If Rangerettes ruled the world, there’d be so much discipline,” said Lory Lyon, who was on the lower bunk bed in a dorm room at Kilgore College.

“And respect,” added her friend Morgan Duplant, sitting cross-legged on the upper bunk. “The words ‘slut’ and ‘ho’ would not exist.”

“It’d be happy—so joyous,” Lory said. “There’d be motivation to be a better person.”

As I sat on the floor talking with Lory and Morgan, another girl walked into the room and joined the conversation. “Women would be more ladylike, wearing closed-toe shoes and tights,” she said. “And they’d sit properly in public.” The girls all nodded in agreement.

Although some might consider the Kilgore Rangerettes an anachronism, dozens of fresh-faced teens from across the state flock to this East Texas junior college every summer to try out for the drill team. Most of them have already been accepted at the school, but some will apply only if they make the squad. This year Lory, who is from Longview, and Morgan, from Beaumont, were among the 78 girls from small towns and big cities who competed for thirty or so coveted spots on the high-kicking squad. Both girls are nineteen-year-old sophomores, with perfect, tanned skin and smooth brown hair. Lory says that Morgan looks like a flamingo, on account of her long, thin limbs; Morgan says that, with her tiny nose and big, round eyes, Lory looks like Cindy Lou Who.

Lory and Morgan had been practicing their kicking and dancing all summer, but they had dreamed of being Rangerettes practically forever: “Since I was three,” they told me in unison. Morgan heard about the group from her mother, who was on the team in the mid-seventies. Lory heard about them from her aunt and her great-aunt, who were both Rangerettes—”Plus my brother was a manager for three years,” she said proudly. In high school, Morgan was a cheerleader and a drama student and Lory was on the drill team. Though both had gone to Rangerette summer camp for years, they didn’t become friends until last year, when they bonded during the tryouts. When they weren’t chosen, they refused to let it get them down, for that is not the Rangerette way. Within seconds of wiping their tears, they decided to go ahead and attend the college, live together that fall in one of the dorms, take dance classes from the Rangerette choreographer, make friends with the Rangerettes, and try out again the next year.

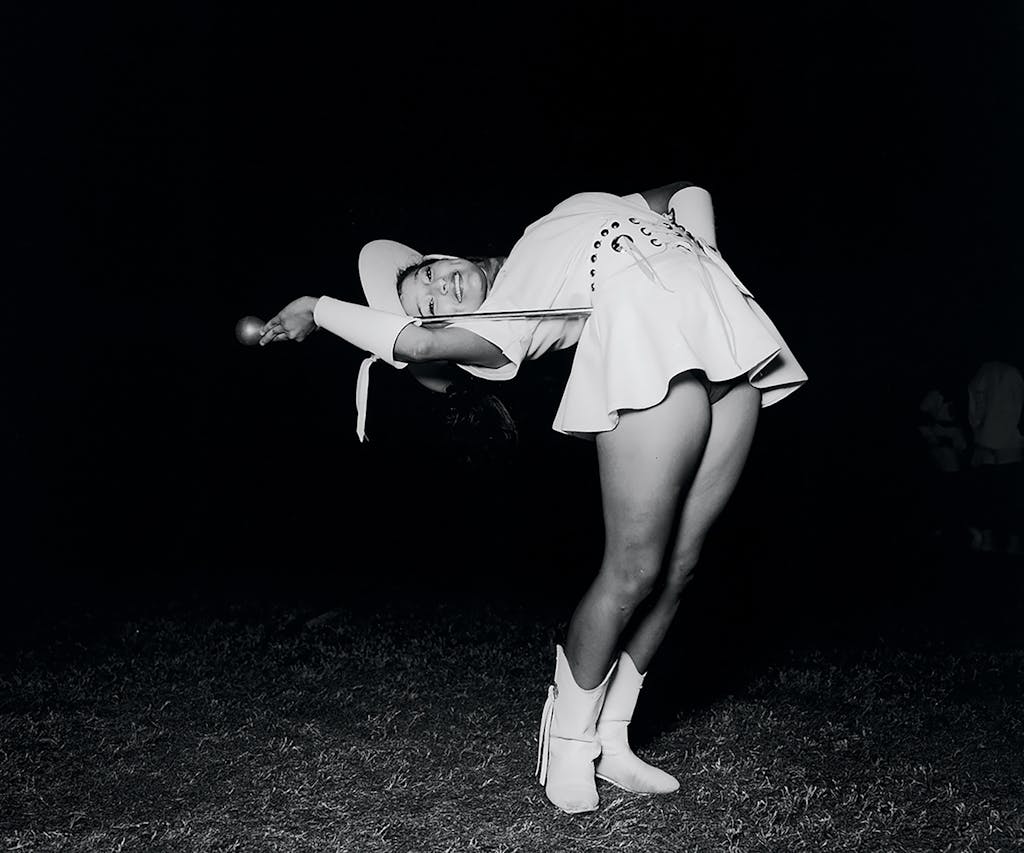

Ever since oil was discovered in Kilgore, the town has produced only one other export: the Rangerettes. As all of them will tell you, they are much more than a precision drill team (although they invented the dancing drill team concept in 1940, thank you very much). “We have drill teams because of the Rangerettes,” Morgan told me. “They have had only three directors, and the uniforms have never changed, and, like, omigod.” To the outside world, the group is known for its seemingly effortless hat-brim-touching high kick, which has been performed as far away as Hong Kong and as nearby as the grand opening of the local Brookshire Brothers grocery store. But to the Rangerettes themselves, the organization is more of a military-style finishing school for girls with strong morals, a positive outlook, and the discipline of a drill sergeant. “What scares me is we’re picking the future members who will carry on the traditions,” a sophomore Rangerette told me. “They will be the ones passing this on.”

On Monday morning of the last week in July, Lory, Morgan, and two other hopefuls were sitting around a table in the Kilgore College cafeteria, eating bowls of Cocoa Puffs and reciting the rules they had been given the night before. They were required to wear their hair in a ponytail on top of their heads. They were not allowed to wear makeup except for red lipstick. They had to pin a gigantic name tag on their solid-colored leotards. They could not wear jewelry, needless to say. Unless given permission to speak, they had to answer all questions from their assigned advisers and other sophomore Rangerettes with only “Yes, ma’am. Thank you, Miss Jones [or whatever].” The girls eyed one another across the table, cracking up at their goofy-looking hair fountains and bright-red lip gloss. There were reasons for these rules. “Many girls need to come to a more humble place,” director Dana Blair told me. “They have always been the officer and won everything and been the ‘it’ girl, and if we had all those egos running around, practice would be difficult.”

So far, the tryouts were similar in many ways to last year’s, Morgan said, chewing her cereal, “only this year it’s weird because the sophomores are all our friends.” But even though that was true—they had all lived in the same dorm as freshmen—Lory and Morgan were pretty well excluded from the Rangerette fun. The girls have a saying about the organization: “You can’t understand it from the outside, and you can’t explain it from the inside,” and last year Lory and Morgan might as well have been in Alaska.

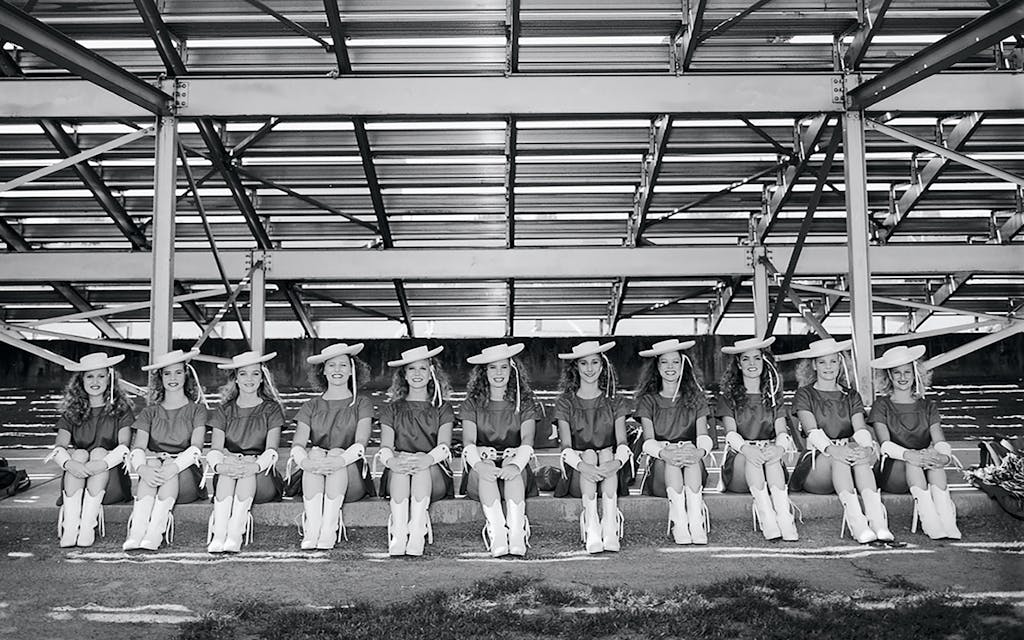

I walked over to a table of sophomore Rangerettes. A group of a dozen or so stopped talking and looked up at me suspiciously when I asked to sit down. They were all wearing matching baseball shirts with “Rettes” printed on the front and their last names on the back. Their sporty accessories were perfectly color-coordinated, from mod tennies to glittery barrettes. On this particular day, the theme was red, white, and navy blue. The girls live together in the same dorm, eat together, and practice together, leaving one another only on weekends, when they drive back to their hometowns because there isn’t much to do in Kilgore, a town of 12,000. But wherever they go, they are, first and foremost, Rangerettes. “We’re really big on reputation,” Hillary Hoffman told me. She and her sisters, Hayley and Cali, who are from Coppell, have the distinction of being the drill team’s first triplets. “When you get together at a party, you’re still representing the Rangerettes.”

Pushing aside her food tray, a sophomore with curly brown hair said that she was having to adjust to her new status as a second-year Rangerette. A freshman, she explained, is constantly bossed around by the sophomores, so that by the time she graduates, she has thoroughly experienced the roles of follower and leader. “It will be weird that the hopefuls can’t talk to us from now on,” she said, rising from her chair to head to morning practice. “And when we walk into the gym, they all have to greet us by our last names.”

A few minutes later, I witnessed that surreal tradition. As the Rangerettes filed into the gym, the hopefuls stopped stretching and beamed panicked, exaggerated smiles at them while raising their right hands high into the air, fingers spread. “Hello, Miss Satterwhite!” they yelled. “Hello, Miss Oden!” “Hello, Miss Coker!” If several sophomores walked in simultaneously, the girls screamed their rapid-fire, unintelligible greetings like superfriendly traders on the floor of the stock exchange.

If the scene sounds mortifying, keep in mind that none of these girls are shy. Several former Rangerettes have gone on to careers in entertainment, as noted by their alumnae organization, Rangerettes Forever, which also funds many of the girls’ scholarships. Alice Lon, for example, the longtime Champagne Lady on the Lawrence Welk Show, was a Rangerette. Six of the 38 current Dallas Cowboys Cheerleaders are former Rangerettes. And while most of the sophomores I spoke with planned on finishing their degrees at a four-year university and working as accountants, physician’s assistants, schoolteachers, and the like, about a quarter of them wanted to become drill team instructors, spreading the word about the Rangerettes so that other girls can grow up like Lory and Morgan, never remembering a time when they didn’t know about the organization.

By Monday night, five days before the final results would be announced, nerves had already begun to fray. But grace under pressure is a Rangerette tradition: The group’s slogan is “Beauty knows no pain.” I had heard stories of girls who kept smiling even after kicking so high they bloodied their noses. I’d heard how Gussie Nell Davis, the Rangerettes’ revered and beloved founder—who was never seen wearing anything but stylish suits and four-inch heels—once stomped up to a girl who had fainted on the field and yelled, “I have no time for this! Get up!” That evening, when director Blair announced a surprise evaluation of the dance routine the hopefuls had learned on Sunday, word was out that one stressed-out girl had already packed up and left. Morgan’s group of four nailed every move, while Lory’s group struggled, panicking in the middle of the routine until one of them remembered a key jump. Throughout the evaluation, however, the girls’ expressions remained determinedly cheerful as they strutted and leaped across the floor. Even the one who had mono. Even the one who had slipped and fallen on her behind. Even the one who had thrown up in the middle of the routine.

“All the hard stuff is done,” Morgan said on Thursday night. After being weighed in on Sunday, each hopeful had sat down for an interview, during which many of them were asked to describe the ultimate all-American girl (although Lory was asked the more existential question “What makes you Lory?”). On Monday they had suffered through Model Night, when each of them, wearing only a leotard, had to exhibit poise by striding onto an empty stage, turning around to show off her figure, then walking up to a microphone and announcing her name, hometown, and proudest achievement. (The answers ranged from “raising a prize goat” to “organizing an education program for needy children in Indonesia.”) On Tuesday night they had sat on the gym floor and eaten pizza while former Rangerettes, some in their seventies, told stories about Gussie Nell Davis, who had once boasted, “By the time I was through with [my girls], they were scared to death to act like heathens.” The hopefuls cried when one speaker said that learning a Rangerette’s discipline and optimism and perfectionism had guided many women through hard times, “even if it was difficult to understand that not everybody strives for perfection, such as a spouse who is not nearly as ever-so-perfect as you.”

At the talent show on Wednesday, Morgan and Lory had performed a jazz routine, which they had paid twin former Rangerettes in Houston $400 to choreograph for them. “It was okay,” Lory said, hesitantly. “It was good. Except my adviser said that I kept looking at the ground while I was dancing.” Despite her usual optimism, Lory was beginning to seem nervous about her chances. Later that night, in the dorm room, Morgan took a bite out of a peanut butter sandwich and said, “My adviser is so awesome. I love her. She tells me what to do so I can fix it, and she said I’ve been fixing all these little things.” Lory, who was munching on Cheese Nips, just stared blankly at the wall.

One day Morgan told me that her friends from high school thought she was crazy for wanting to be a Rangerette. “You don’t understand,” she said she told them. “It’s tradition.” When I mentioned that prancing about in miniskirts and white hats and white boots would be ridiculed in some places these days, she and a few other girls looked baffled. They figure that if someone doesn’t understand why they would want to spend their first two years of parentless freedom in the Rangerettes, then that person must have never felt the thrill of being in a world-class drill team and is to be pitied. Besides, Morgan and Lory and the other hopefuls had made their pilgrimage to this little town for a bigger purpose: to become ambassadors for a disappearing way of life. It is a role that clearly strikes a chord. Watching the Rangerettes perform to the school’s fight song, a college staffer told me, is an experience so powerful “it will make your hair stand on end.”

On Thursday night, before the next day’s final tryouts, the hopefuls filed into the auditorium for a “special presentation.” Dana Blair walked onstage in front of the silent, ponytailed girls with their perma-grins and said, “You can stop smiling.”

“Yes, ma’am. Thank you, Mrs. Blair,” they said in unison. Blair announced that there was a special surprise, something that would remind them of why they had been working so hard. A drum roll sounded over the loudspeakers, then, as “The Rangers’ Song” played, the Rangerettes marched onto the stage. “I thought I was sobbing,” Morgan told me later, “then I looked at Lory.”

“Sobbing,” Lory said.

The hopefuls watched the Rangerettes that night with a heartbreaking eagerness to please, their smiles so fixed their faces twitched. Some of the girls had no backup plan if they didn’t make the cut. One of them looked shocked when I asked what she would do if she didn’t make it. “Go home, I guess,” she said. Lory and Morgan assured me that they would be all right if neither of them made it; Lory would go on to teach elementary school and Morgan would be a Broadway star. But it would not be cool at all if one made it and the other didn’t. Explained Morgan, “We wouldn’t be on the same level anymore.”

Earlier in the summer, I had asked Morgan and Lory to describe what the tryout week’s finale is like. “So they bring us all into this auditorium and it’s this big thing, right?” Morgan said. “And they bring us all on the stage and we sit down and we’re all holding hands and shaking and we’re already crying, right?”

“Waaay in advance,” Lory said.

“And the Rangerettes are standing there in a line in their uniforms.”

“Crying.”

“Bawling-crying, because they know who didn’t make it,” Morgan explained. “And we’re crying, and a couple of people say some things, you know, about how everything happens for a reason.”

“Blah, blah, blah,” said Lory.

“And then finally Mrs. Blair tells us all to bow our heads and say a prayer.” Morgan looked at Lory and they each took a deep breath as they relived the moment. “And then a sign drops down”—a board listing the tryout numbers of the new Rangerettes—”and it’s chaos, with girls screamin’ and runnin’ and jumpin’.”

On Saturday morning at ten, judgment day had finally arrived. No guests were allowed in the building until after the announcement, so the tortured parents waited outside. Inside the auditorium, the line of Rangerettes stood onstage, as stiff as their hats. Their lips trembled and their wet eyes looked far off into the balcony as the hopefuls silently filed in and sat cross-legged on the stage floor in front of them. Lory was far less confident about the outcome than Morgan. At the final tryouts the day before, her foursome had slipped up again and forgotten a good portion of its third routine, to “Son of a Preacher Man.” With so much disarray in the group, she had had a tough time remembering the steps. Afterward she had walked proudly off the gym floor, but in the waiting room had collapsed into a pile next to Morgan. Inconsolable, her face red, her lashes and lips blurry with tears, she had held her head between her knees for a long time.

The hopefuls watched the Rangerettes with a heartbreaking eagerness to please, their smiles so fixed their faces twitched.

Now it was the moment of truth. Blair stood before the hopefuls and began The Speech. She encouraged the ones who didn’t make it to not give up on their dreams, recounting the morning’s news report of a surfer who, although she’d lost an arm to a shark attack, was still surfing. The group sniffed and brushed away tears and prayed. Lory was sitting between Morgan and me, and she grabbed our hands and squeezed. Then a Rangerette read a poem called “Freshman Hopeful,” and all around us chests heaved as girls sobbed and sweated.

When the sign was lowered, the room fell silent as the girls searched for their numbers. Then everyone let out a high-pitched scream, as if a winning free throw and a car crash had just occurred simultaneously. Lory and Morgan had both made it.

Meanwhile, the anxious parents waiting outside attempted to identify the shrieks inside. There were 45 girls whose numbers had not appeared on the sign. Some of them hurried through the lobby to the parking lot, their parents hovering silently at their sides. Others lay paralyzed on the stage floor until their moms and dads helped them to their feet and smoothed their hair, hugging them and trying to remove them from the scene gracefully.

Finally, the only ones left were the 2004–2006 Rangerettes. Linking arms and yelling out the drum roll—”Da da! Da da! Daaaaaaa, da da!”—the sophomores surrounded the new members, who stood straight, their faces contorted with pride and emotion. As the group began to sing “The Rangers’ Song,” most of the new Rangerettes were quiet. But Morgan and Lory sang along, because they knew the words.