In 1959, as the civil rights movement approached a new decade, John Howard Griffin, a white native of Dallas, embarked on what was then, and still seems now, a mad plan. With medical assistance, he darkened his skin—becoming, in the parlance of the day, a “Negro”—and then proceeded to journey through the Deep South to see what it was like to be black. When his travels were finished, he would share what he learned (things he probably already knew he would learn) with the rest of the world. Griffin recognized a central truth about his culture and time: whites would listen more closely to a white man telling stories of black life than they would to a black man telling the same stories.

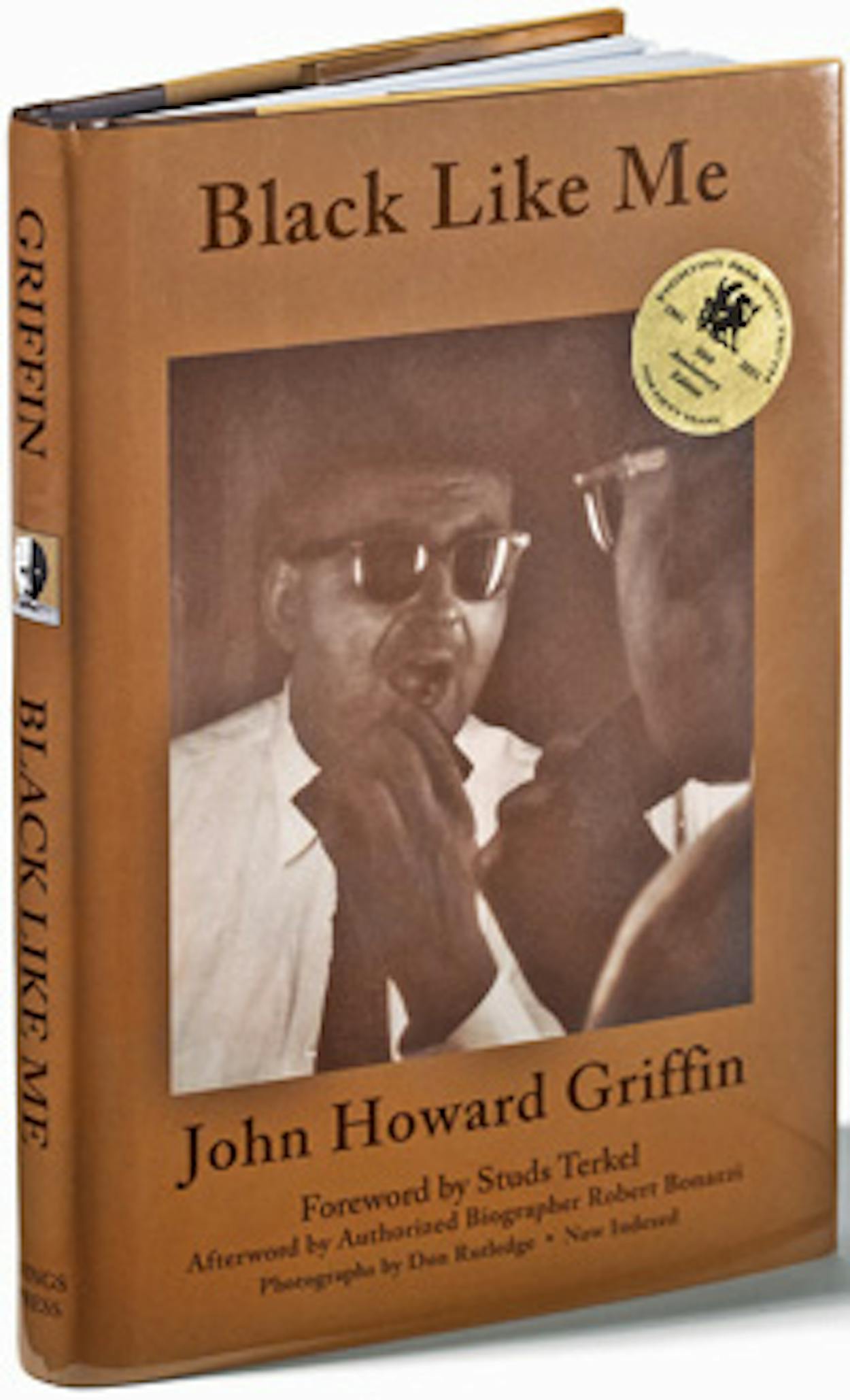

The result was the classic Black Like Me (Wings Press, $24.95), long a staple of high school social studies classes and now reissued in a fiftieth-anniversary edition. How does this mainstay of mid-twentieth-century liberalism hold up after all these years? It remains an extraordinary and brave book, whose strengths and flaws tell us much about our immediate racial past and, indeed, the present state of race relations. For me, a child of 1960’s East Texas, reading Griffin was like taking a bad trip down memory lane. The book expertly captures the claustrophobic feel of that world, where whites expected deference from blacks and blacks chafed at oppression but saw a glimmer of hope in the second American revolution that was just beginning. Much of what Griffin describes will be jaw-dropping to anyone born after, say, 1970, who will be amazed at the enormous amount of energy that was expended to keep white supremacy in place.

Griffin’s narrative makes plain that the legacy of slavery shaped the South well into the twentieth century. Most of the whites he wrote about as he made his way through Louisiana, Mississippi, Alabama, and Georgia seemed to regard blacks as lost property—property that their ancestors had once possessed, or that they might have obtained if the Civil War hadn’t occurred. Which posed a question: If blacks were no longer property, why were they still in the South? The answer, from the white perspective, was obvious—they were there to continue to work in homes, fields, sawmills, and other similar venues. They were also there to tamp down the class antagonisms that would arise if poor whites were suddenly placed at the rock bottom of Southern society and had no one to look down on. The black perspective on this question was very different; by the time of Griffin’s writing, most blacks who were determined to leave the South had already done so, during the great northern migration of the early twentieth century. Those who remained stayed because they couldn’t or didn’t want to leave; the South was their home. The tension between these conflicting visions is palpable throughout Black Like Me.

Griffin recounts story after story of petty cruelty and tyranny—the bus station attendant who finds Griffin’s mere presence intolerable and throws change at him when he asks her to break a $10 bill; the bus driver who closes the door each time Griffin tries to exit, until he gets tired of toying with his “black” passenger; the genteel, pipe-smoking man sitting in New Orleans’s famous Jackson Square who suggests that Griffin find “someplace else to rest,” even though there was no law preventing blacks from being in the park. All of these people, nearly a century after the Civil War, acted as if they were plantation masters and mistresses from days of yore.

And then, of course, there was sex. Griffin’s anecdotes reveal a white South obsessed with black sexuality. Motorists who pick him up as he hitchhikes ask lurid questions about his anatomy and speak lasciviously about black women, taking their conversations “to the depths of depravity.” Men inquire about his interest in white women and leave notes in restrooms seeking black women. These parts of the book probably provoked the most ire when Black Like Me appeared. Jim Crow, after all, was supposed to be about keeping the races separate. But from the earliest days of slavery and long after its abolition, white men crossed the color line to have sex with black women. The old habits never died out, but it was crucial to pretend otherwise.

Still, despite Griffin’s ability to see some things so clearly, he was, in many ways, a product of his upbringing and time. In an afterword written for this edition, Robert Bonazzi says Griffin questioned and transcended his own racism, but some of his prejudices show through. He often notes the cleanliness of the black establishments he frequented, as if this cleanliness was surprising. At other times, he describes blacks as sensual people, “sensuality” offering men an “escape, proof of manhood for people who could prove it no other way.” Well, perhaps they could not prove it to white people, but black men of the South had ways of being men in their own communities: going to work and taking care of their families, for instance, or acting as a deacon or minister in the church. Griffin shows no sign of being in touch with any of this, because his methodology didn’t allow him to really get to know the black community. And that is this book’s chief flaw.

By choosing to travel from place to place, never putting down roots in any community, Griffin effectively cut himself off from black life. Perhaps this was the only way his experiment could be conducted, but his status as a drifter skewed his vision of what it meant to be black. Blacks struggled in the South, but they usually struggled as members of families and communities, each of which served as a respite from the hostile world outside. Griffin misses that part of the story and, consequently, portrays being black as an unremitting nightmare.

Though Griffin presents himself as having lived as a “Negro,” he did not. He was a white man who had darkened his skin and lived for a time on the periphery of the black community. But it was never essential for him to cross that border; the critical thing, the really indispensable thing he did was to put himself in danger by allowing others to think he was black. There are moments during Black Like Me when, despite the fact that you know full well Griffin survived to tell his tale, you find yourself fearing for his life. One doesn’t want to exaggerate the hardships he endured: he experienced little more than a taste of the fear that was a constant companion to Southern black men and women for so many decades. But we can note the limitations of Griffin’s masquerade and still recognize its power. For many Americans, even a fraction of the truth was too much to bear.

Annette Gordon-Reed, a professor of law and history at Harvard University, was born in Livingston and raised in Conroe. She won the Pulitzer Prize in 2009 for her book The Hemingses of Monticello: An American Family.

What else we’re reading this month

Men In the Making, Bruce Machart (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, $24). Short stories about hardscrabble Texans from the author of the acclaimed The Wake of Forgiveness.

Sybil Exposed, Debbie Nathan (Free Press, $26). A Houston-born journalist’s exposé of the elaborate fraud behind the world-famous case of multiple personality disorder.

Unprecedented Power, Steven Fenberg (Texas A&M Press, $35). Biography of Jesse Jones, the Houston entrepreneur who helped save the country from the Great Depression.