In your own illustrious past, perhaps you logged some time with a rock and roll band. Maybe you still do. If, like me, you squandered a chunk of your misspent youth on such endeavors, you remember the nights on the floor, the crappy food, the endless cramped drives, and your companions’ fluctuating states of hygiene. It’s a netherworld existence that tests the idealism of would-be stars—and it’s a hell of a lot of fun. Yet unless you were lucky enough to be among the .001 percent rewarded with R.E.M.-like success, you probably called it quits after a few years. Or months. So why is a punk band with a preposterous name like the “Butthole Surfers” still at it after two decades?

“I totally foresaw it,” deadpans Gibby Haynes, the Surfers’ vocalist. “I’m going to do this for twenty years.” Did they ever. No one ramped the hilarity, desperate poverty, and drug-fueled absurdities of the road to such heights. “You either die or succeed,” guitarist Paul Leary explains, “and I really thought we were going to die.” Haynes, the son of Dallas’ famed children’s-television host Mr. Peppermint, was a basketball star and a finance major at San Antonio’s Trinity University, where he met Leary. They formed the band in 1981, and for a while Haynes was balancing punk rock with a job at the accounting firm of Peat Marwick Mitchell. (“I was legendary there,” he says. “I’m sure they still hold my work up for ridicule.”) Day jobs quickly gave way. The Surfers traveled in a Nova with a sawed-out back seat, lived as nomads, released a string of bizarre recordings, and according to drummer King Coffey, who joined the band in 1983, “hung close to Gibby because he was carrying the cash.” Onstage they were at once intense, funny, and frightening. Haynes, wearing underwear (if that), would prowl the stage, douse cymbals with lighter fluid and set them afire, rip dummies to shreds, and bellow through a megaphone over a caterwaul of guitars and tribal drums. Strobes flashed, smoke billowed, and grotesque medical films were projected on top of the band. This was not just a show; this was like standing in the middle of Apocalypse Now.

It took time, but the rock world finally caught up to these madmen. In 1996 the Surfers released Electriclarryland on Capitol Records and scored a bona fide radio hit, the amiable trip-hop novelty “Pepper.” After five years of silence, their latest album, Weird Revolution, came out on Disney’s Hollywood Records in August. If it’s strange to see Disney releasing a Butthole Surfers album, it’s stranger still that the album’s first single, “Shame of Life,” was co-written by multiplatinum metal rapper Kid Rock.

What? The twisted creators of “Bar-B-Q Pope” collaborating with an MTV star? According to Haynes, Kid Rock wanted to use a sample from the Surfers’ Black Sabbath parody “Sweat Loaf.” “We were like, ‘Oh, Kid Rock, ka-ching, sure,'” Haynes says. As a swap, he asked Kid Rock for help with the chorus of their planned single. “He came to my house in his big white limousine with his five-hundred-pound bodyguards. He says, ‘Let’s just write a new song,’ and I’m like, ‘Uh, okay.'”

In record time Kid Rock is singing “I love the girls and the money and the shame of life.” “We were all kind of like, ‘Yeah, way to go, Kid,'” recalls Coffey. “I mean, you can’t really slag him for writing it there on the spot. And how do you tell a guy who’s doing this out of charity that it’s so, so, what’s the word . . . bad?”

Haynes was genuinely charmed yet admits, “It took me a long time to do the verses because it’s hard to embrace a song that says ‘I love the girls and the money and the shame of life.’ It’s tough.”

But embrace it they have. “Shame of Life” is attracting sizable radio interest. So this punk band has a new pop attitude, and more than a bit of an identity crisis. Does this make them sellouts? Maybe. The funny thing is, they’re okay with that. It was the band members who decided that their long-delayed album was missing a hit along the lines of “Pepper,” and their producer, Rob Cavallo, found their willingness to make a more commercial record refreshing. “A lot of young bands can be really precious about a lot of stuff that doesn’t matter,” he says. “The Surfers don’t have those problems.”

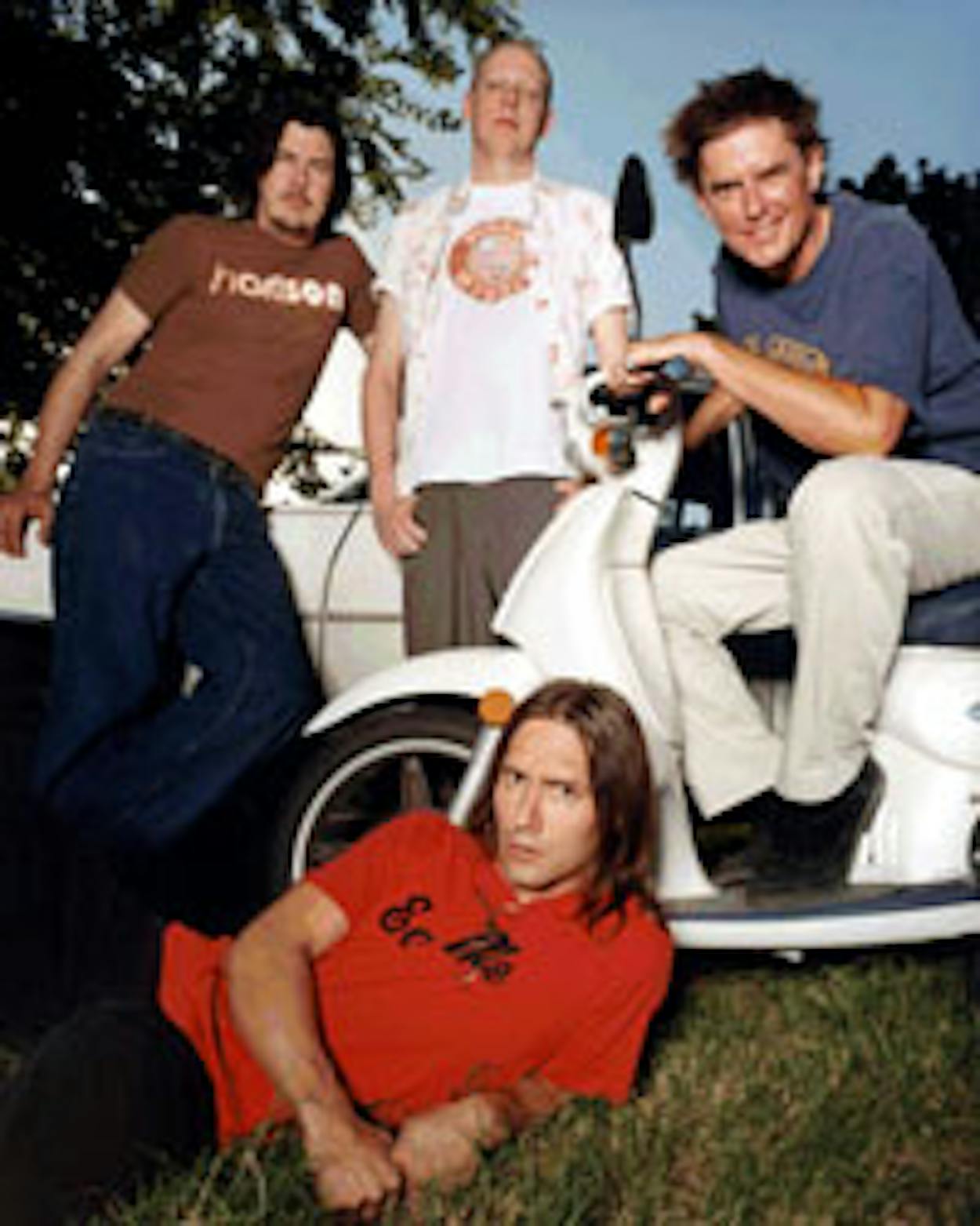

The inference here being that this is not a young band. Haynes and Leary are 44, and Coffey is 37. “It’s not really a band anymore,” says Coffey. “It’s like family.” A dysfunctional one, though, that has included a changing lineup of bassists and, for a time, Slacker poster girl Teresa Taylor on drums.

The fact that it took the Butthole Surfers so long to turn the corner didn’t help that dysfunction. When they should have been enjoying the success that “Pepper” brought, everything ground to a halt. “We spent a great deal of time being digested through the bowels of the music industry,” says Leary with the group’s trademark scatological fondness.

In the early nineties, more than five years pre-“Pepper,” the road-weary band had settled in Austin. Armed with a new manager, Tom Bunch, they embarked on the cushy 1991 Lollapalooza tour, with roadies setting up their gear and labels knocking on their dressing room door. Hale Milgrim, then the president of Capitol Records, signed the Butthole Surfers for the impressive sum of $300,000 an album.

Their first Capitol album, 1993’s Independent Worm Saloon, topped out at around 300,000 copies. Movie soundtracks and even a Nintendo commercial followed. Money was flowing, but all was not well. Haynes didn’t stop the Lollapalooza party when the tour ended, and he began a battle with drug addiction. He would enter rehab twice before the band was able to finish the sessions for Electriclarryland. Once “Pepper” began to click, even the Butthole Surfers (or, as they were known at Wal-Mart, the B***h*** Surfers) had become a household name.

With catalog sales on the rise, the band, through Bunch, approached Corey Rusk, an old friend who had released four of their albums on his label Touch and Go. The Surfers wanted to negotiate a better deal for the royalties on those releases; Rusk, who had supported the band in their pivotal days, insisted their old handshake deal was intended for perpetuity. Both sides dug in. The Surfers prevailed in a bitter court battle, lost a friend, gained some cracks in their “cool” credentials, and set a precedent Leary says will help other bands. But the wounds have not healed. Coffey said that seeing his name attached to the lawsuit was “the worst I ever felt in my entire life.”

It got worse. Electriclarryland had sold around 800,000 copies, and the pressure was on for a follow-up. Yet Haynes began slipping back into his old habits, disappearing for weeks on end. It took two years for the band to finish what was to be their next Capitol album. The Last Astronaut was finally presented to the label. Nothing happened.

With Capitol’s president, Gary Gersh, on his way out, Bunch believed it was foolhardy to stay with the label and says he had lined up other options. The band, in turn, had a falling-out with Bunch. Accusations flew on both sides, but no matter whom you believe, it’s clear no one was communicating. And the new album languished. Bunch sued for payment, the group countered, and all concerned finally met for mediation earlier this year. The band says a settlement is near, but Bunch says he’s showing up for an October 1 court date. So it ain’t over yet.

In the meantime, the Butthole Surfers spent the past three years tinkering with what became Weird Revolution, writing new songs, and finding a new label and new management. And healing. Haynes says he’s doing very well these days, thank you. Though the band hasn’t played onstage since 1996, they’re once again hauling out the strobe lights, dancers, and lighter fluid. But will this year’s model equal the Armageddon of the early days? “Oh, yeah,” says Haynes. (“I hope not,” says Leary.) Haynes jokes that he feels sorry for people who worry about what “Gibby’s going to do when he turns sixty,” but as the band faces the all-too-familiar past, the future is clearly on all their minds. “We never planned anything in our entire career,” says Leary. “We would just wake up and do what we did.”

By the guitarist’s own admission, the band set out to make the “stupidest records ever”; now it all seems so purposeful. Is this a band on life support? You can’t really blame them for trying. They looked desperation in the eye for so many years, yet today there are mortgages to pay. “Shame of Life” could prove to be another “Pepper” or beyond. Or it could vanish within weeks without a trace. Either way, eventually these once and future punks are going to have to face the question they have successfully dodged for two decades: What happens next?