This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

Chalk it up, if you will, to the failed visions of an old newspaper wretch, but local TV news turns my stomach. Anchors named Skip and Cindi-with-an-i reading scripted ad-libs from a TelePrompTer, weather forecasters in earmuffs throwing snowballs at the camera, self-appointed protectors of the downtrodden feigning rage because some capitalist has charged an elderly indigent $1800 for a used TV set. It really saps me when one of these charlatans turns to the camera and brays, “For Action News, this is the Terrible Swift Sword!” I recognize that TV news has considerably more to do with show business than with journalism, but the thousands of elderly indigents who pay $1800 for used TV sets (and whose loyalties support the ratings) do not. They believe they are witnessing something of substance, and that’s what makes me want to beat my typewriter into a barf bucket—that and the knowledge that these counterfeits are making more in a week than the ink-stained journalists of my generation made in six months.

I keep thinking of a vintage Bugs Bunny cartoon with Bugs lost in the desert and close to starvation. He spots a carrot, but when he gets closer it turns out to be only a picture of a carrot. It’s Bugs Bunny journalism that causes my intestinal insurgency. A flash here, a snippet there, a dance to the side, a pause, a serious set to the mouth, a basso profundo bromide: “We’ll have the scores a little later. And speaking of scores—scores of people were killed in Beirut when . . .”

I heard the following exchange right here in River City:

Anchor: “In our lead story, a Travis County grand jury is expected to indict an Austin man suspected of the savage murder of his wife. And Gordon is here with the weather.”

Weatherman: “Her name wouldn’t be Alicia by any chance? I say that because we’re tracking a tropical storm . . .”

This sort of exchange used to be called happy talk. That pejorative isn’t used much anymore, but it still rings in the industry’s ears. The theory behind happy talk is that it makes bad news go down better. What it really does is to make any kind of news sound so empty and contrived that even death by flamethrower seems like comic relief. It wouldn’t be so bad, except that the stations keep hyping the myth that anchors are journalists. You’ve probably seen commercials showing one of these clowns tearing a page out of a typewriter as though it were something more urgent than a letter to Max Factor. The truth is, anchors often don’t write what they read. Writing is not a requirement for the job, and in some cases reading doesn’t appear to be. Reporting is generally beyond their comprehension. If you happen to catch an anchor broadcasting from the actual scene of a story, doing what is called a stand-upper (thus proving that anchors have legs), in all likelihood a producer and a writer arrived hours earlier and spoon-fed every query and observation to the dolt in front of the camera. There is no law that an anchor has to be a journalist any more than there is that an actor has to be a playwright, but there are laws against fraud, and TV flaunts them daily.

Bugs Bunny journalism is irresponsible not merely because it neglects what’s below the surface of a story; it also distorts our perception of events at a time when we need all the perception we can muster. I’m not talking about the juxtaposition of horror and silliness—news of death squads followed by news of yacht races. I’m talking about the juxtaposition of programming—any kind of news preceded by Fantasy Island. Television is not a medium that encourages, much less requires, sequential thought. The kind of mindlessness that TV writers create is designed to send audiences into the commercial willing to rank ring around the collar just below leprosy in the natural order. God knows how many viewers come to believe that soap opera characters are real people or that Robert Young is a doctor or that Jerry Lewis is a humanitarian or that Gavin MacLeod is an actor. Walter Cronkite used to worry that the day might come when a majority of the people depended entirely on television for their understanding of events. Sad to say, Walter, that’s the way it is. Fantasy has blended into reality until it is nearly impossible to separate the two; if we ever do get invaded by Martians, my advice is to stay away from the tube.

In fairness, electronic journalism has come a long way in a short time. Where local TV news existed at all twenty years ago, it was an afterthought, a sop to the FCC, which was always jumping on the industry to produce “public service” programming. WBAP/5 in Fort Worth (now KXAS/5), which began in September 1948, was the first television station in the Southwest, and almost from the day it started operation it aired a show called The Texas News. Back in the early fifties Channel 5 news was staffed by a news director and six or seven reporter-cameramen with primitive equipment. The format resembled the old Movietone newsreels—flickering film of car wrecks and politicians doffing their hats. The station’s three weather forecasters (one, Harold Taft, is still there) worked full time as meteorologists for American Airlines. The show ran from 4 or 5 minutes to a tops of 55 minutes (the day after John Kennedy was assassinated). “The length of the show depended on how much film we had that day,” recalls Russ Thornton, a Channel 5 veteran who is now a station executive.

News was a money-loser in those days. Station executives were convinced that advertisers were not about to spend money on shows that nobody but the FCC watched. The exception was weather. The weather was popular from the beginning, and it was always brought to you by the First National Bank, which wasn’t interested in bringing you the war or the flaming car crash. News shows had to pander to their sponsors to get any support. I recall a matinee-idol sportscaster in Austin in the late sixties who once devoted most of his show to an interview with a local car dealer (a big advertiser, of course) who had just returned from playing in the Bob Hope Desert Classic pro-am. (“I tell ya, Mel, that’s one honey of a golf course!”) The sales department had a big influence on news back then. Stanley Marsh, who owns TV stations in Amarillo, El Paso, and Roswell, New Mexico, told me, “If a car dealer got in a new model, we filmed it as a news event. We [finally] realized that the only way to maintain integrity was to separate sales from news. Once TV news was able to bite the hand that fed it, it became popular.”

In September 1971 something happened that drastically altered television’s approach to news. The prime-time access rule forced most local stations to provide at least one hour of non-network programming in prime time. While a lot of station managers hurried to buy up reruns of Gilligan’s Island, a few put their resources into news. News was relatively cheap to produce, it qualified as public service, and the local stations could keep all the advertising dollars it generated.

To the astonishment of the industry, news turned out to be a terrific money-maker, mainly because it is the only unique programming that most stations offer. By the time cable began blanketing the country in the seventies, news was the single local production that kept a station in business. Now, for example, viewers in Bryan–College Station have more than twenty cable channels, and yet Bryan’s small local station, KBTX/3, commands more than 60 per cent of the local audience during its news time slots.

One barometer of a station’s success is what salesmen call cost per rating points, though nobody except Arbitron and Nielsen, the two major rating services, knows what that means. In the simplest terms, if one per cent of all the televisions in the market tune in to your program, you get one rating point. If the percentage of viewers goes up, your ratings go up. The cost of a rating point—the only thing that really counts—depends partly on the law of supply and demand, but it is mostly determined by how big the market is. The more households a program reaches, the more an advertiser pays for a spot. In the Dallas market rating book published last May, for example, WFAA/8 had a 17 rating for its ten o’clock news—compared with KDFW/4’s 13 rating and KXAS/5’s 12. At the current price of about $250 per rating point, a thirty-second spot on Channel 8’s ten o’clock news would sell for $4250 (17 X $250), while the same spot on Channel 4 would bring in $3250 (13 X $250). When you consider that Channel 8 runs fourteen spots with its ten o’clock news, that $1000-per-spot difference tells you a lot about the cutthroat motivations of the business. Over a year you’re talking about a potential $20 million of revenue for Channel 8’s ten o’clock news against roughly $12 million for Channel 4’s.

Local news has always taken its cues from the networks. About twenty years ago CBS decided to expand its fifteen-minute evening news. The occasion was Walter Cronkite’s interview with President Kennedy. Instantly—everything in TV happens instantly—a format was born and Cronkite became the quintessential anchor. In less than a month NBC went to half an hour of news with Huntley and Brinkley. CBS and NBC affiliates, most of whom had produced their own fifteen-minute news to fill up the half hour, went to thirty minutes, and in some cases to a full hour.

A longtime joke in the industry, ABC news didn’t go to thirty minutes until the late sixties. A decade later, ABC led the pack—in innovations, if not in ratings. Many thought ABC had gone daffy when it named Roone Arledge to head the news department; his background was sports. But he understood how technology could redefine news coverage in a style the print media couldn’t match. Arledge made his case in 1976 and again in 1980, when ABC’s coverage of the winter Olympics shattered viewing records and set standards for both substance and popularity.

“Instead of using one camera to film downhill skiing, he used fourteen,” says Marsh, whose ABC affiliate in Amarillo pulled a record 55 per cent of the viewers in February 1980. During the hostage crisis, Arledge instigated Nightline, and he had the guts to stick with it. In my opinion, Nightline is the greatest coup in the history of electronic journalism. There is not a better journalist in any medium than Ted Koppel, a point that I fear may be lost on those undergraduates who aspire to be Skips and Cindis. Koppel brings skills to his job that aren’t taught in J-school—a sense of history, a perspective, a feeling for the complexities of culture and tradition. There’s a lesson here, or should be. An anchor who looks like Howdy Doody won’t win any beauty contests, and yet Koppel has an indefinable charisma that engages your total attention. Even Cronkite was never able to think on his feet (so to speak) the way Koppel does—night after night after night.

The bad news is that some ABC affiliates have been dropping Nightline. Their criticism is that although Koppel is okay when there’s a hot story like the Korean Air Lines massacre or the invasion of Grenada, it’s yawntime when he gets caught interviewing opera stars or proponents of pine-tarred baseball bats. Unfortunately some stations have replaced Nightline with such dreck as Barnaby Jones. Who knows? Bugs Bunny reruns may be next.

What makes TV news entertaining is technology—the gizmos called bells and whistles. Some of the bells and whistles, like a digital video effects system that creates whirling images and pictures within pictures and split screens, are mostly cosmic illusion. “advertisers expect it,” explains one TV executive. “They see a commercial on cable done with a digital effects system and they want their drugstore commercial to look that way.”

But electronic news-gathering equipment and computerized production equipment are tools of the trade; they make it possible for television to cover some stories far better than newspapers or magazines can. The medium is capable of truly Dickensian moments, as when one of the networks interviewed a young woman who said things were so bad in Ohio that she was forced to beg for food. Then the camera cut away to a smirking Secretary of Agriculture, who said that if his family could live for a week on food stamps, anyone could.

Even the smallest local stations can no longer afford to be without modern equipment. A tape machine costs the same in the richest market in the state as it does in the poorest, but the little stations have got to come across or get out of the game. Instead of the old hand-held Bell & Howell windups, television crews today are armed with Minicams, portable recorders, live vans, superspeed editing machines, computerized consoles, digital video storage systems, even helicopters. Five minutes after a story breaks, they can have it in your living room.

The new technology has enabled even the poorest and most inept stations to pick and choose from a variety of material supplied by daily network feeds, the Cable News Network, microwaves, satellite uplinks and downlinks (whatever they are), and a lot of other gadgets and services that were unheard of a few years ago. Syndicated-news companies such as Telepictures and Group W also produce an abundance of material that stations can edit so it looks homegrown. The ABC stations in Dallas, Houston, and San Antonio have their own mini-network through which stories are traded, and CBS stations in Texas and four other states are about to announce a similar plan for sharing stories.

A lot of stations, however, particularly those playing catch-up, do not understand the difference between solid journalism and gimmicks. In recent years the tendency among upwardly mobile station managers has been to “go Magid.” The term pays tribute to Frank Magid, one of the best-known “news” consultants in the country. Magid was among the first to apply marketing concepts to TV news. Now consultants are paid to advise clients on everything from background music to hard news judgments. The name “Magid” is anathema to most serious journalists, some of whom use it generically to mean that which is trivial or cosmetic. But Magid has never pretended to have all the answers. “I have nothing against Magid,” a WFAA veteran told me. “He’s just trying to make a buck. The problem is the station executives who take him as gospel rather than just seasoning.”

Some consultants are nothing more than talent headhunters who specialize in finding on-camera people for client stations. They tape newscasts from the top 100 to 150 markets and maintain detailed files on salaries, on which contracts are about to expire, and on who is looking to move where. Using test groups of viewers, consultants have been known to evaluate faces and presentations according to such quasi-scientific processes as Q ratings (which are nothing more than opinion polls), galvanic skin response tests, and brain-wave measurements. Some consultants counsel clients on wardrobe, makeup, hairstyle, even personal habits. One advised Quin Mathews, reporter-anchor at KDFW/4 in Dallas, to lose weight and become active in community affairs.

All the big talent agencies, like William Morris in Beverly Hills, have jumped into the local TV news market, signing clients as quickly as they can be located. Agents feed tips to headhunters, who pass them along to client stations. Anchors have become commodities, just like cotton futures and hog bellies. The day may come when they are traded openly on the floor of the stock exchange. TV critic Marvin Kitman writes in the Washington Journalism Review that he expects someday to turn on his television and hear: “Gold was up in Zurich and in trading of anchormen, the price was up in Boston and down in Dayton and Fort Lauderdale.”

Willis Duff, senior partner of audience Research & Development in Dallas, gets very defensive when anyone questions the journalistic abilities of anchors or even suggests that anchors be journalists at all. “Anchors make journalism work,” Duff told me. “If there is a single trait you look for in an anchor, it’s the ability to be engaging.” And what makes an anchor engaging? There are many answers, but the simplest one is ratings. As you can see, it’s a vicious circle.

The number of people trying to get into this racket is staggering: come spring, 16,000 journalism graduates will be competing for 3000 jobs across the country. Dr. Al Anderson of the University of Texas journalism department estimates that 100 of UT’s 700 journalism majors are concentrating on broadcasting. Watergate, which transformed journalists from deadbeats into folk heroes, is partly responsible, but I fear that the main attraction is the prodigious six- and seven-figure salaries that lightweights like Tom Brokaw are reportedly earning.

Not every student dreams of getting rich, much less of breaking another Watergate, but they all get dewy-eyed when Anderson tells the story of the marginally attractive, slightly overweight girl who sat just where they’re sitting. She may not have had a date for the homecoming dance, but she had something much more important. She had star quality. Two years out of UT’s journalism school she was making $100,000. Some got it, some don’t.

Anderson estimates that maybe 50 per cent of the students planning a career in TV news will have the fortitude to stick it out, which probably means living (and maybe dying) in a place like Lubbock or Port Arthur, where the starting salary is about $250 a week. Three or four may make it as far as Dallas, where a good, experienced reporter can earn $40,000 a year or more. One or two may make it to the networks, but try telling those who didn’t that it’s a glamour profession.

Though it galls me to acknowledge this, a single “personality” can send a station from bottom to top. KOSA/7 in Odessa-Midland leads its market with a whopping 60 per cent largely because of a smarmy TV personality named J. Gordon Lunn, who does the weather, exhibits drawings by third graders, and occasionally hosts adoring fans on station-sponsored trips to Hawaii. “Women actually scream when they see him in person,” says Betsy Triplett, a former Channel 7 staffer who later became news director of KTPX/9 in Odessa-Midland. A news director in the Rio Grande Valley told me that almost every station in the country is looking for an attractive and intelligent black woman, no doubt because of the success of Iola Johnson at Channel 8 in Dallas.

Local stations tend to have a pack mentality: if a gimmick works in one market, it is bound to be stolen by a station in another. Every market has at least one station that offers medical advice—chalk this up to the popularity of Dr. Red Duke. Most markets have a “Wednesday’s Child” (please, somebody, adopt him/her) or, in smaller markets where there are few adoptable children, fuzzy spin-off shows such as “Little Orphan Animal.” Consumer reports, troubleshooting, legal and financial advice, movie and restaurant reviews: there is a headlong trend toward these soft, short features. Tom Eastland, the news director of KXIX/19 in Victoria, told me: “Nobody gives a rat’s ass that we do a good job covering city hall. But we get all kinds of response when we send a girl to the shelter every Thursday to play with the kitties.”

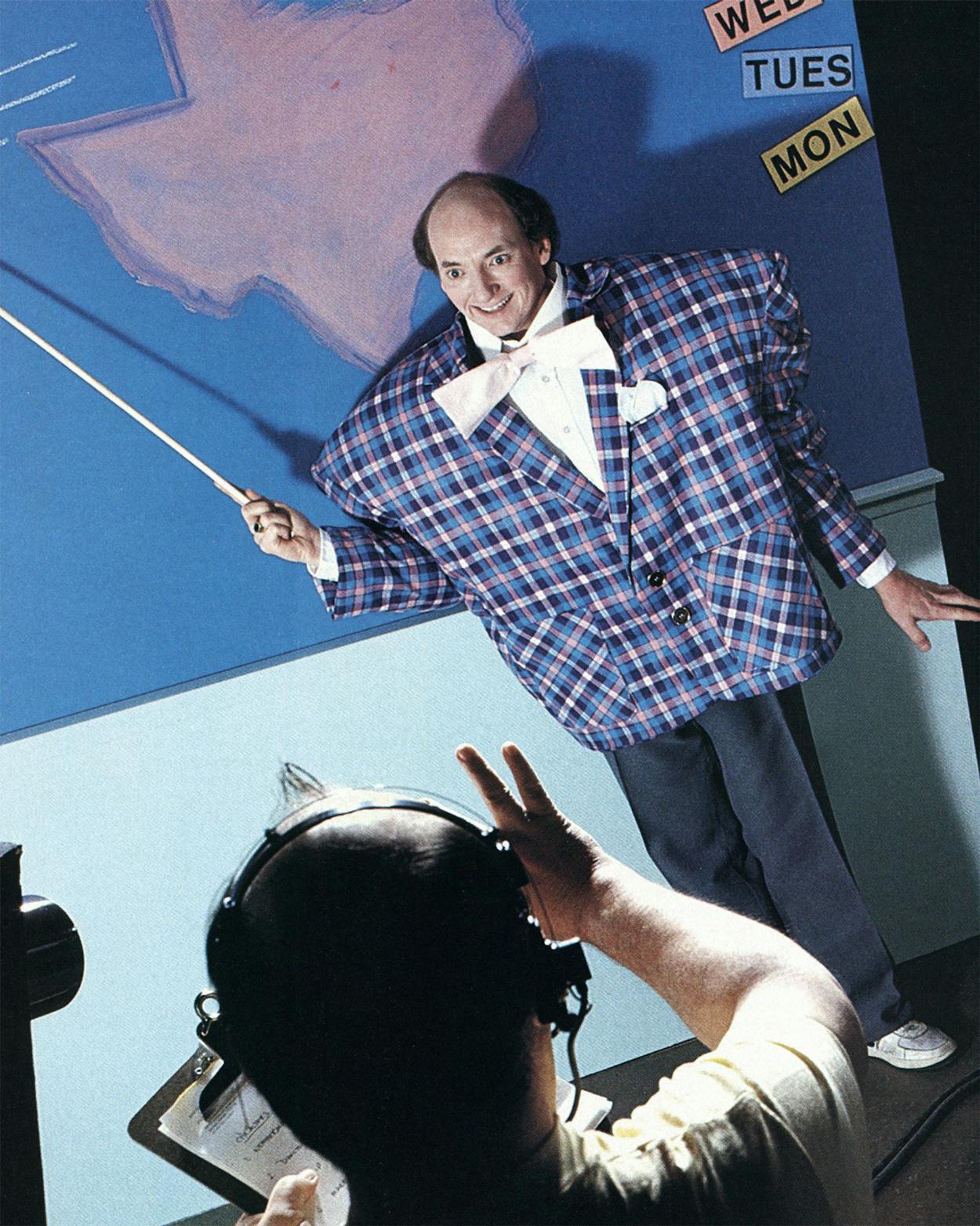

At times this submission to the pack mentality can be downright stupefying. The damage done by such chuckleheads as Tom Snyder, now an anchor at WABC in New York, and Warner Wolf, the sports loony at WCBS in New York, is incalculable in its effect on local markets. Wolf, whose pompous, staccato drivel inspired part of Joe Piscopo’s comedy routine on Saturday Night Live, was hired from a station in Washington, D.C., to help anchor ABC’s winter Olympics, and he bombed spectacularly; industry insiders love to recount how he required 37 takes to complete one forty-second spot. Like a lot of other no-talents, both Wolf and Snyder have an uncanny ability to succeed by failing. WCBS now pays Wolf close to $500,000 to be obnoxious. These days you can find a Warner Wolf clone in most major markets—Scott Murray at KXAS/5 in Fort Worth and Dan Patrick at KHOU/11 in Houston are modified examples. Joe Fowler of KSAT/12 in San Antonio is closer to the real thing, and Vic Jacobs of KTVV/36 in Austin is beyond satire. Jacobs is one of those bonzos who wear Napoleon hats and throw rubber bricks at the camera. Nothing terribly original about that. But here’s a guy who allows his wacko style to obscure his subject completely. “He probably knows as much about sports as any of the other sportscasters in town,” says an official in the University of Texas athletic department, damning with faint praise. “But he doesn’t go out of his way to show it.” Jacobs understands that in Austin it is best to bleed burnt orange, and he has become a raving “homer.” His preview of the Texas-Arkansas football game was a tour of a meat locker, where he pretended to ripsaw hanging carcasses of hogs (hogs—get it?), closing with a tight shot of him eating raw meat.

Worse than the chronic sports hack is the imbecile weather forecaster—weather is too important to be turned over to idiots. My main bitch about weather reporters has nothing to do with accuracy, though my old granny could predict the weather more accurately with a bucket of chicken entrails. The thing is, hardly any of them have any feel for weather. They all come from northern Minnesota or some place like that. A typical midsummer forecast goes: “Well, Cindi, what can I say, it’s going to be an absolutely gorgeous and perfect weekend here in the ol’ Capital City.” Translation: We expect a high of 110, with 88 per cent humidity. The weekend weatherman on Austin’s Channel 36, Gordon Smith, reminds viewers to attend the church of their choice and wastes a part of his allotted time with a canned feature called “This Day in History” (he sometimes gets the day wrong), which concludes with Gordon’s platitudes to celebrities who are having birthdays that day. “Eddie Fisher and Jimmy Dean, both great, great singers, are fifty-five years young today.” Back in August Gordon announced that Princess Anne of Great Britain was 73. He meant 33, but what the hell, no weatherman is perfect.

It galls me, too, to confess that it doesn’t take a whole lot of talent to be a successful journalist. Television is not an industry that allows quality to interfere with making a buck, and the most important requirement for local TV newscasters seems to be an ability to follow the herd. The boom in local television news will continue and no doubt intensify as the state grows, but the quality of the news is something else. While you are waiting around for it to improve, you’d better hold on to your library card.

- More About:

- TM Classics

- Television

- Longreads