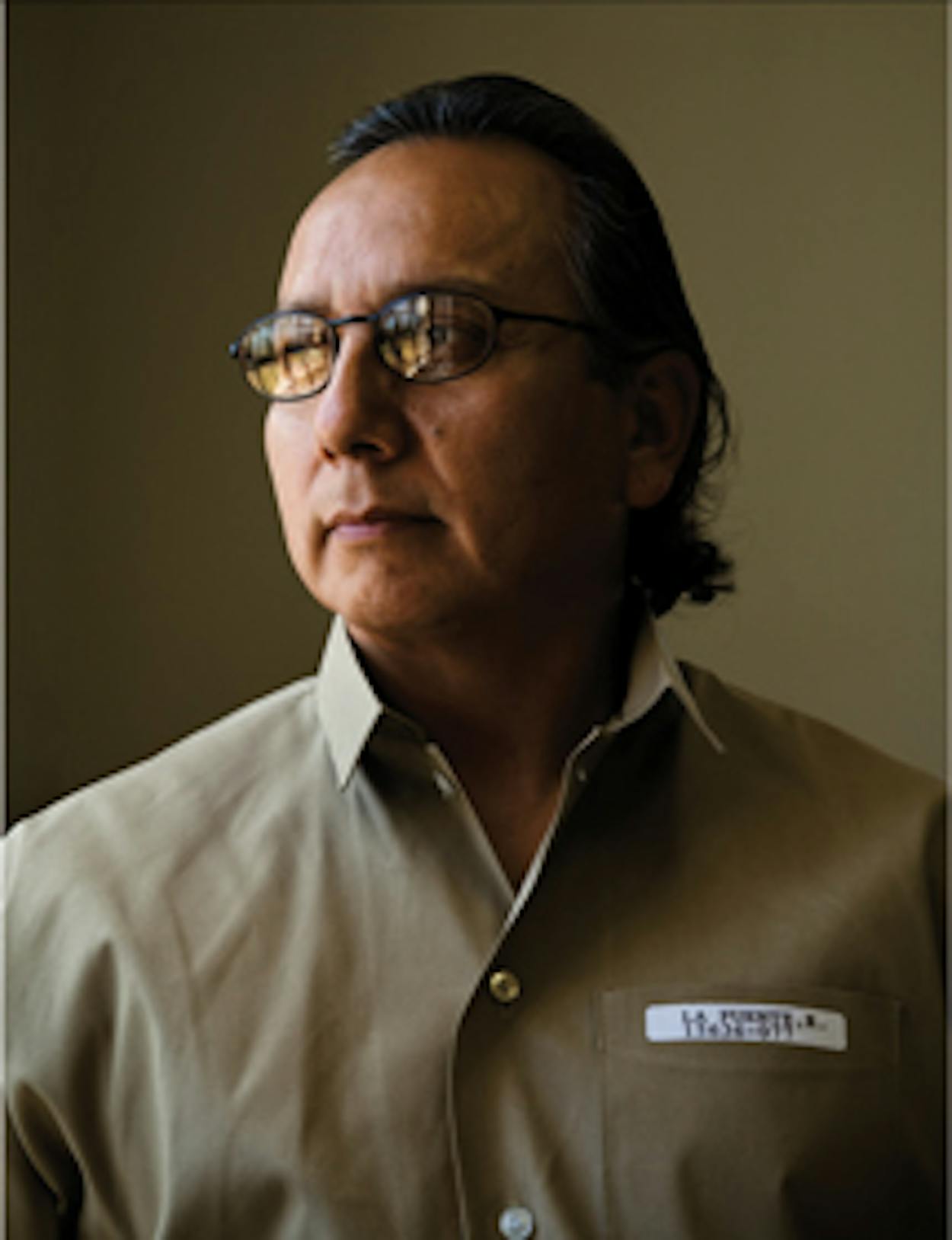

Richard LaFuente has had plenty of opportunities to leave federal prison and go back to Plainview. All he had to do was confess to a murder on the Devils Lake Sioux reservation in North Dakota, for which he was convicted in 1986, and show a little remorse. The first time he refused was at a 1994 court hearing. “I can’t show remorse,” he told his attorney. “I won’t ask forgiveness for something I didn’t do.” He went back to his cell. For the next seventeen years, at six parole hearings (the latest in June 2011), LaFuente refused to confess and show remorse, and each time he was sent back to his cell.

Julie Jonas has had plenty of opportunities to walk away from LaFuente’s case. Jonas is the managing attorney for the Innocence Project of Minnesota, which has worked on behalf of LaFuente, 54, since 2004, along with hundreds of other prisoners who have claimed they were innocent. LaFuente, she said, is different. “I don’t think I have met one who would turn down a deal to get out of prison after eight years in a federal penitentiary, much less one who would continue to deny his guilt even though it meant his parole would be denied after serving 25 years in prison,” she said. “The system keeps asking him to apologize for something he did not do, and his conscience won’t let him do that.”

Lawyers who work for innocence projects are a particular breed of optimist, and Jonas has tried a number of ways to get relief for her client. Her latest attempt is a second petition for executive clemency, which she will be able to file on November 19, one year after the first (which was filed in 2008) was denied. Clemency, in the form of a commutation of sentence, is extremely difficult to obtain. President Obama has granted one in four years in office. (President George W. Bush gave eleven and President Bill Clinton 61.) Jonas plans to emphasize that LaFuente, who is half Mexican American, half Sioux, has been a model prisoner without a disciplinary infraction. He is a father and grandfather. He has a job and a home waiting for him in Texas. “He’s worthy,” Jonas said. “Beside all that, he’s innocent.”

LaFuente was 25 in the summer of 1983 when he and his brother-in-law, John Perez, left Plainview to visit relatives on the Devils Lake Sioux reservation. During that time, a former policeman named Eddie Peltier was found dead on a rural highway, apparently the victim of a hit-and-run. In 1985 LaFuente and Perez, who had returned to Texas, plus nine local Native Americans were arrested for Peltier’s murder after four witnesses said they had seen a mob beat him at a party; one swore she had seen LaFuente, with Perez’s help, run Peltier over with his El Camino. There was no physical evidence, and every defendant but one had an alibi. Nonetheless, all eleven were found guilty. The two Texans were given the longest sentences: twenty years for Perez and life for LaFuente.

Soon, though, details began to emerge that conflicted with court testimony. Stories about the party and the fight turned out to be fabrications. Two witnesses recanted and said they had been threatened by James Yankton, a police officer with the Bureau of Indian Affairs. By 1989, the convictions of nine of the defendants had been overturned for insufficient evidence. Perez was paroled in 1999. Only LaFuente remains in prison, steadfastly maintaining his innocence.

Twice a federal court has ruled that LaFuente should be given a new trial because the first one was unfair; both decisions were overruled. The victim’s own mother, brother and sister have told parole officials that they believe LaFuente is innocent. “I have never worked on a case where the victim’s family was certain the wrong man was in prison,” Jonas said.

And now Hollywood has taken notice. Earlier this year the story came to the attention of Todd Trotter, a Los Angeles television writer and documentary filmmaker. He began tracking down police and FBI files and found a recording of a woman who claimed she witnessed Peltier’s murder. The closer Trotter looked, the more LaFuente’s story seemed to be a classic tale of wrongful conviction.

Trotter talked with two dozen people involved in the case, asking them to agree to be interviewed on camera. He was granted permission to use Robbie Robertson’s “Coyote Song” in the promotional video. He came up with a title, Incident at Devils Lake. All he needed was money to start filming. So in September he started a campaign at Kickstarter.com to raise startup funding for the documentary. If he is successful—he is aiming for $50,000 in pledges by November 14—he hopes to start production early next year.

Trotter has had some fundraising help from an unlikely source: the victim’s sister, Andrea Peltier. Nearly every day since October 19, Andrea has stood outside the Devils Lake Walmart holding a large sign with the word “Fundraising” and photos of her brother and LaFuente. She asks shoppers to donate to the film and has collected more than $1,000 so far.

“I stand out here no matter how cold it is,” she said by cellphone on a cold October morning. “I want justice for my brother,” she said. “It’s been too long. Eddie’s spirit won’t be able to cross over until the right ones are caught. And I want to get Richard out of prison. He didn’t do it—he had nothing to do with it.”