Not even Jude the Obscure, well-known Brownsville palmist, could have forecast such a startling turn of events during the five days Texans attended the 37th Democratic National Convention in New York City.

If the truth be known, most of the 130 delegates and the hundreds of Texas politicians, reporters, and hangers-on were not keen on legging it to the East in the first place. It was not the politics. For once, the Democrats had paid attention, gotten the drift, and things were in order. It was the threat of The City, a place known to be full of human scorpions, arch symbol of Yankee putdowns and eastern decay, polar opposite of wide-open spaces.

Why, then, five days later—after the Reverend Martin Luther King, Sr.’s primordial benediction—was New York City Mayor Abe Beame, standing five-foot-two on the bandstand of the Rainbow Room atop Rockefeller Center, looking like Yosemite Sam in a twenty-gallon Stetson, thrusting a hook-’em-horns sign toward the roof, telling of his love for the hundred or so gathered Texans, and inviting everyone to his office tomorrow at 9 a.m. for a city hall tour? Not with Californians, Michiganders, Ohioans, or even—pragmatically—Georgians, you understand, but with Texans. The whole convention was a love-in, as everybody has by now heard ad nauseam. But the biggest love-in of all turned out to be New York for Texas and vice versa. Who would have thought it, after all, thought that those old antagonists, the melting pot and the frontier, would have finally got together and picked each other out to love and honor, out of all the states in the USA?

Why were these hordes of Texans in the Rainbow Room grabbing startled New Yorkers who were working quietly on their chicken Kievs, and hustling them around the dance floor, yipping to a rather restrained “Cotton-eyed Joe” as interpreted by trombonist Warren Covington? Oscar Mauzy, Bob Armstrong, John Bigham, Shannon Armstrong, David Wolfe, Bob Strauss, Neal Spelce, Pedro Medrano, Ron Waters, Bill Kugle, all dancing with strangers, and all at the express invitation of Hizzoner himself? What did prompt Daniel Patrick Moynihan, candidate for the U.S. Senate in New York, to embrace Calvin Guest, the state’s Democratic party chairman, like he was the prime minister of Israel? Here’s what—

SUNDAY. It started badly, for what ended with a hugging started with a mugging, that quintessential New York crime. Hall Timanus, the lone Texas George Wallace delegate and the Alabama governor’s loyal minion in Texas for eight years, had his worst Edgar Allan Poe nightmare come true late Saturday night. Walking toward the Hotel Pierre for a nightcap, Timanus was grabbed from behind by a six-foot-two black man and robbed of $500. A richer sort of irony would be hard to invent, and the mugging remained the best guffaw of the week. “I’m going up to ole Hall and ask him if this is going to make him a racist,” grinned alternate delegate Neil Caldwell, the delegation’s resident wit.

Timanus suffered further indignity when he had to ask a fellow law partner Monday night to spring for his supper at the Arboretum, for he had not a bean. Finally, George and Cornelia Wallace personally invited Hall to a party at the home of his wife’s publisher (Lippincott) to celebrate her upcoming book, C’nelia. Out of that came a good chat for Timanus with Walter Cronkite and with Steve Bell, one of the newscasters on ABC’s A.M. America. Bell and America host David Hartman interviewed Timanus later in the week.

The arriving delegates found mid-Manhattan clean and festive. Coca-Cola furnished the 50 state flags lining Fifth Avenue, known during the convention as “Avenue of the States.” Revolution-era flags hung up and down Park Avenue. The Empire State Building, from the 72nd floor up to the 101st, was lit up red, white, and blue (henceforth R, W, and B). The 60 men put on overtime by the Sanitation Department, at $115 per man per shift, were for once doing the job. The lights on the Rockefeller Center and Columbus Monument fountains were switched from white to R, W, and B. Even the hookers looked nice, wearing long gowns to imitate the squares visiting from the outback. The city’s new anti-loitering law, which went into effect at 12:01 a.m. Sunday, had cleared out most of the street ladies, although delegates so inclined had no trouble finding them.

The ringmaster of the whole shebang was a Texan, of course, and on this sweltering Sunday afternoon Robert Strauss was being honored at a midday brunch at 21, known in New York as The Numbers. Strauss was clearly the man of the hour, and he was loving it, even if on the eve of the convention the tension was almost unbearable. With Democrats, who knows what could happen? In his four years as the Democratic party national chairman, Strauss had unified the party, which after the Chicago convention in 1968 and the McGovern campaign had seemed destined for the political scrap heap. Even the staggering debt had been reduced from nearly $10 million to $2 million. Carter himself arrived with his wife Rosalynn, and Strauss, true to fashion, stopped lunch and helped work out a compromise over a demand by feminists for a 50 per cent women’s quota next convention. Strauss charmed a solution in the best spirit of the Jarrell, Texas, Fire Department, which wrote on this year’s annual BBQ poster, “We go to your fire. You can come to our supper.” It was Jimmy Carter’s nomination, but on Sunday it was still Bob Strauss’ party.

A few blocks away in the Essex House, Texas delegates were preparing to attend the Rubber Tree Picnic, a bash at Pier 88 on the waterfront that Carter was throwing Sunday night for all 5000 delegates. The pier was forested with hundreds of skyscraper office plants. Ten thousand pieces of Kentucky Fried Chicken, 900 gallons of cold beer, one ton of cole slaw, and 250 pounds of fresh raw peanuts flown in from you-know-where were gulped down as the Carters stoically shook hands. Warren Covington’s Band showed up, as did Telly Savalas, Jerry Brown’s sister, Jimmy Carter’s brother, jazz pianist Hank Jones, and the Philadelphia Mummers, a band of grown men wearing R, W, and B headdresses. Later, most delegates felt the convention officially started with the Mummer’s appearance on Pier 88.

MONDAY. At the first Texas caucus, Carrin Patman, a former Texas Democratic national committeewoman and wife of State Senator Bill Patman, son of the late Wright Patman, spoke about outlawing winner-take-all primaries. They were so outlawed by the convention on Thursday. The thing one notices about Ms. Patman is that she wears very red lipstick and a Texas version of Italian director Lina Wertmüller’s famous white-framed glasses. Cat-eye, I believe, is the shape. Betty Gatlin, psychology professor at Saint Philip’s College in San Antonio, was unanimously elected to replace the deceased G. J. Sutton in the delegation. Democratic national committeeman Jess Hay, one of two men heading up Carter’s national fund-raising effort, finally got a seat in the delegation, replacing absent Dallas City Councilwoman Juanita Craft.

The Texas caucus meeting quickly deteriorated into pitiful whining about guest tickets—the coded, numbered, colored, cardboard cards that meant everything. The 34,000 sets of credentials issued each morning (twenty categories, twenty colors) were supervised by credentials boss, Dallasite George Dillman, ex-chairman of the Bonanza Steakhouse chain and veteran of the last four national conventions. Dillman might just as well have been Tibetan for all the good it did the wrangling Texans. The stalking of prized colors began and did not cease until Thursday night.

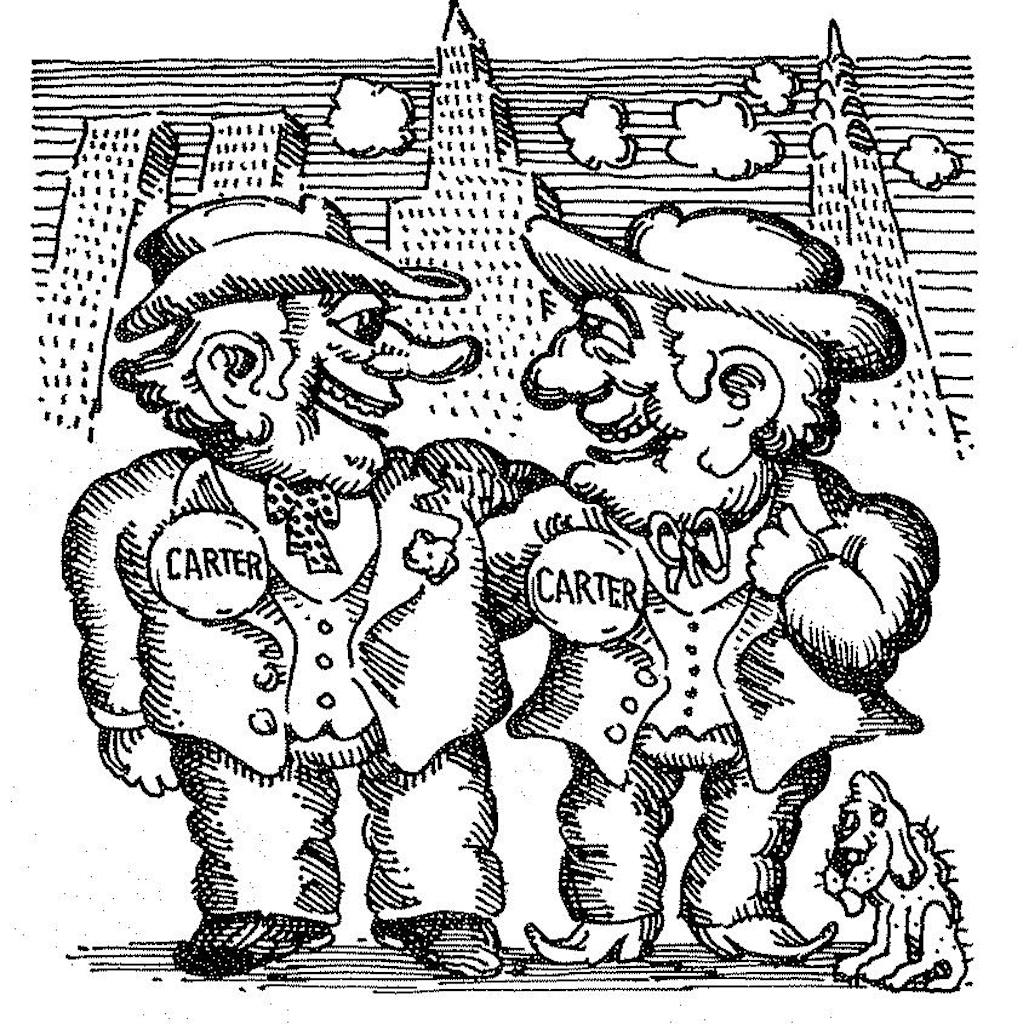

San Antonio’s Nancy Fuller started selling her homemade Carter grinning-teeth buttons, 4000 of them, for two bucks each. Thirty-six Carter straw hats sold in the Essex House lobby in a New York minute. Rick Gentry, a Carter delegate from Austin, was also in the button business. Not only did he have some classy Carter buttons, he also had made up some Barbara Jordan for vice president buttons, which turned out to be like having a Coors franchise.

Meanwhile, at Madison Square Garden, Dallasite Clifton Cassidy headed up security arrangements in and around the twelve-story (nine above, three underground) coliseum. (Texans did everything at this convention except drive cabs.) Cassidy, a member for six years of the Texas Public Safety Commission and, like Dillman, a veteran of four national conventions, worked with Miami Chief of Police Rocky Pomerance, 29,000 New York police, 400 unarmed convention security workers, and an unknown number of Secret Service to make sure none of the 250,000 commuters using the Penn or Long Island railroad stations below the Garden, or the 18,000 folks entering and leaving the convention each day, caused trouble. No one did. Was it because, as Art Buchwald wrote, the subways on early Monday morning carried New Yorkers only one way, out of town, abandoning Manhattan to the battalion of rubes and geeks from west of the Hudson? Or was it because the youth—the L. L. Bean junkies and veteran yippies from 1968 and ’72—were not only burned out, but were also the respectably dressed delegates inside? Who knows, but here are a few dangers New York’s finest coped with around the Garden and Statler Hilton Hotel: Jane Fonda and husband Tom Hayden arguing in front of the Statler; a tanned, bearded man dressed like an angel with flowing robe, aluminum wings, and carrying a harp (“I am Ramazan, the angelic janitor,” said the angel); a spacy black man dressed like Moses, complete with beard and staff, wandering through the lobby; a man wearing a papier-mâché mask of Gerald Ford, selling Nixon pardons for $2; near the corner of “Toidy Toid ’n Seventh,” another man whose face was covered with a mask showing nothing but grotesque red lips and flashing white teeth; and a mime-like Uncle Sam who danced with whomever hopped the barricade.

On Monday night Texas Congresswoman Barbara Jordan’s speech blew away John Glenn’s hopes for higher office. Gentry’s Jordan buttons shot up from $3 to $5, and he quickly sold out. Earlier in the day, Bexar County Commissioner Albert Bustamente lost twelve bucks at Belmont. Uncommitted delegate Lanny Sinkin from San Antonio began working on getting convention rules changed so draft resister Fritz Eufaw could speak on the question of amnesty. Sinkin, rumpled from his three-day Amtrak ride, also began vigorously promoting his own presidential candidate, Morris Fishbein. “Ask not what you can do for your country, but what’s in it for me,” was Fishbein’s slogan.

At the Essex House around a back table gathered Eric Sevareid, Bill Moyers, and Dallas Times Herald publisher Tom Johnson. Our two Texans had brought the sage of CBS over to see the sort of people who were taking over the country, not to mention who might, if Moyers’ CBS convention coverage was any indication, be making Sevareid obsolete. Johnson, who is in Dallas via Georgia and the LBJ White House, was marveling over the dedication of the Georgia faithful who had been with Jimmy from the snows of New Hampshire and even before, who had left home and family to follow him to the promised land, on not much more than a promise. If it had not been clear from the beginning, on Monday night it was clearer than Times Square that the Barbara Jordans, Bob Strausses, Bill Moyers, and Jimmy Carters were going to be running this convention and most likely the country. With such confidence, the long-festering inferiority complex we provincials have had about New York began to melt. Why, they were just like us, real nice and natural, and darned if that Eyetalian food wasn’t as good as old Tex-Mex! The germ of Thursday night’s Texas-New York party was already beginning to grow.

For the night-owl social climbers, there was Rolling Stone magazine’s gathering for Carter staffers at Automation House on 68th Street hosted by the Stone’s Washington office manager, Anne Wexler, and luxuriated in by the magazine’s publisher, Abilene’s Joe Armstrong. Wexler also was Carter’s chief honcho at the Rules Committee sessions in June and is married to Joe Duffy, Carter’s issues’ coordinator (who was unable to penetrate the crush to get in; there is some justice). Because the original guest list of 450 was tripled, thanks to stargazers and hundreds of phony invitations printed by prankster Dick Tuck (saying “Come one-Come all”) the real party was in the street among the proletariat who couldn’t, or wouldn’t, get in. Texas author Larry King was singing, “Ruby, Don’t Take Yore Love to Town,” on the hood of a limo with old girl friend Barbara Howar and John Siegenthaler, publisher of the Nashville Tennessean. Only Walter Cronkite had no trouble getting through the crowd, which parted for him like the Red Sea. By four it was all over.

TUESDAY. Mrs. Valerie Kushner, a Carter supporter from San Antonio, started the day having a private breakfast with her candidate of 4972, Senator George McGovern. Mrs. Kushner, an alternate McGovern delegate from Virginia four years ago, was a traveling volunteer speaker in the senator’s ill-fated campaign and had made a seconding speech well after midnight that nobody heard. But Bob Strauss would brook no amateurish handling of TV at this convention; the speeches would be during prime time and they would be on schedule.

Billie Carr, the Houston liberal Democratic leader and one of three chairpersons of the national progressive New Democratic Coalition, had her office on the Statler’s third floor in full swing. Carr and her eight co-workers—including Geneva Fronek, Mary Lee Whitley, Norma Jo Schweiger, Billie Allen, and son Billy Carr—worked on feminist issues and on getting black California Congressman Ron Dellums’ name in nomination for vice president before the convention Thursday night. (After some hush-hush negotiations with key Carter people via the ubiquitous Strauss, Barbara Jordan took herself out of the VP race.)

Tuesday night’s convention work was as dull as watching a pat of butter melt, as was just about everything between Barbara Jordan and Daddy King. Delegates decided whether to go see Paul Newman and Birch Bayh at the caucus of Energy Action Committee at the Statler’s Georgian Room or Teddy Kennedy at a much more exclusive party given by philanthropist Mary Lasker for Texas Congressman Bob Eckhardt’s Democratic Study Group. Lasker’s party was where rich people wear rich things, in support of the congressmen most inclined to soak the rich.

Those who hadn’t earlier OD’ed on Chinese food at Pearl’s, French cuisine at Lutece, or Italian wonders at Angelo’s hoofed it up to the Bella Abzug Ice Cream Party fund raiser at 11 p.m. on the Saint Moritz Hotel’s 31st floor, a block or so down from the Essex. There was Bella in rouge, a dress with peach-colored flowers, and a peach-colored floppy hat, peanut ice cream dripping down one arm, singing with Shirley MacLaine (black dress, tortoiseshell earrings) who had dropped over after her show at the Palace. Barbara Howar didn’t care that Lily Tomlin didn’t show or that the “Bella” buttons ran out, and neither did Bill and Paula Kugle. Bill’s an alternate delegate from Athens—the one near Tyler. The party was hot and cramped, but the terrace view was grand.

WEDNESDAY. This was Jimmy Carter’s big night. Carter asked Governor Dolph Briscoe to represent him at the drawing, earlier in the day, to determine the sequence of presidential nominations. Briscoe drew number one out of a wooden box, his most successful effort of the convention. Rabbi Gerald J. Klein of Temple Emanuel in Dallas opened the night session with his invocation and at 10:15 Ohio put Carter over the top. At 10:27, Texas cast 124 votes for Carter, 4 for California Governor Jerry Brown, and 1 each for George Wallace and Leon Jaworski. Unlike 1972, Governor Briscoe did not get confused and vote for all contenders. Carter was declared the party’s nominee eighteen minutes later.

Two Texans interested in higher office decided it was high time the state’s delegation partied together, so Houston Mayor Fred Hofheinz (Senate, ’78) and Attorney General John Hill (governor, ’78) threw one on the Essex House’s third floor. There were no cups, no air conditioning, no ice, and quickly, no whiskey. Soon there were no guests. Another prominent politician with no official business at the convention, New Braunfels Congressman Bob Krueger (Senate, ’78) worked the Texas crowd just as hard as anyone.

Speaking of campaigning, ex-State Senator Don Kennard was doing some impressive spadework for Congressman Jim Wright of Fort Worth, who was using the convention for some typically gentle but effective lobbying in his bid to become House majority leader. Wright had given Kennard the task of making contact with the newly nominated congressional candidates who were attending the convention, just so they would remember that it was Jim who could help them so much in their campaigns, since he was, coincidentally, chairman of the Congressional Campaign Committee. Wright, insiders say, has a good chance to win.

A more obscure campaigner was Fred Fox of Houston, an ex-Marine who was at the convention lobbying for the U.S. Trust Territories of the Pacific Islands, or Micronesia. The genial Fox was passing out “I Like MIC” and “I remember” buttons while making his case for full territorial status for the tiny islands, the last trust territories in the world.

Texas House of Representative members Luther Jones and Mickey Leland and Lufkin Congressman Charles Wilson joined Texas House member Buddy Temple (and, briefly, Temple Industries and Time, Inc. power Arthur Temple, Sr.) for lunch at 21, where they swapped political gossip under a Chicago Daily News truck hanging from the ceiling of the handsome wood-paneled landmark. Scattered around the first floor were Ethel Kennedy and writer Alexander Cockburn; Barry Goldwater with Ben Bradlee and Sally Quinn; Lawrence Spivak, John Chancellor, Jack Anderson, Richard Daley, Katherine Graham, Iranian Ambassador Ardeshir Zahedi (perhaps the most powerful man in the room), Austin American-Statesman reporter Jon Ford, and former Dallas City Councilman Garry Weber, up to help out his good friend in security, Clif Cassidy.

The week’s hubba-hubba political figure, Jerry Brown, and United Farm Worker leader Cesar Chavez hosted a fund-raising event Wednesday at 5 p.m. in the Hotel McAlpin, a cheapo place near Herald Square where the ascetic 38-year-old Brown reportedly slept on a mattress on the fifteenth floor. Dallasite Lee Clark was there to get the story for Channel 13, as were Brown supporters from Texas—Dolores Tarlton (Sissy Farenthold’s sister-in-law), Gertrude Barnstone, Paul Moreno, and Orelia Garza. So were Jane and Tom; Hayden’s victorious opponent, California Senator John Tunney; the other California senator, Alan Cranston; and lots of people drawn by the young governor’s sexy eyebrows. The guacamole was bland; ceviche, not bad; tostados, not unlike hardened plaster of paris; sangria, appreciated and in short supply; frijoles refritos, brown wallpaper paste. Chávez barely spoke. Brown spoke a lot.

THURSDAY. Carter announced at 10 a.m. that Senator Walter Mondale was his vice-presidential choice, disappointing Governor Briscoe, Calvin Guest, Lloyd Bentsen, and Amy Carter, all of whom were pulling for John Glenn. Senator Bentsen, by the way, a forgotten man by everyone except Republican challenger Alan Steelman, showed up Monday night to shake hands with the Texas delegates and disappeared, taking whatever remained of his own presidential dreams into the sunset. Hoping Mondale would get the nod were longtime Texas Carter supporters Dan Weiser, Pat Pangburn, George Goodwin, and John Pouland, Carter’s 22-year-old statewide organizer. Pouland was the convention’s big loser. He had lived out of his car on $75 a week for months last year organizing Texas for Carter, gathering 25,000 signatures to place the unknown governor on the May presidential ballot in all 31 senatorial districts. When the big boys got on the bandwagon months later, Pouland was denied a place in the Carter delegation. He squeaked in as an alternate. The somewhat disillusioned Pouland will enter law school this fall.

The delegation cast 126 votes for the Minnesota senator, 1 vote for Barbara Jordan, and 2 for Fritz Eufaw. It was one of Eufaw’s supporters, Glen Maxey, working with Carter delegates Clarence West, Charles Yates, and Hayden Woodward, who devised the “Texas Thanks New York City” flash cards that brought tears to the mayor’s eyes and prompted the Pied Piper charge of Texas delegates down Sixth Avenue to begin the Rainbow Room siege one hour later. Even Governor Briscoe chipped in, gracefully making New York an “Honorary Texas City.” Later, Land Commissioner Bob Armstrong, Carter’s key Texas man, went to a party for Carter staffers. The young Georgians were exultant. So was Armstrong; he was also exhausted. After the weekend, he was admitted to an Austin hospital with pneumonia.

So there you have it, a near-perfect convention for a variety of reasons, all grouped under the larger banner “Fate and Luck.” Unlike 1924, when the Democrats last met in New York and a twenty-minute thunderstorm with 72-mph winds stranded 53 buses carrying delegates to Yonkers, the weather was perfect. For the record, only 70 bomb threats and four threats against political leaders were logged; all proved harmless.

The Democratic Party was healed, at least temporarily. Outside the Garden an entire city, having gone through a great financial crisis, had realized, finally, that it was a part of all those provinces out there, stretching forever west of the Hudson. As the number one province, we were probably the natural choice to feel the warm glow of this long locked-up sort of, well, love. It may have been Jimmy Carter, it may have been the Bicentennial, it may have been the end of the Viet Nam War, it may even have been only Bob Strauss’ careful planning and the smell of victory in November; but whatever it was, it didn’t seem phony. So if you are in New York, don’t be bashful about asking the band at the Rainbow Room to play “The Eyes of Texas.” They know it now, and even seem to like it.

- More About:

- Politics & Policy

- Larry L. King

- Barbara Jordan