leave town for that long,” Isabel said, raising her voice.

“Then move in with me,” the counselor begged. “You can stay with me until you get some money.” Trembling, she added, “My parents died at an early age. I was put in a foster home. I’ve had to struggle with my life,” she cried. “But unwanted children can find good homes.”

With the room closing in, Isabel held firm. “Am I going to get to see the doctor today or not? I’ve made my decision.”

Finally, the woman confessed that the White Rose didn’t do abortions. Suggesting that abortion clinics aren’t medically safe, she promised to help Isabel arrange one at a hospital. Desperate, Isabel agreed to come back soon to make the arrangements. On her way out, disaster struck. She ran into a neighbor of her mother’s, a White Rose volunteer. Acknowledging that she had had a pregnancy test and nothing more, Isabel fled.

From a nearby phone booth, she called Routh Street, whose signs she recognized on her way out of the White Rose. She had an abortion that day. Lying on a table, Isabel remembered a high school friend who had had three abortions. “It’s not so bad,” the friend had told her of the procedure, “It kind of feels like f—ing.” On the table, Isabel thought, “This feels nothing like f—ing.” She wanted to ask to see the remains to say good-bye but had lost her nerve. Instead, when it was over, she whispered good-bye under her breath and added, “God forgive me.” Then Isabel went home and told her husband, “I’m going to hell now.”

As Isabel was trying to put her life together a few days later, the phone rang. “Congratulation,” her mother said. “You’re going to hear a little more pitter-patter through the house.” The neighbor had called to tell her that Isabel had been in the clinic for a pregnancy test and she was sorry she hadn’t been able to counsel her. She said she didn’t want to be starting trouble, but she knew Isabel’s mother would want to know.

“I don’t know, Mom” was all Isabel could say. “Something doesn’t feel right.” Finally, after her mother called several more times, Wallace told her that a doctor had found fibroid tumors—a Routh Street clinic doctor had indeed discovered them after Isabel had complications following her abortion. She had had to have a D&C, short for “dilation and curettage,” a procedure in which the uterus is vacuumed and scraped clean. “So if I was pregnant, I lost it,” Isabel said.

“Oh,” her mother said softly.

“She knew,” Isabel says of her mother. “She knew.”

The Power of Faith

The Routh Street women’s clinic is owned by Lea Braun and a lawyer, but the person whose resolve has shaped the place is Charlotte Taft. The director of the clinic, Taft, 38, is a tall woman with blond curls and a face that manages, like her disposition, to be doleful and animated at once. She is such a confident and articulate advocate—“Americans favor abortion,” she gibes, “only in the case of rape, incest, and their own personal circumstances”—that it is easy to lose sight of one glaring similarity she shares with the opposition: an absolute, unrelenting commitment to her cause.

Like her counterparts in the anti-abortion community, Taft always has a book to recommend or a fact to cite (abortion was legal in the United States until the 1830’s; the Bible makes no mention of abortion at all, indicating that it was accepted practice). Sometimes she views the threat to legal abortion as a personal failure; other times she is outraged by the lack of public support. “If a red dot appeared on the forehead of women who’ve had abortions,” Taft says, “the right-to-life people would have to wear red dots.” So dismayed is Taft by the lack of concern for women’s rights that she once considered refusing abortions to all patients who had voted for Ronald Reagan. Then she realized she would be out of business if she did.

Even as a young girl, Taft’s life was clouded by abortion. She came of age when abortion was illegal and a leading cause of maternal death. Taft donated a small inheritance from her grandfather to pay for a neighbor’s “therapeutic” abortion—one approved by a hospital board. Later she learned of her mother’s self-induced abortion with a knitting needle. “As a child, I was outraged,” she recalls. “I knew nobody should be able to tell a woman what to do.”

As an adult, Taft has paid a price for her advocacy. Her homosexuality was revealed on a television talk show by Dallas right-to-life president Bill Price. Her garage was burned and her phone lines cut. Protestors regularly call her a murderer. She gets hate mail on her birthday (“Another year for Charlotte Taft / Another poem for you I draft / Another year of feticide insane / Another 4,000 down the drain”).

Still, the Routh Street clinic is fueled not just by Taft’s unshakable belief that women who do not want children should not be forced to have them, but also by her vision of women as “moral agents.” “I want to inspire women to think about the way the world should be,” Taft says. This is an ideal born in the trenches, under fire. Where the rest of us may associate abortion with death, Taft and her counselors see abortion as an opportunity for life, for the woman to begin again.

Like abortion foes, Taft believes the decision to opt for an abortion is a serious one. Extensive counseling is the rule here. “My concern is that the woman make a choice she can live with,” said one counselor, preaching the Routh Street gospel, “because it is something that she’ll live with for the rest of her life.” Routh Street doctors do not use general anesthesia, partly because it is unnecessary for early abortions and also because Taft believes women should take responsibility for their actions. If a counselor determines that a woman does not really want the abortion or that she will suffer severe psychological damage as a result, the clinic will send her away, with the name of an adoption agency if it is requested. The clinic turns away 5 to 10 percent of its patients per week, though some of those receive abortions later, after more counseling. No one leaves the clinic without a prescription for birth control, and a look at the literature there shows Taft’s determination to take on topics long abandoned by most families and schools. Along with If You’re Not Ready to Have a Baby . . . Say No to Sex—Or Yes to Birth Control, there is Your Daughter Wants to Talk and My Parents Would Kill Me: On Abortion, Especially for Teens.

There can be no doubters at Routh Street. Somehow it’s no surprise that many of the counselors have had abortions themselves (“It’s helped me to process a lot of information to work here,” one said); others, like the counselor who told a press conference of the child she gave up for adoption, clearly wish they had. The semantic somersaults created by abortion politics are the norm here. When I used the term “pro abortion,” I was gently corrected. (“We say ‘pro choice,’ ” a counselor told me, supplying the politically correct alternative, “because no one is really pro abortion”) Reflecting the national trend, the majority of Routh Street’s abortions are performed in the first trimester, but no one here agonizes over the when-is-a-fetus-a-baby question. “Scientifically, there is really no dispute over whether or not the embryo or fetus is life,” the pamphlet How Can I Decide? states. “It is life. The moral question is whether it is of the same kind and significance as the human life of those already born.” That the outside world views abortion-clinic workers with everything from mild distaste to outright disgust only stiffens their resolve.

Counselors are less concerned with the outside world than with the vast, secret spectrum that makes up our private lives. “No one wants to look behind the circumstances that bring women into abortion clinics,” Taft says. Routh Street’s counselors do, in fact, see women who became pregnant from rape and incest, poverty-stricken women for whom life presented no good choices, women who for innumerable reasons never learned to see themselves as anything but victims—who insist that abortion is murder, for instance, but demand one because otherwise they might lose their husbands, lovers, or jobs. Anyone who spends even the briefest time at the clinic will come to grasp Taft’s belief that abortion is a symptom of greater problems in women’s lives. Sometimes contraception fails, but sometimes women get stuck in relationships that are going nowhere; abortion, like pregnancy, becomes a way to force a relationship forward, sometimes to a test, sometimes to its end.

Even Taft admits that few women ever confront these truths, much less want to tackle them on the day of their abortion. “It’s the worst feeling in the world to see a woman back for another abortion after I’ve counseled her,” one counselor told me. “I’ll spend days after asking myself what I did wrong,”

Still, the work must go on. It’s a keenly contemporary labor, part comforter, part mourner, part undertaker. On one Saturday counselors console a fourteen-year-old while a nineteen-year-old howls in the next room. As patients rest in recovery, counselors push the wheeled aspirators into a small pathology lab. There the contents of each abortion are dumped into a colander and the excess blood rinsed away in a sink. The remains are placed in a dish on a light table; it’s a technician’s job to be sure the doctor emptied the uterus entirely. Poking at the bloody mass on the dish with gloved hands, the technician searches for a cord and sac; in a pregnancy over nine weeks, she checks for the presence of two feet and two hands. When she finds them, she holds the tiny fetal parts against a ruler to be sure that their size jibes with the sonogram measurements estimating the age of the pregnancy. That work done, the remains are disposed of as medical waste.

At Routh Street, you’ve got to believe.

The Sidewalk Counselors

Every Saturday morning picketers arrive at 4228 N. Central. They have been staking out the Routh Street clinic for three years. Among radical anti-abortionists, like those belonging to Operation Rescue, picketing has fallen out of favor—the latest thing in abortion protest is to block clinic entrances in hopes of being arrested. But this crowd is not interested in the latest trend.

Many of them are students from Christ for the Nations, an unaccredited Bible college in Oak Cliff. Abortion protesting—or sidewalk counseling, as the protesters prefer to call it—is a requirement for graduation there, part of the moral-issues-ministry program. The students are a serious lot. (“People act like you’re not here, like you’re some freak,” says a tall, extremely thin young man, shivering on an icy day. “We’re here, we’re representatives of life. We’re here to save!”) Their placards, sometimes lettered with magic markers or decorated with birthday cards, are more reminiscent of high school pep rallies than the most bitter battle in America today. The members of the Abortion Abolition Society are less amateurish. Their most vocal member is Winston Wilder, a burly, bearded man whose cold eyes are suffused with fury. Wilder’s wife, Jane, is a regular here too, a round, country-faced woman who often clutches a life-size pink-plastic eleven-week-old fetus. In the past she has carried a baby doll, dressed in infant’s underclothes, nailed to a cross.

The picketers spring into action when the patients begin to arrive, usually around eight-thirty. The Christ for the Nations group is fairly reticent, content to hand out pamphlets and sing hymns. Not so the members of the AAS, who pace the perimeter like anxious sentries. As patients enter the building, they start shouting, begging them not to kill their babies. The protestors have had few successes—AAS members speak often of a topless dancer who moved in with one member instead of going in for her fifth abortion—but most feel, like Jane Wilder, that any baby saved makes their work worthwhile.

Not all of the protestors are anti-abortion. Another regular is Kurt Albach, who drops his mother off at her job at the Routh Street clinic, then parks his car, sips his coffee, and waits to protect women who wander toward the protestors. After so many years of sidewalk duty, he harbors the same cold, intense hatred that seems an occupational hazard here. When Wilder begins talking to a stranger, Albach sidles up swiftly and mutters, “Tell her about all the times you called patients whores, Winston.” The two men may occupy opposite sides of the abortion spectrum, but their anger makes them indistinguishable. In fact, the crowd here has been at it so long that it’s sometimes hard to remember that they are hardened enemies instead of old friends. “God bless you, Kurt,” the Christ for the Nations kids tell him.

One missionary tells me of an anti-abortion video I can rent from religious stores. Narrated by Charlton Heston, it is called The Eclipse of Reason. Baby Jessica has made her way to the sidewalk too. “We freak out over a little girl in a well,” one Christ for the Nations picketer said, “but no one cares about all these babies dying here.” A sunny, hefty fellow named Dan Mosher attacks the sincerity of those who favor legal abortion: grinning smugly, he refreshes my memory on Roe v. Wade—reminding me that the woman who brought the suit had initially claimed she was raped, then recanted.

No feelings are spared here. One of the Routh Street counselors went to high school with Winston Wilder; seeing her head toward the clinic, he reminds her that her husband, MIA in Vietnam, would be ashamed to see her working there. One of the clinic’s security guards is a former employee of Wilder’s. (Both were investigated in the unsolved burning of a Mesquite abortion clinic in 1985.) Wilder shouts epithets at the man and accuses him of being a homosexual.

Just as the conversation on the sidewalk is drifting toward the everyday—Jane Wilder speaks happily of her new grandchild and says, “That’s what marriage is all about. Reproduction”—Lea Braun arrives. “Is that the doctor?” I ask Jane when I see him step out of a silver Porsche around ten-thirty. “You mean the butcher?” she asks me levelly. While Braun strides toward the clinic entrance, the Wilders and a few other members flank the driveway and scream, “Stop slaughtering the innocent!” They are on good behavior today. “Usually they say they’re gonna get my kids or my wife,” Braun tells me. “And they know my kids’ names.”

Taft’s is the only arrival that silences the protestors. “That’s the Queen Bee,” Dan Mosher tells me. Taft studies the picketers idly while moving inside with the purposeful stride of a schoolmarm in a town full of gunslingers. “An admitted lesbian,” Mosher says, once Taft is out of earshot.

The curtain comes down on this performance when all the patients have arrived. Albach is usually gone by ten-thirty, followed by the Christ for the Nations crowd and the Wilders. By noon the clinic belongs to the doctor and his patients, at least until next Saturday, when the fight starts up again, promptly at eight-thirty.

Free From Worry

On the wall of a Routh Street counselor’s office hangs a thank-you note. After her abortion, a woman wrote, “I felt grateful, joyful, whirlingly happy and free. Not free from a dreaded responsibility, for as a partner in a new business I must face and deal with financial and contractual burdens every day. What I felt free from was the worry and the terror . . . the nausea and constipation that had been plaguing me for weeks; free from the resentment and guilt I held toward a future child.” The woman goes on to say that after her abortion, she “was treated to the luxury of dinner out.” Then she went home and baked cookies. “Later, as we pulled the covers over us and I accepted a cuddling embrace, my love said, ‘It’s just the two of us,’ and I knew he was happy too.”

Tucked behind a sofa in a room nearby is a poster the clinic is holding in reserve. It shows a photograph of a nude woman, dead on the floor of a bleak, empty room. Her buttocks are to the camera in a lurid, police-blotter style; there is blood on the towels bunched between her legs. She has died from an illegal abortion.

Between the lives of these two women lie sixteen years of social change. Those who oppose legal abortions like to say that 90 percent of all abortions are for purposes of convenience, and I imagine that the author of the above letter is just the kind of person they have in mind. Her blitheness makes me angry; I wish her independence had meant so much to her that she could have been extra careful with her birth control. Still, I believe that the only thing worse than this woman having an abortion is that she be forced to bear a child—unloved and unwanted—against her will. I know too that abortion will always be with us and that if it is outlawed again, the author of the letter could easily become the woman in the picture. My time on the front lines left me certain of one thing, though: We have forgotten that there is a profound difference between preventing a pregnancy and ending one.

The fight over abortion is so emotional that it’s easy to forget a simple truth: in many cases it’s preventable. It’s also easy to forget that abortion is part of the larger problem of all unplanned pregnancies—a category that includes half of all pregnancies in the United States. But as long as our attention is focused on the abortion battle, no one has to confront the reason why there are so many abortions—1.5 million a year. This way, we can condone rampant sexuality in our culture while we neglect to send a corresponding message that men and women are responsible for their sexual behavior. This way, we don’t have to worry that drug companies aren’t developing more effective birth control methods (there are fewer methods on the market now than there were five years ago). This way, those who oppose legal abortions don’t have to confront their broader opposition to the modern world—to sex education, to birth control in any form, to values different from their own. It’s a final irony that the people who run clinics like Routh Street are among the few trying to stem the tide.

- More About:

- Politics & Policy

- TM Classics

- Abortion

- Dallas