The big first baseman watched the curve ball break across the plate and knew he was out. He even started to leave the plate, and news reports recorded that he smiled when the umpire gave him a reprieve.

The assembled 5000 partisans at Clark Field on The University of Texas campus voiced their displeasure, some looking nervously at the short right field fence an inviting 300 feet away. The menacing figure in the batter’s box had a reputation as something of a slugger, and this was no time to give him a second chance, not after Texas had rallied to tie the game at 6-6 in the ninth inning. But at least the wind was blowing in….

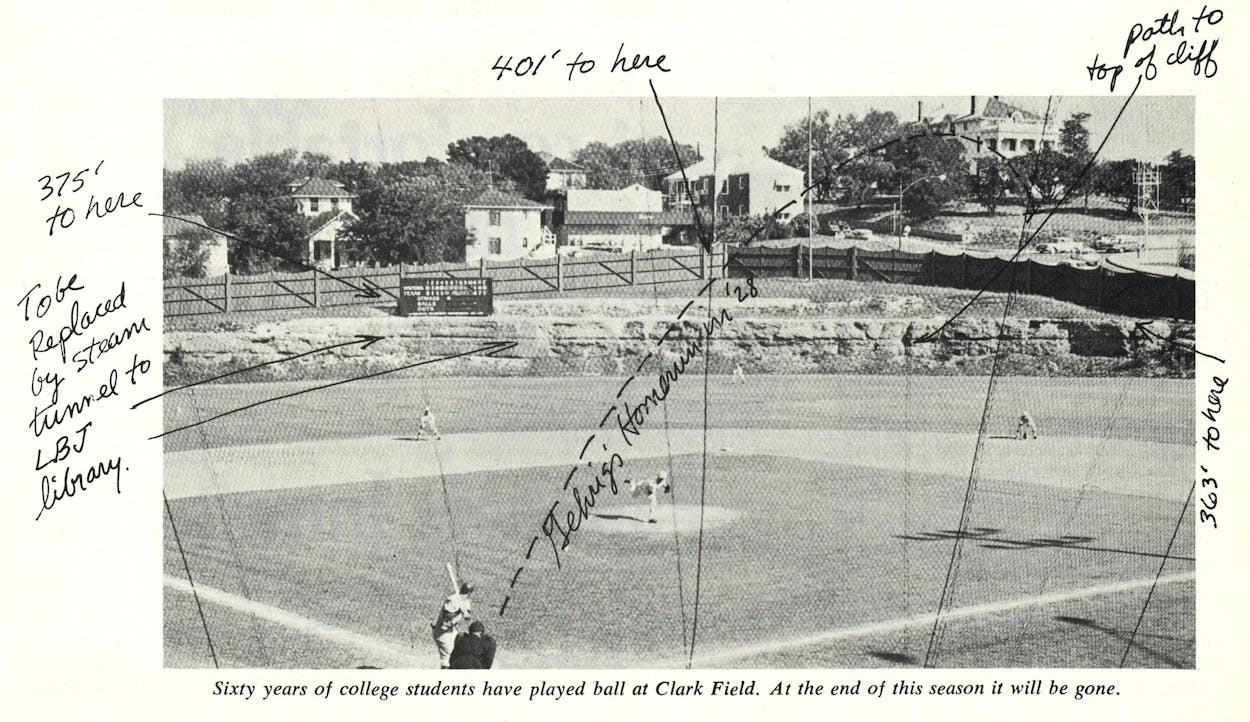

On the mound the Texas pitcher grimly resolved to throw a fast ball past the hitter. It was a poor choice. The batter, who once had worn the uniform of Columbia University but now wore the better known pin stripes of another New York team, judged it perfectly and propelled what the Los Angeles Times was later to call “without a shadow of a doubt, the longest home run ever hit by man since the beginning of baseball.” Lou Gehrig’s bat, which only six months earlier had led the New York Yankees to a four game sweep of the 1928 World Series, had done it again, and the Yankees beat the Texas Longhorns, 8-6.

The ball Gehrig hit soared out of Clark Field over the center field fence, cut a triangle over a street intersection, and finally came to earth more than 600 feet away. Its landing site was halfway up a hill in the spacious front lawn of a fraternity house; legend has it that the ball was still going up when the hill got in the way.

The house and hill are gone now, bulldozed to provide landscaping for Lyndon Johnson’s library. Next year Clark Field itself will be fed to the unsentimental earth-movers to make room for a fine arts center, and with its demise will die not only the last link to The Home Run, but also the most singular athletic playing field in the State of Texas. The Astrodome? Anybody can build a domed stadium; all that takes is money, Clark Field took genius.

The modern ball park is built for symmetry, favoring neither lefthanded nor righthanded batters. This achieves a statistical perfection of sorts but eliminates one of the most appealing aspects of baseball: the living, breathing presence of the physical setting as a dominant factor in the game. All the electronic gadgetry of the Astrodome scoreboard is essentially irrelevant to what happens on the field. But the wall at Fenway Park, the weird rectangular dimensions of the old Polo Grounds with its Little League foul lines and endless center field, the concave right field wall at Ebbetts Field in Brooklyn, and the brick-like infield at Forbes Field in Pittsburgh—these were an integral part of the game; they changed the way the game on the field was played.

Clark Field is not a modern ball park. Symmetry plays no role in its dimensions, which extend 350 feet to the left field wall, 401 feet to deepest center, and angle sharply in to only 300 feet at the right field foul pole. The profile, deep in left and center, short in right, vaguely suggests Yankee Stadium, but there the comparison ends. Clark Field is different from any other baseball park in the world. Some are larger, some smaller; some seat more, some less; some have lights, some don’t—but all are flat. Clark Field is split-level. Other ball parks are divided into infield and outfield; Clark Field is divided into lowlands and uplands.

The dividing line is a 12-foot cliff which sits absurdly in the middle of the outfield. It begins in right center field, angles sharply across center field, and slopes gently down to the left field line where it tapers to little more than an incline. The plateau is 53 feet wide in straightaway center field, 60 feet wide at its widest point, a mere 18 feet wide in left center, and broadens out again to 31 feet at the foul line. Any ball hit on the cliff is in play, although when the collegiate district playoffs were held at Clark Field in 1970, this particular ground rule was a little more than the NCAA could take. Balls hit on the cliff were decreed to be automatic doubles, but Texas won the playoffs anyway.

No one knows exactly why the cliff was left there. Part of the slope was blasted away to provide rock which eventually served to build up the home plate and grandstand area. Perhaps it was too expensive to remove the rest of the cliff, or perhaps someone decided it was picturesque, but whatever the reason, the cliff has plagued visiting teams for 47 years. Texas outfielders are naturally more familiar with the terrain; they often scale the walls like lizards to hold enemy batters to doubles and triples, while Texas batters usually have time to circle the bases before opposing outfielders solve the mysteries of the cliff. A former Texas coach is said to have developed a practice routine of blindfolding his outfielders and timing their ascent to the plateau.

The cliff has contributed to some unusual baseball moments. Two years ago a Texas pitcher was working on a no-hitter late in the game when an opposing batter lofted a deep fly to left field. The Texas left fielder scurried up the slope, tapped his glove confidently, and watched helplessly from his perch as the ball fell just short of the incline on level ground.

Last year the cliff helped a Texas batter attain the dubious distinction of doubling into a double play. With men on first and second, he drove the ball to deep center. The runners stayed close to their bases, not knowing whether the ball would be caught. The enemy center fielder judged the rebound off the limestone perfectly, and the runners tried to make up for lost time. When the confusion ended, Texas had too many men on third base, and two of them were out.

The cliff produced a rare type of home run several years ago. A ball hit over the center fielder’s head appeared destined for higher ground. The left fielder charged up the path to the plateau, intent on holding the batter to a triple. The center fielder went back to the base of the cliff and leaped for the ball. The shortstop raced into center awaiting a relay, and the third baseman covered his base hopefully. They all guessed wrong. The ball hit the top of the bluff, evading the desperate leap of the center fielder, and ricocheted into left field. The closest person to the ball was the runner as he rounded second.

Just as the Boston Red Sox have filled their lineup with right handed power hitters to take advantage of the short left field wall at Fenway Park, Texas baseball teams have been shaped by the character of Clark Field. The short right field fence means that left-handed batters who can pull the ball are always in demand. Right-handed batters must not only overcome the handicap of a deep left field, but also face a fence that is abnormally high because of the cliff—so Texas right-handed batters are usually line-drive hitters. A promising catcher named Bill Berryhill completed three good years at Texas in 1973 but had the misfortune to be right-handed; he had a talent for hitting solid blows that were caught just short of the cliff. If the dimensions of the field had been reversed, he’d hold every Texas home run record.

Clark Field has been a good home for the Longhorns. They have won nine straight Southwest Conference championships, and have won or tied for the SWC title 48 times in 58 years. The cliff has helped, of course, but so have the players: through the years Texas has sent numerous players to the major leagues, including Pinky Higgins, Grady Hatton, Randy Jackson, Murray Wall, and most recently, Chicago Cub pitcher Burt Hooten. Bobby Layne led Texas to four straight conference championships but chose pro football. The next Texas player to reach the major leagues will probably be David Chalk, who has a chance to win the starting shortstop job for the California Angels this spring.

Future Texas major league prospects will play in a $2 million stadium under construction in East Austin more than a mile from the main campus. It will have a seating capacity of more than 5000, plus an artificial playing surface, lights for night baseball, and an electric scoreboard. The field will be one of the premier college baseball stadiums in the nation, comparable to new parks at Southern California and Arizona State, the schools Texas annually contests for the College World Series championship in Omaha, Nebraska. Like all the new ball parks, it strives for symmetry: 400 feet to deep center, 375 down the power alleys, 340 to left, 325 to right (to compensate for prevailing winds blowing in from right field). But it will not have a cliff.

To those who love Clark Field and the game that is played there, the new field is a giant antiseptic mistake. College baseball is an imperfect game; that is its beauty and the key to its enjoyment. Place it in a major league setting and it becomes an awkward parody. In the major leagues, a ground ball to the shortstop is an out, but in college ball, even a pop-up carries an element of doubt. The appeal of college baseball is that the players have talent but not perfection. They are capable of astounding accomplishment and unbelievable mistakes; they are, in short, just like ourselves. It is a game all of us can understand.

The major league game is different. It is beyond our ability to play. We can appreciate it as an art form, but as a sport it can be unbearably dull and predictable. Even the gap between the best player and the worst appears minuscule until it is viewed over the whole season.

Baseball is a marvelously conceived sport, and the college game takes advantage of its best aspects. Baseball is the only team sport played without a clock; no lead is ever completely safe and no game utterly lost. Relief pitching specialists have all but obliterated the late inning rally in the major leagues, but skills aren’t so specialized on the college level. Last year the pivotal game of the College World Series saw Minnesota’s all-American pitcher holding a one-hit, fifteen-strikeout, seven run lead over Southern California in the ninth inning only to lose 8-7. Nothing like that has happened in the professional World Series since 1929.

Baseball also isolates its participants better than any other sport. It is impossible to assess the individual performances of football players without sophisticated motion picture equipment, but baseball strips the contestants of their anonymity, putting their skills on display on both offense and defense for all to see. College baseball adds the element of intimacy: because the ball parks are smaller than major league stadiums and spectators sit much closer to the playing field, the onlooker is part of the game to an extent not possible at a major league park. You can spot the third baseman’s fatal mistake as he takes his eye off the ball, and you know before he does that the ball is past him. You can watch Burt Hooten in complete control, baffling opposing batters with an unusual pitch called a knuckle curve, but you’re close enough to know that the dreaded pitch is not a strike, and that major league hitters wouldn’t be swinging at pitches that college hitters are missing by a foot. And if you watch closely, you may begin to understand what a wide range of skills the game of baseball demands of those who would play it, and how difficult and subtle this game really is.

This is what college baseball is all about: relaxing in the awakening spring, watching a great sport being played by real people. Somehow the cliff seems an appropriate, even necessary part of the scene. It tells us, more eloquently than his 600 foot home run did, that Lou Gehrig was out of place here. It is something that could never be part of a professional stadium, something that reminds us that even at a school which has won the championship 48 times in 58 years, what is going on is only a game.

- More About:

- Sports

- Texas Longhorns

- NCAA

- Austin