This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

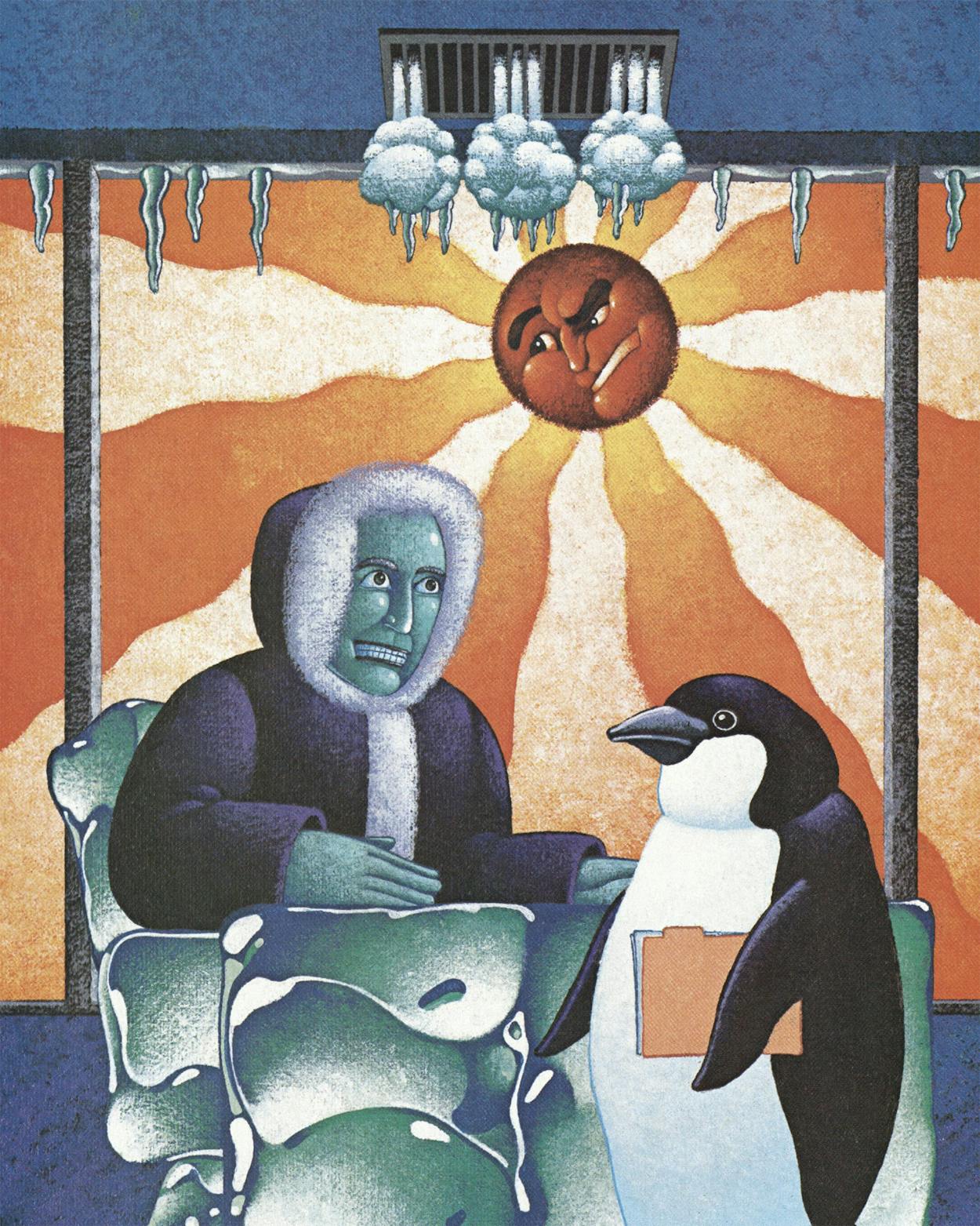

I don’t like the heat, but I hate the cold. During the winter, some 17 million other Texans agree with me. From April till October they change their tune, and I am a lone voice crying out in the icy vaults of bank towers and the arctic mazes of shopping malls. I will take the sweat; you can have the goose bumps. Each year I observe many Texans scurrying around outside on the coldest day in January without coats or even jackets. They are the same people who wear sweaters to the office in August. They are nuts.

I admit that air conditioning aids in the performance of certain mental functions associated with earning a living. Hence, I have spent many years of my life chilled to the requisite temperature to do my job. Cold air, however, is not necessary for the simple enjoyment of life. Consequently, nothing has ever seemed more liberating to me—or more my birthright as a modern Texan—than exiting the revolving door of a downtown high rise on a summer evening and being baptized by a blast of hot air.

Now the day can begin in earnest. I can walk on the sweltering side of the street until my bones warm up. Then I can cross over to the shady side. I can marvel at the air that is hot enough to bake a pizza escaping from my locked car. I can curse my blistering steering wheel. I can go somewhere and exert myself, then drink an ice-cold beer. Or I can not exert myself and drink an ice-cold beer. I can get hot lying on the ground, then jump in some cold water.

Countless other Texans join me in those after-work activities, but they are only dabbling. Now comes the hour of reckoning. As they drive to the centrally air-conditioned houses that approximate the frigid workplaces they have occupied all day, I head for a home equipped with a lot of open windows and ceiling fans. The two window air conditioners, which I do not deny owning, are reserved for company and execrable situations, such as the summer of 1980.

This is what I don’t like about central air: the heaving rumble of the compressor, the hiss of forced air, the dead quiet once the house attains the ambience of a mortuary, and the utility bill at the end of the month. The secret that is lost to people addicted to air conditioning is that most summer nights range from tolerable to wonderful. The fierce afternoon winds down to placid night complete with a breeze that when shoved around by a ceiling fan is all a body in repose requires. And then there is morning: No matter how high the temperature will peak later in the day, the early morning hours have a cryptic, confiding coolness, the discovery of which is as pleasant as drifting into a cold current of lake water.

I don’t object to comfort. It’s just that central air has always seemed like such a radical way to achieve it. The ceiling fan has made a welcome comeback, but whatever happened to the evaporative cooler and the attic fan? Those two pieces of equipment, which respectively cooled me through a childhood in West Texas and an adolescence in Dallas, had several admirable traits. The evaporative cooler, by blowing air through a wet filter, created the kind of deep cool one associates with caves. The attic fan possessed the miraculous ability of creating a breeze where none existed. Households with those devices did not have to be hermetically sealed from the rest of the world.

The hermetic seal brings me to the subject of air-conditioned cars, which I have always found to be as claustrophobic as centrally air-conditioned houses. For years I claimed I would never own one. Then two things happened. I acquired a dog that loved to ride around in the car with me but couldn’t take the heat, and I learned at considerable expense that unair-conditioned cars have no resale value in Texas. So I bought the dog an air-conditioned car, and in the process I came to see that my new acquisition allowed me to arrive at certain social events in a state of composure previously unknown to me. I am not so hawkish on air-conditioned cars anymore. Still, I hesitate to let summer pass by behind glass. Earlier tonight, for example, while driving along some backcountry roads, I achieved what I consider to be a state of climatic perfection. I watched the sun set on a particularly virulent day, my cheeks cooled by drafts from the air conditioner but my windows rolled down to enjoy the emerging summer night.

I concede that there are many objectionable things about the heat. There are, for example, two or three nights in any given summer when it is all but impossible to sleep without air conditioning. I attempt to do so, and I am usually the worse for wear. I acknowledge that preparing meals in an unair-conditioned kitchen has its problems and that my solution to the dilemma —cooking in the back yard on a Coleman stove—will appeal to few people. And I confess that the older I get, the more the heat bothers me. But the solace in being old and hot is that it is still better than being old and cold.

- More About:

- TM Classics