I’m sputtering down Interstate 10 in a ’92 Mazda, en route from Los Angeles to my parents’ house in Corpus Christi. Today is the Tucson–El Paso leg. At some point, I veer off the highway onto an isolated farm road curving along the Mexican border and wind up in a desert choked with cactus and brush. The air conditioner has perished, so it is hot as blazes. I roll down the windows and contemplate my thirtieth birthday, which is a month away. My twenties were consumed by my first book, a memoir about traveling around the Communist bloc. During the decade it took to research, write, and publish it, I grew keenly aware that I was living backward, more in my past than in my present. It is time to move on, but where? To what?

When asked this on my book tour, I had a ready reply: Learn Spanish. Despite being third-generation Mexican American (on my mother’s side) and growing up 150 miles from the Texas-Mexico border, my Spanish is best described as Tarzan Lite: a primitive vocabulary spoken entirely in present tense. My mom faced so much ridicule for her accent growing up, she never taught my sister or me how to speak Spanish properly. I mostly picked up curse words in school (¡pendejo!) and opted to learn Russian in college. Studies show that only 17 percent of third-generation Mexican Americans can speak Spanish fluently, but it riddles me with guilt—especially now that I’ve entered the publishing world. I’m turning down invitations to speak to groups I supposedly represent because I literally can’t communicate with them.

A logical life plan would be to venture across this desert and explore the land and tongue of my ancestors. Yet the very notion terrifies me. Ask any South Texan. To us, Mexico means kidnappings and shoot-outs in broad daylight in Nuevo Laredo. The unsolved murders of young women in Juárez. It means narco-traffickers in every cantina and explosive diarrhea from every comedor. When I was in high school, a college student got snatched off the street while partying in Matamoros during spring break. Bound and gagged, he was driven to a ranch run by a satanic cult. Next thing you know, he was menudo. One worshipper wore a belt made of his victims’ spinal cords.

So go to Mexico? Thanks, but I’d rather return to Moscow and track down my old mafioso boyfriend.

I’m cresting a small hill now. Glistening pools of water appear on the road up ahead, then evaporate. It is dizzyingly hot. I glance at the gas gauge. It’s nearly empty. Cell phone: roaming. Not a soul has passed me on this road. If the Mazda breaks down, I’m toast. Better turn around and rejoin the highway. My foot hovers above the brake as I grasp the clutch.

Something appears in the distance. Objects in the middle of the road. Moving sluggishly, then quickly. Bears? What kind of bear prowls around the Arizona desert? No. They must be wild dogs, big ones, standing on their hind legs and . . . running?

No. They are people. Mexicans fleeing the border. I slam the brakes and blare the horn.

“¡Agua! ¡Tengo agua!” I scream out the window.

They must need water. I have two bottles. I must give one to them.

But . . . what if water isn’t all they need? What if they ask me to take them somewhere? Of course I will say yes. How can I deny a ride to people in the middle of the desert?

But what if they don’t just want a lift? What if they want my car?

Or what if they take it? Toss me into the cactus and roar away? That is what I would do, if the tables were turned: Throw out the gringa and go.

The irony here is immediate. Nearly every accolade I have received in life—from minority-based scholarships to book contracts—has been at least partly due to the genetic link I share with the people charging through the snake-infested brush. What separates us is a twist of geographical fate that birthed me on one side of the border and them on the other. They are “too Mexican.” I am just enough.

The Mazda has slowed to a crawl, but the border crossers have vanished. Water shimmers where they stood. I pause a moment, wondering what to do, then slowly begin to accelerate. As I look off into the desert hills from which they descended, a surprising thought flashes through my mind: I want to go to Mexico.

By the time I’ve dropped off the car in Texas and flown home to Brooklyn, where I’ve lived for three years, I’ve regained my senses. I can’t go to Mexico. That would entail quitting my day job, cramming everything I own into storage, and ravaging my savings account. It’s just too easy—and I’ve done it too many times before. It’s why I’m nearly thirty and still sleeping (alone) on a futon in a cramped apartment with multiple roommates while my friends have wandered off, bought houses, and procreated. Besides. What if I did learn Spanish—and nothing changed? For years, this has been my pipe dream: If only I spoke Spanish, I would be more Mexican. But what if it isn’t possible to become a member of an ethnic or cultural group—to will yourself into it, to choose? What if you can only be born and raised into it?

That would rule me out. I made a conscious choice to be white, like my dad, one day in elementary school. Our reading class had too many students, our teacher announced, and needed to be split in two. One by one, she started sending the bulk of the Mexican kids to one side of the room and the white kids to the other. When she got to me, she peered over the rims of her glasses. “What are you, Stephanie? Hispanic or white?”

I had no answer to this. Both? Neither? Either? My mother’s roots dwelled beneath the pueblos of northern Mexico; my father’s were buried in the Kansas prairie. I inherited her olive skin and caterpillar eyebrows and his indigo eyes.

But in South Texas, you are either one or the other. Searching the classroom for an answer, I noticed my best friend, Melida, standing over by the brown kids. “I’m Hispanic,” I announced. The teacher nodded, and I joined the Mexicans. A few minutes later, a new teacher arrived and led us to another room, where she passed around a primer and asked us to read aloud. That’s when I realized the difference between the other students and me. Most of them spoke Spanish at home, so they stumbled over the strange English words, pronouncing “yes” like “jess” and “chair” like “share.” When my turn came to read, I sat up straight and said each word loud and clear. The teacher watched me curiously. After class ended, I told her that I wanted to be “where the smart kids are.” She agreed, and I joined the white class the following day.

For the next eight years, whenever anyone asked what color I was, I said white. It was clearly the way to be: Everyone on TV was white, the characters in my Highlights magazine were white, the singers on Casey Kasem’s American Top 40 were white (or black). White people even populated my books: There were runaways who slept in imperial chambers at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Sweet Valley High twins who roared around California in convertibles, girls named Deenie who rubbed their Special Places with a washcloth until they got a Special Feeling. (I sat in the bathtub for hours, trying to find this Special Place. Was it that spot behind my elbow? Or just beneath my toe?)

True, I often wondered when their primos would burst onto the scene in their lowriders. And how come nobody ever ate barbacoa or cracked piñatas or shopped for empanadas at H-E-B? But I took no offense at these absences. White people’s stories just seemed worthier of being told. And so I grew closer to Grandma in Kansas because she resembled the feisty Jewish grandmothers in my books more than Abuelita, who lived on a ranch thirty miles out of town. I used to beg Grandma for stories about life on the prairie as she baked me vats of macaroni and cheese. She regaled me with the adventures of my great-great-uncle Jake, a hobo who saw America with his legs dangling over the edge of a freight train. When I wound up across the kitchen counter from Abuelita hand-rolling tortillas, however, I’d sit in silence—and not just because of the language barrier. I simply couldn’t fathom that she had anything interesting to say. I’d watch her flip the masa on the burner and wish she’d whip up something like Are-You-There-God-It’s-Me-Margaret’s grandma would. Like matzo ball soup. I’d never tried this dish before, but it sounded like mini-meatballs floating in cheese sauce.

I switched back to being Mexican my senior year of high school. I was thumbing through the college scholarship bin in the career center when my guidance counselor called me into her office and asked a familiar question: “What are you, Stephanie? Hispanic or white?”

Before I could respond, she offered that my SAT scores weren’t high enough for funding if I was considered white. If I was Hispanic, she predicted, doors would swing open. “Think about it,” she said.

I did for about three seconds, then changed the little W on my transcript to a big fat H. Suddenly, I qualified for dozens of additional scholarships. I applied for them all, and acceptance letters poured in. Not only was my freshman year at the University of Texas at Austin fully funded, but I received free tutoring, a faculty adviser, and a student mentor, plus invitations to myriad clubs and mixers. It was quite exciting—until I started meeting the other Latino scholarship recipients. Some were the children of migrant workers. A few had spent summers picking grapefruit themselves. Their skin was brown, and they had endured hardships because of it. I quickly realized that I had reaped the benefits of being a minority but none of the drawbacks. Guilt overwhelmed me. Should I give back the money I’d received? Transfer to a cheaper school? Or try to become that H emblazoned across my transcripts?

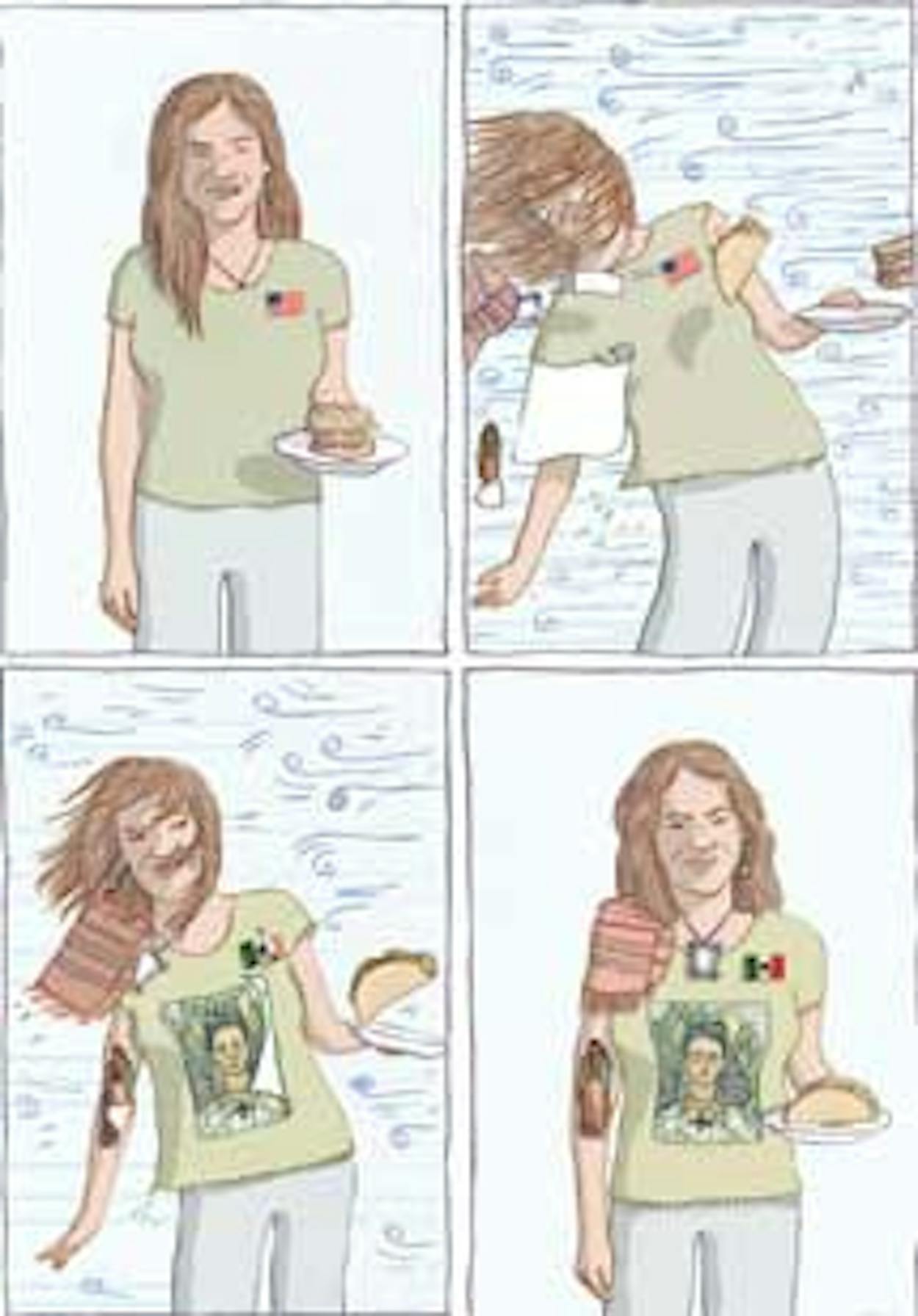

Mexifying myself was fun at first. I decorated my room with images of Frida Kahlo and the Virgen de Guadalupe. I taught English to Mexican kids and drank lots of margaritas. I changed my white-bread middle name (Ann) to my mother’s maiden name (Elizondo) and made everyone use it. I even got a Colombian boyfriend (bad idea).

Then a Chicano politics class inspired me to work as a minority recruiter at the office of admissions. Half of our student staff was Mexican; the other half black. I became the volunteer coordinator, which meant I cajoled scores of students out of bed on Saturday mornings to help us call promising minority high school seniors and lure them to our school. We then sent buses to fetch them to Austin, where our volunteers showed them around campus and played host for the night. The afternoon of the first arrival, our boss called me to the podium to pair up the “mentors” with the “mentees.” Not only did I butcher some of the black students’ names, but I couldn’t remotely pronounce Echeverría or Guillermoprieto. The auditorium was soon in a mild uproar. “Who you think you are, Miss?” someone shouted.

For a biracial, nothing is more humiliating than this: trying to be half of yourself while the other half keeps intervening—and getting caught. I tried to crack a joke about it. “A bad Mexican,” I replied. But my voice trembled.

Just then, my colleague Rosa tapped my shoulder. I had an urgent phone call, she whispered. After excusing myself to the audience, I hurried off the stage as Rosa resumed the matching. There was, of course, no phone call. Rosa had simply tried to save some dignity—our organization’s, and what remained of my own.

That was more than a decade ago. I’ve since made several attempts to learn Spanish, enrolling in classes and stockpiling workbooks. But I dread using it. My Spanish sounds like a failure to me, as though everything I manage to say is an admission of what more I cannot. What will Mexicans say when they hear it: “¿Tu mamá es mexicana? ¿Híjole, what happened to you?”

I decide to move to Mexico, to find out.