If the west begins in Fort Worth, the South begins in East Texas, in the rich bottomlands along the Colorado, Brazos, Navasota, and Trinity rivers, where cotton has been king, it seems, forever. The blues came from cotton — from the work songs and hollers that tens of thousands of slaves sang in the fields and from the hymns they sang in church. (Slaves made up almost one third of the Texas population in 1860.) And while Mississippi gets most of the credit for creating the blues, with native sons like Robert Johnson, Muddy Waters, and B. B. King, Texas is where some of the earliest blues pioneers lived and played — including the man who would become Johnson’s teacher, though the two never met.

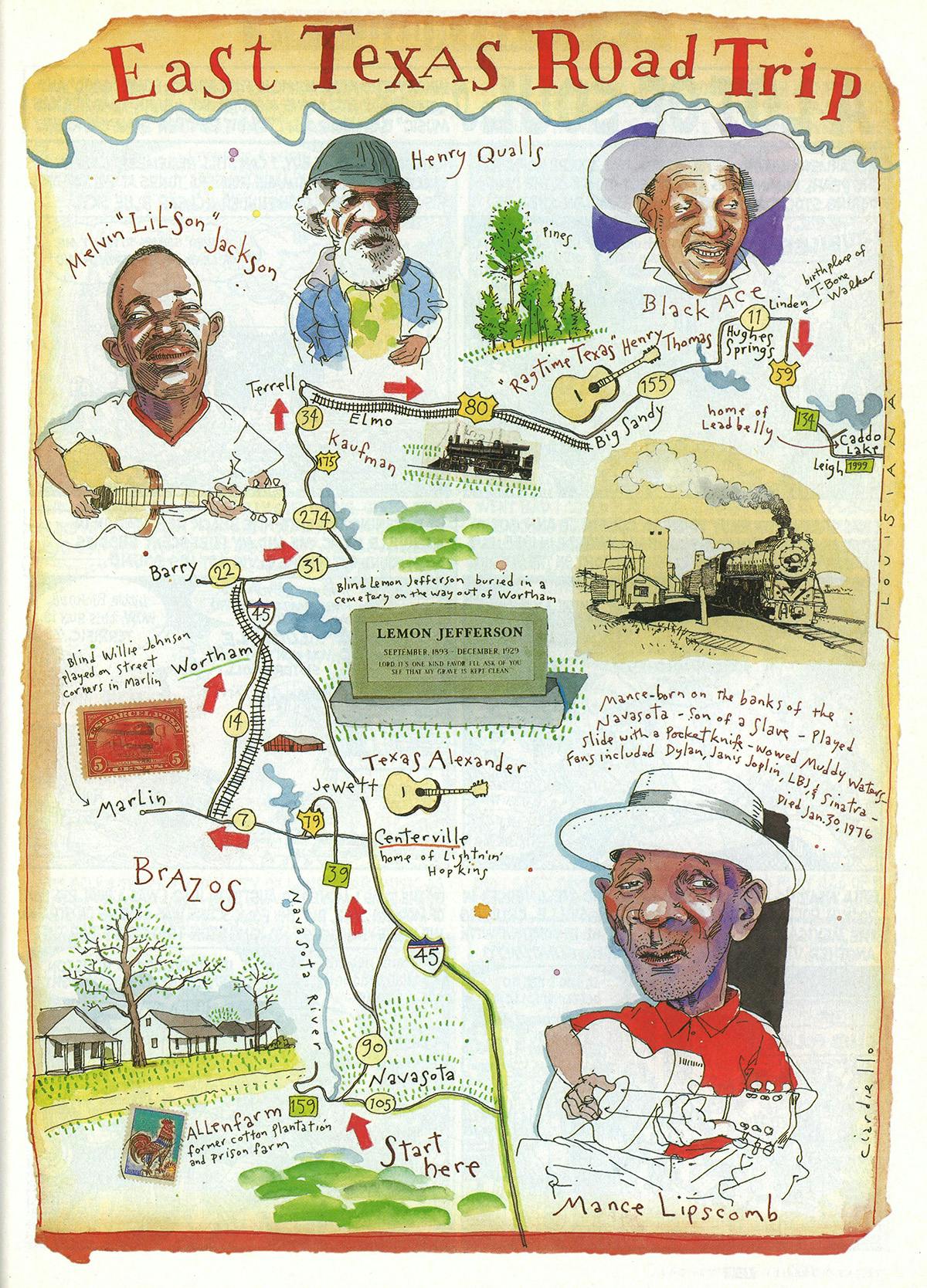

To see where the blues came from, take a weekend, get in your car, and cruise the back roads of East Texas to the birthplaces and haunts of ten Texas guitarists and singers who changed the world. By and large, these ten weren’t just bluesmen; musicians in rural East Texas had to be versatile. They had to play to the whims of black and white folks on the streets of towns like Navasota and Wortham, and they had to keep the dancers happy at Saturday night “suppers” that went on into Sunday morning. They called themselves songsters or musicianers, and they sang and played spirituals, vaudeville tunes, work songs, prison songs, English ballads, local sagas, children’s songs, and eventually, the blues. Most were born into unimaginable hardship and degradation. Two were blind, two were named Lemon, two spent time in jail for murder. One is still alive and playing. They are all linked — by style, blood, or friendship, but mostly by place. These were men of the land, farmers and sons of farmers, and the songs they sang were their versions of the songs they grew up hearing and playing. They changed the words to fit their lives, and they made something new.

To find one birthplace of the blues, start near the birthplace of Texas, Washington-on-the-Brazos, about seventy miles northwest of Houston. Here, just outside Navasota, amid the long, gently sloping hills and meadows along Texas Highway 105, Mance Lipscomb was born on April 9, 1895 — like Texas, on the banks of a river, the Navasota. The son of a slave, he was named Bodyglin Lipscomb but later chose the nickname Mance, short for “Emancipation.” He was a farmer most of his life, usually a sharecropper, giving as much as half of every crop to his landlord. Lipscomb started playing the guitar as a small boy and developed a rolling fingerpicking style for the Saturday-night suppers and dances where he had to be a one-man band, playing rhythm and melody as well as singing. He played slide with a pocketknife — which wowed Muddy Waters when he saw Lipscomb play — and sang folk ballads, pop songs, spirituals, and blues in a gentle voice that he had never heard recorded until he was “discovered” in 1960 by blues fan Chris Strachwitz and folklorist Mack McCormick. Strachwitz recorded Lipscomb in the singer’s kitchen and put out the album as the first release of his new label, Arhoolie. That led to a show in front of thousands at the Berkeley Folk Festival (the first time Lipscomb ever left Texas) and a second career sharing stages with the likes of Pete Seeger, Doc Watson, and the Grateful Dead. Fans included Bob Dylan, Janis Joplin, LBJ, and Frank Sinatra — who once arranged for Lipscomb to entertain him, his girlfriend Mia Farrow, and friends on his yacht in the Pacific for two days.

From Navasota, take 105 four miles west, then go north on FM 159. You’re driving through the vast fields of Allenfarm, a former 20,000-acre cotton plantation and prison farm. Lipscomb farmed around here most of his life; one of the area landlords was the infamous Tom Moore, whom Lipscomb and Lightnin’ Hopkins sang about in the scathing “Tom Moore Blues” (“Tom Moore whup you, he’ll dare you not to tell”). For years Lipscomb refused to play the song publicly out of fear that Moore would have him killed. About eight miles down the road, right before you get to the railroad tracks, make a left at the sign for Allen Farm Road; you will come across old white houses — some inhabited, others abandoned — and farm buildings, several with the name Tom J. Moore printed in large letters.

Head back into downtown Navasota on 105; at the blinking red light, take a left on FM 1227 and go two blocks to Rest Haven cemetery, where Lipscomb and his wife of 62 years, Elnora, are buried about thirty feet in on the right (he died of heart failure on January 30, 1976, and she followed him two years later). After leaving the cemetery, continue through Navasota on 105 until it becomes Texas Highway 90; stay on 90 for twenty miles to Singleton, and then just outside of town turn north on FM 39. Stay on 39 for about forty miles to Robbins, where you turn east onto Texas Highway 7 for eight miles to Centerville, the birthplace of the mercurial Lightnin’ Hopkins. Like many towns in East Texas, Centerville is a faded crossroads; indeed, the town’s western boundary is the thrumming Interstate 45 (Centerville is halfway between Houston and Dallas, though it got its name from its location in Leon County). Sam Hopkins was born here on March 15, 1912, and started playing the guitar young. In nearby Buffalo the eight-year-old screwed up the courage to climb onstage with his guitar and play along with the famous, imposing blues singer Blind Lemon Jefferson at a church picnic. On hearing the racket, Jefferson yelled, “Boy, you got to play it right!” Eventually Hopkins did, playing at picnics and parties while he farmed cotton during the day. In his mid-thirties he moved to Houston, earning his nickname after he hooked up with pianist Thunder Smith; soon he was recording for any label that would offer him money. Hopkins became notorious for not recording until he was given hard cash up front. His blues sounded nothing like his hero Jefferson’s. Hopkins sang in a harsh, untempered voice that could be lonesome one minute and troublesome the next, and his music was a mayhem of mojo, spontaneity, and jolting rhythm as he picked out chaotic riffs, usually making up the words as he went along. He was free-associating on his life, with great humor and bitterness. His repertoire was wide but not deep: As Lipscomb once said, you might think he knew five thousand songs but “He’s singing two songs!” Hopkins was rediscovered in the late fifties by historian Sam Charters and soon was playing with folkies like Seeger at Carnegie Hall and rockers like Jefferson Airplane at festivals. He was a huge star when he died of cancer on January 30, 1982, and more than four thousand fans and friends attended his Houston funeral.

Take Texas Highway 7 west back to Robbins and then FM 39 north for seven miles — past the old slumping barns that look like they’re about to collapse under rotting roofs — to tiny Jewett, home to another of Hopkins’ influences, his cousin Alger “Texas” Alexander (some sources have Alexander coming from Leona, six miles south of Centerville). Born on September 12, 1900, Alexander was a street singer, a cannonball of a man, maybe five feet tall, with a deep, resonant, mournful voice. He began singing at parties and picnics in the area and soon became an itinerant, drifting and sometimes following and singing for migrant cotton pickers. He wound up in New York, where he recorded with jazz and blues greats King Oliver, Eddie Lang, and Lonnie Johnson; he also recorded in San Antonio. He spent time singing with Hopkins in Houston and touring with future blues legends Howlin’ Wolf and Lowell Fulson, and he also spent time in a Paris, Texas, prison in the early forties for killing his wife. Alexander sang in the free rhythm of the work songs he had heard growing up, and it’s amusing to hear the accompanists try to keep up with him on his recordings. They had no choice but to follow the singer — there was no way to compete with that big, thick voice. It served him well on the streets, where he often performed with guitarists J. T. “Funny Papa” Smith or Dennis “Little Hat” Jones. A friend remembered how Alexander would mark the street-corner spot where he was going to sing by sticking a tiepin into the wall. He died of syphilis on April 16, 1954.

From Jewett take U.S. 79 south for 11 miles to Marquez, then head west on 7 for 38 miles to Marlin. One of the larger towns in the area, Marlin is known for its natural mineral waters and the majestic eight-story Falls Hotel, now closed. A colorful downtown mural (“Welcome to Marlin, Tex., Famous for Health”) spotlights local heroes and history but fails to include Blind Willie Johnson, the town’s most famous son, believed to have been born on a nearby cotton farm in 1902 or 1903. Johnson was blinded at age seven when his stepmother, infuriated because his father had beaten her for being with another man, threw lye in the boy’s face — whether she was aiming at Willie or his father is unclear. He had wanted to be a preacher from an early age, but he settled for singing gospel songs (traditional ones as well as his own) on street corners in Marlin, a tin cup tied around the neck of his guitar. Listeners who liked his deep, raspy voice deposited nickels. Johnson may have been a gospel singer but he played like a blues musician, his thumb keeping rhythm on the low strings as he played slide on the higher ones. His haunting slide playing is still studied by modern guitarists; he had an uncanny way of echoing and repeating the vocal hook. He crafted his songs as pop musicians would years later — rhythm, melody, and harmony (many of his recordings feature a female background singer) — and once he had an arrangement down, he rarely strayed from it. Johnson spent much of his time traveling around Central and East Texas, playing at church affairs and on street corners on Saturdays, when farmers and their families would come into town. When he started recording, in 1927, he immediately became one of the biggest sellers in the “race records” genre, outselling popular artists like Bessie Smith. Still, Johnson is known to have recorded only 29 songs (he did one of them twice), and he died of pneumonia in Beaumont in the winter of 1949, after the house that he and his wife, Angeline, lived in burned down.

Retrace Highway 7 east for 15 miles to Kosse, then head north on Texas Highway 14 for 35 miles, the terrain becoming flat and scrubby as you drive parallel to the Southern Pacific railroad tracks all the way to Wortham, the home of the fiercest bluesman of all. Blind Lemon Jefferson was born on September 24, 1893, in Coutchman, a village six miles northeast of Wortham that no longer exists. Some said he was blind from birth, others that he had partial sight. The youngest of seven children, he began playing the guitar at fourteen and soon was taking the train south to play in towns like Groesbeck and Kosse, especially on Saturdays. Sometimes when he played on one street corner in Marlin, Willie Johnson would be playing on another. Jefferson wouldn’t accept less than a nickel and would throw pennies back. He was a songster first, but as he sang his rags, hollers, and hymns on the Texas streets in the teens, he also became one of the first to consistently play the blues (most of his songs have “Blues” in their title), hammering it into the twelve-bar A-A-B verse form we know today. His voice was high and mournful, and he would answer it with guitar riffs; he sang about women, trouble, and a peculiar “black snake moan.”

Jefferson moved to Dallas, got married, became a bootlegger and a wrestler, and spent much of his time in the red-light district. During that time, he traveled with Leadbelly and by himself through the South, following the migrant cotton pickers. In 1925 he began going to Chicago to record for Paramount, and his 78’s became so popular that Paramount created a bright yellow label just for him. Many of his songs — “See That My Grave Is Kept Clean,” “Matchbox Blues,” “Easy Rider Blues” — would become blues and rock standards. But Jefferson also became a poster boy for bad behavior, leaving his wife and country ways behind on his frequent Chicago trips, drinking and whoring and getting paid for his recording sessions with a few dollars and cheap whiskey. He froze to death, drunk, in a Chicago snowstorm after a session in December 1929. Or perhaps he had a heart attack and died where he fell, guitar by his side. Or maybe he was poisoned by a jealous woman. Jefferson was the first true bluesman, famous as much for his short, wild life and mysterious death as for his singing, his playing, and his songs. He became a model for almost every bluesman who came after, from T-Bone Walker (who claimed he used to help lead the blind man around Deep Ellum in Dallas) to Robert Johnson (who learned to play in Mississippi from Son House, who learned to play from a man who was called Lemon because he had learned to play from Jefferson’s 78’s) to every white kid with a guitar over the past forty years who was hungry for the blues experience. It’s not Jefferson’s fault that so many of his apprentices have been so predictable in their interpretations of that experience.

On the way out of town on Highway 14, stop at the weedy, dilapidated “colored” cemetery on your left, across a scrubby field from the clean, symmetrical white cemetery, which sports an American flag at its front gate. In 1930, according to historian Charters, Jefferson was buried in an unmarked grave between his mother and sister toward the front of the cemetery. In 1996 some blues fans from Dallas and Austin raised money for a tombstone memorial to be placed in the cemetery. It sits in the back, however, where some old-timers remembered Jefferson’s being buried. Its inscription: “Lord, it’s one kind favor I’ll ask of you — see that my grave is kept clean.” Two hundred feet away, a highway sign welcomes travelers to Wortham, “Home of the Bulldogs.” No mention is made of the first and perhaps the greatest country blues musician ever.

From Wortham, take 14 north for ten miles to Richland, hop on I-45 north for thirteen miles to Corsicana, and then take Texas Highway 22 west for ten miles to tiny Barry, the childhood home of Melvin “Lil’ Son” Jackson, born on August 17, 1916. Jackson’s father was a farmer who taught him to play the guitar, his mother played guitar in church, and Jackson sang in the choir as a boy. He moved to Dallas to become a mechanic and worked various jobs during the Depression, also singing and playing in church. He was drafted and served in Europe during World War II before returning to Dallas. At some friends’ urging, Jackson sent Gold Star Records a 25-cent amusement-park novelty disc he had made of “Roberta Blues.” The company liked it and put out several of his 78’s; he later recorded for Imperial. Jackson played simple, hypnotic guitar, often repeating stock riffs to keep the lazy beat moving. He sang lazy too, in a warm, resonant voice. In 1956, after a car wreck put him in the hospital, he left music and returned to being a mechanic. Jackson wanted anonymity and didn’t list his name in the phone book, but in 1960 Strachwitz tracked him down and recorded him. The bluesman — always more at home in the garage than onstage — never grabbed for the brass ring again and died of cancer on May 30, 1976, at the V.A. hospital in Dallas.

Double back on 22 through Corsicana and take Texas Highway 31 east for 23 miles to Trinidad. Get on Texas Highway 274 and head north for 24 miles to Kemp, where you’ll hit U.S. 175. Take 175 ten miles west to Kaufman, then Texas Highway 34 thirteen miles north to Terrell, where you’ll head east on U.S. 80 for about six miles to the village of Elmo, the home of one of the last living rural bluesmen. Born on July 8, 1934, on a nearby farm, Henry Qualls learned to play the guitar when he was about fifteen and was soon playing slide like Willie Johnson. By day he worked on people’s lawns; by night he played and sang at parties and picnics. He made his belated recording debut at age sixty with Blues From Elmo, Texas, singing songs by Hopkins, Johnson, Jackson, and himself in a tremulous voice and playing spirited guitar. These days Qualls occasionally plays festivals in Chicago and Europe — and house parties down the road. He lives in an old country home next to the railroad tracks not far from Aunt Kate’s Barbecue on U.S. 80. You can ask for him there. If it’s a Saturday night, you might even catch him at one of those parties, playing his Montgomery Ward Marquis through a torn Super Reverb amp accompanied by his sons. The rest of the world speeds by on 80, oblivious, which is fine with Qualls. “Either they like it or they don’t,” he says. “That’s what I do. It don’t change.”

Continue east on 80 parallel to the railroad tracks. After 26 miles, the land starts to get hilly again around Grand Saline. In Mineola, thirteen miles farther on, the soil gets red and the trees get taller and stand together in the beginning of the Piney Woods. After 23 more miles, stop in Big Sandy, a pretty little town of brick buildings and nice houses that was home to “Ragtime Texas” Henry Thomas. Born in 1874, Thomas left the family farm as a young man and became a hobo, entertaining at dances, suppers, and migrant camps and playing songs on trains for his fare. On “Railroadin’ Some” he calls out the names of stops on various lines, including some on the west-east line — “Leaving Fort Worth, Texas, rolling through Dallas … Grand Saline … Mineola … Little Sandy, Big Sandy, Texarkana” — and then he hoots like a train whistle. He probably started playing the guitar in the early 1890’s, but when the modern world caught up with and first recorded him in 1927 (there are only 23 known songs of his), he was an older man, a jukebox of turn-of-the-century American music. Thomas mixed up-tempo square-dance tunes, rags, vaudeville songs, and a handful of early blues songs (including “Bull Doze Blues,” later covered by Canned Heat and called “Goin’ Up the Country”). Unlike many rural guitar players who came later, Thomas mostly strummed chords, driving the song like an engine and only rarely fingerpicking bass notes or melodies — though he does so on his handful of blues songs, which he may have started playing in the twenties only because blues was becoming a popular genre. He also accompanied himself on the quills, a set of chirping homemade pipes that add to the charisma of his singing, hooting, and guitar playing. Nobody knows exactly how the blues began — there were no tape recorders in the 1890’s — but we can hear the form coming to life in Thomas’ music. If he is any indication, the roots of the blues are in happy music, dance music that was melodic and playful, though that may have just been Henry Thomas. He disappeared at some point — folklorist McCormick thought he might have seen him on the streets of Houston in 1949; others said he was working in the Tyler area in the fifties.

From Big Sandy take Texas Highway 155 north through Gilmer (the birthplace of electric blues great Freddie King), across Lake O’ the Pines, through the forests of loblolly pines on the other side. About five miles past the lake, take FM 161 north for about ten miles to Hughes Springs, home to Babe Karo Lemon “Black Ace” Turner, an unsung hero of the steel guitar. Born on a farm in 1905, he sang in church and played his brother’s guitar; he bought his own at age 22 and began playing dances, sometimes with guitarist Smokey Hogg. He stayed on the farm until 1935, when the Depression forced his family to scatter in search of work. Turner wound up in Shreveport, Louisiana, where he met Oscar “Buddy” Woods, who played a bottleneck slide on a steel guitar he held on his knees. The two teamed up, working at parties in the area. Soon Turner was playing a steel guitar himself, coming up with his own tunings and style. He eventually moved to Fort Worth and cut six songs for Decca; one was “Black Ace Blues.” He played it live on a local radio station, and the deejays began calling him Black Ace. He had a broad, bluesy voice and a unique steel sound — sometimes like a Dobro, sometimes like a moaning slide guitar. After serving in World War II, he picked cotton, mopped floors, and worked in a photo shop in Fort Worth, where Strachwitz found him in 1960. The giver of second chances recorded Ace in his home and released the LP — the artist’s only one — the next year. Ace died of cancer on November 7, 1972.

Go east on Texas Highway 11 for fifteen miles to Linden, the birthplace of urban blues pioneer T-Bone Walker. Take U.S. 59 south for fifteen miles to Jefferson and turn left on Texas Highway 49 downtown. Go just a few blocks, then head southeast on FM 134 for thirteen miles to Caddo Lake’s pine woods and bayous, the home of Leadbelly. The only son of hardworking farmers, he was born Huddie Ledbetter in 1888 just across the state line in Shiloh, Louisiana, a small black community. The Ledbetters moved to the Texas side, near Leigh, when Huddie was five. He grew up picking cotton, driving cows, and playing music on the Cajun accordion (or “windjammer”), guitar, mandolin, and piano. Around the Caddo Lake area, which was more than two thirds black, he heard field hollers, spirituals, English ballads, jigs, reels, vaudeville songs, and string band music. Eventually he was playing them all, and by age fifteen he was entertaining at dances (“sukey jumps”) for 50 cents a night. Ledbetter left home as a teenager and headed west, picking cotton and playing. In Dallas he hooked up with Lemon Jefferson, and the two young musicians spent months traveling, playing, drinking, and carousing. By this time Ledbetter was playing the twelve-string guitar, which would become his signature instrument, banging out bass runs and singing in a booming, confident voice. He had become an entertainer, capable of making up rhymes on the spot, changing songs to fit the audience, and adapting old folk and blues songs. Though Ledbetter could be gentle (he loved playing for children), he was a violent man, and in 1918 he was sent to prison for murder, ending up in Sugar Land; he was pardoned by Governor Pat Neff after singing songs for him when he visited the prison, including “Governor Pat Neff” (“I am your servant, composed this song/Please Governor Neff let me go back home”). Five years later Leadbelly (he probably picked up the nickname in prison) was arrested in Louisiana for attempted murder and sent to the Louisiana State Penitentiary in Angola, where he was discovered by Texas folklorists John and Alan Lomax, who were in search of black rural folk music. They found the mother lode — Leadbelly, a walking encyclopedia, knew more than five hundred songs — and recorded him. After Leadbelly was released in 1934, he went to work for John Lomax, driving him through the South to record songs and even helping by showing convicts how to sing into the machine. He made commercial recordings, moved to New York, and fell in with the leftie folkies of the late thirties, including Woody Guthrie. Leadbelly recorded for various labels and the Library of Congress, doing his versions of “Irene” (later known as “Goodnight Irene,”) “The Midnight Special,” and “Rock Island Line” — songs that would always be identified with him.

Leadbelly died of Lou Gehrig’s disease on December 6, 1949, and was returned to Caddo Lake, to the graveyard of the Shiloh Baptist Church. To get there, take 134 south to Leigh, then FM 1999 east five miles to the Louisiana border. Continue on 1999 for about two miles — the church is on your right. In the mid-seventies the head of the Harrison County Historical Survey Committee said that the remains of Leadbelly, “one of Texas’ truly great musicians,” should be returned to the state where he grew up; Caddo Parish demurred. It wouldn’t be the last time Texans claimed Leadbelly as one of their own.