This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

On the afternoon of All Souls’ Day, 1979, Walter Martínez and his wife, Martha, left their office on Buena Vista Street in San Antonio’s West Side barrio and set off through the gusty weather for Grandfather Cecilio’s house, taking an indirect route to see the flower stands. The rain and cold of late autumn always left the barrio bare, austere, revealed. The banked rows of flowers that had emerged almost overnight on the street corners and blanketed the San Fernando Cemetery provided welcome splashes of color. Elsewhere the barrio appeared seamed and sere.

The previous night, congregations from many barrio churches, including Our Lady of Guadalupe, where Martha and Walter had been married in July, had marched through the streets to the cemeteries, carrying candles and singing hymns to honor the memory of those who had gone before. Walter and Martha did not march in the processions, nor did they regularly attend mass. Like other young Mexican American couples, they have ambivalent feelings about religion, are pulled between secular America and the enveloping Church of their ancestors. The collision of cultural values has affected many areas of Walter and Martha’s life. They have had to determine what in their Mexican heritage should be put aside and what is of value for the way they live today.

Often the choices are basic. Are they Mexican Americans, Mexicans, Hispanics, Americans of Mexican descent, Chicanos, Spanish Americans, Latin Americans, or Spanish-speaking Americans? What language do they speak and to whom? In a single afternoon on the West Side one can use English; proper Spanish, with its stilted forms, to the elderly; middle-generation Spanish, laced with anglicisms, to businessmen; and the pachuco patois of the street, with its secret slang words and double meanings. The great-grandson of a man who grew up a Mexican peasant, Walter is college educated, a seasoned political worker, an American; yet even his name—part English, part Spanish—is a constant reminder that he is a person of two cultures.

In many ways Martha and Walter are like everyone else in America: descendants of immigrants. But they are also in some ways unique. Their forefathers did not make an abrupt transition, did not strain or sever ties with the home country by crossing an ocean as had the European and Asian minorities. They crossed the Rio Grande to a semiarid, largely treeless desert country with basins, mountain ranges, and coastal plains like those of northern Mexico. They settled with millions of their compatriots in an isolated border region 150 miles wide that stretched from Los Angeles to the Texas Gulf Coast. There they kept their traditions, their religion, their language, and their ties to Mexico.

At the same time, the two cultures did mingle to produce much of the cultural richness of Texas. The Anglo influence on Mexicans in Texas has been great; the imprint of the Latin marks the state’s political institutions, language, economy, architecture, and customs. The Mexicans brought the Longhorn and the first brand—the three Christian crosses of Cortez. Everything the Texas cowboy used, except his six-gun, came from the Mexican vaquero: terminology, clothing, utensils, equipment. The first Texas homestead law, enacted in 1839, was patterned after the Mexican version. Irrigation practices, geographical names, adobe architecture, and the first goats, pigs, horses, hoes, wheels, peaches, olives, plows, and cottonseed all came from Spanish and Mexican settlers.

Uniting the Latin and Anglo cultures in those days would have been as difficult as combining their neighborhoods today, and for the same reasons. One was the language barrier. In addition, Mexicans knew little of Anglo law or self-government, Catholics and Protestants barely tolerated each other in the nineteenth century, and even though many Mexicans had worked under a peonage system, most were violently opposed to slavery. These differences produced cultural shocks, not unlike those in the Middle East. For many Mexicans the Texas War of Independence and the U.S.-Mexican War of 1846 remained for decades bitter and humiliating memories. There was a vaguely expressed feeling among Mexicans that the Anglos had taken their land. That grand tourist shrine and symbol of liberty, the Alamo, was not popular in San Antonio’s huge barrio, El West Side.

El West Side is the urban equivalent of the colonia in the Southwest’s small towns—the other side of the tracks, where Mexican communities grew up because of nearby industries or cheap land or lower rents. Although the urban center of San Antonio was settled by Spanish soldiers and priests, it has been the Anglo power base since the coming of the German immigrants in the 1840s. El West Side is the geographical and spiritual home of the Mexican in San Antonio, as are Loma in East Austin, Quinto in Houston, Segundo in El Paso, and El West Side in Denver.

The history of Texas is the history of Anglo and Mexican together, inseparable, but mixing usually only a little, like oil and water. Today one in four Texans is of Mexican descent, and their numbers are increasing every year. To understand the life of Walter Martínez, American, is to understand much of the cultural history and future direction of Texas. And to understand Walter, we must begin south of the Rio Grande, in Mexico.

The Uprooted

On a beautiful day Pedro Martínez and his family left the state of Jalisco for a new home, far to the north, in the United States. They left in a hurry, as did so many others. Four years of revolution had made living in Mexico impossible. The Martínez family had felt the shock waves of the revolution more than the other villagers at Hacienda de Languillo. One day in 1905 Pedro had been overseeing the field-workers as always. The next he was gone, conscripted into the Mexican army, not to return home for five years. Those were terrible times for the Martínez family, but the owner of the hacienda, their patrón, was understanding and friends brought food and clothing and helped keep them together. Often the family would go to a nearby village to visit the shrine of Nuestra Señora de San Juan de los Lagos, the patroness of journeys, of comings and goings in life, and there they would pray for Pedro’s safe return. Even though he was a small boy, Cecilio, the only living son, knew he was the man of the house while his father was away; he worked hard helping his mother and, especially, looking out for his four older sisters. His father’s sudden absence affected Cecilio the most. He loved his father; now he felt like an orphan in a village where homeless children were as rare as families with no children at all. He never forgot that feeling of abandonment. Even after Pedro returned, Rómula, his wife, refused to believe that he would not be conscripted again, perhaps next time by the Villistas. She knew the family could not survive another prolonged period without Pedro.

One night at the table after supper, Pedro, his tired face bathed in candlelight, told his family that he had a sister living in San Antonio where many other Mexicans lived. According to her letters, it was a strange country without saints or shrines, a country where the winters were cold, but men did not disappear overnight into armies and life was easier than on the hacienda. Pedro’s sister, Nasaria, had two rooms on Guadalupe Street near the railroad tracks, and Pedro knew she would welcome the family, because she had been blind since birth. The family thought it a good omen to start their life in America on a street named after the Virgin Mother, the symbol of the poor and humble, the greatest of New World saints. It would be crowded and the servings of food would be smaller, but with God’s blessing they would survive.

So in 1914 Pedro and Rómula and four of their children joined the thousands of their countrymen hurrying north to begin a new life in a city they had only heard of: San Antonio, Texas. They were leaving not only a home but a way of life that had existed for centuries—a small, isolated, nonliterate, and homogeneous folk society where life was seen as a fulfillment of God-given roles rather than as a struggle for riches and power. There was a strong sense of place, of identity, of belonging. Working the land was a natural and noble task, formal schooling did not exist, native folk rites were interwoven with church rituals, and women never worked outside the home except in the fields.

The New World

If the European immigrants’ first view of the U.S. was New York City from Ellis Island, for Mexicans like the Martínez family it was the vast scrub-brush country that surrounds Laredo and El Paso. The Mexicans’ points of entry were not teeming cities but wherever there were jobs. The first Americans many Mexicans saw were labor contractors signing up workers for railroad, mining, and agricultural companies. But many of the immigrants, like the Martínezes, continued north, through the South Texas brush country that looked exactly like the land they had left, past dusty towns carved out of cactus and mesquite, a vast expanse where nothing stirred and the heat lifted only long after dark.

On his first day in San Antonio Pedro noticed not the buildings or the masses of people or the motorcars but that the town smelled of tripe, a familiar odor to a ranch foreman. The train had stopped not far from their destination on Guadalupe Street, near the stockyards and slaughterhouses where many barrio residents worked. The family climbed down and stood on American soil for the first time, weary, bewildered, excited, overwhelmed by the noise and crowds. Vendors rolled their pushcarts by, shrieking like gulls about their wares. Labor contractors, hiring-agency men, insurance agents, small-loan hawkers, and peddlers—all speaking Spanish—competed for attention. Pedro had been warned to avoid these people; they offered dazzling merchandise on the spot, abruptly introducing the new arrival to the American system of buy now, pay later. They seemed to have the patience of a hunting cat, and they probably could have sold grasshoppers in a locust plague. Pedro and Rómula learned soon enough that in this country the barter system, the way they had paid for things all their lives, was the practice only among neighbors.

Pedro’s sister lived in one of the barrio’s corrales, a row of ten two-room apartments all opening onto a back yard, or corral. There was no electricity—everyone used candles or kerosene lamps—and no plumbing. Several spigots for drinking water were in the corral, as was the one bathroom, where residents lined up early in the morning to do what only the dead found unnecessary. The Martínezes had a wood-burning stove, but many families cooked outside over open fires.

Like many corrales near the tracks, on the eastern edge of the barrio, their building had been constructed by a railroad company—it was painted “Santa Fe yellow”—and sold on a contract-of-sale agreement, which meant that if the rent wasn’t paid, the home was lost. They had no equity, and often the company would refinance an $8000 home several times until the owner ended up paying three times the original price. Pedro Martínez vowed this would not happen to him—he would build his own home, and several for the rest of the family if he was lucky.

But first he had to work. He did not understand his new country, but he did understand hard work. Pedro worked everywhere: construction projects, yard work in affluent neighborhoods, odd jobs downtown. Cecilio found a job washing dishes at the Savoy Café for $10 a week. His sisters Petra and Guillerma worked first at a cigar factory, then as pecan shellers. Guadalupe, the most religious daughter, managed the household with Rómula. She never missed a mass at Our Lady of Guadalupe Church. When troubled, she would kiss the rosary and repeat prayers endlessly, sometimes until tears soaked her black lace mantilla.

The Great Migration

When the Martínez family boarded the train for Texas, they followed a tradition as old as Mexico itself. The country’s history had begun with migration: the Aztecs themselves originated as a tribe of wanderers who traveled south to establish a great nation on an island where they saw an eagle devouring a serpent—now the site of Mexico City. Subsequent upheavals—revolutions, wars with Texas, the U.S., and France—had caused an ebb and flow of Mexican migration. There were religious migrations, pilgrimages to the shrines of popular saints to give thanks for a prayer answered, a sickness overcome, the return of a loved one. The migration the Martínez family helped begin continues to this day, a movement of people comparable to the Anglo settlement of America.

At the turn of the century the flow north from Mexico that had long been a trickle (a yearly average of 335 Mexicans entered the U.S. from 1861 to 1900) became a torrent. From 1900 to 1930 more than one million Mexicans, 10 per cent of the country’s population, left for the United States. The economic boom of the Southwest had begun; the dirty, ill-paid, irregular work, always the province of the newest immigrants, fell more and more to the Mexicans. Many of them followed the seasons and harvests from citrus groves in the Texas Rio Grande Valley to sugar-beet fields in Minnesota to apple orchards in Washington. Some migrated with the railroads—Mexicans made up 70 per cent of the rail gangs laying track across Texas, New Mexico, and Arizona. Others followed in Coronado’s footsteps, mining gold and silver, moving on when the ore played out. To tell the story of Mexican immigration to the United States is to trace the rise of the great regional industries—railroading, mining, fruit and vegetable growing. Mexicans built, planted, mined, and harvested, bringing forth riches from the arid soil. But rarely for themselves. When times were good, the Mexicans were welcomed. When times were bad, they were always the losers in battles with Anglos for jobs, power, land, and recognition.

During the Depression the U.S. government deported more than 300,000 Mexican immigrants. In the forties, when labor was scarce, the government began the Bracero program, importing Mexicans for agricultural jobs only to send them home when the work was completed. Between 1953 and 1956 Operation Wetback sent two million legal and illegal immigrants back to Mexico. Today a million legal and illegal Mexicans per year still migrate to this country across the two-thousand-mile border, still working at the dirty jobs, and prompting such defense measures as a $3.5 million, eighteen-mile-long, ten-foot-high fence that the Immigration and Naturalization Service, two years ago, suggested building along the Mexican border.

Life in the Barrio

The San Antonio barrio where the Martínez family had settled was like an urban Mexican village, with familiar foods and markets, churches, Spanish-language newspapers, music, fiestas, a common language, and an overwhelming number of Mexicans. It was separated from the alien, non-Mexican world by both invisible and physical barriers. It was a spiritual as well as a geographic zone, with its own particular heroes and traditions, code of ethics, and aesthetics. But it also was literally cut off from the rest of San Antonio by creeks, railroad tracks, gullies without bridges, highways, and, later, freeways. These walls isolated and segregated the newly arrived Mexican family, allowing them to retain their cultural traditions but making it very difficult for them to enter the Anglo culture and learn the ways of their new country. The barrio was a refuge where a family felt at ease, close to friends, familiar surroundings, and values. It was a temporary stop on the way to a “better neighborhood.” For some who had no choice but to stay, it was a prison. It was like a small Latin American country, dependent on foreign markets—downtown—and forever subject to a dominant Anglo society that, like the moon, pulled the tides of the barrio this way and that.

Cecilio got to know the barrio, its customs, the street characters, the neighbors, and the people recognized for their special skills: Don Jesús, the musician, who hung a dozen or so whiskey bottles in his garage, filled them to different levels with colored water, and played them like a marimba; the rag collector, Don Pedro Guerrero, who drove his bobtailed truck through the neighborhood, collecting trash and giving Cecilio and his friends rides on the tailgate; Don Chanito, the barrio firewood provider, whose neighborhood route could be charted by the noise of the saw mounted on the back of his truck with which he cut oak into stove-length chunks. Doña Chole made the best tortillas, flattening the dough into a perfect pancake shape with one hand, turning over the ones cooking on the hot plates of the wood-burning stove with the other. Every so often she would pick a tortilla off the stove top, coat it with bacon grease, roll it into a tight cigar shape, and hand it to a child who had wandered in.

There were businessmen on the West Side, men who were highly regarded because they had no boss; Don Jesús Hurtado, the first Mexican American to own a service station on Guadalupe Street, who was later murdered by a junkie for a pack of cigarettes only a month before his retirement and first vacation; El Maestro Barbero, who always asked each customer, “Natural, thin, or light around the ears?” El Maestro had penny gum for the kids, offered special discounts for large hairy families, and was famous for giving babies their first haircuts without damaging the baby locks prized by mothers. And everyone knew Don Pancho, a self-made man who had taken two old trucks and built up a small moving business that was successful despite its mixed-up name, Vásquez Transfer and Sons Company.

Cecilio often saw the three deaf-mutes around. One was known for his loud whistling; another could say two bad words in a loud, distinct voice; and the oldest boy was known for swimming like a fish in the dead of winter in the pond near the Belgian Garden truck farms. The whistler became a janitor at Our Lady of the Lake University; the profane one walked around the barrio immaculately dressed for the rest of his days; and the swimmer aimlessly rode his old bicycle through the neighborhoods, stopping for a swim on the coldest days of the year, entering the water like a knife and effortlessly gliding to the other side. People in the barrio tolerated the eccentrics, the fools, the troubled. Individuality had long been a basic tenet of Mexican values.

Drunks were a great part of barrio life too. Cecilio watched shoe-shine boys polish the same drunk’s shoes twice in a day; saw the hapless topers wrestle telephone poles and fight each other without landing a blow; watched the younger boys earn a dime by guiding them home; watched them do strange things like swallow carpet tacks on a bet. Pedro Martínez warned his son that the barrio produced all kinds of men, sometimes hard characters who “ate iron rails and deposited iron nails,” whose arms wore bracelets of scars and wounds from years of hatred and anger. They wielded their knives with an intensity matched only by their curiously poetic insults: “You are afraid, cabrón. Your nostrils flare like those of a frightened colt. You insulted me with breath of sulfur, with vampire teeth. Your eyes are bloody and they lie. I will make sure you foam red at the mouth.”

“If you don’t wish to discover fleas, don’t comb the dog,” said Cecilio’s father when his son asked him about such men. Pedro was fond of dichos, sayings that had been handed down for generations in the oral tradition of his culture: proverbs and aphorisms that helped teach a child about life. When Cecilio or his sisters would compare unequal things or mix up their reasoning, Pedro, sitting as always at the head of the table, would tell them, “You cannot plant a squash seed and get a melon.” When his children would try to bend the rules to get their way, they would hear from their father, “The book reads the same even when read upside down.” Whatever the circumstances, the rules did not change, nor did the consequences if the rules were broken.

As in most first-generation Mexican American families, Pedro Martínez was policeman, jury, and judge in his house. His word was law, whether the issue was making a grocery list or planning a funeral. American families usually encouraged a sense of equality, a striving for individual recognition. In the Martínez family there was a hierarchical ordering of members founded on the unquestioned and absolute supremacy of the father. Firm but just, neither capricious nor tyrannical, he ruled by silence and respect, not fear. Cecilio learned his role so early that he cannot remember how it was taught or not knowing it. He obeyed because he never thought to do otherwise.

If his father exercised power through respect, Cecilio’s mother and the other women in the family had power because they were loved. In the Martínez family the most honored members were the oldest and the youngest, especially the babies. Not yet touched by human error and sin, little children, los reyes de la casa (kings of the home), were extravagantly cared for and loved. With the Mexican emphasis on continuity of marriage and on children, and with the purity of daughters and mothers strongly protected, the women, entrenched in the home with the children, had great, if subtle, power. When Cecilio wanted a quarter for the movies, he went to his father, who would usually say with a wry smile, “Ah, hijo, they only get close to the cactus when it has fruit,” before handing the money over. But to discuss his personal life and ask intimate questions he went to his mother.

The Courtship of Cecilio

In 1918 Cecilio quit his job at the Savoy Cafe and went to work unloading gravel and sand from hopper cars at a temporary Army post on the other side of town. He was nineteen. After the first two days his hands were blistered and bloody. “You can’t quit or they will fire you,” an old man on the work crew told him. “Urinate on your hands and they will heal.” Cecilio knew of folk remedies. His family used cobwebs and mud packs to stop bleeding, wet ashes for cuts and rashes, hot asphalt tar applied with a match on warts, and soup made from tender white pigeons to restore strength after an illness. Everyone used yerbabuena, mint leaves that often grew around hydrants, for tea; mixed with salt for toothpaste; or added to Vaseline and coal oil as a liniment. But this was a new one. He discovered that the old man was right. Because he didn’t miss a day, Cecilio soon got an easier job, cutting wooden stakes for surveyors who were adding on to a military post called Fort Sam Houston.

One night after supper, when the room was as quiet as before daybreak, Pedro told his family that he had bought a lot a few blocks south on Wall Street, the same name as the famous street in Nueva York, and a block north of Apache Creek. It cost $125. He had made a down payment and would pay $1 a week until his debt was ended. It was time to build a house. Cecilio brought used lumber from the military post and soon the house was finished, one big room under a slanting roof, with no electricity or plumbing. They would get water from the public well down the street where you filled your barrel for a nickel.

Cecilio best remembers the winter mornings in that first house, waking up in the blue-black cold, catching the smell of coffee and kerosene, seeing his mother in a coat huddled over the stove as she cooked tortillas and sliced papas (potatoes), the others in the family gathering close to the stove’s heat. Finally the morning sunlight lengthened into spears across the linoleum floor, and the rest of the house warmed. After breakfast, no matter what day it was, his sisters went to mass. If it was Saturday, Cecilio would finish his chores and ask permission to go to the Azteca Theater for the Saturday afternoon movies, not so much to watch the singing cowboys and bandits as to see a girl he had noticed in the neighborhood but never spoken to.

Rosa was not only a city girl but she also attended J. T. Brackenridge School and had learned English. Cecilio, quiet and shy and still feeling like a bumpkin, was afraid she would laugh at his overtures. One Saturday in 1921 he went to the Azteca and saw only one seat near the front. He sat down and looked to the right. There, next to him, was Rosa with her friends. She was a beautiful girl with straight, long, Indian-black hair that always smelled fresh from the coconut-oil shampoo barrio girls used; her small, round, expressive face always seemed wreathed in a smile. Somehow he kept his courage from unraveling and said hello. Thus began a five-year courtship.

Courtship and marriage in the barrio of San Antonio had quite different implications than they had back on Cecilio’s hacienda in central Mexico. In the small village, all families prayed the firstborn would be a boy, to work and, eventually, to lead the family. A girl was another matter. Her honor had to be defended; her marriage brought a strange male into the family circle; if she didn’t marry, she was likely to be labeled a cotorra, an old parrot. Young men in the village demanded the “ideal” woman: chaste, delicate, homey, maternal, religious, and beautiful (especially her eyes). A woman who fell short, as most did, had to consider that her husband had done her a great favor in marrying her. While these traits were still prized in the barrio, Mexican courtship and marriage had subtly changed to reflect the Anglo way of life. Cecilio and Rosa went to movies, met after school, and spent Sunday afternoons walking in the neighborhood—all without chaperones—until in 1926 they decided to marry.

Meanwhile, the family had built two more houses, one for Cecilio’s sister and her husband and one as yet unoccupied, for Cecilio and his bride. Cecilio again changed jobs and began working at the Texas Steam Laundry on Crockett Street near the Alamo. For $2 a day, nine hours a day, six days a week, he loaded wet wash into carts and wheeled them over to huge dryers near the “pressing ladies,” who worked in the warm fog produced by their labor, the steam rising from their damp skin. It reminded him of the vapors lifting up from Apache Creek in early winter and of how he had explained to a child once that the early morning dew didn’t mean the grass had been weeping.

After work and on weekends Cecilio often helped his friend Tony Guerrero work on cars at Tony’s filling station. He discovered he had a talent for mechanical work and could often fix what others could not. Once he repaired a big new Buick whose malady had stumped an Anglo mechanic brought from downtown. Rosa enrolled him in a correspondence course on auto repair and read the manuals to him every night. He would take the lesson down to Tony’s garage and carefully study what would become his lifelong trade. He would need it, for soon the Depression arrived, bringing ten years of deprivation and want.

During the Depression, when poverty and hunger twisted and broke the spirit of many of his barrio neighbors, Cecilio’s years of lifting wet laundry and working long hours at night to learn auto mechanics paid off. Not that he had money—no one did—but he had his own business. He opened a service station at the corner of Brazos and Chihuahua (formerly Wall Street) in 1930, the year of his mother’s death. He and Pedro had saved their money to buy the land and had built the small building and carport themselves. Becoming a businessman had been his goal since his days on the hacienda, when he and a friend would take chile peppers to markets where there were none and barter or sell them for a small profit.

If anyone had told him then that he would someday have his own business repairing American automobiles, he would have thought that the moon was more likely to rise in place of the sun. But that was the lesson of America. However, there was a darker side to this American coin: the broken barrio families, the growing number of juvenile delinquents and forgotten old people left like abandoned cars on the street to fall apart, and the deterioration of the social institutions so important to Mexican life on the West Side. Often a bewildered neighbor would say to Cecilio, “I live better here in the barrio, I have more things, but I am not at home in this world.”

The Old Ways Die

After a few years in San Antonio, Cecilio began to see how life was changing in fundamental ways for many of his neighbors. While life in the old village had been hard and mean, it had been stable. There was comfort in knowing that the traditions and culture and fixed habits would not change, that everyone in the family was needed. Living near one’s grandparents, cousins, and other relatives meant security. So did knowing that one’s child had trustworthy padrinos, baptismal godparents who could assume parental duties. A falta de padres, padrinos—in the absence of parents, godparents—meant something in the village. It rarely did in the urban barrio of El West Side.

Now Cecilio noticed families falling apart under the pressures of living with two cultures. How could a man give guidance to his children when he knew less than they did about their new life? In the village the elder’s word was never questioned because the children could see the practical and workable aspects of his wisdom. Now parents often seemed confused, bumbling, disorganized. It was not their fault. Where were the people to tell them about Anglo ways? Where were the programs on Spanish radio explaining laws and public schools and how to become a citizen? Why didn’t the churches help fill out forms along with saving souls? Thrown up against the larger urban world of San Antonio—despite the insulation of the barrio—the village folk culture fell apart. To make matters worse, the change was compressed into a few months or years instead of being drawn out over decades.

The Great Depression wrapped the West Side in the tough grip of circumstance. Men with eyes dead as a gray sky walked the streets looking for work. The pain and terror of hunger turned the faces of beautiful young women into ancient, creased bas-reliefs, wrinkled like old pieces of fruit. Bowed by weariness and trouble, many envied the dead who had eaten dirt and grass at San Fernando Cemetery. It seemed that all 65,000 Mexican Americans living in the four-mile-square West Side barrio were searching for food or jobs.

There were places to find food if you had friends. West of the barrio were the Belgian Gardens, the vegetable farms of the Belgians who had come to San Antonio because of its wealth of land and brown-skinned labor. They could coax two crops a year from the Bexar County soil. No one mixed better with the Mexican Americans than the Belgians. They learned the language, were solidly Catholic, and proved to be humane employers. For years the barrio’s only swimming hole was at Octave Van de Walle’s eight-hundred-acre farm—a muddy pond where the laborers washed the carrots and potatoes. Other Belgians opened bakeries like Camille De Winne’s Daylight Bakery and Ed Welten’s Prospect Hill Bakery, where day-old bread was handed out when the bigger companies like the Fehr Baking Company (later Rainbo) had nothing more to give.

Particularly fortunate were those who worked at the packinghouses—Roegelein, Apache, Auge, and later Swift—and brought home bones to flavor frijoles and soups. The poorest learned to cook with animal blood, to which they added cactus tips and eggs. The blood was ladled out almost every day, but on Wednesdays the companies gave away brains, entrails—tripe for menudo—hearts, and kidneys, which smelled the worst. The Terminal Produce Market, on the western edge of downtown, sometimes gave away bruised produce unfit to be sold. Only a few agencies helped the poor: Associated Charities, the largest private group; the Salvation Army with its breadline; and—the only one on the West Side—Our Lady of Guadalupe Church, which, thanks to Father Carmelo Tranchese, opened a relief depot to distribute clothes and food.

Certainly no help came from the city or county. San Antonio stood almost alone among 94 principal U.S. cities in denying relief to its starving poor. The city refused to pay storage costs for government-surplus food, and so it was shipped elsewhere. The federal government provided over 98 per cent of the welfare funds for San Antonians, both through direct relief and through employment on public works projects. The city was among the poorest in the nation, and the statistics reveal its ugly secret of poverty and neglect. In the mid-thirties, San Antonio had one of the highest tuberculosis and infant death rates in the U.S. Only 9 per cent of the houses on the West Side had inside toilets; only 12 per cent had inside running water. Eight per cent of the population over ten years of age could not read or write. In 1938, the city ranked the lowest among large Southern cities in average weekly earnings per person ($20.18).

During these terrible years the poorest of the working poor were the city’s pecan shellers. Over half the nation’s native pecans were shelled by workers—like Cecilio’s two sisters—who were willing to accept wages of $1 to $2 a week. The workers most hated Julius Seligmann’s Southern Pecan Shelling Company, where wages were the lowest and working conditions the worst. Often as many as a hundred shellers sat at big tables working long hours with their picking knives in rooms thick with the brown pecan dust that was thought to contribute to the high tuberculosis rate among the workers.

When the company’s representatives announced in 1938 that they were rescinding an earlier raise, thus lowering wages back to 5 to 6 cents an hour, the workers, among them Petra and Guillerma Martínez, walked out. There was no other local industry to absorb the largely unskilled workers. So, at the peak of winter, with no savings and no way to pay for food, winter clothes, or medicines for winter illnesses, the pecan shellers were out of work. City officials blamed the strike on communism. The workers were tear-gassed, thrown into cattle trucks, and jailed. Finally Governor James Allred persuaded Julius Seligmann and the union to arbitrate, and the pecan shellers returned to work after the company agreed to pay a compromise wage of 5.5 to 6.5 cents after the first of June.

A Tale of Two Brothers

Throughout the thirties the Martínez family lived side by side in their three houses. Pedro remained in the original house after his wife’s death in 1930. Guillerma, Petra, and Petra’s husband lived on one side, and Cecilio and Rosa and their two children lived in the newest home, just to the west of Pedro’s. The two young boys, Richard and Cecil, had been born a year apart. Another son, Robert, had died at a young age. As in the village, it was comforting to have relatives nearby. They acted as common council in times of decision or crisis. They furnished aid, and if sometimes they limited freedom or interfered, helping hands were always near and no one ever felt alone. Without his relatives, Cecilio would have felt exposed and vulnerable.

Watching the boys grow up, Cecilio and “Mama Rose” saw they were as different as the bark of a tree from the bark of a dog. Richard, the elder one, was quiet, and preferred being by himself. He would go to the Saturday movies late in the afternoon, whereas Cecil would be the first in line to buy his ticket, cutting up with a throng of amigos. Richard spent hours alone, making animal shapes out of wood, drawing, and, most of all, building model airplanes. Airplanes fascinated him from earliest childhood, probably because the family lived in the flight pattern of Kelly Air Force Base, one of four air bases in San Antonio, and aircraft seemed to be as much a part of the sky as the sun.

Richard did well in school, but like other barrio children, he found it baffling at first. “I always loved books, their clean smell, the glossy pages,” Richard said one morning at his home, “but it wasn’t until the fourth grade that the words made sense to me. I could read the questions but not answer them. I had no idea what the words meant. We learned the Lord’s Prayer and recited it every morning like parrots. None of us had any idea what we were saying. Our family, like others, prayed in Spanish, not English. At school we were punished for speaking Spanish. We spoke it in the bathrooms.” After learning English, Richard proved the better student of the two boys. He was also conscientious in other ways. Several days a week Cecilio ordered both of his sons to help him at the garage after school. Richard never missed. Cecil rarely showed up.

Gregarious, undaunted, cocky, street-wise playground and sandlot king, Cecil woke up each morning convinced it would be his best day, with no doubt he could conquer or con whatever the world threw his way. The first time Cecilio took them to the public swimming pool known throughout the barrio as El Caldo, the soup, because of its warm water, he asked his sons if they could swim. “No,” Richard answered, “but I will learn.” “Of course I can,” said Cecil, jumping in over his head without hesitation, coming up sputtering, and dog-paddling to the side. Later in his life Cecil wanted to fly, so he went up a few times with a friend. Then one day he just did it himself—took the Vultee Valiant trainer up, flew around San Antonio, and landed.

Richard was a little resentful toward his irrepressible brother when he had to do all the work at the garage, but Cecilio never got too upset over Cecil’s absence. However, he always tried to be fair. “Richard got the car last time,” Mama Rose would say when Cecil’s request for the car was vetoed by his father. “Who helped me do the work, who took care of it yesterday?” Cecilio would reply, handing the keys to Richard. When Cecil did use the old Studebaker, it would more than likely come back with a dented fender or coast in out of gas. “The boys are different,” Cecilio would tell Mama Rose. “They can’t be the same. Let Cecil be himself. No matter what, he will always survive.”

The disciplinary measures Cecilio had learned from his father he and Rose now used with their sons. There were three stages, and they never varied. First, Mama Rose gave a scolding, sometimes accompanied by a coscorrón, a sharp rap on the head with her knuckles. If the mischief persisted, she issued a warning that Cecilio would be told: “Ahora lo verás. You will see.” Usually that was enough for even the feisty Cecil. If not, finally there would be a reprimand from Cecilio: “¡Ya basta! Enough!” But that was rarely needed. Both boys hated to anger their father—not because they feared him, for he spanked them only once, with a battery cable, but because of their feeling of respect toward him. Even when they were small children, their father had treated them like adults, with consideration and dignity. And always there were rules. “To eat and to bed one should be invited only once,” Cecilio would say. And only once would he have to order his sons to the dinner table or to the bedroom. Words of rebuke were rare. Cecilio, like his father before him, disciplined with his eyes.

Cecilio, Rose, and the children worked hard to keep hunger away and to stay together during the Depression and the early years of World War II. Both boys learned to cook, clean, wash, and sew. Rose taught them kitchen secrets: Starch not only made collars stiff but could be used as paste for kites and papier-mâché piñatas and masks, or to soothe sore feet, diaper rash, heat rash, and poison-ivy itch. Nutmeg, ground pecans, sugar, and shortening, rolled into marble-size balls, loosened the bowels and cured stomachache. Salt was a mouthwash, toothpaste, and sore-throat gargle, and relieved tired feet. Pork lard gave refried beans and flour tortillas a special flavor and also removed chewing gum from hair. Coal oil was used not only for heating and cooking but also as an insecticide. Cecilio taught them to have pride in themselves, never to scavenge in garbage cans or at the city dump for food as many children did, and never to forget their culture. It was unheard-of for a Mexican to deny his heritage or to change his last name—as so many immigrants from other countries had done.

Richard and Cecil did not think of themselves as poor. Everyone on the West Side lived as they did or worse. Only when Cecilio and Rose took the family downtown for Fiesta or north through Alamo Heights to visit a friend who worked at the Longhorn Cement Plant did they see wide, grass-covered yards, shiny cars, curbed and paved streets, tennis courts, and, more than anything, hordes of white faces. Both boys had encountered Anglos mostly as teachers. Of course, there was the oil salesman who always came around to the garage in a very clean blue suit and white shirt, meticulously cleaning his nails while Cecilio, covered with grease, made polite conversation. Many whites lived in the Prospect Hill neighborhood just north of the barrio, but Richard and Cecil were not allowed to wander that far from home.

In the forties Cecilio decided to move his family and business to a strip of property one block south of the family homestead. More than once burglars had broken into the station and taken tools and auto parts, and he wanted to be closer to it. Pedro and Rose agreed, so Cecilio put down $200 on a tapered 90-foot-by-330-foot piece of land overlooking Apache Creek. He would pay the remaining $1000 of the cost in monthly installments. His sisters and father remained across the creek in the old houses near their familiar neighbors: Don López, who barbecued sheep heads in an outside concrete oven and peddled them downtown, coming home slightly drunk most nights and roaring like a lion to keep his many children and his wife away so he could sleep; two former “chili queens” who had sold chili on Military Plaza a few years before; a strange, quiet man who sat in front of his home all day in his taxi and later died of tuberculosis; and a family of migrant workers who left each spring and returned in the late fall with their truck radiator full of butterflies, usually poorer and looking as ragged as their front yard.

Richard and Cecil visited their aunts and Pedro across the creek every day. Cecilio worked on cars, and Pedro dispensed gas and sold beer-to-go in a part of the garage that had been remodeled as a small cantina. Workers from the nearby packinghouses and stockyards would snap down their quarters for three beers, stretching in their white coats streaked with animal blood and relaxing under the trees before returning to work. They would surround Cecilio and watch him solve auto malfunctions, murmuring, “Aquí tenemos un misterio. We have a mystery here,” as he listened and tinkered and tightened.

Cecil had taken a job at Sommers Drug Store as a delivery boy. (On his first delivery he hit the pharmacist’s car with his motorcycle.) Always the extrovert, he was popular in school. He had the appetite of a zopilote, a buzzard, and managed to be first in line each Wednesday for the enchiladas. Occasionally he was given licks with a paddle for excessive fidgeting—jumping around, talking, organizing—but they were nothing compared to his memory of Cecilio’s battery cable. In 1946, after a year and a half at Sidney Lanier High, Cecil and a group of friends quit school and joined the Navy.

Richard graduated from Lanier High and entered San Antonio College the year Cecil set sail for the Caribbean on his destroyer. On November 16, 1950, five months after the beginning of the Korean War, Richard joined the Air Force to become a pilot, thus continuing his lifelong love affair with aircraft. During the war he was stationed at Ellington Air Force Base near Houston, where he studied navigation after washing out of pilot training. He would stay in the service for twenty years, almost all of that time in the Strategic Air Command.

That Old Gang of Mine

As the years went by, Cecilio could feel the changes in his family. Mama Rose had learned in school to speak, write, and read English, but he had not. This knowledge increased her importance in the household far beyond the strictly maternal role of women in the village. It meant that she, not he, was the emissary to downtown San Antonio, the purchaser, the interpreter of laws and forms, the person who dealt with city officials. To make extra money, she began working in the house as a seamstress, and during the pecan season she organized a group of women to shell pecans in the back yard. Cecilio would hand over his money, and Rose would draw up the family budget. A family pattern had changed in one generation. Families of Pedro’s generation mostly kept to the old customs, because they provided a familiar comfort in a strange land: the extended family close by, retaining the Mexican language, food, religious rituals, and child-rearing customs. Such concepts as coed schools and freedom for young daughters were directly opposed to every precept of moral, upright living brought by the first-generation male from Mexico. In barrio homes like Cecilio and Rose Martínez’s one could find all degrees of adjustment to the new or clinging to the old, but each family, some faintly, some pronouncedly, had embraced America.

In World War II, battalions of sons and husbands left the West Side to fight for an America most knew little about. Their departure loosened some of the strongest bonds to the old village life. Almost overnight, bars and dime-a-dance halls opened along Guadalupe and El Paso streets, filled with part-time pimps, raunchy music, and soldiers lured to the West Side by barrack tales of easy women. During these fevered years the layers of innocence and isolation were peeled away from El West Side like the skin of an onion.

For the first time, women left their young children with an older son or daughter and went to seek the good times on Guadalupe. The promise of escape beckoned them, a short hitchhike to an illusionary heaven far away from the cramped apartments, poverty, demanding children, and loneliness. The ancianos, the elders, noted what was happening and clucked their tongues: “She is going around loose, like a burro without a rope. She is queen of the cattle bins. She says she has a good family, but her house is filthy.” A verse of a corrido, a ballad about barrio life sung at the time by conjunto bands, told of the momentous change:

Even my old woman has changed on me—

She wears a bobtailed dress of silk,

Goes about painted like a piñata,

And goes all night to the dancing hall.

I’m going back to Michoacán—

As a parting memory I leave the old woman

To see if someone else wants to burden himself.

There were always flowers in the barrio during the forties, flowers for funerals and from lovers, flowers to help the ones left behind to forget the war, and flowers for the husbands and sons who disappeared, leaving only their names on headstones. Since ancient times, flowers had held religious meaning for Latinos, symbolizing the passing of life: from the seed, which is nothing, comes the resurrection, the flower. The old life, the seed, must die for the new life to come.

The boys too young to go to war went to work racking balls in pool halls, selling newspapers, shining shoes, setting pins in bowling alleys, or selling flowers at San Fernando Cemetery, wiping the cans clean and reselling them to florists. For them, also, the street life became an escape and a search for identity. In the tradition-laden barrio the riptide of change was eroding the foundations of the family, which was the foundation of the barrio itself.

One of the results of this wartime upheaval, of the loosening of family ties and the absence of fathers, was the emergence of gangs on the West Side: kids with hard, dead looks, thin mustaches, and pointed tangerine shoes, street-wise kids who had grown into manhood with pompadours and arms engraved with scars or tattoos of the Virgin of Guadalupe, of serpents, skulls, or the pachuco cross with three dots representing the Holy Trinity. Idleness seemed to strop their anger. Each gang had its own slang, rules, nicknames, and girlfriends. There were complex rituals and alliances: the Espiga gang warred with the Riverside boys, and the Red Light and Cassiano gangs had a temporary truce with the Lake gang that claimed Elmendorf Lake as its turf. The oldest barrio gangs—the Alto and Ghost Town groups—had many subgroups, like the San Patricio Alley boys and the Roy’s Drive In crowd.

Each gang fought to be the most feared. Each established its own territory, using a railroad track, creek, street, or park as its particular border. The Tripa gang headquartered near the packinghouses, the Las Palmas gang at the shopping center of the same name, and the El Con gang at a grocery store on El Paso Street that had a huge ice cream cone sign. Barrio residents had only to read the walls to learn what gang held that turf and who its leaders were. First would appear a member’s name or nickname; then the gang name itself, sometimes with C/S for con safos (the same to you) or rifan (the best or the toughest); and then thirteen dots, the letter M, or C13M (all referring to marijuana, M being the thirteenth letter of the alphabet). This gang graffiti would appear on the walls of rest rooms, bus stops, schools, housing projects, phone booths, dance halls, and neighborhood garages.

There was no specific type of gang member. They were young men from thirteen to twenty-one who hungered for status and recognition or wanted to prove themselves as men in the same way their older brothers had. Usually they drifted together naturally, seeking the support that their schools, homes, and churches had failed to provide. They gathered to drink, steal, fight, vandalize, and buy drugs. They were curbstone experts on sex (“She’s bowlegged; I bet she’s done it already”). They embodied the celebrated Mexican machismo in which sex was viewed as aggression, but behind this attitude usually lurked feelings of insecurity, defensiveness, and insufficiency. The favorite weapon of the gangs was the switchblade knife; it was much more macho than a pistol because you had to face your enemy up close, perhaps to catch his blood, or he yours. In rumbles, gang members fought with bicycle chains, clubs, baseball bats, weighted pool cues, and zip guns.

Only the kids trafficking in narcotics used guns in the early days of the gangs. They would deliver a rubber-band-wrapped bundle of 25 marijuana joints to the Cinco de Mayo or Villa Rosa Bar to be sold for $5; or a “finger stall,” a balloon, prophylactic, or rubber finger-protector filled with heroin. Heroin was the preferred drug to sell: it was more lucrative and easier to get rid of in case of trouble. They sold all four colors: gray, white, brown, and pinkish. Brown caused an intense itching sensation at first. White had the longest-lasting effect. But an old shot-in-the-arm junkie who was coming down—eyes watering, yawning, nose running—who brought out his eyedropper and needle and, if not a tablespoon, a soda-pop bottle cap, who never had his piece of cotton filter and had to scrape a small amount of fiber from the tongue of his shoe—he preferred the gray. It hit the bloodstream with the flash-bang of a skyrocket, and suddenly the body no longer felt it had death’s fingerprints all over it. More than anything else, drugs ate away at the foundation of the barrio. They were the solvent, the seducer, the escape, the destroyer of the old ways.

In the fifties the “scorpions,” men feared for their sting and aggressive behavior, moved in and took over the heroin market. Edged out of the drug trade, kids nicknamed gasofas soon discovered a new craze, sniffing gas and lighter fluid. Others turned to shoplifting, fencing their goods at pawnshops along Commerce, Laredo, and Zarzamora streets.

While gangs occasionally warred over narcotics dealings, the main battles were territorial. The Dot and Circle gangs fought over Concepción Swimming Pool near the missions; second-generation Alto and Ghost Town gang members fought for control of Cassiano Park, and half a dozen gangs vied for the Elmendorf Lake turf. Gangs controlled whole neighborhoods. Playgrounds and school dances became battlegrounds. Boys wouldn’t date girls from certain neighborhoods for fear of being beaten, or if they did, they called ahead and told their girlfriends to have the door open. Neighborhood newcomers were harassed and often beaten if they refused to join the gang. Churches couldn’t hold night meetings. Darkness literally descended upon the barrio as the gangs continually knocked out the streetlights.

Who was to blame? Some in the community blamed the public housing authorities; the housing officials blamed the older barrio residents for tolerating the gangs; school authorities blamed the community centers for pampering the gang members; the centers blamed the schools for adding to the gangs’ numbers by expelling troublesome students. The police blamed the housing managers because most of their calls came from the projects; and the tenants of the projects blamed the police for using excessive force, the housing managers for being dictators, and the rest of the barrio for not minding its own business.

The outward-directed violence of the gang warfare of the forties and fifties shifted in the next two decades to the inward-directed violence of drug use. Sniffing had changed. Hobby-glue manufacturers had introduced a mustard-seed additive to their product that nauseated anyone who sniffed it. But there was still spray paint. Sprayheads knew the product by color and catalog number—Krylon Spray Paint Interior-Exterior Enamel Rust Magic. The favorite was Bright Silver, number 1401. Metallic colors were popular—gold, bronze, copper, silver—all sweet-smelling depressants that produced a twenty- or thirty-minute high similar to inebriation. Earlier, sniffers had sprayed the vapor into a plastic bag, but now it was considered cooler to spray into a soft-drink can so you could walk down the street getting high without attracting attention. Some kids made a living selling spray paint, doling out handkerchief hits for a quarter each.

The social workers at the Mexican American Neighborhood Civic Organization (MANCO) tried hard to cut down the sniffing. They had some success, most notably with two kids, Eddie “Bo” Cerros and Jeffery Acosta, from the Cassiano and San Juan public housing projects. With MANCO’s assistance, these boys made an amateurish but effective movie, El Juanío, that dramatized the world of the sprayhead. They had all come from broken homes, had dropped out of school, and had working mothers and many brothers and sisters. Like many ex-sprayheads, they had taken up the habit not only because of peer pressure but also because it temporarily obliterated their fear of not having a future or a job. For a while it wiped out memories of parental battles; it killed hunger for some, heightened sex drives and produced hallucinations for others; and it helped still others forget their anger, a cold winter day without a coat, a long-missing father, or a girlfriend’s betrayal. Bo and Jeffery belonged to the Cassiano gang, a group of about fifteen or twenty friends who would meet after dark at a park west of the projects to smoke weed and discuss the night’s plans. Sometimes they helped Juan and Steve, who were painting the murals that covered the sides of the Cassiano Homes buildings, a series of scenes from Mexican history painted with beautiful earth colors in the tradition of Diego Rivera, Clemente Orozco, and David Siqueiros, Mexico’s great muralists. Murals brightened up many places in the barrio: MANCO headquarters, La Clínica Amistad, a small grocery on Kemper, and Los Arcos Cafe, among others.

Sometimes it seemed to social workers and others attempting to prevent trouble that crime felt at home in the barrio. There was something different to worry about every day. A new gang called the Whistling Warriors had vandalized and burned out some vacant houses on Martin Street and fired bullets through the bedroom windows of some older couples in the neighborhood. These boys modeled themselves after the gang in the movie The Warriors and used an old barrio gang tactic of stationing members in trees to whistle when police or members of other gangs approached. More gang graffiti had appeared on the walls recently: the Lords, the Night Sinners, the Midnight Rats. Burglaries had increased west of the Cassiano Homes—thefts of stereos, irons, toasters, televisions, and radios by junkies. There would always be lawlessness in the barrio, but parents like Cecilio and Rose Martínez, whose children did not join gangs or get to know the inside of the Bexar County jail, still relied on the traditional child-rearing methods of the Mexican village: providing discipline, showing love and concern, assigning chores at home, and treating their children with respect.

The Children of the Dream

In 1953 Cecilio was 54 years old, and for two years he and Mama Rose had been living in a house without children. After returning from the Navy, Cecil had married Delia Gonzales, his high school sweetheart, and now lived a block north across the creek in the Alazan-Apache Courts with his three children: Gloria, three, Walter, two, and the newborn Rosemary. Cecilio and Rose were content and comfortable. Cecilio had never wanted to make a lot of money, just enough to live decently and keep the family together. His health was good, even though his bones ached and warned him of approaching cold weather on late fall evenings.

Cecil had been studying at Saint Mary’s University for three years, working part-time at Pennington Channel Chromium Company and spending his off hours flying the small plane he kept at Lake Field, near Mitchell Lake. As always, he approached life full throttle, working at many jobs: helping run the family cantina, Snuffy’s Tavern (Cecil had been nicknamed Snuffy in elementary school after portraying a character in a school play who resembled the comic strips’ Snuffy Smith); welding; building; and crop spraying. But there was one thing Cecil felt he could not do: keep his marriage together.

Cecilio was aware of his son’s marital troubles. Long ago Pedro had advised him to watch his children’s eyes to know their feelings; therefore Cecilio was not surprised when his son told him Delia was leaving for California. “I have searched my soul and worked to save this marriage, but it is not to be,” Cecil told his father. He said he could work in Central America with the airplane—crop spraying and servicing aircraft engines—and Delia had a good job waiting for her in Los Angeles. The question, however, was what about the children? Everyone agreed they could not go with either parent, and placing them in a foster home or with strangers was unthinkable. Cecilio and Rose were the obvious choice. But as much as they felt their responsibility in this matter, they had doubts.

“Can we at this age raise another family? Where is the room, the money to raise three babies and send them to school?” asked Mama Rose. Cecilio didn’t argue with his wife. They had been married 27 years, and he knew that she could always best him with words. He merely said, “All right, we will turn them out on the street or give them up to strangers,” knowing that Mama Rose would see they had no choice. And so Cecilio and Rose began raising a new family, the fourth generation of Martínezes in America, in their small house behind the cantina and garage on Brazos Street, across the creek from the old homestead where they had started on their own during World War I. Change would come, but the family would survive. Pedro, the great-grandfather of Walter, Gloria, and Rosemary, had the last word: “Todos hijos de Dios o todos hijos del diablo”—whether we are all children of God or of the devil—“we will stay together.”

The arrival of the three children meant that everyone worked harder. Cecilio worked longer hours in the garage and cantina. Pedro served the customers. Mama Rose ran the house and made the clothes. The old dicho describing the lazy ones in the barrio—“He sleeps until his belly button swells”—applied to no one in the Martínez family. The long hours and hard work took their toll. In 1955, when his great-grandson Walter was four, Pedro had a heart attack at the garage and died soon after. He was 84. The family grieved. The old patriarch had not only brought them to the new land so many years ago but had also brought the traditions and customs, the heritage of their ancestors, and the wisdom that the family was the basis of society. He had believed that life was a gift and, because it came from the Creator, a mystery. He had accepted the totality of life, both joy and suffering, for to live is to know conflict and experience pain.

Walter Martínez grew up a responsible boy, looking after his two sisters, helping Mama Rose with the cleaning and tortilla making, and, on wash day, working the old machine that sat out back, with its rollers and swish-swish innards. Cecilio never went downtown, so Walter accompanied his grandmother, with her lists and newspapers and shopping specials, to Solo Serve to buy household goods and clothes and fabric for her sewing. On his ninth birthday he got his first toolbox and started helping Cecilio with tune-ups, brake jobs, and minor tinkering. When his grandfather was running the cantina, Walter would often poke his head into the room and ask Cecilio if he needed a sandwich. The workers would always laugh and say, “Mira el ratoncito. Look at the little mouse,” referring to Walter’s prominent ears.

Few friends came to visit. The Martínez property was isolated between the creek and packinghouses. Walter played games with his cousins and sisters: making kites with Sunday comics and homemade glue; tossing washers into buried tin cans, a barrio version of horseshoes; making slingshots from Y-shaped branches and inner-tube rubber, with shoe leather for the pouch. And like the past three generations of Martínezes, he went to the Saturday-afternoon movies.

Cecilio taught him to live for the present, one day at a time. It was a good way to live when you didn’t have much, since it meant taking great pleasure in the awareness of small things, such as supper time, when the long afternoon of chores and school was done and his grandfather would sit at the head of the table and say, “A ver si pasa. See if it passes.” No one, not even the oldest aunt or cousin, could remember anything not passing down Cecilio’s throat: the guisados, beans, peppers, caldos, tortillas, tacos, even the guisado called morcilla, made from blood, that is still served in tacos at the Piedras Negras Restaurant on Laredo Street. Walter’s older sister, Gloria, sat closest to Cecilio. She had a speech impediment and received special attention from her grandparents. Rosemary, the younger sister, the feisty one, was self-reliant, spoke her mind, and had been a rebel since her youngest days. She sat at the other end, usually wrangling with Mama Rose.

Birthdays were always observed with a cake, special Mexican hot chocolate stirred with a molino, a gathering of cousins and aunts, and a few gifts, usually something useful—a new shirt made by Mama Rose, some tools. There would also be a piñata. The religious aunts explained that the piñata custom was begun in Guanajuato by the Franciscans, that the papier-mâché figure was the devil within you that is not seen—hence the blindfold—and you must strike him with the rod of virtue. If you persevered in this battle against evil, you would be showered with the glory of God (as well as with candies, in which the children seemed to show more interest).

Once a month the family would travel to La Coste, close to Castroville in nearby Medina County, to the shrine of El Niño Perdido (the Lost Child) to pray for an end to the pain in Mama Rose’s chest and shoulders. This Sunday picnic-pilgrimage was like a holiday, the only time the family left the barrio together: Cecilio driving the old sharp-nosed Studebaker; Mama Rose with the food; in the back seat, Walter and his sisters and usually one of the devout aunts fingering her knotted beads on silver wire. As Indians made pilgrimages to the Hill of Tepeyac, where the Virgin of Guadalupe had appeared to the Indian Juan Diego in 1531, so barrio families made trips to shrines honoring saints like San Martín de Porres, a humble mulatto who loved the poor, whose shrine is in Weslaco; El Señor de los Milagros (the Lord of the Miracles), whose shrine is near El West Side; or Nuestra Señora de Juan de los Lagos, whose shrine is in San Juan, Texas. There is even a shrine in Falfurrias honoring the famous curandero (healer) Don Pedro Jaramillo.

The saints serve to individualize abstract religious teachings. Saint Anthony is the patron saint of San Antonio, Saint Jude the patron saint of hopeless causes. San Martín Caballero was a pagan Roman soldier who became a Christian and dedicated his life to preaching the gospel to the poor. Many barrio businesses have his image placed near their front doors as a reminder to treat the poor with respect. Almost every barrio home has a family shrine, usually in the living room, where pictures of the deceased and the saints, flickering candles, and sometimes milagritos—gold, silver, or bronze charms of parts of the body—are all grouped together. Many homes have yard shrines to Our Lady of Guadalupe, surrounded by plastic roses (when the Virgin appeared to Juan Diego she gave him roses) and lighted at night.

A Personal Destiny

Like his father, Walter attended Sidney Lanier High School and worked at a pharmacy after school, a job Cecil got him through his friend Jesse Camacho, who owned Dellmar Pharmacy. In his junior year Walter participated in the one militant activity at Lanier during the tempestuous sixties, a sit-in to call attention to student demands for an end to the ban on speaking Spanish, more college-oriented and fewer vocational-technical courses, and more Mexican American teachers. The students held a press conference at Our Lady of Guadalupe Church and were partially successful in getting changes adopted: students could speak Spanish but not in the presence of a teacher.

Walter Martínez had no problem keeping out of trouble. There wasn’t much time left after participating in school activities, working at the pharmacy, and helping Cecilio repair cars, getting his hands black with grease and oil, his neck and wrists noosed with dirt from the dust raised by trucks delivering cattle and pigs to the slaughterhouse scarcely a hundred feet from their house. Walter loved high school. He had many friends, felt comfortable there, made acceptable grades. He decided to stay another year instead of graduating with the class of 1969. Cecilio and Mama Rose understood. More than anything, he wanted them both to see him graduate in the spring of the new decade, May 1970.

The Christmas of 1969 was a good one. Most of the family gathered for this special holiday, the one time during the year when everyone came to the old home for a big dinner, holiday tamales, and Mexican hot chocolate. Walter’s sister Rosemary came from California where she was living with her mother. Gloria, his other sister, arrived from Chicago, where she had been working and was about to be married. His mother visited and brought gifts, as did Cecil. The remaining aunts, uncles, and cousins dropped by. Everyone agreed it had been a good year.

Walter was awakened at one in the morning a few nights after Christmas by Mama Rose, breathing heavily and complaining of a sharp pain near her heart. She was sitting on the couch in the darkened living room, her bent body outlined by the flickering candles near the saints on the mantel above. Cecilio was sick, so Walter put her in the Hillman Huskie station wagon for the trip to Lutheran General Hospital on Zarzamora Street, a mile or so west. The cold air burned in his throat as he started the car and raced to the hospital. The nurse on duty wouldn’t take Mama Rose. “No emergency room, no doctor here right now, you must try Baptist Memorial Hospital downtown.” Another nurse realized that Mama Rose’s condition was critical and rode with Walter down Buena Vista Street, giving her mouth-to-mouth resuscitation. He ran a red light and picked up a policeman who led the way to the emergency room at Baptist, lights flashing, sirens wailing. Baptist’s admitting nurse said they had to wait. Walter and the policeman grabbed a stretcher, the nurse from Lutheran called the orderlies, but Mama Rose lost consciousness along the way and was in a coma. The last thing she had seen in her life was the streetlights on Buena Vista flashing by in the cold December night. Mama Rose, Cecilio’s wife of 43 years and the woman Walter considered his real mother, died 72 hours later, on New Year’s Eve.

It was Cecil who determined the direction of his son’s life after Mama Rose’s death. After graduating from Lanier, Walter and his friend Willie Martínez attended Tulane University on a grant-scholarship arranged by Cecil, but Walter returned to the West Side after one semester, still shaken by his grandmother’s death. In 1972 a friend of Cecil’s, attorney Joe Hernández, decided to run for the state legislative seat representing the West Side. Cecil managed the campaign and asked Walter to help. Walter found he loved the organizational work, the rallies and debates, the nuts and bolts of campaigning. His enthusiasm and sincerity overcame his shyness. People listened to him, and he discovered he enjoyed trying to persuade strangers to vote for his candidate. After Hernández’s victory Walter became his administrative assistant, commuting to Austin daily during the 1973 legislative session and running the Democrat’s small district office on Buena Vista Street behind Centeno’s Supermarket. Walter wanted his lifework to be politics; he wanted to work within the political system to improve conditions on El West Side. He would prove the error of what the younger ones said, that the only good system is the San Antonio sewer system and even it is clogged up most of the time.

The Other Minority

Until recently efforts to improve the lives of Mexican Americans have been feeble. They share with blacks the disadvantages of economic insecurity and discrimination. The Mexicans brought with them three things that insured prejudice: a different-colored skin, a foreign language, and an unpopular religion. In general they have had little representation at any level of government. They fall well below other minorities on almost every measure of acculturation. In educational attainment Mexican Americans rank substantially lower than blacks and way below Asians. Their family incomes are higher than those of blacks, but their per capita income is far lower, a consequence of high fertility rates and large families.

Ironically, despite the miserably poor living conditions and the isolation of its Mexican American population, San Antonio has many more appointed and elected Mexican American officials in local and state offices than Los Angeles or any other city in America. Two groups on the West Side are largely responsible for this phenomenon: the Catholic Church and an activist organization, Communities Organized for Public Service (COPS), that headquarters 29 of its 32 chapters in churches.

Almost from the beginning, social activism and the Catholic Church have been one and the same in the San Antonio barrio. The area was colonized by religious orders—Augustinians, Jesuits, Oblates, Claretians—who were interested in using the Church to better their parishioners’ lives on earth, a tradition that reaches back to the Franciscan missionaries who arrived in Mexico in the sixteenth century. This goal is quite different from the traditional Catholic emphasis on giving the sacraments, saving souls, and combating personal rather than institutional evil. Often in the past the Church had preached that poverty was a virtue, not something to be ashamed of. The more one suffered, the greater one’s chance to enter heaven. The need to suffer was inside the soul, like a bird pecking away inside an egg. Si Dios quiere (if God wills it) was a credo followed by many on the West Side. But their priests embraced a more liberal theology, based on their conception of Jesus Christ as the liberator who had confronted all forms of institutional and personal oppression, domination, and injustice.

Many West Side priests take an active role in secular affairs: for example, Father Edmundo Rodriguez of Our Lady of Guadalupe is a founder of COPS, and Father Albert Benevides, pastor at St. Mary Magdalen’s, grew up in a West Side housing project as one of six sons of a packinghouse worker, and also works with COPS. San Antonio’s first Mexican American archbishop, the spiritual leader of 550,000 South Texas Catholics, is Patrick Flores, son of migrant farm workers from Ganado and an outspoken leader in social causes. Before being named archbishop, Flores served as auxiliary bishop at Immaculate Conception, one of the churches in the West Side Coalition, a group of six parishes that work with COPS to solve neighborhood problems. Over the past five years they have won many battles to improve the physical landscape on the West Side and inner city. Now COPS and the churches are working with the San Antonio Development Agency (SADA) to build 120 new homes on the West Side in Colonia Santa Cruz, an old neighborhood near Our Lady of Guadalupe Church. Homes also will be built or rehabilitated in three more colonias: Amistad, Concepción, and St. Alphonsus. The corrales and shotgun shacks will be replaced with houses. West Side groups have gotten Apache Creek cleaned up and rechanneled, built parks, and opened a badly needed clinic. They are working to get a police substation and more police officers for the West Side.

Despite the poverty, the unpaved streets, the crowding of houses onto a single lot, the West Side has never been a slum. The barrio has its stark landscapes: weedy, dangerous vacant lots choked with garbage and roamed by half-starved, unleashed dogs; water-filled ditches and sumps; burned-out buildings hiding tramps and junkies; and perilous bars like El Molino near Lanier High School. But the West Side also has shady streets, porches full of houseplants, narrow lawns enclosed by rickety fences, and the full-blown street life of children playing, families holding barbecues, and men home from work visiting with their wives on front porches, all lending a villagelike quality to the area.

There are still street vendors—knife sharpeners; egg sellers; men who pick popular street corners to sell corn on the cob, tamales, fruit, and snow cones (raspas) out of the backs of their trucks. Not all the vendors are men. Every afternoon Mama Tía parks her station wagon behind the Cassiano Homes project and opens a small grocery store in the back of her car, selling sausages, fruits, vegetables, cigarettes, and soft drinks.

Aside from the new homes being built in the colonias and the greater number of paved streets, the West Side barrio has altered little in forty years. The huge produce market moved from downtown to Zarzamora and Laredo streets in the late fifties. Although a few Anglo fast-food businesses now dot the area, virtually no other new industry has moved into the barrio to provide needed jobs. But this situation may change. SADA and some city officials are currently pushing for an urban renewal project, called Vista Verde, to redevelop the east end of the barrio and bring in new industries.

Home at Last

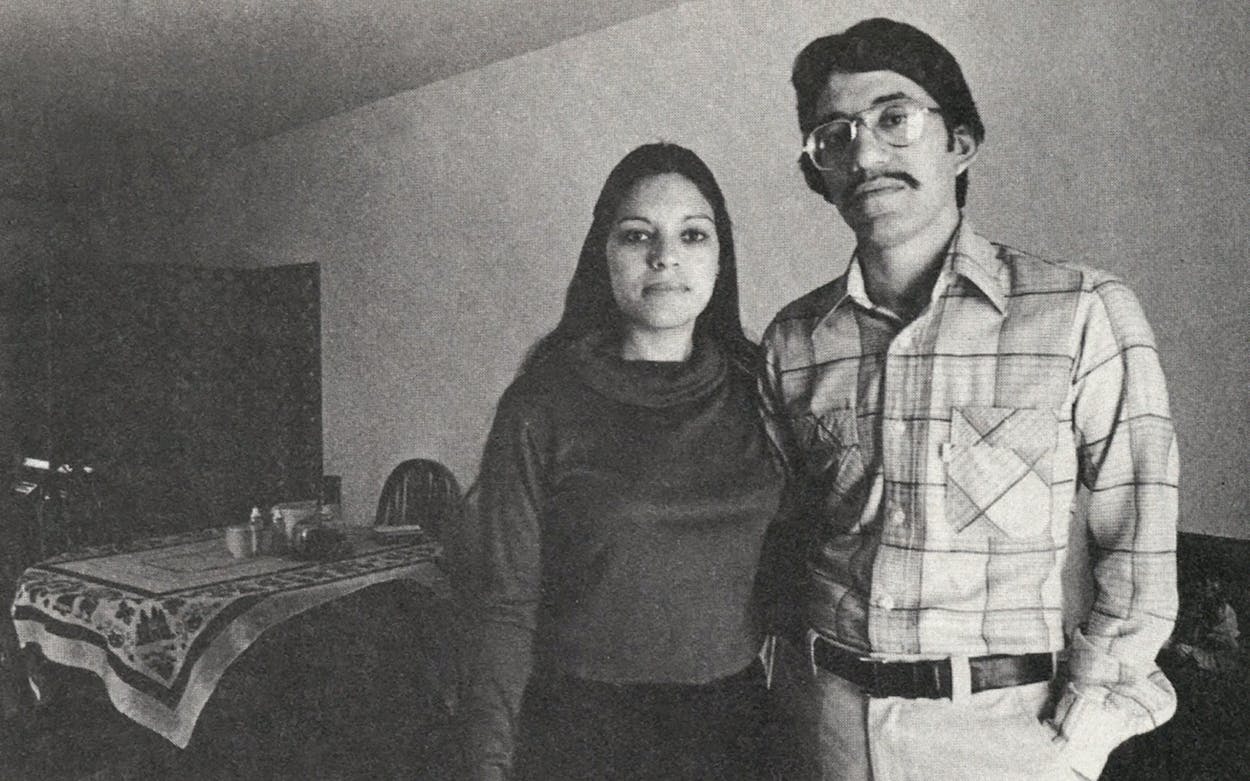

By the mid-seventies Walter Martínez’s life had kicked into high gear. While working for Joe Hernández he was attending San Antonio College and serving in several political organizations. In 1979, after a six-year courtship, he married Martha De La Cruz, a beautiful girl who had grown up in the Alazan-Apache Courts, where her mother, grandmother, and four sisters and brothers still lived. Walter had known her brothers, Joe and Romaldo, in high school and had noticed Martha at their house. Her father had been a laborer and twice had driven all nine of them to Wisconsin and Minnesota to pick sugar beets and potatoes. Walter was a careful young man, responsible and cautious. He and Martha had meticulously planned their wedding so it would not conflict with school, career, campaigns, or legislative sessions.

In Walter, four generations of the Martínez family had produced a man who knew the American way of life well enough to become a seasoned politician, just as Irish families had done in Boston. He was developing sophisticated political skills to use in dealing with Anglos and Mexican Americans; he was neither a radical nor a pawn for the Anglo powers downtown (known as a “Tío Taco,” Uncle Taco, or a “coconut,” white on the inside, brown on the outside). He had learned from another Mexican American politician, city councilman Henry Cisneros, who had been born and still lived on the West Side and was one of the best Latin politicians in the country. Cisneros successfully worked for the betterment of El West Side yet coexisted with conservative Anglos who cared little for his barrio or the people who lived there.

Walter and Martha will lead lives far different from those of Pedro or Cecilio. They are committed to the American ideals of independence, competition, efficiency, success, the pursuit of excellence. They feel, like most Americans, that life is to be enjoyed rather than endured. They have many Anglo friends. The Church does not assume for them the importance it did for previous generations; they have carefully planned the size of their future family. Yet much of the traditional culture and heritage brought by their forebears from Mexico remains and will always be a part of their lives. Martha and Walter’s road runs through both worlds, a blending of the two cultures, a twining together of the American and Mexican styles of life.