Most western artists play up the majesty of wide-open plains or soaring mountains. Wayne Baize strives for something different. His drawings and paintings typically offer modest portraits of animals, often surrounded by a mere suggestion of location. A Hereford calf, a pinto donkey, or a mare and colt might be framed by nothing more than a sprig of grama grass or a Spanish dagger. Even when the environment determines the composition—a scene of horses watering at a stock pond, for instance—the edges usually fade into the ether. His subjects seem to step out of a dream or a memory, speaking to viewers who once lived the ranching life, or still do, or wish they could have.

Baize is less a teller of stories than a ponderer of moments. Although he has witnessed and photographed bucking horses and out-of-control livestock involved in wild wrecks, he doesn’t paint them. His fascination is with the exchange of a glance between animal and human, or the way two animals shoulder each other, or a horse’s muscling and structure. The subject of his 1981 acrylic and colored-pencil portrait Spring is an alert, bright-eyed calf, with long white eyelashes and a coat that’s a deep mahogany red, clean, fluffy, well licked, well fed, and perfectly proportioned. The drawing could be set anywhere or nowhere (heaven, maybe?), except that behind the calf, we can see a West Texas cholla—covered, of course, with idealized thorns and fuchsia blossoms, no grasshopper bites or shriveled segments in sight. The calf itself, radiating intense confidence, is already hustling up some grazing and taking the pressure off mama.

There’s a certain amount of romanticization going on here and in most of Baize’s work. When a roped animal in one of his drawings is in a state of panic, the hands on the rope are in complete control. Of course, ranch life is seldom quite so perfect. Some years no rain falls, a hard freeze bursts miles of pipeline, or a calf’s mother develops cancer eye. But it’s difficult to paint, photograph, or write about cowboys without romanticizing. Perhaps only outlaw country music has come close to revealing the darker side of cowboy life—the cheating, drinking, and broken dreams.

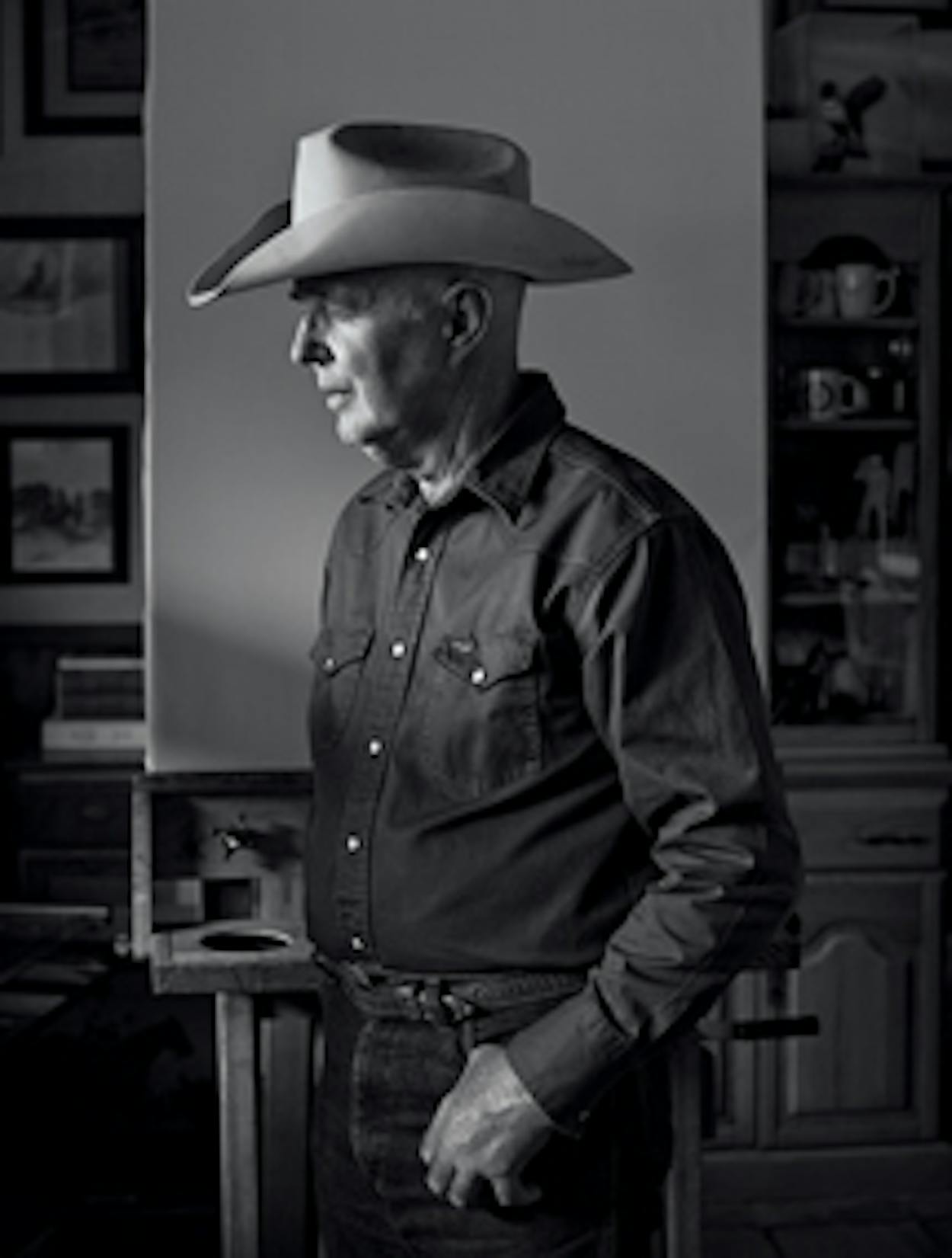

“My art may be romanticized, but it has a grain of truth to it,” Baize says, sitting in his studio near Fort Davis. “It seems like the ongoing philosophy of the day is that the government needs to take care of you. And you’re entitled to it! Money is the ultimate goal in life. And then you look at the cowboy. The climate is sometimes harsh and unreliable, and success often depends upon persistence. The job doesn’t pay much, but the life that he lives and the pleasure that he gets out of God’s creation are enough. He recognizes the beauty and the blessings that can’t be bought with money and the freedom that you have when you take self-responsibility. When you don’t take responsibility, you don’t have freedom.

“To me the cowboy is nearly America personified, the part of America that I think has been so important in the development of our country. People who came west, they didn’t have any guarantees of success, just freedom. I guess what I hope my art would convey is the importance of the West, the lifestyle that we all love, and the part that the people in the livestock industry have played in making this country what it is.”

Baize, a fourth-generation Texan, is himself a product of that America. He was born in Stamford in 1943, the son of a stock farmer who enjoyed plowing with mules but didn’t like working the land so much after tractors came in. The family lived an hour or so north of Abilene and tried to grow cotton and maize during the fifties drought. Baize doesn’t remember them ever managing to produce a good crop.

When Baize was twelve, he asked to take art lessons as a Christmas gift. “Mother said a coloring book was one of my favorite . . . toys, I guess you’d call it,” he says. “Drawing just always fascinated me, and of course I certainly didn’t know you could make a living at it.”

His interest was always in Western subjects, so his teacher, Sarah McDonald, showed him sketches that Frank Tenney Johnson, the great “Master of Moonlight” artist who often visited the nearby SMS ranches, had done for her. Baize was fascinated by Johnson’s method of tagging along with cowboys and the quiet feel of his studies. McDonald also introduced him to the work of probably the most famous Western artist of all time, Charles M. Russell. Baize was awed by Russell’s magnificent use of color and his ability to evoke action in a single frozen moment. Under McDonald’s guidance, Baize started with charcoal drawings and progressed into oils, but he preferred the refinement that pencils gave him.

Eventually the Baize family sold their land and moved to a stock farm south of Abilene near Potosi, where Baize took lessons from Gene Swinson, a humble local art teacher who lived in Baird. (Swinson had a talent for sparking a deep interest in art; another of his former students is now the creative director of this magazine.)

“This was in the early sixties,” explains Baize. “Western art was enjoying a renaissance, and the artists were establishing reputations in fine art. The Cowboy Artists of America organized in 1965. It seemed like I was at the right place at the right time. It amazes me.”

Baize was also developing his own cowboy and horsemanship skills. “After I got out of high school, I helped my older brother Paige on the weekends, ranching and cowboying, farming, driving a tractor. I also worked in a feed store and lumberyard, but I had always envisioned a future working the land.” Later the family moved to Baird, where Baize and his brother Arlon began raising horses from the Doc Bar bloodline.

In the mid-sixties Baize caught a break when Gary Luskey, of Luskey’s Western Store in Abilene, let him set up a table. “Customers would bring in photographs of themselves or their horses, and I would do portraits, mostly vignettes, but sometimes with backgrounds when people wanted their own ranch or their own scenery,” Baize recalls. Soon he began making a name for himself in the world of ranching periodicals. He did a portrait of a cutting horse that ran on the cover of the American Quarter Horse Journal and a drawing of a Santa Gertrudis bull that graced the cover of The Cattleman. Illustrations for Western Horseman followed.

A chance encounter a few years later with the esteemed Western artist Tom Ryan, at a stock show in Fort Worth, was a turning point. Baize, with encouragement from his brother, walked up to Ryan and introduced himself. Ryan invited him to bring some of his work to Lubbock sometime. Baize took him up on the offer and made a lifelong friend. “He talked to me about edges. I remember one time I had this drawing, and he said my edges were too hard, and he just took his thumb and smeared it. Just . . . tcht! He said, ‘Does that bother you?’ I said, ‘Yes.’ He said, ‘Well, get used to it.’ I owe so much to him. He suggested that I go into colored pencils. So I started putting color into some of my drawings.”

Through Ryan, Baize met other cowboy artists, like Charlie Dye and R. Brownell McGrew, and in the early seventies Ryan invited his apprentice to try selling his work at the OS Ranch show in Post. Baize became a regular, selling out his work every time. He soon got offers to display his work at galleries in Dallas and Scottsdale, Arizona, and had his first one-man show in Stephenville. “That’s when I quit going to Luskey’s and started drawing full-time,” he says. Since then he’s made his living as an artist, working in pencil, colored pencil, mixed media, and oil. In 1995 he was invited to join the Cowboy Artists of America, and he served as its president in 2007. In 2000 he was named Artist of the Year by the Academy of Western Artists. He has been featured in both Livestock Weekly and Southwest Art, publications whose subjects rarely overlap.

As he has for three decades, Baize works out of his home on the ranch where he and his wife, Ellen, raised four children and plenty of livestock. His studio, just off the living room, has a large picture window facing north and is surrounded by scenes that inspire him. Outside, Wayne Baize’s Hereford cattle and horses strike Wayne Baize poses as they graze the Davis Mountain pastures. Inside, on his studio walls, are five small original Tom Ryan drawings, a lithograph of Ryan’s Passing By, a Ryan print titled The Impressionable Years, and more than a dozen pieces by a handful of other Western artists. Files containing thousands of photos that Baize himself has taken are stored within easy reach.

Throughout his career, Baize has carried a camera with him when he gathers material for his drawings and paintings. Because he’s a skilled cowboy, he notices moments shaping up and can anticipate potential shots. While most Western artists render authentic-looking cowboy hats and saddles, Baize aims for something that only a knowing eye will catch: a horse’s shoulder in the right spot to turn a cow, perhaps, or the posture of a cowboy leading a remuda as he moves to slow the pace. Photographing those scenes helps Baize remember things that his imagination might not be able to reproduce. Although it may seem like he’s snapping away and hoping to get lucky, every photo captures a particular expression, posture, or composition.

Surprisingly, he thinks his photography will someday be regarded as more important than his art. “The older I get the more sentimental I become, and these photographs have come to mean more to me than just material for a painting,” he says. “In the paintings we probably do romanticize it a little bit. In the photograph the crease might not have been just right or their shirt may not have been ironed. It’s just the way it was.”

Baize believes photography does have its drawbacks, though. “In my photos, most of the time the color is not as good as I remembered,” he says. “Things can get distorted, and the edges are usually too hard or harsh, the shadows usually too dark. The photo can give you too much information. You need to learn to simplify the patterns and leave out details. For example, I don’t have too many fences in my paintings. I prefer that the cowboys and cattle and horses not be fenced in.”

As always, Baize chooses to keep his focus on the four-legged creatures or the instant of cowboy wisdom at the center of a composition, not on the grand, sweeping vistas that surround them. At the heart of his work is a process of subtraction, of winnowing away everything that distracts the eye. And that’s not so easy to do. “I once knew an artist who was commissioned to do a piece, and it was taking longer to get done than the customer thought it should,” he recalls. “The artist told the lady that it wouldn’t take so long if he didn’t have to leave so much out.”