My bloodline runs along Highway 59 in East Texas. In the towns and hamlets that sprout off the interstate, I can trace my ancestors on both sides of my family, going back to slavery. Unlike millions of African Americans who fled the South during the worst of the Jim Crow years and Klan terror, my people set down roots and dared anyone to run us off. As my late great-aunt Altha said, “We were Texans, period.” And we met the challenges of living in difficult times for black folks with a commitment to public service and the fight to make this state better for all Texans. My latest novel, Bluebird, Bluebird (Mulholland Books, September 12), is the first in a series of books that will be set along Highway 59. It’s a thriller and a character study, but it’s also, at heart, a love letter to black Texans and a thank you to the ones who raised me. Here’s an atlas of my family’s history along Highway 59.

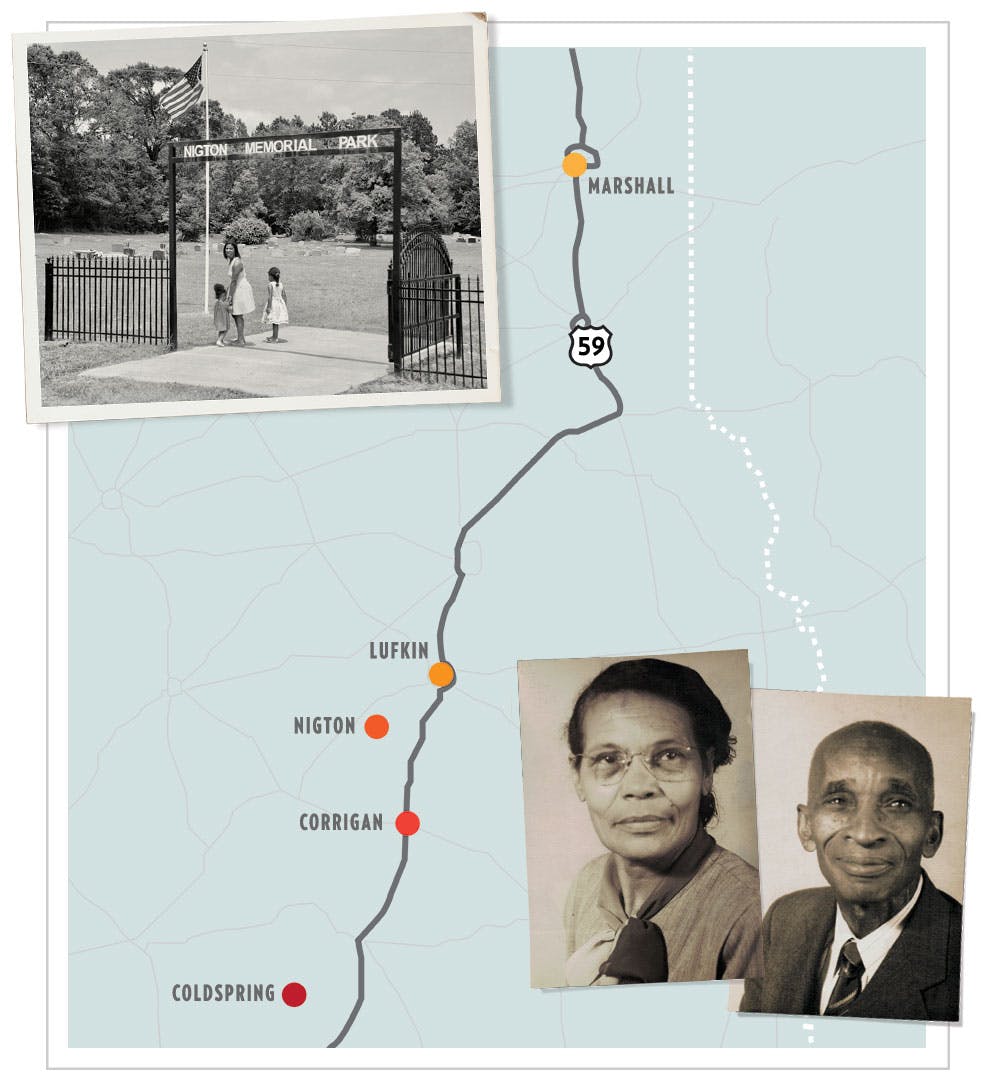

After Emancipation, my maternal ancestors helped settle the freedmen’s colony of Nigton, which reportedly got its name from white locals tagging the community “Niggertown.” Two decades ago, when the state tried to change the name, my second cousin Pam went to Austin to lobby against the change at the request of her brother Wayne Johnson III, an assistant state attorney general. We refused to let our history be erased.

Off of Highway 59 sit ten acres in Coldspring that have been owned by my father’s mother’s side of the family for more than a century. By farming cotton and corn, my great-grandparents Willie and Edna Perry put six kids through college and graduate school. Five of them became educators, including Ervin Perry, who was the first black professor at the University of Texas at Austin. (UT’s Perry-Casteñeda Library is in part named after him.) Ervin and his twin brother, Mervin, were the inspiration for William and Clayton, the twin brothers in Bluebird, Bluebird.

My mother’s paternal grandparents, Elsie and Wayne Wright Johnson (right), settled in Corrigan. W. W., as he was known, was a poet who founded a colored school. He and Elsie raised eight kids, most of whom became educators. My mother’s maternal grandmother, Fannie Sweats, had a clapboard cafe in town where she served homemade food—she was known for her tea cakes—for colored travelers. This was the inspiration for the Geneva Sweet Sweets cafe in Bluebird, Bluebird.

My mother, Sherra Aguirre, was mostly raised in Lufkin, where her parents were teachers. Her father was a founding member of the local Negro Chamber of Commerce.

My dad, Gene Locke, was mostly raised in Marshall, where his mother, Jean Birmingham, was an educator who opened one of the first black businesses—a department store—in the downtown area. In 1975, her husband, Sam, was elected to the city commission and then, five years later, mayor—a striking development in a town where the White Citizens Party had once prevailed and lynchings were not uncommon.