Show bands, by and large, have always impressed me as stepbrothers in the family of pop music. To them falls the dubious, but necessary, role of filling someone else’s shoes. Obviously pop stars are physically unable to perform their current hits in person at every club and auditorium needing music on Saturday night. Show bands fill that void with the next-best thing—near-perfect (theoretically) renditions of today’s hits. It can be a tedious task, and, except for the pay, show band musicians have little to brag about; to most customers, they are simply human discos, a live dance machine.

It’s not that show bands are always comprised of mediocre talent, but until recently, the values that accompanied such bands didn’t help improve their mechanical image. The typical show band dressed alike, often employing a theme a la Paul Revere and the Raiders; more often than not, they engaged in some form of low choreography, like synchronized kicks and hand jive; they smiled so much that they appeared to be having twice as much fun as the audience; and always in the back of their minds was the thought of making it in Las Vegas someday. Moreover, even if few show bands rose to the magnitude of a Three Dog Night or the Osmonds, the financial rewards even on a local level were sufficient to keep a band complacent, albeit in a creative vacuum.

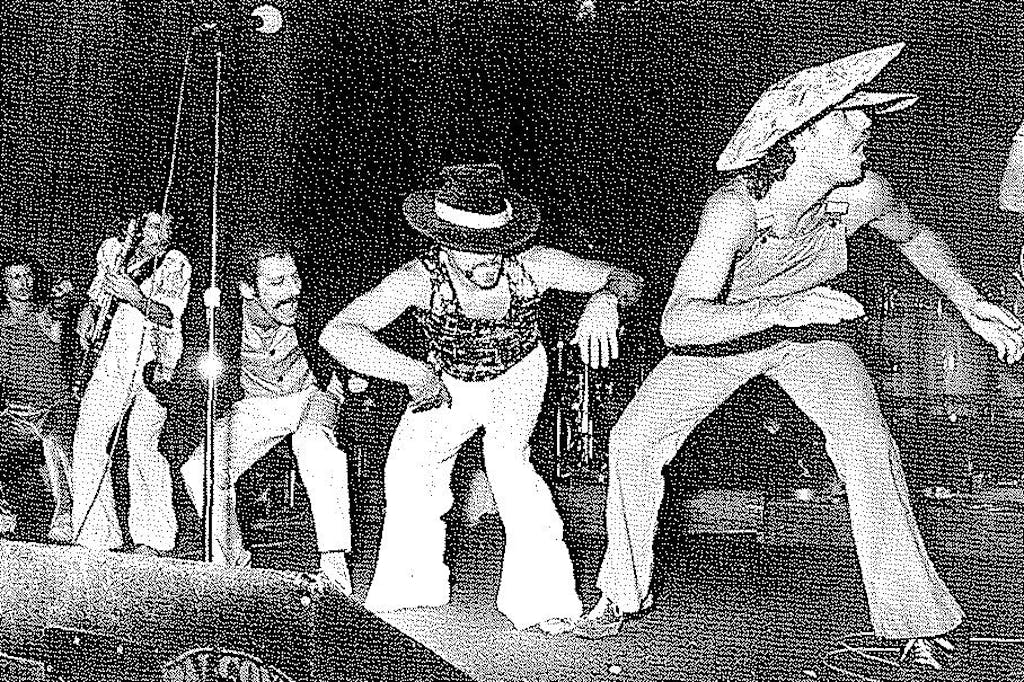

Texas’ best show band, Balcones Fault, covers other people’s hits and aspires to play Vegas someday, too. Each member of the nine-piece band is constantly in motion onstage, though their leg kicks are not too hot. But by no means are they an average white show band.

For instance, the only time I’ve seen them dress alike was one night during the full moon when they opened a concert by punching their way out of plastic garbage bags in slow motion wearing only their underwear. Their versions of other people’s hits aren’t confined to this week’s Top 20; they span forty years of variety entertainment beginning with a Fats Waller medley. Cab Calloway and Ink Spots jive, and traversing to hip-swiveling Latin cumbias, Yankee adaptations of Jamaican reggae, and even some downhome Austin funk like Fletcher Clark’s stirring reading of “Jesus Christ Was a Teenager, Too.’’

There are four (repeat, four) lead singers, one of whom, Jack Jacobs, has an affection for flaunting his flawless Spanish on a heart-wrenching ranchero. Another vocalist, Michael McGeary, like the wrestler Fritz Von Erich, is gifted in the art of baiting. (Example: “Hey you scuzzy scumbags out there. Is anyone listening? Yah, well you know where to stuff it then!” Inevitably the Bronx razz prompts some kind of crowd reaction.) Steve Blodgett invents his own percussion instruments. Saxman Don Elam, with his new bebop burr hairstyle, resembles an escaped convict more than a North Texas State music grad and Houston Pops alumnus. The band assumes many faces, one of the best being their Arabian drag routine under the name of Fez Fuego and the Firebird. They haven’t gotten around to learning “Disco Lady.” But why mess up a good thing when you’ve cajoled the audience into doing a triple bump to “42nd Street”?

Why, indeed? Because Balcones doesn’t want to settle for being the wackiest show band in the Southwest. They’ve got original compositions in their pocket and now an album in the can. They want to be the next Lawrence Welk—“The man has a style down and he’s got an orchestra that’s been with him for years. He’s got singers, dancers, he’s entertaining. He’ll play anything he wants to,” rhapsodizes Clark. They want to be the biggest show band in the world, if they can help it. And they just may be able-to. For no matter how their artistic mettle is gauged, it is impossible not to rank them right up there with ZZ Top and Bill Ham as one of the most savvy bands in Texas. Not so much because leader Jacobs is an ex-political history instructor just shy of earning his PhD, nor because his partner Fletcher Clark is a former vice president of a Boston bank. Collectively, Balcones realizes, as too few other bands in the state do, that it takes more than creative genius to cut the mustard in the music industry today.

In case you’ve been meditating in Nepal or had your radio turned off for the last twenty years, pop music is Big Business. Records and tapes alone generate $2 billion in sales annually. And records are but a portion of a band’s total earning potential. Unfortunately most musicians would rather leave such facts to their managers and pursue their art. But to survive as a national act, a group, show band or otherwise, needs to take care of its own business. A grand design must be formulated, a strategy planned, an image created to unify the performing and recording personae.

Most important, a decision should be reached about how much of a band’s soul will be sold down the river when it comes time for the big payoff—signing the dotted line to a record contract. It’s the contract that provides monetary support and determines the direction of the artist, for the company is equipped to provide the promotional, management, and distributing apparatus, though not always as much as a recording act might desire.

Though Balcones Fault, in various incarnations, had been a fixture on Austin’s progressive country scene since 1972, it was not quite two years ago that the band’s masterminds, Jacobs and Clark, decided to exercise some self-determination. At that time, local music divided in two factions—country and everything else. Noting a surplus of cosmic cowboy musicians and seeing no competition elsewhere, the show band concept evolved. There were certainly plenty of listeners in Texas not particularly enamored of watching stone-faced figures whining about wide-open spaces and cow paddies. So anyone not wearing boots and over the age of eighteen was fair game in this plan to establish a base. Next, the Fault faced two options: work hard and hope and wait until a record company representative happened by, liked what he heard, and signed them up; or think like a record company and speed up the process. They decided to save the record companies the trouble. They discovered themselves.

For the plan’s operating capital, Jacobs and Clark combined traditional financial wisdom with show biz hustle and sold Balcones Fault to investors as a potentially profitable future commodity. Explained Jacobs, “Backing a band is like a lot of highly speculative investments. But the people that get into such things aren’t looking for safe investments. They could buy certificates of deposit if they wanted a safe investment. They’re looking to buy a baseball team, drill an oil well, or back a band. It’s a risky business.” By securing seed money in excess of a quarter of a million dollars (Jacobs refuses to say exactly how much: “Just say it’s as much as it costs to drill an oil well”) and establishing a two-year time schedule, Balcones in effect bought time to research the business and mature simultaneously, building towards recording an album by themselves and selling the finished product to a major label. They would enter the recording industry, in Jacobs’ terms, “more as subcontractors than as laborers.”

Money didn’t have to buy the band. That was already there. Don Elam joined the squad not long after the make-it-or-break-it decision. McGeary and the other drummer-vocalist Michael Christian were already pros, having worked in Michael Murphey’s and Jerry Jeff Walker’s bands. Riley Osbourne also signed on, bolstering the lineup as a proven keyboard player who had album experience with two other Austin groups, B. W. Stevenson and Greezy Wheels. Dean Stimulus, the bass player, had hacked around the nightclub cocktail lounge circuit long enough to know he wanted better.

As they worked toward the album, Balcones built up a touring circuit through Texas, playing at deb parties, political rallies, conventions, and even exploiting the tired progressive country clubs. To measure their recording talents they made a local single at Armadillo World Headquarters in 1975, then worked on a pre-album album last spring before journeying to the Record Plant in Sausalito, California, last July to put down an album for keeps. They paid $150 an hour for studio rental, and the month spent rehearsing, recording, and mixing in California was their most expensive lesson yet in How to Become Stars. When the experience was over they had transformed from the wacky show band from Texas into a high-caliber recording group. The result is Why Is the Band Laughing?

So what do they sound like on disc? Well, certainly smoother and more accomplished than what I’d heard from them onstage. Horns and piano have emerged as their musical signature. Elam and Kerry Kimbrough, the other horn man, come through with the sass and brass of a much larger Muscle Shoals-styled horn section. Osbourne turned out to be the musical spark that can activate an image and identity— something Balcones as a show band hasn’t yet entirely come to grips with. He contributed two selections and a raggy, good-time piano that fits snugly next to Elam’s arrangements of cocktail-jazzy instrumentals such as “Caravan” and “Watermelon Man.” Commercially, McGeary’s two soft reggae adaptations (as with any show band, it’s a passable sketch of the real thing) offer the most promise, with the album versions slowed down considerably from the stage act for easier disco access. The only survivors from the stage show of a year ago are “Leave Your Hat On,” the Randy Newman ode to clothes fetishists, packed with aural gimmickry, and “42nd Street,” replete with Spike Jones-inspired horns, bells, tap dancers, and train whistles.

The metamorphosis from regional to national profile, from live act to album makers included a few casualties. Some of the recording sessions resembled encounter therapy. The band had to learn how to maintain a consistent tempo. Christian was told he couldn’t sing. Their manager and producer were dismissed in the process in favor of ones with better judgment and more extensive business connections. The slapstick humor that riddles their live show was subdued and some hometown-pleasing elements of the act were dropped altogether. Thus, no Sons of the Pioneers whistling along with “Tumbling Tumbleweeds,” no polkas or romantic Spanish ballads. But for all the problems, Balcones Fault survived without a personnel shake-up.

Simply put, Jacobs believes, “We paid a lot of money to get the equivalent of a good-quality third album the first time around.” The preparation worked. Previous non-country bands in Texas have rarely been ready to make the broad leap from night spot gigs to the technical, complex atmosphere in which albums are made, Two of Austin’s most celebrated cases, Greezy Wheels and Shiva’s Headband, failed miserably in their first time in the studio because they were still geared to the informal setting of clubs, bars, and dives.

The only remaining barrier, if indeed Fault wants to hurdle it, is getting a major label to buy and distribute the record. Going that route can mean a high price tag, which can spell lots of browsers but no buyers. To avoid that, Jacobs claims he’s prepared to employ a not-so-radical plan of action—local distribution. Just as Huey Meaux and Major Bill Smith made their fortunes in the fifties and sixties operating out of Houston and Fort Worth, the Fault is prepared to distribute the album independently statewide by January, then lease it to a major label once regional sales prove national potential. “Record company executives are conservative men and women. We may have to prove it to them before they’ll take a chance,” Jacobs says.

These are the kind of odds that appeal to a gambler like Jacobs. His two-year plan, so far, is on schedule. “If we waited for a record company to come in and give us an advance and make the record, not only would I still be waiting to go into the studio, but I also wouldn’t have very much prospect of getting rich from it if we did happen to be an overnight sensation and surprise a bunch of people who don’t know anything about the Texas record market.”

The music industry revolves around New York, Los Angeles, and Nashville. Because Texas is out in the sticks in the opinion of the recording establishment, the state is seen at most as merely a breeding ground of raw talent. Usually if a band wants to break out of regional confines, they leave home for the three hot spots. By rolling the dice with a thick bankroll to back it up, Balcones Fault has brought the game a little closer to home.