On a frosty morning on November 26, 1986, a fishing guide named Mark Stevenson took two anglers out on Lake Fork, in East Texas. By the late afternoon, he had found a prime location on the north side of the lake at the intersection of two creeks. One of his clients spotted some commotion under a nearby bush and pitched his jig. The fish bit, but the angler couldn’t hook it. He tried two more times. No luck. Then Stevenson made an attempt, and whammo!

He yanked on his pole and quickly brought the fish to the side of the boat, where his client hauled up the gigantic bass with a net. “That’s a new lake record,” Stevenson said. But when he finally got the fish into a local tackle shop called Val’s, where he could weigh it, he discovered that at seventeen pounds ten ounces, he had beaten more than the lake record—he had beaten the state record. He named her Ethel. (Though one report stated that Stevenson’s inspiration was a member of his family, he claims that he was referring to Ethel Mertz.) Then he slipped her into Val’s minnow tank and headed back out on the lake.

When he returned for Ethel that night, the parking lot at Val’s was packed with people who had heard that a live state-record bass was inside. Admirers were taking Ethel out of the tank for photo ops. Reporters surrounded Stevenson, asking him questions. Stevenson estimates at least a hundred spectators turned out to see his big bass that night. Word had even spread to Bill Rutledge, then the director of fish hatcheries for the Texas Parks and Wildlife Department.

The timing was propitious. For several years, Rutledge had been trying to solve a vexing problem: Whenever an angler landed a really big bass, a vital specimen was being removed from the genetic pool. The State of Texas was spending a good deal of time and money trying to breed larger and larger bass and thereby improve its reputation as a fisherman’s paradise. To achieve these goals, Rutledge needed more of the big fish left in the water to spawn. But how could he convince anglers to throw back the giant fish they had just caught? He’d have to revise the philosophy of bass fishing, which, at that point, was oriented more to the frying pan than the scale.

Rutledge was not the first to dream of building a bigger bass. A hundred years ago, only one type of largemouth bass resided in Texas waters. Known to most as northern bass—and to some as Micropterus salmoides salmoides—it topped out around five pounds, which seemed plenty big to most anglers, until the seventies, when Bob Kemp came along. Kemp, then the regional director of fisheries for the TPWD, knew that Florida’s native bass reached ten pounds or more. Bass that size were extremely rare in Texas; the state record of 13.5 pounds had stood unchallenged since 1943. Kemp decided to take matters into his own hands. In 1971 he personally paid to have two insulated boxes of Florida fingerlings in oxygenated bags flown in as brood fish. The shipment totaled several hundred tiny fish. In the following twelve years, the state record was broken six times.

Rutledge proposed something even more radical. What if anglers were asked to turn over to the TPWD any bass over thirteen pounds in return for a free fiberglass replica? The live lunker would be taken to the hatcheries, where she would spawn with males from Florida stock, and the resulting fingerlings would be released into Texas waters (females tend to be much larger than their male counterparts, who rarely top five pounds). Since bass that are thirteen pounds or more have the genetic potential to get even bigger, Rutledge surmised that this breeding strategy might allow them to grow big fish while avoiding an impossibly large number of shipments of Florida bass fingerlings.

Nonetheless, when he introduced his big idea at a staff meeting in the fall of 1986, he was met with skepticism. “I thought it was the craziest idea that ever lived,” says David Campbell, who was the manager of the Tyler State Fish Hatchery at the time (it closed in 1997). Campbell suspected he would be asked to do the heavy lifting on the project since his office was close to Lake Fork, a prime bass location. Campbell is a thin, long-limbed gentleman in his sixties, with dimples, sand-colored hair, and a brushy white mustache. He speaks with the melodious inflection and earnestness of Andy Griffith. “I told Bill, ‘Nobody’s going to catch the biggest bass of his life and turn around and give it to you,’ ” he recalled. Some staffers thought the thirteen-pound mark set the bar too high. Others, like Campbell, weren’t sure if there was sufficient interest in big bass to validate the time and enormous effort the program would require.

But Rutledge would not be dissuaded. The way he saw it, his plan was in the best interest of the fishermen, even if it involved prying prize fish out of their hands. He thought that the promise of even bigger fish would stir something primal in fishermen and help persuade them to invest in the plan. Think Moby Dick. Or the giant squid. The bonus to the state was obvious: A successful campaign could add visibility to the department’s underfunded, decades-old hatcheries and help build Texas’s aquatic facilities into some of the best in the country. Rutledge acquired sponsors—the Lone Star Brewing Company, Jungle Labs, and Cajun Boats—to pay for publicity materials and fiberglass replicas of the trophy fish. The program, called Operation Share a Lone Star Lunker, was scheduled to begin in December.

Because of Ethel’s arrival, it began earlier. After hearing reports of the giant lunker, Rutledge hunted down Campbell and ordered him to pick up the fish. When Campbell arrived at Val’s, he stood in the crowded parking lot, net in hand, completely dumbfounded. He eventually loaded Ethel into his truck, with Stevenson’s blessing, which was not as hard to get as he’d thought it would be. It wasn’t until he was in the truck on his way back to the hatchery in Tyler that, he said, “the significance of what we were trying to do began to sink in.”

The weeks that followed proved that the interest in the fish wasn’t fleeting. “The hatchery became a three-ring circus,” Campbell recalls. “We had parking places for maybe ten cars, and folks wanting to see the fish would line up down the road, causing traffic problems. We had more than ten thousand people come that year and sign the Tyler hatchery’s registry book.”

After Ethel was featured in major newspapers and national nightly news broadcasts, Operation Share a Lone Star Lunker went into full swing in every reservoir in the state. It was a quick success. Within the first five years, almost a hundred bass were entered into the program. The Legislature, noticing the attention, set aside $8 million for the TPWD hatcheries. In time, quiet, rural areas became populated with new motels and restaurants to accommodate the tourists jamming up the boat ramps. Tales spread of Japanese newlyweds in the U.S. who visited two places: Disneyland, in California, and Lake Fork. One East Texas couple awed by big bass got married in front of a display for bass lunkers at the Sam Rayburn Reservoir. When Ethel finally died, on August 25, 1994, at the age of nineteen, about 1,500 people attended her funeral. By then, no one doubted the power of big bass to capture the public imagination.

One day last spring, I paid a visit to the Texas Freshwater Fisheries Center, in Athens, an emporium of sorts that doles out two to three million bass offspring each year to Texas lakes. Inside a supermarket-size warehouse lined with rows of fiberglass fish tanks from one end to the other, David Campbell stood wearing the TPWD uniform, a khaki button-down shirt and khaki slacks. These days, true to his prediction, he has become the face of the program, now called Budweiser ShareLunker. It is Campbell’s cell phone number listed on thousands of wallet cards telling people to call 24 hours a day if they catch a bass that weighs more than thirteen pounds. But his initial misgivings have disappeared. “Yes, I get tired,” he said. “But really, truly, if you see me out there, I’m just tickled to death.”

To date, more than four hundred ShareLunkers have been submitted to the program. Campbell has collected almost every one—no small feat when you consider that each must be brought to the center within twelve hours of its capture. “I’ve done intake of the fish in my sleep two, three times, I believe,” he said. “You wonder when you go home: Did I really do that?”

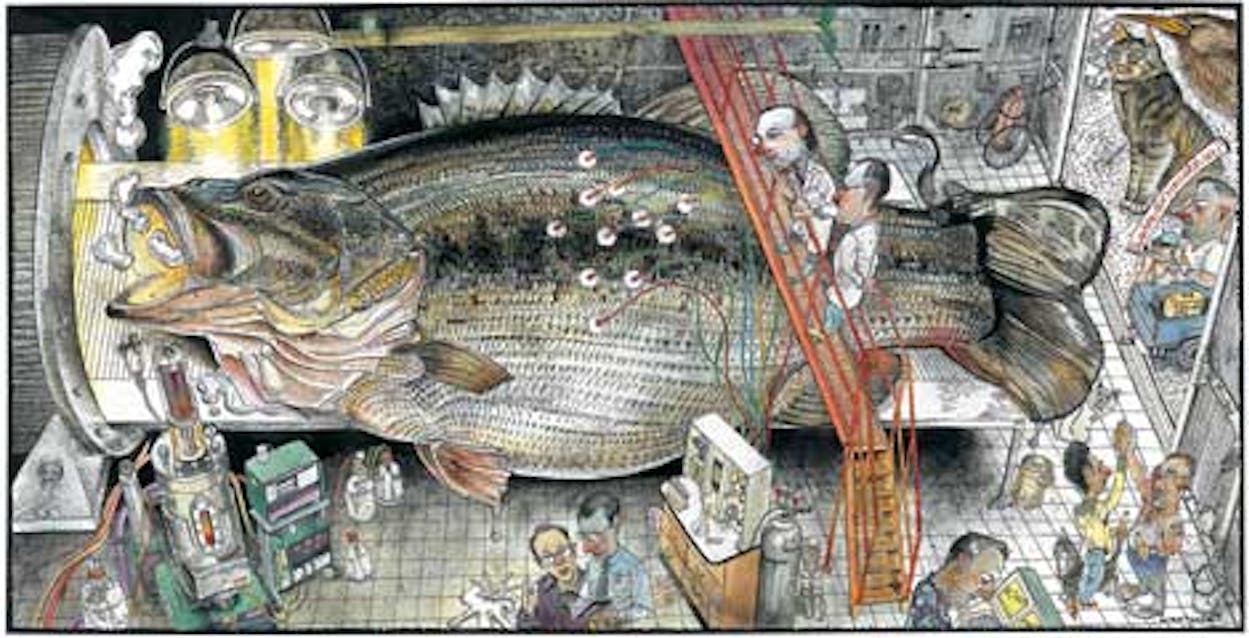

The routine is simple. Returning from the retrieval of a new lunker, Campbell climbs into the back of his white pickup truck, pulls on a pair of blue rubber gloves, and plunges his hands into a two-hundred-gallon tank affixed to the truck bed. He feels around for the fish, then slips her into a black bag and moves it with one gliding motion into a cooler before the fish has the notion to get away. Then he rolls the cooler into the “Lunker Bunker,” also known to Campbell as the ICU, a fluorescent-lit room that contains twenty circular tanks for ShareLunkers. Here, Campbell and the biologists on hand can nurse any problems the fish may have. Opening the cooler, he reaches in with a tape measure and determines girth, then he stretches the fish flat on her side and assesses length. Afterward, he moves the fish to another tank and quickly latches the top before it can jump out. As a testament to his deftness, it rarely does.

Campbell had to admit that the initial interest in the ShareLunkers, while positive, made him uneasy. Never mind that some fish came to him with broken lower jaws because they’d been held incorrectly or had fungus growing on their eyes because they had been kept out of the water too long. “I was afraid everybody would say, ‘You killed this fish!’” he said, shaking his head. He has been known to spend hours in the ICU with the lights dimmed, trying to persuade a female to eat a goldfish. Validating his concern, several of the first few lunkers died. Stress, it turned out, is as confounding a problem in bass as it is in humans.

“We can open up a fish and name everything inside, but we can’t tell you why certain things happen,” he said. “There is more we need to know.” Since launching the program, he has been able to refine his methods so that many more ShareLunkers live and spawn.

The day I visited, I watched a male in the courting process. A female ShareLunker as heavy as a Thanksgiving turkey had been taken from the ICU and placed in one of the 15,360-gallon troughs in the warehouse garage. The breeding couple were placed in their own compartment of the trough, separated from each other by a small, black T-shaped net some staffers refer to as a “spawndo” (like a “condo”) that gives the female brief moments of respite from what would otherwise be relentless harassment. The male lingered above a plastic mat that simulated a nest. His goal was singular: Coax his assigned partner to the mat. If she dropped 8,000 to 40,000 of her tiny gold eggs, he could fertilize them and the resulting fingerlings would be released, eventually, into the wild. Oblivious to the circumstances that had provided him with an opening, the male began his flirtation. Slowly, he drifted away from his side of the tank. He rolled onto his back and glided under the lunker like a limbo contestant, attempting to nudge her to his fake nest. The lunker’s reaction couldn’t have been colder—she merely twitched her left eye. He returned—pretty quickly—to his mat, but a few moments later, he approached her again. You had to admire the tenacity.

This male, of course, was not the first to be smitten by a large female bass. The screen saver on Campbell’s office computer runs an automatic slide show depicting anglers with their ShareLunkers, just hours after capture. The fishermen appeared to have witnessed the type of miracle that causes ecstatic tremors and fainting spells.

“I’ve seen adults so excited they couldn’t tell me how to find them,” Campbell said. “I’ve had them on the phone trying to tell me, and the wife is like, ‘No, Jim, you take a left.’”

Anglers are always happy to see him. How many have dreamed of Campbell’s approaching with a net, like the Publishers Clearinghouse Prize Patrol with a giant check? No one has ever refused to turn over a fish, and Campbell sees in this enthusiasm a way to reverse a larger cultural trend. In February 2008 the National Academy of Sciences released a report titled “Evidence for a Fundamental and Persuasive Shift Away from Nature-Based Recreation.” The paper noted that since the eighties, involvement in outdoor recreation has declined 18 percent nationally. Texas is doing better than other states in this regard, but how long can we defy the odds? As more people across the nation watch bass fishing on TV, fewer actually get in their boats and do it.

“When I was a child growing up, fishing was one of those events my family did together,” Campbell said. “Now, unfortunately, many adults are busy. If we can get them interested in the outdoors, they’ll realize the outdoors is not free.” He leaned in. “So okay, I’m reaching out here for the lunker. But what I really want is bigger than that.”

About 2.5 million anglers fish Texas lakes and rivers each year. According to the TPWD, spending by outdoor enthusiasts has a greater economic impact than the state’s cotton, dairy, poultry, and corn industries combined. Taken together, Dell Computer, Lockheed Martin, Electronic Data Systems, and Dow Chemical provide fewer than half the jobs that in-state nature recreation does. According to a 2006 U.S. Fish and Wildlife survey, Texans spend more on fishing—some $3.36 billion—than on any other outdoor activity. And of all the money they shell out on fishing, they shell out the most on bass.

Though fishing brings to mind images of nature undisturbed, Texas’s current frenzied love affair with the largemouth would not exist without human meddling. Long before Rutledge and Kemp, human intervention had begun to alter the piscatory landscape. In the late 1800’s, for example, northern fingerlings were brought to Texas from Illinois, Missouri, and Virginia.

More drastic than any physical relocation of fingerlings was a massive effort, throughout the twentieth century, to dam the state’s rivers for hydroelectric power. This transformation began in earnest in the thirties, as part of Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal. Though its primary purpose was rural electrification, the indirect benefits to the state’s fish supply were huge. Prior to this, in the early 1900’s, Texas had about 191,000 miles of rivers but only one lake, the swampy Lake Caddo, in the state’s northeastern corner. While flowing water was an ideal habitat for the northern bass, if Texas was ever going to support the Florida subspecies, it would need static water systems—lakes. Roosevelt’s plan gave us just that.

The state had not seen a topographical overhaul as radical as this since the Ice Age. After the drought of the fifties, impoundment levels increased and continued well into the seventies, resulting in about eight hundred public reservoirs—a total of 1.7 million acres that had once been dry land. The impact of these reservoirs on the state’s economic and demographic outlook was dramatic; the effect on its fishermen was profound. Modernizing the state’s infrastructure gave people more leisure time, and many of them spent their extra hours on the new lakes. Entrepreneurs recognized a lucrative business in rods, reels, bait, boats, and motors and began to market their products more aggressively. Interest in bass fishing rose slowly and steadily.

The changes transformed what was once a simple pastime. Today, skills are honed, methods studied, equipment fetishized, and professionals idolized. Fishing is now a sport, and, like running, it has become increasingly sophisticated. Rare is the hungry angler who just sits on the shore, plunks down a lure, and hopes for the best. The introduction of the ShareLunker program dovetailed with a national trend in bass tournaments, opening a whole world of tackle, sponsorship, television programs, and advertising. Most bass fishermen invest time and a hunk of change in boats. If they live in Texas, there’s also a good chance they participate in bass tournaments, since Texas currently hosts about five thousand such events. Though it is difficult to measure this number against other states’, most of the experts I asked agreed that Texas now probably has the most bass events in the country.

Breeding alone will not create the Platonic ideal of a fish—or at least Texas’s gigantic version of the ideal. Scientists from all over the state are needed. Within the first few days of a ShareLunker’s arrival at the Athens fishery center, biologists in the Lunker Bunker investigate the new creature with the curiosity of archaeologists exploring a past civilization. They take blood from its gills to test stress levels, they cut a piece of the fin for DNA testing, and they insert a passive integrated transponder tag behind one of the fish’s pelvic fins so that after release the bass can be scanned and identified with a wand like those used at a store checkout. (If the likelihood of a fish’s repeatedly finding itself in the Lunker Bunker sounds unlikely, it isn’t. Several unlucky fish have ended up riding in the bed of David Campbell’s pickup twice, and one fish from Lake Alan Henry, south of Lubbock, was caught three years in a row.)

A few weeks after I watched lunker intake at Campbell’s lab, I followed a fin sample that had been clipped from a ShareLunker. Its destination was a test tube in the hands of a 29-year-old geneticist named Dijar Lutz-Carrillo at the A.E. Wood Fish Hatchery, in San Marcos. To prepare me for our meeting, Lutz-Carrillo had e-mailed two relevant papers he had written, “Admixture Analysis of Florida Largemouth Bass and Northern Largemouth Bass Using Microsatellite Loci” and “Isolation and Characterization of Microsatellite Loci for Florida Largemouth Bass, Micropterus salmoides floridanus, and Other Micropterids.” When I arrived at his laboratory, he was examining samples taken from descendants of Cuban bass that had been smuggled into a private pond back in the seventies. Dressed in a T-shirt and jeans, he seemed like a mellow hipster who could talk as easily about micropterids as indie bands. He asked if I’d received his research papers. I replied that I had. He smiled and winced. “Did they help?”

Lutz-Carrillo’s job supports the entire Inland Fisheries Division of the TPWD, but within the ShareLunker program his marching orders originate from a project called Operation World Record. OWR was launched in 2001. Its single intention is to selectively breed a fish in Texas bigger than the 22-pound 4-ounce bass caught in Montgomery Lake, in Georgia, in 1932. At the same time, through genetic monitoring, it aims to prevent inbreeding, which could result in deleterious recessive traits in the fish population. “They want to know,” he said, “Has this particular fish been caught as a ShareLunker before? Or is this fish an offspring of a previous ShareLunker?”

The process begins strangely, with a fin segment the size of a chad placed in a test tube. Lutz-Carrillo eliminates everything but the DNA via a multistep process involving submerging the fin segment in various solutions, heating it, cooling it, and spinning it in a centrifuge that pulls on the test tube sample with 13,400 times the force of gravity. Fully prepared, the sample looks like plain water, with no visible sign of the fin. Lutz-Carrillo pours the liquid from the test tube into a gene sequencer that uses an electric current to draw the DNA through a porous gel matrix with convoluted tunnels that lead to the bottom of the machine, where a laser registers the time it takes for each strand to complete the journey. The longer the DNA strand, the slower it is. From the strand-size numbers registered by the laser, Lutz-Carrillo gathers all kinds of information.

“If you’re a Florida largemouth bass, you’ll have a strand that’s x long,” he explained. “A northern is y long. A hybrid would have some x along with some y.” Through complicated calculations, he can identify the fish’s parents and pinpoint just how far back in Kemp’s experiment the family lineage was introduced to Texas.

With this information, Lutz-Carrillo can tailor the breeding program to produce the biggest, healthiest bass possible and, hopefully, the biggest, healthiest bass ever. But if you talk to enough fishermen, you’ll get the feeling that this world-record fish may already be out there, swimming in Texas waters, loitering under every boat and teasing anglers. Stories of “the big one that got away” frequently reach Campbell. His typical response is to smile and nod and say, “Yeah? I’ll believe it when I weigh it.” In recent years, two fish weighing about twenty pounds each floated up on the shores of Lake Fork. (One is rumored to have had scars indicating a close encounter with a hook.) But the true leviathan, the bass that breaks the world record, inevitably, consistently gets away, leaving anglers to their fishing tales.

Kelly Jordan, a former Lake Fork guide who is now a professional fisherman, is a true believer in the probability of a world record in Texas. Jordan is a good-looking guy in his thirties, with yellow hair and perfectly straight white teeth. Like most professional anglers, his face is sunburned a deep shade of red except for the area covered by his sunglasses. “I was night fishing in August,” he told me. “I think the year was ’94. I set the hook and the fish didn’t even move. A bell went off in my head like, ‘Oh, my God.’ It was a huge fish. This fish broke my rod, locked up my reel, and broke my line—all in about five seconds. No, maybe not even five seconds. Three seconds. People said, ‘Oh, you hooked a big catfish.’ Well, I’ve caught a lot of big catfish. Catfish don’t do what that fish did. So I said, ‘Well, it was either the world record or it was the only blue marlin in Lake Fork.’” He sighed. “I had nightmares about that fish,” he said. “It sounds weird, but a lot of people who had similar experiences say, ‘If I could just know how big that fish was, I’d feel better.’ That’s how I felt.”

The fruits of the ShareLunker program were on display this spring at the second annual Toyota Texas Bass Classic, a tournament held on Lake Fork from April 18 to April 20. There are other great bass lakes in Texas: the Amistad Reservoir, for example, or the International Falcon Reservoir. But more than half of the bass submitted into the ShareLunker program come from Lake Fork. The current state record—18.18 pounds, caught in 1992—came from Lake Fork.

Because Lake Fork bass are protected by the most restrictive limits in Texas, the Classic differs from the state’s other bass tournaments, where anglers go fishing solo and return for a weigh-in with fish in tow. At the Classic, anglers are set up in teams of four, with a pair going out onto the water in the morning and a pair going out in the afternoon. The team that comes back with the most combined pounds of bass wins, and the members split $250,000, with lesser amounts paid to the other top slots.

This year, in order to abide by the lake’s restrictive catch-and-release rules, each boat was assigned a judge who would ride along and weigh every fish on the spot before it was released. Only one fish longer than 24 inches would be hauled to the stage per team for weigh-in. This setup was an experiment in the amount of secondhand, two-dimensional drama a crowd would tolerate. The multitudes onshore would watch most of the activity via television crews that followed the anglers in camera boats, and the results would be broadcast on the JumboTron, with the highlights airing on CBS later in the spring.

On the first day of the tournament, at about 6:45 in the morning, the nearly full moon had disappeared and the sun was beginning to rise. Just offshore, the idling boats sported advertisements for sponsors like GrandeBass, Strike King, Megabass, and Yamaha. One boat publicized Eyes on Jesus Ministries, with a drawing of a pair of yellow eyes stretched about five feet across the side of the boat, staring disconcertingly over the water. The anglers were NASCAR-ized from neck to waist in patches touting various bass companies. Most of the top pros were present. Kevin VanDam, of Michigan, considered the best bass fisherman in the world, hands down. Terry Scroggins, of Florida, whose team won the inaugural Toyota Texas Bass Classic, in 2007. Alton Jones, of Waco, fresh from his win at the 2008 Bassmaster Classic—the Super Bowl of the sport. Takahiro Omori, who moved to Lake Fork from Tokyo in the nineties and won the 2004 Bassmaster Classic. The early crowd consisted mostly of press and families of the pros. After listening to a young local karaoke devotee sing the National Anthem, the pros gunned their boats over the water with enough velocity to push the tears from their squinting, watery eyes back toward their temples.

By mid-morning, the anglers on the water were standing in their boats, casting. Bass tend to swim up near shore and spawn in the spring. Experienced anglers will look for where the birds are feeding, how fast the wind is blowing, what kind of front is coming in, and adjust their baits and depths accordingly. Though these subtle displays of fishing prowess were difficult to perceive from the live JumboTron feed, Gary Klein, a veteran pro, told me that anyone who couldn’t appreciate a pro’s level of expertise—anyone, for instance, who might venture that the whole spectacle was about as exciting as watching a stranger do laundry—clearly didn’t understand a thing about fishing.

“Hunting and fishing are sports,” he said. “All these others—basketball and football—are games. What other sport lasts ten hours a day for three to five days? We don’t step into an arena and two to three hours later it’s over. I’m trying to catch something I can’t even see.”

As if to tempt onlookers with the promise of giant fish lurking just out of sight, the Classic had erected displays of previous monsters. I wandered over to a tent that exhibited replicas of bass that had held the state record over the years. Eternally posed with their shellacked bodies curved to simulate motion, their mouths were open wide enough to fit the head of a little boy who pointed and gasped at each. A local had caught a twelve-pound bass in the nearby cove and dropped it in a semitruck-size aquarium display tank used for lure demonstrations. Invariably, throughout the rest of the weekend, people kept pulling out their camera phones and snapping pictures of the twelve-pounder. On the stage, an announcer hyped “B-b-b-big bass!” while the speakers blared “Who Let the Dogs Out?” The crowd, wearing T-shirts that said things like “Born to fish, forced to work” and “Kiss my grits,” whooped and stood on their feet as the JumboTron showed close-ups of fish amplified many times their actual size.

On Saturday afternoon, David Campbell stopped by to check the lunker activity. He huddled with about a dozen TPWD staffers under a tent. Because of water temperatures and weather changes, the fish were not near the shore, as everyone had hoped. They were scattered in water anywhere from one foot to thirty feet deep. No one was catching anything over eleven pounds twelve ounces. Disappointed, a TPWD staffer said, “Bless the water, Dave.”

“If it worked that way,” he replied, “I’d have the world record by now.”

By Sunday, Kelly Jordan, the former Lake Fork guide, and his team had won the Classic with a total of 228 pounds of fish. But Campbell would miss Jordan’s victory speech. At eight thirty that morning, he had gotten a call from an angler at the International Falcon Reservoir, about 545 miles away, and hit the road to pick up the most recent acquisition to the ShareLunker program: a 14.25-pounder. He arrived back in Athens at one a.m. the following day. After rolling the new entry into the ICU and taking its measurements, he placed it in a tank. “This is number 454,” he said, marking up his paperwork. That it was eight pounds short of the world record didn’t seem to bother him in the least. It was still a big fish.